I’m not an organized person by nature. However, I’m the kind of guy that likes to implement systems to overcome problems. In medical school, I didn’t have any sort of structure for my projects and found it frustrating to find the most recent versions of papers, posters, and other writings. Here’s an approach that I started using in fellowship that works for me.

Step 1: Save all of your work in one folder

This seems pretty obvious, but modern operating systems, cloud-based storage systems, and network drives all compete for your documents. If you are a windows user, I’m willing to bet that you have different projects saved on the Desktop, in your My Documents folder, in your cloud storage, and in your email in/outboxes. You probably also have alternate working drafts of your writings on different computers. This is a recipe for disaster.

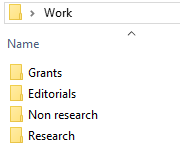

Instead, make one folder that is accessible from your usual workstation. Call it Work, or something more creative. Save freaking everything in your Work folder from now until the end of time.

Step 2: Make subfolders for different types of your work

Within your Work folder, make a subfolder for each flavor of project that you do. I have individual folders for Grants, Editorials, Non research (for blog posts and other miscellaneous work), and Research.

Step 3: Numerically and descriptively label each of your projects in its own sub-subfolder

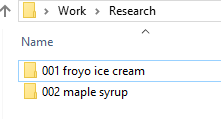

Let’s say you are about to have your first meeting for a new research project studying the effects of Fro-yo vs. ice cream on cholesterol among adults. All of the relevant documents for your next research project will now be saved in the 001 froyo ice cream folder, seen here:

(You also had a good idea for a maple syrup study that you have also started simultaneously.)

What is the threshold to start a new numerically and descriptively labeled sub-subfolder? Mine is pretty low. If I think I have at least a marginally good idea and have started emailing folks about it, I go ahead and start a new folder. A PDF copy of those initial emails are often the first things that I save in that new numerically and descriptively labeled sub-subfolder. (I loathe MS Outlook but have to use it. Its search is terrible. Saving copies of important emails saves me some headache.)

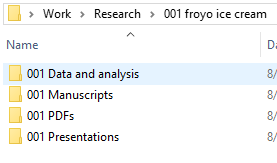

What kinds of things are you going to save into these folders? That’s up to you. I recommend saving your literature searches, copies of relevant important emails, research proposals, and so on. I like to make sub-sub-subfolders with headings like Data and analysis, Manuscripts, PDFs (for relevant literature saved from your library’s journal subscriptions), and Presentations. You should probably number these folders to match the overall sub-subfolder number as well.

Step 4: Name each item within your sub-sub-subfolders starting with the a) sub-subfolder name, b) a short descriptor of the thing you are writing, and c) ending with a revision and version number

Example: You finished all of your awesome dessert-related research and are starting to write up the main findings. You are going to start your first MS Word version of the first draft. I suggest naming it like this: “001 froyo ice cream main findings r00 v01.docx“.

Using version numbers

The r00 (that’s r zero zero) means that this particular draft has never undergone a major revision from a prior draft. The v01 (that’s v zero one) means that it’s the first version ever. You’ll email out a file titled:

001 froyo ice cream main findings r00 v01.docx

…to your primary collaborator who will send back something with edits, they’ll probably save it as:

001 froyo ice cream main findings r00 v01 BHO edits.docx

…which is nice but doesn’t help with your naming structure. Immediately save that to Work\Research\001 froyo ice cream\Manuscripts\ as version 02, or:

001 froyo ice cream main findings r00 v02.docx

Accept or refuse their edits and save that version as:

001 froyo ice cream main findings r00 v03.docx

…then send this out to more collaborators. You’ll wind up going through somewhere between 5-20 (or more) manuscript versions before you are ready to submit to a journal. What’s nice about this system is that you’ll have no problems figuring out which version of a file you are getting edits on. Remember, at >5 collaborators, the probability of one co-author checking their email <1 time per month approaches 100%. You'll be working on the 10th version of your draft and receive an email from the slow reviewer with edits to version 03. Sticking to this scheme helps you figure out how to integrate their suggestions into the current version by tracking the intermediate changes.

Note: I suggest using two digits (v01-v99) for the revision and version numbers rather than starting with 1 digit (v1-v99). This helps keeping files in alphabetical-numerical order when sorting in your file explorer. Computers aren’t smart enough to figure out that v12 doesn’t come between v1 and v2.

Using revision numbers

For some reason, the New England Journal of Medicine doesn’t accept your manuscript for publication after sending it out for review. Lucky for you, it was sent out for review and the reviewers gave you some high-quality feedback that will improve your paper. Now it’s time to start revision 01! When prepping it for the inevitable JAMA submission, you’ll be working starting on revision 01 and version 01, or:

001 froyo ice cream main findings r01 v01.docx

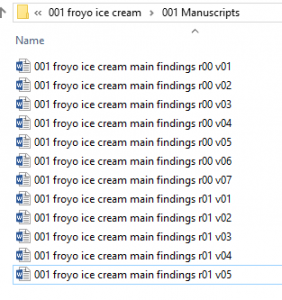

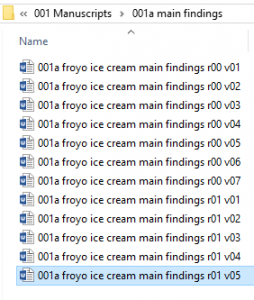

In the end, you’ll have a folder looking like this:

Look at how pristine and well-organized this is!

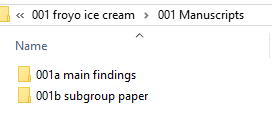

Step 4.5: Use trailing letters for projects with multiple publications

Let’s say that you decide to write both a main findings manuscript and a subgroup analysis manuscript. How to stay organized? Just the 001 Manuscripts folder into two sub-sub-sub subfolders for each publication, with 001a for the main findings and 001b for the subgroup analysis. It’ll look like this:

The naming scheme changes slightly as filenames will start with 001a instead of 001, like this:

Step 5: For the love of all things decent, regularly back up your Work folder!!

I can’t stress this enough. Keeping your Work folder in a commercial cloud storage drive doesn’t count as backing things up. Dropbox only saves things for 30 days in their basic plan. If you aren’t actively backing up your data, you can safely assume it isn’t backed up. One dead hard drive in a non-backed up folder can mean months or years of lost work.

Remember to check your institution’s policies for determining your backup method of choice. If you are working with PHI, saving it on an unencrypted thumb drive on your keychain won’t cut it. If it’s okay with your data policies, I recommend buying a DVD-R spindle or a bunch of cheap thumb drives and setting a calendar date to write your Work folder to a different DVD-R or different thumb drive once per month (i.e., you should have this on a different thumb drive each month). Keep these in a locked, secured, fireproof area that is consistent with the policies of your organization. Better yet, keep them in multiple locked, secured, fireproof areas if possible. For bonus points, get an M-Disc DVD discs and compatible burner, which should be stable for >1,000 years, unlike the usual 10-20 years of conventional burnable DVD-Rs and CD-Rs.

Or, just speak with your friendly neighborhood IT professional about how your institution recommends backing up the data you are working with. Chances are that they have a server that they back up 3 times per day that you can just use for a modest price. It’ll be worth the sorrow of lost data and drafts.