There have been a lot of mixed messages when it comes to the state of child mental health and the amount of psychiatric treatment children are receiving. On the one hand, we hear the alarm sounded by many that too many children without significant mental illness are being diagnosed and prescribed medication. On the other hand, we hear that psychiatric care is too hard to get and that the major problem continues to be underidentification and undertreatment.

Is there some truth to all these claims? A new study from the New England Journal of Medicine tries to sort out some of these questions. The study followed over 50,000 youth, looking at different time periods over the past 2 decades: 1996-1998, 2003-2005, and 2010-2012. The primary variable of interest was how many children between the ages of 6 and 17 received some kind of mental health care and whether any increases were disproportionately from those children with more severely impairing illness versus those little or no impairment from their behaviors.

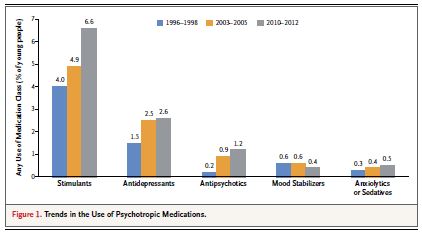

The results of this study are quite interesting and some were unexpected. Perhaps the broadest finding was that more youth are getting mental health treatment now (13.3%) than in the mid 1990s (9.2%). That part is probably not too surprising, and these increases occurred among the group with more impairing illness and among the group with less impairment. Further, increases were found both in the rates of psychotherapy and for most classes of medications, as shown in the figure. The smaller group with more impairing disorders had the largest relative increase in service utilization but, since that group is smaller, those will less severe symptoms had a larger increase in mental health treatment rates in absolute terms.

It is worth noting, however, that even among youth with more severe impairment, the rate of receiving any mental health care was less than half (43.9%).

The finding that the authors admitted was quite unexpected was this: the overall percentage of youth who have more impairing mental illness actually dropped during this period of increased treatment (from 12.8% to 10.7%). Yet while it may be tempting to think that the increase in treatment may be partially the cause of the decrease in impairing mental illness, the study cannot demonstrate causation.

The study has picked up its fair share of publicity, including an article in the New York Times. One interesting development is that many media outlets are featuring the drop in number of youth with more impairing mental disorders as the primary statistic of interest, despite the fact that this finding was neither a part of the study’s title nor its abstract.

As you can see from these complex results, there is something in this study for everyone to point to on either side of the “psychiatry debate.” Some will choose to highlight the increase medication usage, some the continued lack of services for severely impaired youth, and some the possible decrease in overall levels of impairing psychopathology…..and they are. For more moderate voices not inclined to just cherry pick the results that fit our worldview, the picture indeed looks complicated but perhaps not that shocking overall. Yes there kids out there who are suffering because of a lack of treatment, and yes there are many kids getting medications they may not need. We simply need to work on both parts of this equation.

Reference

Olfson M, et al. Trends in Mental Health Care among Children and Adolescents. NEJM. Epub May 21, 2015.