Suicide and suicide attempts remain a major public health problem. There is now evidence that after years of decline, suicidal behavior is once again on the rise. In Vermont, suicide is now the number two killer of older adolescents. One can only imagine the attention and public health response that would occur if something like measles or ebola or terrorism was related to this kind of mortality here in Vermont and elsewhere. A recent compelling story on the subject was aired last week on WCAX by Darren Perron entitled Hidden Heartbreak Part 1 and Part 2.

While there have been many initiatives taken to try and prevent suicidal behavior, it has remained a challenge to demonstrate that these efforts are effective, especially when it comes to decreasing discrete behaviors such as suicide attempts. Since these are (thankfully) relatively rare events, very large sample sizes are needed to show the effect of an intervention. A recent study, however, attempted to do just that by comparing the efficacy of three different programs in a sample that included over 11,000 adolescents from 168 different schools across 10 EU countries. The paper was published in the prestigious journal, the Lancet.

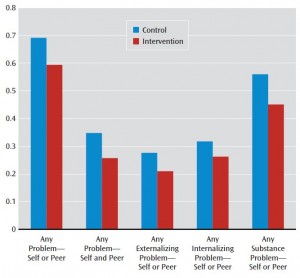

The schools were randomized to administer one of three intervention programs. The first, called Question, Persuade, and Refer focused on training teachers to identify and communicate with high risk youth. The second program, Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM), was a universal intervention designed to teach all students to change negative perceptions and to enhance coping strategies through lectures, workshops, and educational materials. The third program, Screening by Professionals, involved examining the study’s baseline mental health data and inviting those students who scored above established cutoffs to get a professional assessment. There were also control schools that received educational posters only. The primary outcome measure was number of new suicide attempts and presence of severe suicidal ideation at 3 and 12-month follow-up, as assessed through self-report instruments.

At the three month follow-up, there were no significant differences between any of the intervention groups and the control condition. However, at 12 month follow-up, students who received the Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM) program had about half (0.70% versus 1.51%) as many suicide attempts compared to the control group and were half as likely to report serious suicidal ideation. Putting the results another way, having 167 students in the program was found to be related to 1 less suicide attempt. These results did not vary according to sex or age, and there were no completed suicides that occurred during the study period.

The authors concluded that the Youth Aware of Mental Health program is effective in reducing the number of suicide attempts. They urged more study and broader implementation of universal suicide prevention programs.

What makes this study exciting is that it is one of the first to document actual reductions in suicide attempt related to a school based intervention, as many studies prior to this have focused on increases in education and attitudes. The YAM program does have a website for people interested in training and implementation of their method. Doing a little research with help from the Vermont Youth Prevention group, it looks as though many Vermont schools utilize a program called Lifelines that has both primary and secondary prevention components. This program, from a quick look, appears to have some overlap with the YAM program, although a more thorough review and comparison might be useful.

Reference

Wasserman D, et al. School-based suicide prevention programmes: the SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2015: epub ahead of print.