Here is the link to the list of objects on the Spiritist Altar:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/14QTnUPHVeIzAHiQMNxY_rDkH-63LXXEzwjV20oXqasw/edit

Here is the link to the list of objects on the Spiritist Altar:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/14QTnUPHVeIzAHiQMNxY_rDkH-63LXXEzwjV20oXqasw/edit

Here is the link to the google document used to analyze the objects.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1nd7KHlFCZoTueygON_vsT3zpk9kRTnmrVuRNCguhcYQ/edit?usp=sharing

My apologies for the previous faulty link

Walking into the Fleming Museum’s Spirited Things: Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic Exhibit, your eyes are inundated by radiant, intriguing, and esoteric objects of various Afro-Atlantic Religions. There are altars composed to honor various deities, plethoras of shining garments, beaded dolls, colorfully wrapped bottles, gorgeous tapestries with images of deities and mythical beings, gathered to express religious cultures. Families of objects line the walls and floors all telling a story of religious and cultural diversity of Yoruba Religions, Brazilian Candomblé, Santería, Haitian Vodoun, and much more.

To the left of me, in a large glass case surrounded by bottles of rum, cowrie shells, and dolls for wealth and prosperity, lies a strange wand-like object. This object, by reading the tag underneath, is known as the Ibirí Wand of the Goddess Naña. By observation, this object is about 15-20 inches in length, and extends from a straight handle, into two pieces of straw that bend in opposite directions to create an oval shaped looped at the summit of the wand. The ibirí is made of Palha da Costa, or African straw, and is adorned with rows of blue, red, gold and white glass beads. Glass Beads, or any links of beads are said to, within the practice of Candomblé, after being washed in herbal baths or blood offerings, are said to take on the ashe of the deities they are used for, and become a connection or a literal “link” from user or practitioner to the divine. Along with the beads decorating the Ibirí, pearly white cowrie shells, which create an oceanic aspect of the wand, entrancing sections of leather ranging in color, drawing your eyes in all directions around the shape of the wand, are present. Beginning at the base of the handle, my eyes seemed to follow the colors as they changed starting with black, blue, green, yellow, white, and finishing with red. I had never seen an object quite like this, that could catch my eyes and draw them in so many different directions at once, I was eager to discover more about this mesmerizing entity of an object. In this essay, I will provide background information on both the Ibirí and its owner, Naña Buruku. Also, my main question for this essay is how is the Ibirí wand is used, by practitioners of Naña Buruku, within ritualistic practices? Also, I wished to introduce the history of Candomblé, and beliefs within this religion. I also will expand the concept of the spiritual importance that religious objects have. As religious objects can also possess a similar spiritual value as the owner of it, looking past its mundane origin. I will be relating this concept to one of our past readings, “A Sorcerer’s bottle” by Elizabeth McAlister.

To begin, Candomblé, a word who’s meaning “dance in honor of the gods” is “a religion is a mixture of traditional Yoruba, Fon and Bantu beliefs which originated from different regions in Africa. These beliefs were transported within the hearts and souls of slaves during the slave trade. It has also incorporated some aspects of the catholic faith over time. These people, along with their indigenous religious beliefs and practices, were essentially stolen from Africa, and were transported to Brazil. Candomblé, is a hybrid, or a “syncretic” religious mixture of Traditional Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu religious beliefs, all origination from different regions of Africa. Music and Dance are the one of the primarily important aspects of Candomblé, within ceremonies, mainly. Practitioners of Candomblé, believe in one all powerful god, called Oludumaré. He is served by lesser deities called Orishas, whom one of which in Nana Buruku.

Continuing along the introduction of the orisha, I would like to share a bit of history regarding Naña Buruku. She is again, an orisha, or a lesser deity within the Brazilian religious practice of Candomblé. She is considered the Orisha of Death, Dance, Healing, Disease or Pestilence, and other aspects as well. She is considered a “grandmother” of the Orisha’s and is seen very much as a wise-woman within Candomblé. Two of her children, are Ogun, the orisha of metal or iron, and Obaluaiye, the orisha of smallpox and pestilence. Naña is known amongst practitioners of Candomblé, as a powerful deity for asking for a pregnancy, to terminate a pregnancy, and for various types of healing. She is said to use a similar Ibirí wand to my object in the Fleming Museum, as a broom of sorts, or as a staff to guide her followers and her children to their highest potential, like a grandmother spirit would do. However, just as Naña Buruku uses the Ibirí as a tool for helping her children, grandchildren, and devotees, the Orisha’s tool has also been known as a weapon. With this malicious usage of the Ibirí, or the ileeshin, an alternative Yoruba word for the Ibirí reflects a side of the Grandmother spirit that is rather contradicting and darker. “But if a cruel and horrible person stands before her, she can take the ileeshin, thrust it out horizontally before her and strike its looped tip against the belly of the man” (Thompson 1983, 71). This aspect of the Ibirí suggests an aspect of the Orisha that is just, and seeks to have justice against cruel or unjust people. This tells a sort of duality to Naña Buruku, a balance between nurturing and healing with justice and dealing punishment to those who may deserve it. The Ibirí and Naña both share a very balanced and equal power, dealing with both aspects of the world; that which is cruel and unjust, and that which is healing and has justice. The colors of blue, gold, white and green emphasize the healing and nurturing side of the Orisha, and her desire to watch and guide over her children, grandchildren, and worshippers. After feeling like I needed to understand the Orisha on a more personal and human level, I wished to learn more about the backstory of both the Ibirí and the Orisha, during her human experience.

The Ibirí wand, was said to have been born with Naña Buruku at the beginning of her life on Earth. “Nana has possessed a certain staff from the beginning of her life on earth. She was born with this staff; it was not given to her by anyone… when she was born the staff was embedded in the placenta” (Thompson 1983, 71). This expresses that the history of Naña Buruku and the Ibirí are intertwined and show the dependence both the object and the deity have on each other. The Ibirí, was also said to have been cut from the placenta after birth, and placed into the Earth. The Ibirí was then said to grow as the child grew. “ Then they cut it from the placenta and they put it inside the Earth. But surprisingly, as the infant grew, the staff grew, too” (Thompson 1983, 71). This legend, in a sense emphasizes how Naña Buruku’s áshe, or her divine powers, grew as she did within the Ibirí and also emphasizes the idea within Afro-Atlantic religions that one’s áshe, or divine influence, grows along with them in the world. Moving away from the history of the object itself, into another point of my essay which is how the reflection of Naña Buruku’s ashe, can be seen and acknowledged within the the ibiri, as a vessel of spiritual energy. This connection of energy can be found again, within “A Sorcerer’s Botle” by Elizabeth Mcallister, a past. reading of ours.

Within “A Sorcerer’s Bottle” McAllister discussed how she discovered through a special bottle made for her by a Religious Sorcerer, that were existed so much more beyond the materiality of the object. This reading reminded me of the Ibirí, as the wand seemed to also have a spiritual “mind of it’s own” as well the bottle. The Ibirí was used as a weapon to harm other people at one point. This fact, along with how the wand seemed to grow simultaneously with Nana Buruku, told me that wand had the similar energy as the bottle in the reading. McAllister describes the object as a piece of art, along with a magical entity, as well. “ The bottle was thus commissioned; I thought of it as my first piece of art. Or was it? Right before he gave it to me, the bòkò turned it into a work of magic, a wanga” (McAllister 1995, 305). This quote enforces my idea and additional point of this essay, of the equalized reflection of spiritual value inside an object, to the owner of it. The Ibirí’s power, and its connection to Naña Buruku, showed me the value far beyond the object that sat in front of me in the museum, I related to it’s history and envisioned it’s power and it’s comparison to Naña Buruku. Shifting again from discussing the orisha, to discussing her Ibirí. I’d like to expand more on just what the Ibirí is, it’s ritualistic and spiritual purposes within rituals, etc.

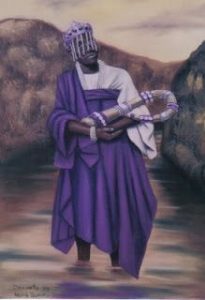

The Ibirí, along with being used by the Orisha herself as a broom, as a staff of guidance, as a weapon, etc. is seen heavily in Candomblé imagery in the crook of Naña Buruku’s arms, as she is swaddling it like a child, again emphasizing her role as a grandmother spirit, a nurturer, and a healer. In one of my research questions, I wanted to discover more about the modern use of the Ibirí within ritualistic practices. This leaded me to discover that worshippers and devotees of Naña Buruku use a form of dancing called Tidalectics, a style of dancing that includes a swaying motion parallel to the action of the oceans waves. Tidalectics, is seldom seen within any other ritual besides one simply worshipping Naña Buruku alone. The Tidalectics style of dancing creates connection to the nature of the Orisha herself, as she has been said to be found near oceans, rivers, and streams. I did not, interestingly, discover much about the use of the object itself during rituals. However, it is still used outside of rituals, as a vessel for the stories of itself and Naña Buruku. After discovering Tidalectics, and it’s connection to the orisha, I began to search for more possible connections to the ocean. I discovered through more research about oceanic connections to the Ibirí and Naña, about Cowrie Shells. These are white, pearly shells, which are naturally used as a representation of water, or of the ocean. The Cowrie shells used to embellish the Ibirí create a further connection between the orisha and to the ocean. The Tidalectics style of dancing also resembled the sweeping motion of a broom, which Naña was said to perform using the Ibirí, to sweep away pestilence and disease. In the practice of Initiation into the practice of Naña Buruku, practitioners will wear long dresses, usually of the color blue or gold, and take corners of their dresses, and sway them back and forth, mimicking the action of sweeping a broom.

After discovering the existence of such an object, my mind has been objected to make many connections between a material object and the nature and personality of an incredibly wise and powerful deity. The Ibirí has allowed me to perceive the nature of an object far beyond just what materials, colors, and embellishments meet the eye. The Ibirí wand also allowed me to discover the existence of a foreign style of dancing I had never encountered before, and can be used to honor a deity who’s uniqueness and respectability is as diverse and eclectic as the object that she has carried since birth. The practice of Candomblé is one that can be perceived as radiant, diverse, and honorable as embodied in Naña Buruku. The Ibirí wand is an object that’s personality and backstory have transcended time itself and continues to live on in antiquity within the walls of the Fleming Museum, waiting their every day to meet all who are lucky to see it, and to teach them about itself and the history of a truly wise grandmother orisha.

Below are photo’s of both the wand itself on the Fleming Museum website on the exhibition and an Illustration of Naña Buruku paired naturally with the Ibirí found via Internet.

Bibliography:

McAlister, Elizabeth. “A Sorcerer’s Bottle .” https://bb.uvm.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-2315560-dt-content-rid-10925763_1/courses/201709-95021/rel298.mcallister.pdf.

Sansi, Roger. “4.” Fetishes and Monuments: Afro-Brazilian Art and Culture in the Twentieth Century, Berghahn, 2010.

Roger Roca-Sansi: Fetishes and Monuments: Afro Brazilian Art and

Griffith, Paul A. “Chapter 4 .” Art and Ritual in the Black Diaspora: Archetypes of Transition, Lexington Books, 2017.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Chapter 1: Black Saints Go Marching in .” Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, Random House, 1983, pp. 68–72.

When I walked into the museum after being told about our project I already knew that I wanted to pick something on the Haitian Vodou altar. There is something about Vodou that has always intrigued me. Maybe it was its misrepresentation in media that made me want to learn more about it, just like with my interests in Paganism and Wicca. That morning I walked into the exhibit and over to the Vodou altar I noticed objects and details that I had not noticed when we had previously visited. I was drawn to multiple objects that had feathers on them, objects that my prior knowledge of African diasporic religions could not help me understand. There was one specific object with blue and red feathers and an orb and stem kind of shape that caught my attention. Looking through the booklet next to the altar I found the object and read about it. It was a pakèt kongo for the goddess Èzili Dantò, protector of single mothers and abused women. At that point I did not need to look at any other objects, I knew I wanted to research Èzili Dantò and the pakèt kongo.

A pakèt kongo is a kind of container. The one I chose is primarily red and blue and is completely made of fabric, except for the feathers. It sits elevated on the altar, the blue and red striped base is full and held with a blue ribbon tied in a bow. Ribbons come out from the middle of the base, pale yellow and sticking up like bubbles on top of a drink. As my eyes move farther from the center, gold ribbons with a green pattern of flowers and squares and red ribbons embroidered with blue flowers and stems and gold trimming curl outwards giving the rounded base the appearance of a blooming flower. Protruding upward from the pale yellow ribbons is a stem wrapped tightly in red fabric. Two feathers extend from the stem, wispy and bent. The large red one grabs my attention first, but the smaller blue one demands to be seen too. An intricate kind of calm intensity surrounds the object, which was at first confusing but as I learned more about Èzili Dantò and about how pakèt kongo’s work, I began to understand its meaning, how it is used in Vodou, and how it represents Èzili Dantò.

The pakèt kongo is a power object in Haitian Vodou. As I will talk more about later in this paper, pakèt kongos have soil from a graveyard or cemetery in them. This, along with what god or goddess the object is for gives it power. This one for Èzili Dantò is intricate. Èzili Dantò herself is an incredibly powerful Petwo goddess. It is not just her status as a goddess that gives her power, it is the fact that she is a woman and a protector, the fact that she is a warrior mother, that gives her as much power as she has. Her emotions are charged and intense, just like the pakèt kongo. Spiritual, emotional, and physical power all come together in the pakèt kongo for Èzili Dantò. It is interesting to see this object in a museum, especially an art museum. The pakèt kongo is not just art, there is energy in it that does not quite fit into a museum setting. In this essay I will talk about the ways in which Èzili Dantò’s power is represented in the pakèt kongo and how spiritual, emotional, and physical power all come together to make this object what it is.

Many African diasporic religions have the belief that when someone is sick or injured the problem is not just physical; it is also spiritual. It is usually thought that the problem occurred because whoever is sick or injured has fallen out of sync with the universe. The problem is then addressed ritually and holistically. In Haitian Vodou practitioners see doctors when needed, like for broken bones or serious illnesses, but the issue is still taken care of through ritual healing ceremonies in order to restore balance to the spiritual side of things. Most, if not all, of these rituals involve pakèt kongos.

The ancestor of the pakèt kongo is the nkisi, a healing bundle that comes from Kongo in Central Africa. There are minkisi (plural of nkisi) that have a kind of stem-on-globe shape, and then there are minkisi figurines. Both have medicinal herbs inside them, but the shape that has persisted through Haitian Vodou is the stem-on-globe shape (Thompson, 1983, 119-127) (Daniels, 2010, 418-423). Minkisi had many different uses and were often associated with spirits, much like Haitian pakèt kongos. However, pakèt kongos are not filled with herbs or medicines, the bases of them are filled with soil from a graveyard or cemetery. They are “charged with spirits from underneath the land of the living” (Daniels, 2013, 423). This core component is essential for the pakèt kongo to work at all.

The slaves that were in Haiti back in the late 1700s and early 1800s mainly came from Kongo and Benin. The slave revolution lasted from 1791 until 1804 and the slaves were aided by Polish troops that came with the French troops. Due to this Haitian Vodou was exposed to Catholicism and Èzili Dantò was paralleled with Our Lady of Czestochowa, the black Madonna. This exposure to Catholicism and the different aspects of Haitian Vodou that are still mixed with Catholicism add to the idea of syncretism. The word syncretism is generally used to “describe the process of conversions to Christianity…” (Johnson, 2016, 760). In Haitian Vodou many gods or goddesses have Catholic or Christian counterparts. The three Èzilis all have counterparts related to the Virgin Mary. Èzili Freda, known for her beauty is related to Our Lady of Sorrows, Lasyrenn, both a mermaid and a whale, is elusive. Lasyrenn’s counterpart is Our Lady of Charity, and Èzili Dantò, whose counterpart, as I said before, is Our Lady of Czestochowa. (McCarthy Brown, 2010, 221). However, the mixture of Vodou and Catholicism doesn’t end there. Many practitioners of Vodou attend Mass and go on pilgrimages to various churches. Attendance at Mass is incorporated into many complex Vodou rituals.

Women in rural parts of Haiti have very little power, however in areas that have changed more, like cities and urban areas, “at least half of the [urban] Vodou leaders are women” (McCarthy Brown, 2010, 221). Misogyny is a large part of Haitian culture, but Vodou empowers women. Èzili Dantò is important in Vodou because she gives power and protection to the women who need it most. Domestic violence is rampant in Haiti, and Èzili Dantò is the protector of abused women, through worship of her she gives women power.

Èzili Dantò is the fierce mother who will drop everything to protect her children, and she fought alongside the slaves during the revolution. She has two vertical scars on one of her cheeks, scars from an injury she received while fighting alongside her children. However, her children also betrayed her during the revolution because they thought that she could not keep their secrets. This belief caused them to cut out her tongue so she could no longer talk. It is said that Èzili Dantò cannot see blood because “At the sight of blood, Dantò goes wild” (McCarthy Brown, 2010, 231). One point that is emphasized in texts about Èzili Dantò is that above all else, she is a mother and her children come first.

In Karen McCarthy Brown’s novel Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn, there is a story told by Mama Lola’s daughter, Maggie, about an experience she had with Èzili Dantò shortly after arriving in the U.S. Maggie got sick and had to go to the emergency room and the physician there thought she had tuberculosis and wanted to hospitalize her, but Maggie begged to go home. The doctor let her go home under the condition that she come back the next day for more tests. However that night:

We just went to bed, and then I saw, like a shadow, coming to the light… Next minute, I actually saw a lady standing in front of me… with a blue dress, and she have a veil covering her head and her face… she pull up the veil and I could see it was her with the two mark. Èzili Dantò with the two mark on her cheek… she told me to turn my back around, she was going to heal me… She rubbed my lungs and everything; she rub it, and then she said, ‘Now you know what to do for me. Just light up a candle and thank me.’… I went back to the doctor, and the doctor say, ‘What’s wrong with you? I thought you was sick!’ (McCarthy Brown, 2010, 227)

Èzili Dantò drops everything when her children are in need, without thinking twice. However, there is another side to Èzili Dantò that I mentioned briefly before. She is also known as Èzili of the Red Eyes and “some people call Dantò a baka (evil spirit)” because “Dantò can be evil, too… She kills a lot. If you put her upside down, you tell her to go and get somebody, she will go and get that person. If that person do not want to come, she break that person neck and bring that person to you” (McCarthy Brown, 2010, 231-232). She is the warrior mother, the protector of single mothers, working women, abused women, and all her children. If she needs to be fierce, or if someone wants her to be evil, she will be.

The bright red on the base of the pakèt kongo and the large red feather extending from the stem speak to Èzili Dantò’s ability to change emotions in a heartbeat and to go from a caring mother to an intense warrior when needed. The colors are used to attract Èzili Dantò during rituals and the feathers are used to alert her of her commitment to help her children and aid in rituals. Feathers are a staple of pakèt kongos, “they are positioned from the head toward the floor, representing the movement of the vibrations of the cosmos to nature” (Daniels, 2013, 422). The bend of the feathers is symbolic, and not just something that happened because they are feathers and bend easily. They could be made to point straight up, however they are bent toward the floor because of the meaning behind it.

The calm and intensity in Èzili Dantò’s personality are shown in her pakèt kongo through the blue and red colors that are present. The blue ribbon tied in a bow around the base is secured with pins, and the binding of the fabric is not just to keep the soil from getting out but “also to ensure that the spirit is kept in” (Daniels, 2013, 423). As I mentioned before, there is a belief in Haitian Vodou that an illness or injury needs to be addressed both physically and spiritually. Pakèt kongos are used to help correct the imbalances in the cosmos through healing rituals. The one for Èzili Dantò is most likely used to pray specifically to Èzili Dantò for spiritual healing.

At the beginning of this project I wanted to learn more about Èzili Dantò just because of what I read about her in the little booklet next to the Haitian Vodou altar. That evolved into me wanting to know more about how the pakèt kongo on the altar represents her and how pakèt kongos are used in Vodou. I think I would need to see one used in a ritual to fully understand the ways in which they are used in Vodou, however it is one of the most interesting objects I have ever studied. Haitian Vodou combines art with ritual and the pakèt kongo is a perfect example of that. The object appears incredibly decorative, but it does have a purpose, and one that is incredibly important. Seeing the object on an altar in a museum puts it out of context, automatically making it more difficult to understand the use of the object, it seems more decorative than purposeful. Art has power, and the exhibit gives that a new meaning, making it fitting that a pakèt kongo for Èzili Dantò be on the Haitian Vodou altar.

Bibliography

Daniels, Kyrah Malika. “The Undressing of Two Sacred Healing Bundles: Curative Arts in the Black Atlantic in Haiti and Ancient Kongo.”Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 3(2013):416-429.

McCarthy Brown, Karen. “Ezili.” In Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn, 219-58. University of California Press, 2010.

McCarthy Brown, Karen. “Afro-Caribbean Spirituality: A Haitian Case Study.” In Vodou in Haitian Life and Culture: Invisible Powers, 1-25.

Thompson, Robert Farris. 1983. “The Sign of the Four Moments of the Sun.” In The Flash of the Spirit, 119-127. Random House, Inc.

Johnson, Paul Christopher. 2016. “Syncretism and Hybridization.” in The Oxford Journal of The Study of Religion, 754-771. Oxford University Press, 2016.

The staff (paxoro) for the God Oxalufa is my object of interest for this analysis. The uniqueness of this object was very compelling to my eye. I walked around the museum, and my eyes and mind stumbled upon a high staff surrounded by various crowns. Mounted on a block, standing about 5 feet tall stood this particular all silver staff. At the top of the staff is a silver crown with a single standing dove up on top. Hanging out of the mouth of the dove is a silver pendant of a bell. Pendants fall from the bottom of the crown in symbols of bells, mortars, fish, butterflies, and feathers. Approximately halfway from the top of the staff down to the middle of the staff are six equally placed tier-like structures. Starting from the topmost tier, slightly under the crown and then going down, each tier progressively gets larger. Identical to the crown mounted at the top of the staff, each of the tiers has the same pendants hanging from them. Each pendant represents an Orisha or God of the Candomblé religion. Visually analyzing this object lead to my curiosity about the use of this object and the symbolism this piece provides the individual who uses it in the Candomblé religion. Through research of the God associated with this staff, I was able to figure out the meaning and its interpretation to those who are in possession of the staff.

The religion this object is associated with is the religion of Candomblé, an Afro-Brazilian religion. Candomblé was founded in the late eighteenth century around Bahia. The elements in Candomblé resemble aspects of Yoruba religion. This decent of Candomblé from Yoruba was due to the prominent practice of the Yoruba religion among slaves. Candomblé focuses on the traditional dispensing of sacraments to the orixas or spirits or deities. Specifically, this object is for the orixa Oxalufa also known as Oxalá or Obatala.

This staff is meant to be a symbol of higher power and higher authority. It’s relation to the God Oxalá gives those in possession of the staff the view that they are a superior and are a follower of Oxalá. The staff is a symbol of power and the mixture of this and the association with the supreme God gives the staff the symbolism of royal power or authority power. The dove at the top of the staff symbolizes that purity of Oxalá. The dove is also the preferred sacrificial animal to give to Oxalá. This purity and power are shown through the staff with its numerous pendants. Each pendant has an association with another orixa or God in the Candomblé religion. For example, the pendant of the fish represents the goddess of the sea Iemanja, and the butterfly represents the goddess Iansa. Oxalá is the father or the senior brother to each other orixas. Therefore, their involvement in the staff dedicated to Oxalá symbolizes his authority to all kinds, Gods, and humankind. The style and presentation of this staff are essential, “Purity of sculptural presentation; symmetry; balance: these qualities can memorably imply iwa. Iwa also means custom, the traditional ways of life” (Thomson 1983, 11). This staff respectfully implies iwa, its carefully crafted pendants and balance of the tiers reflects a simple and traditional style of art. This finely crafted object is seen to be a symbol of authority and purity given explicitly to the highest elder in charge.

The orixa Oxalá is known in the Candomblé religion as the father of all Gods and the creator of humankind. He is known as the high God or the supreme God and is also the seniority figure. This position was gained by his high moral standards and the integrity of his priests and worshipers. Oxalá is visualized as the oldest of the orixas and walks with the staff to support his hunched over body. Each aspect of this staff is meant to represent Oxalá himself, “The orisha, or deities, in the Yoruba pantheon, distinguish themselves in altars by their colors, food, banners, and icons” (Thompson 1995, 51). In respect to his staff, silver is known to be one of his colors and white is also related to him. These two colors are represented by Oxalá because they are seen to be the simplest and purest colors. Seniority, purity, and whiteness are all used to describe him. White clothing is broadly associated with Candomblé but is more specifically worn by Oxalá worshipers. In the Candomblé religion the festival of Bonfim is a large gathering of people to celebrate the God Bonfim, “Bonfim had come to be identified with Oxalá, old king of all the Orixas; his colour is white, and he descended from heaven so that the intensively bright hill of Bonfim was his ‘natural site’” (ROCA, ROGER SANSI 2005, 184). This festival, though dedicated to Bonfim, is closely associated with Oxalá himself. The white color is suggestive of both Gods.

Specifically, leaders like Magalhães represents Oxalá in this particular festival, “Magalhães is the single most powerful political figure in Bahia and has been present at Bonfim since his periods in office as mayor of the city in the early 1970s. Despite his advancing years, Magalhães dressed in white, wore the necklaces of Oxalá and led the procession with a remarkable vitality. Often referred to by his initials ACM, or simply as ‘Cabeça Branca’ (‘white head’), Magalhães is strongly linked to Candomble and is a ‘son’ of Oxalá” (ROCA, ROGER SANSI 2005, 189). ACM participates in this festival by dressing in all white and bringing vessels of water to the house of Oxalá. Though the staff may not be present during this festival, the staff is representative of the power of the highest power and their purity and authority.

In an altar created by Mai Jocelinha in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, two staffs of Oxalá are placed on either side of a white draped cloth making it look like Oxalá as the center with the crown on his head (Thompson 1995, 51). In front are white and silver offerings including bells, white flowers, metals and ceramic tiles. This altar is meant to convey Oxalás glory, honesty, and purity. The staffs on either side of the altar are to signify the maturity and wisdom of the eldest figures. Their presence in this altar, especially their placement next to the God-like figure made out of the cloths represent their use as an object portraying royalty and power.

The representation of authority and seniority are given off by the staff of Oxalá. All figures in possession of this staff are not questioned to have high power in their community. Usually, these characters are the eldest authority or priests who are in possession of this staff. The pendants that hang from each of the tiers are heard to make the noise associated with Oxalá. Metals striking against each other is the sound of Oxalá walking with the staff to support him. Staffs are a royalty symbol, and in the Candomblé religion, this particular staff is seen similarly as a way to identify a person of higher power.

My initial thoughts about researching this object were about the use of this staff in particular festivals or rituals for Oxalá. A lot of my research was centered on Oxalá himself to find the significance of the staff. The staff itself I see is not very significant in the way that it is used but more in its symbolism for those in possession. Most uses of this object are detected in altars or directly used by the highest elder to hold to show his authority. The significance of the staff mostly comes from the pendants and the structure of the physical object which come together to bring meaning to the reason why someone may be in possession of this object.

Staff of Oxala Annotated Bibliography

Beier, U. 1956. Nigeria magazine: Obatala festival, 10-28.

Cahn, Peter S. “Brazil.” In Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2nd ed., edited by

Harding, Rachel E. “Afro-Brazilian Religions.” In Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd ed., edited by

Lindsay Jones, 119-125. Vol. 1. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. Gale Virtual Reference Library

ROCA, ROGER SANSI. “Catholic Saints, African Gods, Black Masks and White Heads: Tracing the History of Some Religious Festivals in Bahia.” Portuguese Studies 21 (2005): 182-200.

Thomas Riggs, 217-226. Vol. 2, Countries, Afghanistan to Ghana. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2015. Gale Virtual Reference Library

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Face of the Gods: The Artists and Their Altars.” African Arts 28, no. 1 (1995): 50-61.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of The Spirit. New York, New York: Random House Inc, 1983

Jamie Bottino

Rel 095

11/6/17

There is more than what meets the eye; an old saying that resonated through my head as I entered the “Spirited Things” exhibit at the University of Vermont’s Fleming Museum for the first time. The exhibit features sacred artifacts and altars sourced from West African religion, as well as the various diasporas that resulted from the displacement of African peoples as early as the 16th century. Passing each display, I was captivated by the individual parts that define altars as a whole as well as the orientation of individual objects in the museum space. Each artistic representation possessed a degree of complexity that I had never before seen at such volume. As I skirted the corner to view the second half of the exhibit, I spotted one particular encased object that stood alone.

Labeled “Staff of Fate” (Opa Osun), this piece drew me in among other artifacts because of its isolated arrangement in the context of the museum. As I approached the object, I realized that it contained many rusted limbs hinting at its old age. After reading the provided label for the staff, I discovered that it was a product of iron craftsmanship with an exception to its restored base. The object appeared to have levels near the top and bottom that resemble two distinct rings. Lining the outside of each ring are many small iron sculpted birds that face the stalk of the staff. Between both of these rings, a larger iron sculpted bird faces outwards in a fashion that resembles guidance and leadership. The larger bird is also adorned with a circular head piece and wings that extend far beyond its body, qualities the lesser birds lack (Duke University 2015) The very top of the staff contains a conical shape attached to a tray that leads down below the upper-ring. Adjacent to the tray, 4 long and narrow rusted bells are fastened to the object, and this is symmetrically represented below the lower-ring as well.

My basic understanding of staffs and their representations from other cultural examples led me to wonder if the Opa Osun garnered a certain force that could be manipulated by those who managed it. If the Opa Osun is interpreted in this way, what powers can be transmitted by the staff and who guides this power? In my writing, I will explore the substance of the Opa Osun Staff in Yorubaland in addition to the function of staffs and their operators in the context of ancient Yoruba tradition. By investigating these questions about the nature of the Opa Osun, I hope to reveal a heightened perception of religious artifacts in West Africa and the New World.

West Africa is home to ancient Yorubaland, a civilization where kingdoms once flourished in a framework of revolutionary urbanization (Okediji 1997). Within these kingdoms, artistic representations of sculpture containing highly refined naturalistic elements prospered and became a vital part of the religious traditions of the Yoruba (Drewal, Pemberton, & Abiodun 1989). During this period, craftsmen became highly skilled in the creation of sculpture using metals such as copper, brass, and bronze. The Opa Osun Staff is an example of the refined craftsmanship that characterizes the artistic creations of Yoruba people. A time considered a period of enlightenment in West Africa ended with the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, resulting in various diaspora in the New World. Forcefully relocated to a foreign frontier, Yoruba traditionalists brought their religious devotions overseas and practiced them behind closed doors amidst the ruthless bearings of slave life (Okediji 1997). The Yoruba expressed an unprecedented level of hope despite grim realities in the New World. Resilience played a crucial role in preserving the artistic creations of the Yoruba, and the Opa Osun Staff is no exception.

Religious artistic creations and tools significant in Yoruba culture are surrounded by a concept known as ase. Ase is a foundational power that concerns the state of living and nonliving things such as a staff. The phenomenon of ase can also be understood as a self-pertaining spiritual force that contains traditional medicinal answers (Abiodun 2014). There are many aspects of ase, however the most relevant to the Opa Osun is the role of ase as an activation of religious objects so that they may function accordingly. Artwork in Yorubaland is charged with ase, as it allows the visual representation of the work to transcend what others believe art to do. For example, staffs wielded by priests in divination processes are used to implement ase in the context of the ceremony. By establishing ase with a staff similar to the Opa Osun, priests can manipulate the fate of those who seek aid in their lives (Abiodun 2014). This insight accounts for the alternative name of the Opa Osun in the blurb beside the object in the museum, “Staff of Fate”. Another instance of a staff acting as a functional body can be found in an ancient Yoruba verse. In the verse, a cripple is instantly liberated from his state by just one touch from a healing staff (Abiodun 2014). The Opa Osun acts as a healing tool by harnessing ase in these instances of staff function. It is important to note that both scenarios of staff function detail that the operators of the staff have a higher status than a common individual.

The Opa Osun has also been used as a weapon against destructive forces such as death. In a ceremony referred to as Itefa, a religious leader known as a babalawo sacrifices a cock and uses the staff to arrange the body of the sacrifice. The ceremony involves the dismemberment of the animal, beginning with a swift ending of the cock’s life to ensure that death receives the offering instantly. Attending participants are touched on their heads with the head of the cock before it is then placed on the Opa Osun Staff. Following this, the babalawo takes the wings and feet of the sacrificed cock and touches them to the shoulders and feet of the ceremony’s participants before once again arranging them on the staff (Drewal & Thompson 1989). By doing so, a babalawo satisfies death with a cock in place of the members in attendance. The Opa Osun acts as a deterrent of future destruction in this case because the sacrifice of the cock ensures resilience against harm in the lives of the participants as well as the lone babalawo (Drewal & Thompson 1989). The Opa Osun can only be guided in this practice because its power cannot be entirely harnessed by the senior official. In other words, the staff is operated through influences, not direct actions.

The Opa Osun is demonstrated as an object that traditionalists look to for guidance in the present and future. In Yoruba culture, staffs are in fact charged with forces that can be manipulated by practitioners. Ancient verses and ceremonial divination allows me to suspect that the superior life force of ase is potent in power staffs similar to the Opa Osun. These comparable staffs serve a purpose of healing individuals who require aid as well as determining fate. The Opa Osun is also a medium to satiate destructive forces that threaten the well-being of practitioners. The sacrificial systems employed during the Itefa ceremony are telling of a complex transmission involved in the staff’s function. Both cases of staff power manipulation allow me to deduce that staffs in Yoruba culture are able to function as force synthesizers.

Staff power was and still is significant to Yorubaland inhabitants, and the principles of staff function were carried over to the various New World diaspora that resulted from the slave trade. From dissecting the use of staffs and their significance to Yoruba tradition, it seems natural that they would be implemented in the New World. Staffs served the purpose of limiting destructive futures and healing, therefore they would be applicable to the daily routines of an oppressed slave. Resilience allowed the Yoruba to prevail through hardship, and the Opa Osun symbolizes the hope retained by those subjugated.

I think back to the day I first laid eyes on the Opa Osun. A simple visit to the Flemings Museum paired with a quick reading of the information on the artifact was not nearly enough to understand the full potential of the object. I approached the object as if was a museum piece, when in reality the object is a functional entity that plays a critical role in religion (Thompson 1993). My experience with this object is representative of a cultural disconnect between Black Atlantic religions and Western society. Accurate assessments of Yoruba culture can only be reached if one analyzes the traditions in question with a curious and open mind, aware that art is much more than just a visual representation.

The Opa Osun Staff was theorized to be a reciprocating object of power due to a preconceived notion of staffs in other cultures. I also questioned the individuals who guided the power of the staff and the operations that surrounded its functioning. Upon research, I gathered that the Opa Osun has the ability to manipulate power, specifically the fate and resilience of one’s life. I also validated the figures who guide the powers of the staff, those being senior officials such as a babalawo. My findings leave me with a heightened perception of African religious power objects and the crucial role of a iron crafted staff in the lives of Yoruba religious affiliates.

Bibliography

Abiodun, Rowland. Yoruba Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2014. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107239074.

Drewal, Margaret Thompson, and Henry John Drewal. “An Ifa Diviner’s Shrine in

Ijebuland.” African Arts 16, no. 2 (1983): 61-100. doi:10.2307/3335852.

Okediji, Moyo. “Art of the Yoruba.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 23, no. 2 (1997):

165-98. doi:10.2307/4104382.

“Opa Osun, D027.” The Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic. Accessed October 30, 2017.

http://sacredart.caaar.duke.edu/.

Opa Osun. 2015. The Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic, Duke University, Durham.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Face of the gods: the artists and their altars. 1st ed. Vol. 28. Museum

for African Art, 1993.

Walking into the Fleming Museum’s Spirited Things: Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic Exhibit, you’ll see everything from emptied rum bottles that have been transformed with beads and other materials into representations of the gods, to small statues that are meant to control the spirits of the dead allowing them to be used by the living. What caught my attention though was a glimmer a blue from the corner of my eye. Looking to my left there is a glass container containing various objects that are dedicated to the goddess Yemaya, the goddess of the sea who is often perceived as a mother to all, from Cuban Santeriá, or as it is more commonly known in Cuba, as Regla de Ocha, though there were three other objects what draws the eye most is the most delicate. A small crown of silver, comprised of 7 smaller crowns, each of which has two blue gems catching the light that showcases the object draws the eye of the viewer. Silver chains hang from the crown, each with their own unique metal object which represent the goddess or one of her allies, drawing the viewer deeper into the story behind the crown. In this analysis I’m going to describe the meaning of the crown and the various parts that comprise it, and then I’m going to discuss how the crown is a representation of both the African Diasporic religions and how syncretism and hybridity play a role in the creation and the design of the crown as well.

Altar crowns are a central part on many personal altars found in the homes of worshipers. Altars crowns are placed on top of soup tureens, which we learned in class, are decorated to match the orisha being worshipped, in the case of the altar crown that was made for Yemaya, the colors would be blue and white. Within these tureens symbols to the gods or objects that please the gods can be found, making the gods present on the altar. The altars and the objects that are placed on them are embodiments of the gods which means they are given the same respect. This means that the people who worship them wish to provide them with the best and most beautiful objects, and we can see that with the delicate beauty of the altar crown. By making sure that the objects are regularly cleaned and maintained as well as giving them offerings of food and drink they make sure that their gods on the altar are happy and well maintained. This crown specifically, is used on altars of Cuban Santería/Regla de Ocha altars for the goddess Yemaya. Each piece of the crown can clearly be linked back to Yemaya or some other god or goddess of the Santeriá religion. It doesn’t just do this though, the object is able to link Santeriá back to its religious origins in the Yoruba religion with the chains that hang down off the crown. The chains that hang down create a veil, similar to those that are found on the crowns of the African Yoruba monarchs, connecting the current practices to those of its past.

To understand how the crown is made and the reasoning behind each portion of the crown we must first understand the goddess whom the crown is made for. According the the website for the Santeria Church of the Orishas,Yemaya’s most sacred places in nature are those associated with water, the oceans, lakes, and lagoons, the color that represents Yemaya or her caminos (avatars or “roads”, which essentially are different versions of herself) are the colors blue and white, since she is the goddess of the sea. Her sacred number is 7, for her 7 caminos, and representative of the 7 seas. Yemaya influences more than just the sea though, as she is seen and known as a mother to all, she also influences family and women’s issues, pregnancy, children, and she is also associated with healing. Our ability to understand the goddess that the crown is made for will allow us to create the connections to understand the creation of the crown as a whole.

The crown contains many parts that we can link back to the goddess Yemaya, the 7 smaller crowns, 7 blue gems found in between each of the crowns all connect back to her sacred number. As well as this there are 21 chains that hang down from the crown, each of these chains have small silver charm that represents either yemaya or one of her many allies, as well as her sacred number since 21 is a multiple of 7. The key is associated with Elegguá, which according the the website for the Santeria Church of the Orishas, is the god of all roads, cross roads and doors, without his blessings nothing can get done as he allows the prayers of those who practice Santeriá to reach the intended orisha. The horseshoe, the hammer, the hatchet, the sickle and the scythe, the anvil, the sledgehammer, the knife, the saw and the machete all represent Yemaya’s husband Ogún, who is a powerful warrior, who defends those who worship him. The snake represents her other husband Obatalá, who is the eldest and most powerful of all the orisha, he is said to be the father of many of the other orisha and is said to be the owner of all heads, both spiritual and outer. The lightning bolt and the sword represent her son Chango, who is the god of thunder, lightning, and leadership. The 3 quills to represent her daughter-in-law Obba, who is considered to be the goddess of marriage and home, who waits for her husband Chango even though he cheats on her with the other goddesses. The sun, moon, ship’s wheel and the anchor embody Olokun, who is the goddess of the deep sea, some of the same charms are also sometimes associated with Yemaya. The charms that remain represent Yemaya and her own powers.

This object relates directly to the readings that we do in class as it demonstrates both a direct example of how the african diaspora works as is demonstrated throughout the religions as well as demonstrating the theories of hybridity and syncretism in a way that we can look at and see with our own eyes. To understand though how the object demonstrates how Santeriá is a diasporic religion of how it demonstrates syncretism, we first need to define both of the terms to truly understand and see the connection between the object and these topics.

Diaspora can be defined as a scattered population who originated from one location or as a population that has migrated from one location to another. Diasporic religions though are composed of memories of its place of origins and how it has changed since moving on. I believe the best description of a Diasporic religion though comes from Paul Johnson’s chapter Religions of the African Diaspora when he says, “African diasporic religions are transformed as they are accommodated in new sites and populations” (Johnson, 2013, 516). I think that this is the best definition because it relates to how the religions came over, and how they have changed. These Afro-Caribbean religions were brought over by the slaves taken out of their native countries during the Transatlantic Slave Trade, they brought their religions over, but because they were forced to hide their religion some of the aspects changed, transforming the religion into something new. This is clearly demonstrated in certain aspects of the crown, specifically with the chains that hang down with the small charms, the chains resemble the veil found on the on the African Yoruba monarchs, the classic traditions of the religion showing through despite the oppression of the religion, traditionally the objects that are attached to the chains would be found inside of the soup tureen. As well as the connecting the crown to its Yoruba traditions we can connect the goddess herself back, in Yoruba tradition the oriṣa would be known as Yemọja but she has become Yemaya in Cuban Santeriá through the African Diaspora. This is a demonstration of the african diaspora because there is a clear connection to Santeriá and its Yoruba roots.

Syncretism is the most commonly used word when it comes down to the mixing of different aspects of a religion into one, or when one aspect of a religion is influenced by another religion or culture. Though syncretism is used most commonly used when dealing with topics of religions, the word hybridity is used when dealing with the combination of different organisms, the two words are usually a package deal though, when you hear one, you will most likely hear the other, because they deal with similar topics. In Johnson’s chapter Syncretism and Hybridization, he says “Syncretism and hybridity require ‘worlds’ of parallel entities that can it could be juxtaposed or joined. We don’t usually imagine or posit the creole, hybrid or syncretic possibilities of, say, dogs and plants, or Augustinian theodicy and snow tires, because such entities occupy different worlds.” (Johnson, 2016, 766). This shows us the link between hybridity and syncretism because it explains that to be used the religions, or organisms that they are combining need to be that of the same “world”, which just means that they need to have something in common, in this situation we are talking about religion. The altar crown demonstrates syncretism through how the altar crown for yemaya shares certain aspects with the traditional styles of European crowns. This is a demonstrates of syncretism because of the roles that crowns play in Europe and in aspects of christianity. The crown is a symbol of royalty and the monarchy, this is a shared feature in both altar crowns, as altar crowns also symbolize royalty among the oriṣa, and the European crowns so the integration of European styles in with the traditional Yoruba style of crowns is a demonstration of hybridity. Crowns do more than just represent royalty though, in the Catholic religion it is believed that those who go above average in certain aspects of the religion will receive a crown when they enter in the kingdom of heaven, the crown of righteousness for example, or the crowns that were worn by the monarchs as they traditionally had a role in the church. This is an example of how the European crowns play a role in the religion which makes the combination of the European styled crown and the Yoruba style crown an example of both hybridity and syncretism.

The altar crown for Yemaya in Cuban Santeriá is a clear demonstration the definitions of syncretism/hybridity and the African Diaspora. Examples that prove this can all be found in the crown and in the reasons behind the various pieces that come together to form the finished product. From the 7 blue gemstones meant to represent Yemaya, to the charms hanging off the chains which represent Yemaya and her allies. The 7 small european looking crowns that bring back the memories of when they had to incorporate catholic traditions into their religion so that they could practice it in secret, and the chains that hang down off the crown connecting it back to the traditional crowns of the religion it was based off of. Each of the aspects of the crown demonstrate how the crown and Santeriá as a whole is a diasporic religion and the aspects that it took in through syncretism.

Bibliography

Matory, J. Lorand. ms. The Fetish Revisited: Marx, Freud, and the Gods Black People Make.

Flores-Peña, Ysamur, and Roberta J. Evanchuk. 2011. Santería garments and altars: speaking without a voice. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Matory, J. Lorand “Artifacts.” Artifacts | The Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic. Accessed October 30, 2017. http://sacredart.caaar.duke.edu/artifacts/1283#.

“Yemaya.” Santeria Church of the Orishas. Accessed October 30, 2017. http://santeriachurch.org/the-orishas/yemaya/.

Johnson, Paul Christopher. 2016. “Syncretism and Hybridization.” In The Oxford Handbook in The Study of Religion. Edited by Michael Stausberg and Steven Engler, 754-69. Oxford University Press.

Johnson, Paul Christopher. 2013. “Religions of the African Diaspora.” In A Companion to Diaspora and Transnationalism. Edited by Ato Quayson and Girish Daswani, 509-20. Blackwell Publishing

Noah Stommel

Obba Soup Tureen

Santeria Birthday Altar

In a corner dedicated to gender representation in Yoruba religion at the Fleming Museum’s Spirited Things exhibit, alone sits a highly decorative Cuban Santeria soup tureen dedicated to the goddess Obba. As the plaque next to the tureen states, legend has it that this Orisha, the goddess of domestic duty and marriage, was tricked by her co-wife to Shango, the Orisha of thunder, to cut off her ear and serve it to him in a stew to win his affection. The soup tureen as an object of worship therefore seems ironically fitting. From an aesthetic standpoint, the tureen appears to be made out of a shiny ceramic material, and is painted bright pink. Both side handles and the single handle on the lid are embellished with gold paint. Strings of threaded golden beads adorn the tureen’s sides, and on opposing sides, as well as around the top handle, cowrie shells are glued to form stars. At the center of the opposing stars lie even more threaded beads.

Cuban Santeria is a religion syncretized between Catholicism brought to Cuba by Spanish colonists, and African-diasporic religion, introduced to the island through the African slave trade (Clark 2001, 21-22). The use of the soup tureen in Santeria has adapted from its origins in West Africa due to the influence of this religious syncretism, which is the fusing of religions to form a new one (Johnson 2016, 760-761). However, through further examination of this tureen, it becomes apparent to me that its use is more so influenced by Yoruba-derived practices than by Catholicism.

The Catholic and Yoruba influences that both play at shaping this object’s purpose and activation methods was part of what captured my interest in this object. I believe that due to cultural mixing on the island of Cuba, there is much to be understood about the true purpose and meaning behind such a soup tureen. Aside from the tureen’s beauty, its lack of ritualistic context in the museum drew me in further. Obba’s tureen was placed closely to the Santeria birthday altar (also pictured), which, as the museum plaque indicates, includes several soup tureens or “soperas” richly decorated with objects made to invoke the presence of other Orisha, or gods, in Yoruba religion. Crucial factors of this altar are varying elevations of the soperas as well as color and the use of other objects with symbolic meaning. Obba’s tureen had a contrasting lack of context. Simply sitting in a display case, I wanted to learn more about the potential for forces to be activated within it, stimulating the presence of Obba, and fulfilling its use as a ritualistic object. In my essay, I will first explain the origins of such an object as seen in West Africa, the homeland of Yoruba religion. Then I will go into depth on how Yoruba religion has combined Catholic traditions to form the practices we see in relation to this object in Cuban Santeria today. Ultimately, I hope to prove that although Catholicism does play a role in Santeria, Yoruba religion continues to be the chief influence in Santeria and the use of that religion’s divining objects.

On their forced journey across the Atlantic, Yoruba people encountered a huge change in setting that required their religion to adapt. This adaptation meant that although much of the basis of the religion stayed the same, certain rituals had to be altered to better fit their new environments. This theory applies to Obba’s soup tureen, not just with the exterior aesthetic, but also with what lies within; consecrated shells or stones “fed” animal blood and herbs (Martin & Luis 2012, 164). The significance of these stones is that they “represent the living presence of the Orisha on the Santeria altar. Like the consecrated host that Catholic doctrine deems the actual body of Christ, these ‘stones’ are the Orisha” (Clark 2001, 37). This parallel seen between Santeria and Catholicism is a prime example of European influence in Cuba. However, while we see Catholicism affecting the contents of the tureen, the overall purpose and idea of spirit activation associated with such an object is still largely a product of Yoruba religion (Bascom 1950, 66-67). In fact, practitioners of Yoruba religion use containers and vessels in their faith as symbols of generosity, respect, and honor to the Orisha (Thompson 1983, 13). Furthermore, it is important to note the orientation of Santeria around African-inspired Orisha (Bascom 1950, 64), and not one central Christian God. The fact that Yoruba customs live on in Santeria, despite competing Catholic contribution, indicates the preservation of native African culture.

Further important to Santeria rituals are palm nuts, cowrie shells, and water. This can therefore account for aspects of the decorum present on the outside of the tureen. These elemental factors, in combination with herbs, blood, and stones breathe a life force, known to Yoruba practitioners as “Ase,” into the tureen, which is necessary both for life and for performing religious rituals (Brown 79). A byproduct of Yoruba religion seen in Santeria is the requirement of Orisha to manifest themselves on Earth in containers or vessels, where they can reside. Human bodies and drums can also serve as a vessel for Orisha habitation (Murphy 2012, 79-80). The color aesthetics of the Orisha’s containers is also highly meaningful in Santeria.

The color scheme of Obba’s soup tureen is explained as being highly dependent on the individual beliefs that Santeria practitioners have on the color preferences of the Orisha themselves. One practitioner explained that for her, “Obba wears yellow and white beads for no other reason than ‘that’s the way I received it’” (Brown 1996, 99). Granted that there are some guidelines to color representation of the Orisha, this is a mentality held greatly by Yoruba practitioners, for whom there is not a particularly dictating religious code of worship that must be followed (Brown 1996, 100). Of course, Christianity also allows for a level of interpretation of religion among its followers, so while the colors representative of Obba are heavily influenced by Yoruba, the basis of individual interpretation could find itself in either religion.

A highly possible explanation for syncretic imbalances associated with Obba’s tureen is that throughout the colonial era, there were many instances of Santeria being oppressed by the dominant European society. This theme is seen “everywhere across the early black Americas [because] covert altars encoded the richness of sacred memory to unite servitors in sustaining faiths” (Thompson 1993, 21). By veiling one’s African-derived religious practices behind a Catholic pretense, Santeria worshippers were able to preserve their rituals and beliefs, even while under the watchful eyes of the Catholic Church.

Some scholars on African-diasporic religions argue that there is a scholarly bias in classifying Santeria as a byproduct of Catholic syncretism. They state that “the origin of this religion is in the forests of the country previously called Yorubaland, better known today as Nigeria. From there comes what we today know as Santeria” (Fardon 1995, 83). Adding to this belief is the fact that “Spanish law insisted that slaves be baptized as Roman Catholics as a condition of their legal entry into the Indies” (Murphy 1988, 27). The forceful integration of Yoruba people in a Catholic-dominated society, although influential on the resultant Santeria, would not have created the desire to assume the practices and values held by oppressors. It is more plausible to argue that “Caribbean religions such as Santeria… are often cited as examples of syncretism because the religions involved have such different histories and because the historical materials about them are relatively recent and full” (Murphy 1988, 120). There is no avoiding the fact that Catholicism and Yoruba religion mixed to produce Santeria, but it is reasonable to suggest that given the belief systems held by a vast majority of those enslaved in Cuba, an emphasis on Yoruba religion was preserved in the island’s Afro-Caribbean culture.

As I came to learn through my research of Obba’s tureen, there is a definite degree to which syncretism of Catholicism and Yoruba religion has had on the overall use of the Obba’s tureen, as well as Santeria itself. However, I would assert that there is still more of a Yoruba emphasis in the aesthetics of Santeria soperas, an essential counterpart of the greater religion. Through information provided on how Yoruba beliefs maintained a tight grip over incoming slaves transported from Africa, and how European-enforced Catholicism influenced Santeria practice, the predominant influences on modern usage of Obba’s soup tureen have become clearer. This syncretized religion shows its true colors in both the objects that it so highly regards in worshipping the Orisha, and in aspects of the theological belief system. I believe that this trend of religious mixture makes itself apparent not only in Santeria, but in all other New World African religions, or on a larger scale, any religion whose followers have undergone voluntary or forced cultural coalescence.

Now that I have come to understand the context of the animation and aesthetics of the tureen, I am more interested than ever to witness the process of stone consecration and the subsequent activation of Obba. When first viewing this object, my interest was sparked by its placement in the museum, relatively isolated from others that serve a similar purpose. I believe that this therefore served as a basis to learn more about other objects of its like, and the human history that has forced its adaptation.

Bibliography

Bascom, William R. “The Focus of Cuban Santeria.” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 6, no. 1 (1950): 64-68.

Brown, David H. “Toward an Ethnoaesthetics of Santeria Ritual Art: The Practice of Altar-Making and Gift Exchange.” Santeria Aesthetics in Contemporary Latin American Art (1996).

Clark, Mary A. “”¡No Hay Ningún Santo Aqui!” (There Are No Saints Here!): Symbolic Language Within Santeria.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 69, no. 1 (2001): 21-41.

Duke University . “Soup-Tureen Altar Vessel (Sopera) for the Santeria/Ocha Goddess Obba.” Accessed November 5, 2017.

Fardon, Richard, ed. Counterworks: Managing the Diversity of Knowledge. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Johnson, Paul C. “Syncretism and Hybridization.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Study of Religion, edited by Michael Stausberg and Steven Engler, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Jones, Rachel E. “Art Review: ‘Spirited Things: Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic,’ Fleming Museum.” Seven Days, October 4, 2017.

Martin, Oba F., and William Luis. “Palo and Paleros: An Interview With Oba Frank Martin.” Afro-Hispanic Review 31, no. 1 (2012): 159-68.

Murphy, Joseph M. “Chango ‘ta vein’/ Chango has come”: Spiritual Embodiment in the Afro-Cuban Ceremony, Bembé.” Black Music Research Journal 32, no. 1 (2012): 69-94.

Murphy, Joseph M. Santeria: An African Religion in America. Boston: Beacon Press, 1988.

Thompson, Robert F. Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy. New York: Random House, Inc., 1983.

Thompson, Robert F. “Overture: The Concept “Altar”.” Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americas (1993).

Jack Bechtold

10/30/17

TAP: Religions of the Black Atlantic

Professor Brennan

Object analysis

I will be talking about the Cuban Santería and the god Eleggua; specifically, an artifact of the Eleggua exhibit in the Robert Hull Flemming Museum, in Burlington VT. This artifact is the house of Eleggua. Eleggua is the Cuban god of the crossroads and of entrances. I chose Eleggua and his house because of its strategic placement in the exhibit, and because of the detailed craftsmanship that caught my eye. This object is a Cuban style house ornately decorated with beautiful red and black beads these beads. These have been arranged in patterns that add something to the house called ashe -the life force surrounding all beings. The entryway of this house is a stone face of Eleggua. His eyes, nose, and mouth are made from cowry shells. This house is dominated by the colors red, white, and black making the piece a unique artifact and shrine to Eleggua. This house’s structure was built with wooden walls and ceilings; each section is painted a specific color depending on the part of the structure. The walls and ceiling of this house are painted red. The house itself sits on a dual-layered base. This base consists of two boards that have been glued together. The top board has a cut out in it for the dimensions of the house and is painted the same red as the house. The bottom board is painted entirely black, making the floor and shadows in the house black. The house is then outlined in cowry shells which used to be a form of currency in Nigeria and other Yoruba dominated lands. This use of shells is supposed to show wealth, status, andpower. It is Eleggua and it is a symbol of the crossroads themselves. The artifact is strategically placed at the beginning of the exhibit – you are supposed to pray to Eleggua before you enter a house, and in the setting of an exhibit of African religions, you need to pray to Eleggua so that he may open the door to allow you to enter and see all the secrets of his world. Eleggua was demonized due to poor understanding of indigenous concepts of power during syncretism between Christianity and the religions of the African diaspora.

Cuban Santería originated from the African diaspora and is one of the most popular religions in the “Black Atlantic”. Many of the Africans taken to the colonized islands of South America during the slave trade were people of the Yoruba faith. There were Africans from all over the western shore of their homeland continent in Cuba and these people had a multitude of versions of faith. While under the constant oppression of slavery these people came up with Cuban Santería. Cuban Santeria is a religion based on indigenous power concepts. There is a multitude of different gods with different specialties. Eleggua is the god of the crossroads and entrances. He holds the ability to open and close the doorways to our destiny. Worshipers need to appease Eleggua through ceremonies, songs, and rituals to make him inclined to help you. A frantic parent with a sick child would pray to Babalú Ayé, the god of disease and epidemics for healing. But, if you do not appease Eleggua, he might not be inclined to open the doorway for communication between you and Babalú Ayé. This creates an interesting relationship between the worshiper and the gods. The worshiper has the ability to harness each god to ask for help, but if Eleggua doesn’t want to help then there is nothing to be done.

This mischievous nature has given Eleggua a bad name. In ‘Flash of the Spirit’ by Robert Thompson, Mr. Thompson talks about Eshu who is the Yoruba version of Eleggua is characterized as “ ‘The devil’ ”(Flash of the spirit page 19) by missionaries. Thompson then continued to describe Eshu and show the reader that he in fact isn’t “The Devil” but is “Outwardly mischievous but inwardly full of overflowing grace” (Flash of the Spirit, page 19). Mr. Thompson notes that he cannot be characterized even by his own people due to the fact that Eshu has many different names such as Eshu, Elegbara, Elegguá, and Elegba. “Even his names compound his mystery” (Flash of the spirit page 19). Eshu is known as “owner of power” (Flash of the Spirit, page 19). It is incredibly interesting how Eleggua has this power that connects all of these followers with their gods and for the most part binds their society together.

Eleggua has been mischaracterized as the devil by Christians because of a lack of understanding of indigenous concepts of power that is a crucial aspect, not just of Cuban Santería, but of all Afro- Atlantic religions. According to Mr. Falola and Ms. Genova and their work on ‘Orisa -Yoruba Gods and Spiritual Identity in Africa and the Diaspora’. In the Yoruba religion, Eshu was one of, if not the first, divinities created by Olodumare who is “(The supreme being) the source, origin, and creator of all beings, including divinities,” (Orisa Yoruba Gods and Spiritual Identity in Africa and the Diaspora, page 129). If this is true, then Eleggua may have had a hand in creating the world and man. Taking this belief into consideration, Eleggua cannot be the devil because he is both benevolent and malevolent, while the devil is only malevolent. If Eleggua really was the devil, antichrist, Apollyon, Beelzebub, etc. Then do you think he would have helped Olodumare create the world, the other divinities, or answer the prayers of the people? The paradox in this idea is “that can a creature be more powerful than his creator,” (‘Yoruba Gods and Spiritual Identity in Africa and the Diaspora’, page 131). Olodumare gave Eleggua the power of complete control over the communications sector of religious communication, which makes him so powerful that he has some sort of free will that he likes to exercise by being both benevolent and malevolent.

Santería offers variations to that story, keeping the message is the same. According to David H. Brown, ‘Santería Enthroned’ , Eleggua was created by the all-powerful God Obatala who is the “Owner of all heads” (Santería Enthroned page 126) or the owner of all destinies. In the Santería religion, you are thought to have an inner head which is your destiny. Eleggua’s job is to open the doorways to help you find your inner destiny. But, can the creature be more powerful than his creator? if Eleggua is truly in control of all religious communications and he is a “trickster” then he is going to want to use his powers for benevolent and malevolent things, but that doesn’t make him the devil because he isn’t pure evil. He is as imperfect as the humans he is scribe for.

Eleggua was demonized due to a misunderstanding of indigenous conceptions of power. The key to understanding religions like these are looking at the gods and the power structure while separating your own concepts of religion. Once you have separated your own concepts of religion from the religion at hand you can analyze everything through a scientific lens. What makes a scientific lens so important is it filters out the bias from the fact. This ability is the defining difference between the way of thinking that leads you to Eleggua being synonymous with the devil, and seeing his true place as the “owner of power” (Flash of the Spirit, page 19).

Brown, D. (2003). Santería enthroned. Chicago (Ill.): University of Chicago Press. pp. 126

Mason, M. (2004). Living Santería: Rituals and Experiences in an Afro-Cuban Religion. pp.7, 95, 96.

Falola, T. and Genova, A. (2005). Orisa Yoruba Gods and Spiritual Identity in Africa and the Diaspora. 1st ed. Trenton, NJ 08607: Africa World Press, Inc., pp.129-139.

Thompson, Robert Farris. 1984. Flash of the Spirit. New York City, New York: vintage books.

Scarlet Shifflett

When I walked into the museum I expected to see dusty objects with no personality on a shelf. I wondered how I would be interested enough to write a paper on an object that had nothing to do with my culture, but then I stepped into the exhibit. Each room had significantly changed from its original state just a week before, there was suddenly life in each object. I walked the designated path looking at the altars with awe, everything fit together perfectly, but one room was so beautiful I had to stop.

The first thing I noticed were the walls. Where there was once plain white was now covered in blue cloth. Nothing was left uncovered by extravagant blue patterns, from flowers to sparkles. The cloth surrounded fourteen altars, each with their own personality shown with colors and objects. Every altar was unique in its own way, but I was drawn to one in particular, Oya. I did not know who this Orisha was at the time, I only knew her altar was the most beautiful and gave off a power none of the other surrounding altars did.

A copper crown with dangling charms sat on top of a soup tureen with bird handles. The first set of charms were all the same, a copper mask, while the second set contained a lighting bolt and a variety of farming tools, picks, hoes, and a machete. The porcelain soup tureen gave the altar a hint of cream color, allowing the red and maroon to really pop, while the birds added beauty with their carefully painted patterns. A horsetail whip was front and center, the long, silky black hair showed the elegance of the Orisha, while, along with the crown, also captured the royalty of Oya. Lying behind the whip was a wooden sword, covered with colorful beads that lead to another beaded handle with a mask dangling off. This handle was not as sturdy as the one on the whip, allowing me to assume this weapon could only be used by someone skilled enough to understand the delicate motions needed to swing the sword. This altar was the only one out of fourteen to have a picture of a catholic saint, which was shown on a red cloth accented with colorful beads. The entire altar was decorated with green, orange, purple, blue, brown, pink, and yellow beads, giving the red cloth more color and character.

I was drawn to Oya’s altar based on the beauty and power it gave off. The crown and whip told me the importance of this Orisha and the royalty she held, while the sword represented a worrier. I have never heard of someone of royalty fighting their own battles, and it was this reason why I chose Oya’s altar to be my object of interest.

My interest in the altar did not stop there, I wanted to know why someone would honor Oya, the goddess of storms and change, and how the objects on the altar embodied the orisha. In this essay I will give background information on the goddess Oya to show why people choose to honor this Orisha and the effects it will have on their lives. I will also discuss why this pedestal with objects on it is an altar.

The Oya altar is a part of a birthday altar. This altar comes from the Cuban religion Santeria and is an important part of a Santeria priest’s life. In Orisha Worship Communities: A Reconsideration of Organisational Structure Mary Clark describes what the typical birthday altar would look like on page 103, “The ceiling and walls of the designated space are covered with panels of fabric… the cloths form walls and a canopy that encloses the entire area.” This description accurately represents the altar that is housed in the Fleming museum. Another important aspect of a birthday altar is making sure each Orisha is being honored in their own way, as seen with the maroon and multi colored beads and the sword on Oya’s altar, page 104 states, “…small splash of color are incorporated into the pedestals and stands holding the pots and accouterments of the Orisha so each deity is represented by a cloth… each Orisha is surrounded by their particular tools and symbols.” This altar is meant to honor the priest’s Orisha, which they have chosen in previous ceremonies. If this altar was not in a museum then multiple rituals would occur to celebrate the priest’s birthday into the religion, “On the first day of the celebration… Each guest first greets the Orisha by prostrating herself on the mat placed in front of the throne… Godchildren of the hostess generally leave the ritually prescribed gift… Entertainment may include live drumming or recorded music…”, as described by Clark on page 105.