Scarlet Shifflett

When I walked into the museum I expected to see dusty objects with no personality on a shelf. I wondered how I would be interested enough to write a paper on an object that had nothing to do with my culture, but then I stepped into the exhibit. Each room had significantly changed from its original state just a week before, there was suddenly life in each object. I walked the designated path looking at the altars with awe, everything fit together perfectly, but one room was so beautiful I had to stop.

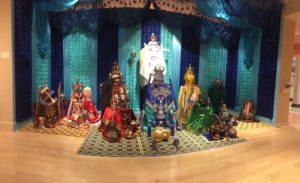

The first thing I noticed were the walls. Where there was once plain white was now covered in blue cloth. Nothing was left uncovered by extravagant blue patterns, from flowers to sparkles. The cloth surrounded fourteen altars, each with their own personality shown with colors and objects. Every altar was unique in its own way, but I was drawn to one in particular, Oya. I did not know who this Orisha was at the time, I only knew her altar was the most beautiful and gave off a power none of the other surrounding altars did.

A copper crown with dangling charms sat on top of a soup tureen with bird handles. The first set of charms were all the same, a copper mask, while the second set contained a lighting bolt and a variety of farming tools, picks, hoes, and a machete. The porcelain soup tureen gave the altar a hint of cream color, allowing the red and maroon to really pop, while the birds added beauty with their carefully painted patterns. A horsetail whip was front and center, the long, silky black hair showed the elegance of the Orisha, while, along with the crown, also captured the royalty of Oya. Lying behind the whip was a wooden sword, covered with colorful beads that lead to another beaded handle with a mask dangling off. This handle was not as sturdy as the one on the whip, allowing me to assume this weapon could only be used by someone skilled enough to understand the delicate motions needed to swing the sword. This altar was the only one out of fourteen to have a picture of a catholic saint, which was shown on a red cloth accented with colorful beads. The entire altar was decorated with green, orange, purple, blue, brown, pink, and yellow beads, giving the red cloth more color and character.

I was drawn to Oya’s altar based on the beauty and power it gave off. The crown and whip told me the importance of this Orisha and the royalty she held, while the sword represented a worrier. I have never heard of someone of royalty fighting their own battles, and it was this reason why I chose Oya’s altar to be my object of interest.

My interest in the altar did not stop there, I wanted to know why someone would honor Oya, the goddess of storms and change, and how the objects on the altar embodied the orisha. In this essay I will give background information on the goddess Oya to show why people choose to honor this Orisha and the effects it will have on their lives. I will also discuss why this pedestal with objects on it is an altar.

The Oya altar is a part of a birthday altar. This altar comes from the Cuban religion Santeria and is an important part of a Santeria priest’s life. In Orisha Worship Communities: A Reconsideration of Organisational Structure Mary Clark describes what the typical birthday altar would look like on page 103, “The ceiling and walls of the designated space are covered with panels of fabric… the cloths form walls and a canopy that encloses the entire area.” This description accurately represents the altar that is housed in the Fleming museum. Another important aspect of a birthday altar is making sure each Orisha is being honored in their own way, as seen with the maroon and multi colored beads and the sword on Oya’s altar, page 104 states, “…small splash of color are incorporated into the pedestals and stands holding the pots and accouterments of the Orisha so each deity is represented by a cloth… each Orisha is surrounded by their particular tools and symbols.” This altar is meant to honor the priest’s Orisha, which they have chosen in previous ceremonies. If this altar was not in a museum then multiple rituals would occur to celebrate the priest’s birthday into the religion, “On the first day of the celebration… Each guest first greets the Orisha by prostrating herself on the mat placed in front of the throne… Godchildren of the hostess generally leave the ritually prescribed gift… Entertainment may include live drumming or recorded music…”, as described by Clark on page 105.

While the altar I am studying is only a small part of a bigger altar, the pedestal supporting the objects portraying Oya is considered an altar because it is a form of communication to the Orisha and a way to worship the goddess. “Altars everywhere are sites of ritual communication…” this is stated by Robert Farris Thompson on the first page of Face of the Gods: The Artists and Their Altars. I saw a form of communication in the altar with the farming charms on the crown. If the altar was in its ritual context than those charms could represent a farmer in need of change with his crops. If the crop season had a lack of rain, the farmer would call upon the goddess of storms and change. Worshipping Oya on her altar would allow the farmer to ask for storms to come to water his crops, giving him the yield he needs. In another part of the book, Face of the Gods: Arts and Altars of Africa and the African Americans, Thompson says, “a place [altar] consecrated to devotional exercises. Altars, then, encompass sacrifice, prayer, and devotion.” The sword, crown, and whip, show devotion to Oya by representing her power and strength as a royal warrior. In a traditional setting food would be placed on the pedestal as a sacrifice to the the Orisha, and one would kneel on the mat under the altar to pray to the goddess. With objects communicating to Oya and food and prayer showing devotion, this pedestal representing Oya is an altar.

One website was useful when collecting information on the goddess Oya, www.orderwhitemoon.org, this source was able to give me a perspective from someone who actively worships Oya while most scholarly sources only gave an outside perspective. The website stated, “Oya is one of the most powerful African Goddesses (Orishas). A Warrior-Queen…She is the Goddess of thunder, lightning, tornadoes, winds, rainstorms and hurricanes. A Fire Goddess, it is Oya who brings rapid change and aids us in both inner and outer transformation.” Other information included the Orisha’s number, nine, her colors are maroon, dark red, purple, orange, brown and multiple other colors, and icons that represent the goddess include, whips, masks, and swords. All these representations can be seen on the altar present in the museum; maroon and dark red cloth cover the podium the objects rest on, beaded accents throughout the objects incorporate the other colors, purple, orange, and brown. There is a horsetail whip, sword, mask, and a crown made out of copper with mask charms and one lightning bolt all represented the icons associated with the Orisha. This website also includes the foods that should be given to Oya on the altar, eggplants, grape wine, kola nuts, and fish.

One would honor Oya if they want a change in their life and would do so through the altar. The previously mentioned website tells how someone would call upon Oya when that person’s desire for change needs to be heard. First a person would light the candles present on the altar. Before I continue I want to say that the altar in the museum does not have candles because it is not an active altar dedicated to Oya, it is simply an altar meant to be viewed in a museum. This is a key difference between objects present in a museum and those that reside in the context they were meant to be in. After that person has lit the candles they will resite a passage that according to the writer of this website will invoke the presence of Oya; the passage is the following,

“Oya, Lady of Storms,

Oya, Bringer of Change,

Oya, Warrior of Women,

You who command the winds

And protect the souls of the dead

You whose domain is the tornado, the storm, the thunder,

I ask for you to join me here tonight

And help me bring positive change and action into my life

Hail, Oya, Lady of Storms!”

Once Oya is invoked you should talk to the goddess about the changes you want to make in your life and how you will get there. The most important change that you want to make should be written down and left on the altar as a reminder. Thanking Oya, place offerings on the altar, these can consist of any of the foods listed above, and the once again recite the passage as a goodbye to the Orisha.

Even with thirteen altars surrounding Oya’s it is clear she is a powerful Orisha capable of great things. These great things involve controlling wind and storms and bringing change to those who honor her appropriately. Oya can be honored through an altar where food will be given to the goddess and devotion is shown through objects. As long as there is a form of communication and a way to worship the Orisha than that object will be considered an altar. In conclusion, if someone is in need of change in their lives than they should strongly consider building an altar to the Orisha Oya.

Order of The White Moon. Oya: Lady of Storms. http://www.orderwhitemoon.org/goddess/oya-storms/Oya.html.

Thompson, Robert. Face of the Gods: The Artists and Their Altars. UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center, 1995.

Thompson, Robert. Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americas. The museum for African Art, New York, 1993.

Mary, Clark, Orisha Worship Communities: A Reconsideration of Organisational Structure. United States of America: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2011.