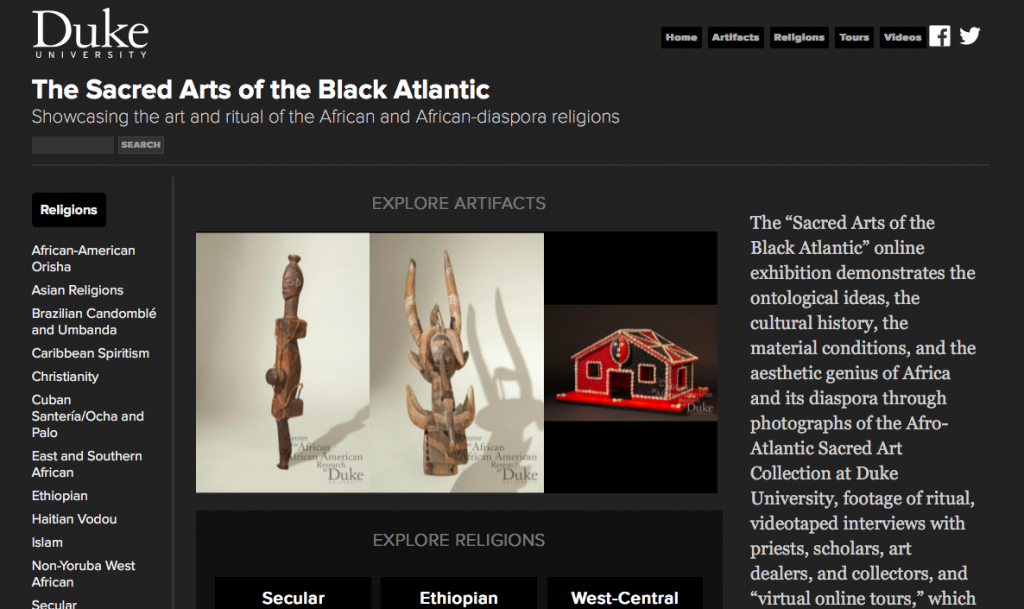

Most of the objects that appear in the Spirited Things exhibition at the Fleming Museum are catalogued on the Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic (SABA) site.

Monthly Archives: September 2017

Class Notes, Week Five

You can access the link for the class notes document below:

Stirred Not Shaken: Religious Cocktails in Nigeria

In Sacred Journeys: Oṣun-Oṣogbo the Nigerian festival is shown in its modern context, as a pilgrimage, of sorts, for not only peoples from around Nigeria (and surrounding countries) but also for those hailing from the New World. You may ask yourself, “What the heck is Oṣun-Oṣogbo?” Let me tell you. Oṣun-Oṣogbo (O-shoon O-shog-bo) is an annual festival taking place in Nigeria, along the banks of the Oṣun River. Oṣun is actually an Oriṣa, a Goddess of sorts; rivers, fertility and motherhood are her domain. The festival celebrates the people’s gratitude for her and honors her, as she is a chief deity in the Yoruba pantheon. Throughout the episode we follow a handful of Americans who have come to Africa for the festival and be apart of this ancient ceremony that speaks to their spiritual selves. That being said, whoever directed this series did so in such an unimpressive way. It is more than possible that my expectations of the film were nowhere near the goals of the filming crew and writers of PBS- Sacred Journeys. I am definitely not a screenwriter, however I feel that if you are trying to make a tv show about religion, conveying the power practitioners feel is crucial. My main schtick is that throughout my time spent watching this I saw oriṣa worshipers with such fervor and energy and Bruce Fieler(PBS’ on-screen narrator) approached it in a bland way; calm narration, off cue music (ominous in mundane situations, light in more powerful ones), and a general isolation almost between the program and what oriṣa worship was really trying to get at. I feel like the enthusiasm and energy, especially surrounding Oṣun-Oṣogbo, is so key to oriṣa worship, and PBS fell a little flat in trying to capture it.

Religious mixture is very much present in Yoruba tradition. Nigeria in particular is religiously divided between Islam, Christianity, and Oriṣa Worship. Bruce Fieler states, in the film, that a big draw towards the christian church in Nigeria is the sense of community and connections the church gives to worshipers. Apparently the Christian church even goes as far as to promise jobs to those who convert to the faith. In response to this, some oriṣa worshipers have begun to try and build a sense of community within their own practice, to keep followers from leaving their ranks. This is not necessarily hybridity or ‘religious mixing,’ I would say it’s more of an evolutionary process. One faith takes ideas from another faith and grows because of it. I am willing to bet Nigerian Christians take ideas or components from Yoruba tradition, though I do not know for sure.

This evolutionary process extends to the Americas as a mixing of American culture and Yoruba tradition. Paul Johnson has some interesting thoughts on Transculturation (the phenomenon of confluencing cultures) in his book The Study of Religion. “Transculturation nuanced acculturation by insisting that even cultural losses, and the responses to loss, continued to inform the experience of a new territory and generate new practices both among the colonized and the colonizers.”(Johnson 759). Nathaniel Styles goes on to say oriṣa worship is not just ritual practices, it is a way of life. There is an entire culture surrounding oriṣa worship that fosters communities in the United States. It is a way of life that has survived diaspora, slavery, discrimination and many other challenges throughout time. Due to the adversity Yoruba peoples in the New World went through, the Yoruba culture in the United States must be fairly different than the relatively consistent culture of “Yorubaland” (Nigeria). I think it would be pretty interesting if Bruce Fieler and the PBS team interviewed Alathia Stewart and Oni Yipiay-Henton (the two young women undergoing the priestess initiation rites for the Oṣun-Oṣogbo festival in the film) asking them to compare/contrast the oriṣa tradition they grew up practicing, to the oriṣa tradition they were experiencing in Nigeria. This film leaves me with more questions than answers, does the influx of Americans influence the practices of Nigerians? How far have New World traditions deviated from those of old? Does oriṣa practice here in the States reach the same level of intensity witnessed in Lagos? Or are things more subdued due to the influences of christianity and slavery? Food for thought…

Jack Bechtold

Altars of the Black Atlantic

9-22-17

Oṣun-Oṣogbo Festival and the Effect of Slavery on the Yoruba Religion

After watching Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler one can clearly see how the Oṣun-Oṣogbo Festival, and Orisha as a religion itself, is a product of cultural and religious mixing. The roots of Orisha seem to have stayed the same since the beginning, yet all other aspects such as their individual Gods and Goddesses seem to be in constant motion of what is right for the time and place.

The religious mixing was especially clear when reading Thompsons piece “The Concept Altar”. The essay showed how the Africans used their environment and the religions around them to reinforce their own beliefs. At one point in Thompsons book he talks about the fundamentals of the Afro-Atlantic altar – “the fundamentals of the Afro-Atlantic altar are additive, eclectic, non exclusive.” (source). This could not be more true. While slaves, Africans used statues of Christian saints as altars. They didn’t use just any random statue. Worshipers used statues of saints who showed the same strengths as the Orisha they worshiped.

The two American women’s journey to become priestess’s was a great demonstration of the religious mixing because even though they have been separated and forbidden from their religion for hundreds of years, their people managed to endure the prosecution of other religions such as Christianity, Judaism, and Islam by imbibing the differences and celebrating the similarities. A priest in the movie said something to the effect of ‘we are all worshiping the same one God we just have different ways of doing it’. The belief or idea that all of the monotheistic religions of the world are focused on one true god is thought provoking. The different Orisha are simply different characteristics of the one true God. You pray to the specific aspect of god that you need help from. Orisha seems like a very similar form of meditation or communication as Christians practice of speaking to God himself – prayer. Let us say you need help with conception, for example, in the Christian religion you would go to God, or specifically St. Gerard Majella. The same goes for Orisha. If you were having trouble with conception you would have an altar of the Orisha Oshun.

This is a product of the cultural mixing that has been going on since the beginning of time. The Oṣun-Oṣogbo Festival is a great example of the cultural mixing that was a byproduct of the slave trade because people travel from all over the globe to be part of the festival. The only reason that the festival is as big on a global scale as it is is due to the Africans sold as slaves with those of other religious descent. Overall I am in awe at how historical events have caused such a dramatic change in a religion. I wish we could see what would have happened if there was no African Diaspora. Would Orisha still be one of the ten largest religions in the world? We may never know.

Diversity in Diaspora

People from all over the world come to the Oṣun-Oṣogobo festival to celebrate their religion and to celebrate and honor Oṣun, one of the Oriṣas in the Yoruba religion. An Oriṣa is one of the many different aspects of the god that the Yoruba people worship. Oṣun is sometimes referred to as “the good mother” and she has a major role in the story of the world’s creation in Yoruba texts. She is represented by water and the color yellow, and her sacred grove lies in the town of Oṣogbo. The film talks about the spread of the Yoruba religion through the slave trade and the ways African-Americans are reconnecting with their heritage through religion and pilgrimage. At the beginning of the festival there is a tradition in which 16 lamps are lit and people dance and celebrate around them. The film shows a mix of traditionalists, non traditionalists, and people who don’t practice the Yoruba religion dancing around the lamps.

The festival is a good example of African diasporic religion due to all the different people shown attending the festival, and all their different backgrounds. Yoruba religion is practiced all over the world and all the different people who go to the festival show that the religion is not going away anytime soon. At the beginning of the film a man says, “While we may have left Africa, Africa did not leave us.” That quote speaks to the ways people worship and the immense importance of the pilgrimages that people make to Nigeria to reconnect with their roots. The two African American women who are initiated as priestesses during the film talk about rewriting their destinies, and how at the end of the initiation they felt like they were at home. Johnson’s idea of hybridity in African diasporic religions fits some of the women’s experiences growing up. The matching of Catholic saints to different Oriṣas and the different aspects of God found in Christianity and Catholicism speak to the idea of a hybrid sort of religion. While African people were enslaved it was dangerous to practice their religion, and Christianity was forced on them. Instead of giving up their religion, they matched different saints to the different Oriṣas and while they may not have been able to worship and pray in the same way they had, they still worshipped. Thompson did a good job of describing the ways in which the slaves incorporated Christianity into their religion to hide their practices: “…they managed to establish altars to their dead even while blending with the Christian world: they coded their burial mounds as ‘graves’ but studded them with symbolic objects…”(Thompson, Overture: The Concept “Altar”.)

The Oṣun-Oṣogbo festival brings people together, whether they’re practitioners of the religion or not, and to those who are it holds an incredibly special meaning. The vast diversity seen in the people attending the festival shows the ways in which the Yoruba people worship and how aspects of the religion are similar to those of other religions and yet the ways in which they worship are incredibly different. One of the women initiated as a priestess talks about how she tends to pray quietly but that it feels good to pray loudly so her prayers can be heard and how the bells force her to pray loudly. The Oṣun-Oṣogbo festival brings out aspects of African diasporic religions that are beautiful and interesting while showing how the Yoruba peoples’ rituals during the Oṣun-Oṣogbo festival affect the atmosphere in the town and how they affect all the people in the town, whether they are practitioners, traditionalists, non traditionalists, or people who are just there to celebrate Oṣun.

-Hayden

Humanity’s Dedication to the Divine; African Diaspora

The African Diaspora, is a word used to encompass the evolution and adaptation of religious practices originating on the African Continent, that have been held in the hearts of many religious practitioners, dating as far back to the Slave Trade, taking place between 1500-1800. During this period, thousands of Men, Women, and Children were abducted from the African continent, and shipped globally to the “New World”. With them, travelled their intricate religious and cultural practices, and these practices have been subjected to acculturation, and the forced adaptation of slaves to the America’s. The Diaspora, has been subjected to the practices of thousands of people from every walk of life, and have intertwined, culturally, with various religions from the Americas, to produce many blended, or hybridized religions that are continued to be practiced today, in the 21st Century. African Slaves were forbidden to practice African religions once in the America’s and to safely practice their religions, they incorporated the Christian Saints that closely resembled a specific Oriṣa. They “managed to establish altars to their dead even while blending with the Christian world: they coded their burial mounds as ‘graves’ but studded them with symbolic objects…”(Thompson, Overture: The Concept “Altar”). By doing so, they were able to practice their religion safely, and thus beginning the process of hybridization, blending cultural aspects of two religions and creating a hybrid religious practice. In the documentary, “Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler: “Oṣun-Oṣogbo” two American-African women, as they identify, are documented as they participate in the rite of induction into the priestess-hood of the Orisa, a Yoruba word for goddess, Osun.

Alatin Stewart, and Oni Yebiye-Hinton are two young women, traveling to the Oṣun-Osogbo Festival, in Osogbo, Nigeria. They answered the call to become inducted as priestesses into the Yoruba religion, an example of an African religious practice originated on the continent itself. The two young women, until this point had led their lives in the cultural-melting pot of the United States, and are ecstatic to return to the place of their ancestral roots, to dedicate their hearts to a religion that may have even had their ancestors as their religious leaders, many decades ago. The quote “We left Africa, but Africa never left us.” emphasizes the importance of keeping ones religion alive in their hearts, even if, like the African Slaves taken from their homeland, there comes challenges to ones environment, or lives in which their faith, and every other aspect of their being, is tested. When Alatin and One arrive at their religious site, the scene is one of abandoned streets, lined with stray animas, and a large gate at which their religious induction is to begin. Once the gates opened, we are allowed a glimpse into the heart of the Yoruba tradition, with priestesses and priests, welcoming the young women, and many breath-taking altars, lined with sea shells, gorgeous pearl jewelry and vibrant colorful flags to represent the Goddess Oṣun, who is a goddess of water, fertility, beauty, and love. The representation of Altars is a deeply sacred practice in the Yoruba tradition, as the focal point for the channeling of a god, or goddesses energy, and welcoming them to create change in the lives of the practitioner.

The Oṣun-Osogbo Festival, is a perfect example of the African Diaspora, and how various aspects of the cultural perspective can be observed to be similar to other religions such as Christianity. The flags used in the Yoruba tradition, contain multiple colors and patterns to represent different Oriṣa, similar to in Christianity, how various altar cloths and garments worn by religious leaders represent various saints, and angels. The Altars in the documentary are vastly similar to the altars read about in Thompson’s article, expressing different Oriṣa through colors, patterns and the fabric itself used to craft the flags. Thompson expressed the importance of an altar, and how an altar reflects the personality of the practitioner, and how they connect with their Oriṣa. Another cultural similarity are the dressings worn by the Yoruba women, that resemble closely many dresses and pieces of clothing worn by Spanish practitioners of religion, performing ritual dances for their gods and goddesses. These similarities amongst the Yoruba practices and those of other places display the acculturation that has occurred since the Slave Trade, to further adapt religious practices to include practitioners beyond the Yoruban culture.

Tying together with the documentary, the young women, were inducted as High priestesses of Oṣun, and were allowed to enter into Oṣun’s grove, the sacred dwelling place of the goddess of water, beauty, fertility, etc. and the two priestesses stood over the river, and explained that they both felt as if they had returned home, and this is what they were searching for their whole lives. These young women display the nature of the Diaspora, that two young women raised in a different part of the world in a different culture, could travel back to Africa and become High Priestesses, and devote their lives to the path they felt destined to walk. The Diaspora lives in the hearts of people today, who practice their religious beliefs freely, without constriction, in every location of the world, and blended aspects of their beliefs to honor their roots. Their growth and evolution throughout their lives and the life of their beliefs, and how they as people, will continue to grow, evolve and adapt to an ever changing world, just as so many African Slaves adapted and changed the beliefs of Diasporic Religions, to an ever changing global network of divine knowledge and practices.

Into Oṣogbo From An Outside Perspective

The African diaspora is a religion composed of multiple religions and was stripped from its roots during the slave trade. Communities were forced out of their homeland and shipped all over the Americas. The forceful movement of these people stripped individuals of their origins and identity. Two young American women traveled to Oṣogbo to be initiated as priestesses to the goddess Oṣun. Their journey to Oṣogbo brought to life their heritage, “I actually consider myself to be an American African because it wasn’t by choice. So much of our knowledge was taken away, so much of our religious faith was taken away, our names were taken away. We were blank canvases and there is no power in not knowing who you are or not knowing where you come from. This journey, coming back here, means that I’m taking back that power, that I’m taking back that identity and I’m walking in that. I’m walking in who I am” (Eaton). Practitioners of the African diaspora religion tend to focus on the positives of their movement and think in an optimistic view for finding their origin. They find positivity in traveling to Oṣogbo, they notice that their religion and culture has managed to spread all over the world and they still manage to find their way back to their origin.

Oṣogbo is the largest city in Nigeria and is the heart of the African diaspora religion. It is known as Yoruba land and brings thousands of pilgrims every August to the Oṣun-Oṣogbo festival. This festival is in honor of Oṣun who is the African goddess of beauty, love, prosperity, order, and fertility. Worshipers of the Yoruba religion and tourists pack the streets of Oṣogbo learning and joining in on traditions of the African diaspora.

The festival begins with the welcoming of local Orisha. Orisha are spirits that reflect the supreme divinity. Each person practicing the Yoruba religion have their own personal Orisha that they worship. Worshiping one’s Orisha is done with personal offerings and an altar devoted to their spirit. “Her devotion placed her body in spiritual affinity with the ancient image of a woman kneeling before an altar like circle in the area of ancient Djenne, an image dated to the Middle Ages” (Thompson). Prayer and worship to your individual Orisha are very important in the African diaspora religion. Personal altars serve as a divine hope for those who pray to them. Each personal altar is expressed with offerings, dedication, and sacrifice.

As a community, the lighting of an ancient lamp represents the welcoming of Oṣun in the Yoruba kingdom. A significant part of the lighting ceremony is when the King and other political leaders come together to dance around the fire to welcome Oṣun. The presence of the King and political leaders represents the union between political powers and spiritual powers. The significance of the dance around the fire has to do with the importance of dance in the Yoruba religion. Music and dance is a major component in the African diaspora. It is not only an artistic expression but a way to praise the spirits. In the lighting ceremony at the Oṣun-Oṣogbo festival, royalty dance around the fire to represent the union between political powers and spiritual powers.

Privately, priests come together in a sacred ceremony to bless new priests. These newly blessed individuals are asked to give their hair to their Orisha as a way to symbolize all the negative powers leaving and the new growth to be positive and blessed. The Ifá, which is the scripture of the Yoruba people, contains the history, practices, beliefs, and traditions written. Priests foretell the future using the Ifá allowing individuals like the new priests to rewrite their story and pray for the things that they want.

An important site of worship in Oṣogbo is Oṣun’s sacred grove. Many shrines are placed here and it contains the sacred river where many sacrifices are made to Oṣun. A tradition of the African Diaspora religion is to worship history. At Oṣun’s sacred grove in Oṣogbo, Nigeria, it is the origin of Oṣun’s power. This is why during the Oṣun-Oṣogbo festival this grove is the spotlight of worship. Another part of history they worship is their past kings. The ceremony of the crowns involves the crowns of the past 18 kings that have ruled Oṣogbo. Each is blessed by the community and by Oṣun.

An important component of the African diaspora religion is clothing fabrics. It is believed that the patterns and colors of one’s clothes are associated with your Orisha. Those who take part in making the clothing, like those who make indigo clothing, are seen as Oṣun’s disciples. All these traditions give the African diaspora community a sense of engagement in their beliefs. Simple objects like prayer bells bring traditions to life and allow the worshipers to connect with their Orisha. Humans and Orishas are meant to be connected and the Orisha’s goal is to help reinforce humanity’s role that humans and animals thrive and survive.

In all, the African diaspora religion has many traditions and customs. These traditions and customs include a variety of aspects of the gathering of thousands of pilgrims to celebrate the Oṣun-Oṣogbo festival which includes the custom of the King and other political figureheads dancing around the fire at the lighting ceremony. Even the clothing fabrics individuals wear have specific patterns and color that indicate their association with their Orisha. These traditions and customs, and the extent to which worshipers follow and practice them indicate how strongly the religion has survived and thrived since its’ slavery times in which the African diaspora religion was stripped of its’ roots.

Eaton, Leo, and Bruce Feiler. “Osun-Osogobo.” University of Vermont Libraries, Kanopy, 2014

Thompson, Robert Farris. Face of the Gods Art and Altars of African and the African Americas. The Museum for African Art, 1993.

-Louisa D’Amico

A Journey through an African Diaspora Religion

African Diaspora is a term used to describe the mass movement of African culture and religion during the slave trade. During this time, the colonists who were taking away the freedom, names, and lives of the slaves, could not take away their religion and beliefs. Diaspora is the incredible instance in when even though the religion is spread out around the world, people are able to still follow it with their own culture as a part of it. These religion are able to adapt and connect with different cultures, religions, and beliefs. The religion of Yoruba was able to spread to many different areas along the Atlantic Coast during this time and with this came populations who brought their own, new culture to the religion. In the documentary, Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler: “Oṣun-Oṣogbo”, two American girls are followed as they travel to Nigeria in order to become priestesses. This religion is an African Diaspora and this is proven by these two young college students and their travels to Nigeria and a center of Yoruba religion.

The main story follows two students, Alatin Stewart and Oni Yebiye Hinton, and their journey to Osogbo, Nigeria. It starts off with the back streets of the biggest city in Nigeria, which is Lagos. This beginning of the documentary is compelling because the images show a part of town that is run down, dirty and overrun by stray animals. Then, a gate opens for Stewart and Hinton, revealing a beautiful altar and the connective power that this religion holds. Later in the documentary, Stewart and Hinton go to a sacred festival called Oshun-Oshogbo. Oshun is a deity that is associated with water, fertility, love and purity and this festival is to honor her. The main part of the festival is when a young, virgin maid, carries sacrifices to a river front. After this, she is now regarded as a goddess as she leads everyone back. This is an incredible and passionate festival welcome to all. It starts on the streets, where everyone is trying food from different types of people and cultures. One of the most interesting parts about this festival is the sheer number of people who attend that are not African Diaspora followers. The importance of this festival is emphasized by the history of African culture. Africans were pushed out of their land and forced to change religion. As the priest said towards the end of the documentary, “We left Africa, but Africa never left us.” This demonstrates how they spread out over the globe hundreds of years ago, and each year are able to make it back to where their ancestors once lived and celebrate unity.

“Diasporas are social products that must be rehearsed, represented and refreshed; they do not spring up or endure automatically; rather they demand continuous long-enduring effort.” (Johnson, 515) This quote, from an excerpt of “Religions of the African Diaspora” by Paul Christopher Johnson, explains that the African Diaspora religion needs to be constantly practiced to ensure that the long history of the religion is not forgotten. This is shown in the documentary about the Oshun-Oshogbo festival. This festival is done every year and most things about it do not change. These people continue to practice this religion and barely change anything about it. This is in agreement with Johnson because these people keep their religion in mind and make sure that the little aspects and traditions are kept generation after generation. This also demonstrates Johnson’s idea that this religion did not spontaneously arise; it has been worked on since the slave trade to the present day and will continue to grow. This religion will be long lasting due to the accepting nature of its followers. They are not secluded, many followers are also Christian and Muslim and are able to integrate aspects from both religions into their own beliefs. For the reason of world connections and the ability to integrate and change, Yoruba is an African Diaspora Religion.

-Seth Epling

A Slice of African Diaspora Pie

The film Sacred Journeys with Bruce Feiler: “Oṣun-Oṣogbo” shares with us the festival of Oṣun-Oṣogbo, and all of its extraordinary features. The work uses the perspective of both scholars and practitioners to show us what literally and spiritually happens during this event. The festival is a celebration of the Oṣun, the goddess of beauty, love and fertility. It began with the first Yoruba King swearing to protect and honor Oṣun’s grove, and in return Oṣun would bless the all that kept it safe. Now, it is a great gathering of all who follow this indigenous African faith from all around the world to renew this ancient vow.

The African Diaspora is a religion that began in Africa, but has spread throughout the world. Each movement has changed how the original religion is practiced while keeping the same idea. The first reason that this festival is an example of African Diaspora, is because the people who take part in the ceremony come from many different parts of the world. A large portion of non-native folk that attend are from the Americas. This is mostly because the slave trade that took place between the 1500’s and 1800’s brought many of the Yoruba into the Americas. Once in the “New World”, the slaves were prohibited from following any religion from Africa. To get around this rule they, “managed to establish altars to their dead even while blending with the Christian world: they coded their burial mounds as ‘graves’ but studded them with symbolic objects…”(Thompson, Overture: The Concept “Altar”). Other techniques discussed in the film involved associating certain Oriṣa with certain saints, then worshiping those saints. This secret devotion to the Oriṣa kept the religion alive in a variety of forms across the continent, which is why so many people from so many places can come together and celebrate the same Goddess Oṣun. The diversity of the history in each participant is part of why I would consider the Oṣun-Oṣogba festival an example of African Diaspora.

The next reason that this great celebration is part of the African Diaspora is because of the art involved in each item used during the ceremony. The color and pattern of each dress signifies different Oriṣa, and one would wear the colors of the Oriṣa that speak to them. Beyond the colors, the fabric itself is tradition boutique fabric and is typically used during rituals. Other symbols that reflect the African Diaspora are the altars for the different Oriṣa. The altars in the video had lots of similarities some of the altars we read about in Thompson’s article, with each item specific to the altar of the deity it is designed for. The interesting difference between the video and the readings is that no two altars are identical in that each altar is both spiritual and personal. The same holds true with the dresses and art in the festival compared to ceremonious clothing used in the Americas. There are commonalities in which each Oriṣa represent in general, but what each god represents to the individual will vary. The Oṣun-Oṣogbo altars represent the African Diaspora well because they add to the variety ways the same god can by worshiped by many individuals.

The Oṣun-Oṣogbo festival is very representative of the African Diaspora because it is another variety of how the Oriṣa can be worshiped, and how others across the world can still devote themselves the same as those native to Oṣogbo.

Keeping the African Diaspora Alive

In the heat of August, tens of thousands of people crowd the streets of Osogbo, Nigeria where they plan to spend the next 12 days honoring their most important Orisha, the goddess Osun. Osun offers grace to Osogbo and ensures their lives are well as long as the people honor her and her Sacred Grove once a year. The beauty and intensity of this festival is explored by Bruce Feiler in “Osun-Osogbo” an episode of a documentary series called “Sacred Journeys”. Feiler takes you into the heart of Osogbo to show the world how this city honors their goddess from lamp lighting ceremonies to animal sacrifice. After Feiler’s twelve day journey is over and the film has ended it is clear that the Osun-Osogbo festival is an example of the African diaspora with the memories that shape this culture, the distanced covered from a time of exile, and thousands of people returning to Osogbo every year.

The African diaspora is an idea that there are communities around the world that came from descendants of the slaves taken from Africa. Paul Christopher Johnson’s quote from his writing “Religions of the African Diaspora” best connects this idea to the Osun-Osogbo festival, “Diasporic religions are composed on the one hand out of memories about space-places of origins, about the distance traversed from them since a time of exile, and physical or ritual returns…” Two women whose journey of becoming Yoruba priestess’ in the film is the most accurate example on how this festival represents the African diaspora.

The two women who traveled to Osogbo with Bruce Feiler tell him what life was like growing up. They both practiced the same religion depicted in the festival but in the Americas; their only real connection to the Yoruba people was through memories of their families. This example from the film is a key representation of the African diaspora because the Yoruba traditions were kept alive in small communities across the world through memories from their African descendants passed down from generation to generation.

Not only did the women practice their religion from memories passed down, but they understood how their small religious community in the Americas came to be. During the slave trade most slaves came from the coast of Nigeria, bringing their culture with them. The forced journey corresponds with Johnson’s idea of the African diaspora, “…the distance traversed from them since a time of exile…”. This idea made the two soon-to-be Yoruba priestess’ and many others feel the need to come back to the festival to experience what was taken from them and many other generations. Their physical returns due to a past time of exile truly captures the African diaspora in the Osun-Osogbo festival.

While the idea of the African diaspora is not one known to everywhere this is definitely a film worth watching. It is truly amazing to see a culture that has been spread all over the world stay connected through memories, which in turn gives them the desire to return to the heart of their culture, the Osun-Osogbo festival.