The Altar-native Perspective of Afto-Atlantic Religions

Background Information

The concept of aṣe is ever present in the construction and use of Yoruba altars. In order to understand Yoruba art, you have to understand aṣe. Everything has aṣe, it is power, authority, energy, and it is vital. All objects on Yoruba altars have aṣe. Yoruba altars are constructed differently based on which oriṣa they are for, and who makes the altar. The consistency in objects that you may find on Yoruba altars would be the symbols and colors of the god that they are for. Blue and white would be on an altar for Yemoja, as well as symbols of the ocean and twin figures. Yemoja is the mother of the waters, she is associated with salt water, motherhood, children, the full moon, pregnancy, and women. She gave birth to fourteen other oriṣas, leading her to be the protector of children. Altars for her will also sometimes contain symbols of her son, Ṣango, the god of thunder. Yoruba altars can be general or they can be personal, and more often than not they  are personal. There may be objects on an altar that are not traditional or not found on most altars for the oriṣa the altar is for. The oriṣas are not strangers to change, they welcome it, and so if something on an altar is not traditional, the oriṣas have no problem with it.

are personal. There may be objects on an altar that are not traditional or not found on most altars for the oriṣa the altar is for. The oriṣas are not strangers to change, they welcome it, and so if something on an altar is not traditional, the oriṣas have no problem with it.

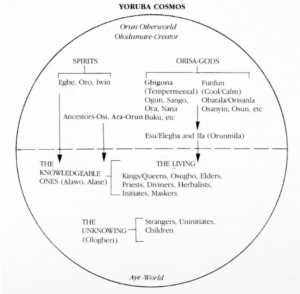

The Yoruba people are a people in southwestern and north-central Nigeria as well as southern and central Benin. During the transatlantic slave trade, many of the slaves that ended up in the Americas and in the Caribbean were Yoruba. The Yoruba religion mixed with Christianity and many oriṣas now have counterparts to Saints. Yemoja’s syncretized counterpart is Our Lady of Regla. Yemonja is linked with the oriṣa Olokun, who represents the bottom of the sea. According to Yoruba myths, Yemonja originated in the Oke Ogun area in Nigeria. She is often portrayed as the wife of different make oriṣas like Obatala and Orisha Oko. Oriṣas are sorted into two groups based on temperament. They are generally organized in the categories of “hot” and “cool/calm.” Yemoja is on the cool/calm side, whereas oriṣas like Ṣango or Ogun are “hot.” According to Yoruba cosmology Yemoja is said to be the mother of Ogun, Ṣango, Oya, Oṣun, Oba, Orisha Oko, Osoosi, and Babalauiye, but she was closest with her son, Ṣango.

The altar for Yemoja in the Fleming Museum is specifically for Yemoja of the One Cowrie Necklace. This Yemoja is specific to Professor Lorand Matory, who created this altar with help from a Yoruba priestess. This Yemoja’s personality reflects Professor Matory’s personality and his personality reflects hers. The altar features many traditional and nontraditional aspects of Yoruba altars.

Some of the nontraditional objects include the photos found on the altar. One of them (1) depicts a priest of Yemoja in Nigeria who commented on Professor Matory’s relationship with his now wife. The photographs represent Professor Matory’s relationship with his Yemoja and his personal history with the people of Yemoja. More traditional objects on the altar are the Ìbeji (3, 22) and the embodiment of Yemoja (25). There are the Ère Ìbejì Ìbẹẹ̀ta, which are triplet statuettes (3) and then there are the Ère Ìbejì, the twin figures (22). It is said that Yemoja took in the Ìbejì and raised them. In Yoruba culture, twins are special and viewed as magical, the Ìbejì represent motherhood and the protection of children on this altar. The embodiment of Yemoja, found in the middle of the altar, shows Yemoja as a mermaid within a large calabash vessel. Yemoja is usually depicted as a double-tailed mermaid due to her association with the river Ogun and with salt water. The river stone (27), is another water symbol to help bring Yemoja’s presence to the altar along with all the other objects.

Objects described in the item catalog are marked with numbers that correspond with the diagram of the altar shown above.

Another somewhat nontraditional object on the altar is a blue candle (11). Traditionally, lanterns are used, however, the lanterns are usually small earthenware dishes with a kind of mouth with a cotton wick sticking out, and when they’re lit they create a lot of smoke. The replacement of the lantern with the candle is an example of syncretism in African diasporic religions. The type of candle found on the altar is a kind of “safety” candle usually found in churches. It is also borrowed from Latin American traditions in religions like Santeria and Candomblé.

Although the altar is primarily for Yemoja, there are objects for Ṣango, Yemoja’s son, found on the altar. In Yoruba mythology, Yemoja was very close with her son Ṣango. He is honored on this altar with pink beads around the blue candle (11), a thunder staff (9), and the Aso Oke beneath all of the objects on the altar (28). Worship of Ṣango is often overlapped with the worship of Yemoja due to the familial connection between them.

It is not just aṣe that makes altars work, it is also the objects on them. Altars for Yemoja will have twin figures, water symbols, symbols of motherhood, and things that she likes, such as gin. Altars may be elaborate but they can also be simple. It is not how big or how extravagant an altar is that makes it work. Yoruba art is never created with the “art for art’s sake” mindset, it is always created with a mindset of “art for life’s sake.” Art is always created with a purpose and that purpose is part of the aṣe that the object has.

Yoruba altars are not usually constructed for museum exhibits. Putting them on display for others generally takes them out of cultural context and into a setting where they can be harder to understand. The altars are used to worship oriṣas and to communicate with them. The art on them is for the oriṣas and shows which oriṣa the altar is for. The objects are usually activated through their arrangement on the altar, ritual, food, water, and light. Once charged with aṣe, Yemoja can be called to and worshipped. The power of Yoruba art and the aṣe in the objects on the altar can bring an oriṣa’s presence to the altar where worshipers can personally connect with them and speak with them.

Purpose of Altar

One of 4 featured altars in the Fleming Museum’s “Spirited Things” exhibition, the Yoruba Altar is a demonstration of artful creation rooted in complex faith. A quick scan of the Altar and its entirety is not nearly enough to appreciate the multifaceted nature of its wood, bronze, and cloth pieces. The vibrant colors and awe-inspiring mechanisms of the Altar suggest that it is a product of uncanny devotion. First, to understand the Yoruba Altar as an involved construction within the museum, the general concept of altars must be explored.

If you questioned an individual fostered in western culture about what an altar meant to them, they may reply with a comparison to an Indiana Jones movie or even a shrine of some sort. In reality, an altar is an approach to practicing religion through material objects. An outsider may be able to determine that altars are visual representations, however, the same lesson that denotes judging a book by its cover can be applied in this case. There is much more evident than the eye can see regarding the objects on an altar due to the fact that each one works in a specific way that satisfies a universal condition or higher power within a religion.

In light of this, Thompson detailed altars as essential sites of ritual communication where the boundary between the spiritual and tangible world is connected. These sites contain high concentrations of spirituality, where each piece has been thoughtfully selected according to its symbolic representation (Thompson, 1995, p. 26,50). For example, the Yoruba altar features items that can be tied to specific gods and goddesses as well as experiences that have resulted from a lifestyle centered around Afro-Atlantic orisa worship. Material dedications that enable followers to express their faith are less present in a western scope of religion. Acknowledging that materiality is not an inferior mode of religious practice ensures a just approach to the study of orisa worship. Once this principle idea is understood, one can accurately get a sense of the Yoruba Altar’s reasoning.

“Yoruba and other Kwa-language groups in West Africa define their traditional altars as the “face” or countenance of the gods” (Thompson, 1995, p. 28). Exploring this notion, Yoruba altars are constructs of facial pathways to enable communication with the spiritual world. The Yoruba Altar is no exception to this notion as it specifically provides a “face” for the goddess of the river Ogun, Yemoja. Yemoja can be viewed as the most central and elevated object on the Altar (15), and her presence is summoned by many items within the prominent white calabash. These items include cowrie shells, clam shells, kola nuts, river stones, and a mermaid figure. The Yoruba Altar, in particular, invokes a specific embodiment of Yemoja, Yemoja Olowo Kan, “Yemoja-of-the-One-Cowry-Necklace”. This embodiment of the goddess was birthed in 2014 through ritually charged contents that had been part of other Yemoja altars in Nigerian Yorubaland.

In addition to the Yemoja associated objects on the Altar, other objects relevant to the goddess and Afro-Atlantic religion were chosen to be incorporated too. For instance, a wooden staff (9) that resembles a double-headed axe represents the spirit of Shango. Shango is the god of thunder and lightning who also happens to be Yemoja’s son. The red rolls of cloth placed on either side of the Yemoja embodiment (14) as well as a red and pink beaded necklace surrounding a candle (11) are also indications of the presence of Shango. The most obvious hint of Shango’s relation to the Altar is the color red. The god of twins, Ibeji, is also referenced on the Altar through numerous twin figurines (3, 22) which serve as commemorates of deceased human twins. These gods along with the relation of the river goddess Osun amongst objects comprised of brass (24, 23) suggest that the Yoruba Altar serves to honor multiple deities in orisa faith.

The Yoruba Altar is an expression of devotion to the gods and goddesses of orisa religious practices that are of great worth. Professor Matory of Cultural Anthropology and African and African American Studies at Duke University is responsible for the creation of the Altar. The Professor has selected objects that are common to most Yoruba altars, however, the photographs (1, 2, 12, 25) are a relative abnormality. The Professor explained that these photos serve as a symbol of an emotional connection to the experiences he has had with the people who worship the goddess Yemoja. These photos remind him of his engagement with orisa worshippers who he worked with when he resided in West African Yorubaland. These people have led dedicated lifestyles to fulfill the dutiful obligations that are expected of them in the worship of the orisa. The Professor also considers the altar to be his own Yemoja, as his personality reflects the personality of the goddess. The Yoruba Altar in this view is an authentic medium to acknowledge the relationship the Professor and his counterparts have formed with the orisa, chiefly Yemoja.

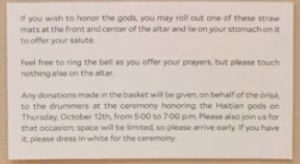

Important to note is that the Yoruba Altar is on display in the context of the museum, where observers are encouraged to roll out straw mats at the front of the altar to offer their salute to it. While the Yoruba Altar is a devotion to several orisas and a personal expression to them, it is also a public representation that enables individuals of all backgrounds to offer their prayers. The Yoruba Altar is an active pathway for all to encounter the boundary between the physical and spiritual world. Cultural qualities such as sacred twin-ship, orisa presence, and personal authenticity are all included in the display of the Yoruba Altar. Unless you were looking for them, these aspects of Afro-Atlantic religion would be missed without a proper analyzation of the complex pieces found on the Altar.

Item Catalog

(Objects 1, 2, 12, 25) Photographs– Photographs of past family members are present on altars to bring about ancestral spirits. Altars are largely about communicating with past departed family as well as spiritual worship, with this being said photographs of family members and important people bring their energy to the altar so they can be present in ritual.

3.) Statuettes of Triplets (Ère Ìbejì Ìbẹẹ̀ta)– Three figures crafted of wood and adorned with pigment and beaded jewelry. They are thought to be triplets (2 boys, 1 girl). Figures are protected by Shango and are placed on the altar for deceased twins (or for orisa of twins). The actual figures themselves are cared for like children because they honor living or deceased twins.

4.) Yoruba House of the Head (Ile Ori) with Ori – A house visual/headdress made of leather, white handwoven cloth (kijipa), blue handwoven cloth (kijipa), and red cloth studded with cowries, mirrors and one red tubular bead. The object is a physical representation of the Inner Head of its owner. An owner would pray to this object for good fortune and occasionally sacrifice animals to it. Present on the altar because it represents integral qualities of Yoruba culture.

5.) / 19.) Silver Fans (Abebe) – The decorative fans called Abebes made of composite wood and sheet metal. Contains images of two fish and an abstract woman carrying a calabash on her head. The Abebe symbolizes the goddess Yemoja’s cooling nature. The female figure on the Abebe represents a possession priestess of the goddess. Present on the altar because it is symbolic of Yemoja.

7. Yoruba Terra Cotta Water Vessel for Sacred Altar: made out of stone and terracotta, this vessel is placed to the left side of the altar. It is elevated a few inches above the surface by a red fabric at the base. The vessel has a white cloth draped over the opening on top and wrapped at just below the lid. This vessel is used to provide a water offering to the Orisha Yemoja.

8.) Cowry Shell fan – The front face of the fan is decorated with cowry shells and made of a woody material. Cowry shells are present for the Ère Ìbejì and Yemoja. This object is placed with the cowry shells faced up at the front of the altar close to the triplet figures.

9.) (Oṣé Ṣàngó) Double-Axe/sceptre, Dedicated to the God Ṣàngó – A wand with a double axe on the top made of pigment and wood, carried by possessed priests and priestesses. Present on the altar because it serves as an emblem of the thunder god Shango, who is Yemoja’s son.

10.) / 15.) Yemoja. Goddess of the River Ogun – Individual objects that make up the visual: white cloth, an iron casted mermaid figure, a large calabash vessel painted with river lime (efun), cowrie and kola nut shells inside the vessel, a necklace surrounding the vessel. This embodiment of Yemoja personalized for an owner is given sacrifices and directed prayers in return for the goddess Yemoja’s blessings and protection. “The goddess asked for her approval of the items assembled in the creation of this embodiment of her” Present because the altar is for Yemoja, or rather a devotion to Yemoja (this assemblage of objects is the focal point of the altar).

11.) Blue candle– The blue candle on the altar is symbolic of the water deity Yemoja. Looking online, the candle is supposed to be burned over several days. In prior years lanterns were used, which gives light to the goddess during her special periods. Candles are now used instead of lanterns due to modernization. The pink and red beaded necklace is placed at the base of a blue candle inside a white bowl. The necklace embodies Yemojas son Sango.

13.) Brown blue and white Earthenware vessel

This object is a brown pot with white and blue dots on it. There is a lid on the pot and there’s some white streaks that give the front a wispy, feathery look. There’s a blue ring around the area right below the lid and a white ring on the edge of the lid. Kola nuts, the sacrifice of a chicken, guinea fowl, duck feathers.

14.) Red rolled fabrics (Aso Oke) are placed equally on the altar. Both are placed on the inside of the Abebe on either side of the stool for Orisha. Blue and white stripes are shown on the Aso Oke.

16.) Stool for orisa – A rectangular stool made of wood with figures on all four sides bolstering the top of the stool, used to prop both male and female orisa. Important to note that the heads of the figures are enlarged to emphasize the divinity of the object. Present on the altar because it serves as a platform for the orisa-affiliated object to be worshipped.

17.) Yoruba sacred vessel – A head shaped pot made of pigment, once painted red, white, and blue pigments (pigments of camwood are related to Osun). The surface is decorated with marks (finfin) as well. The vessel contains cowry shells, stones, and water from the Ogun river. The vessel could have been used to carry water from the river to the shrine during festivals. Present on the altar because the Ogun river is closely tied with the goddess Yemoja.

18.) Bottle of Gin: A third of a bottle of Gordon’s gin placed slightly off-centered in the back row of the altar. –”used in prayers for longevity because it never decays and in pursuit of communion with the ancestors because the elders have long consumed it.”

20. Yoruba Beaded Bottle: constructed out of glass, cloth, string, and wood this beaded bottle is used in rituals for libations and elixirs. The beading covering the entire bottle suggests that it belongs to a high-status priest. The colors of the glass beads are to represent Yemoja (blue and white) and Sango (red and white).

21.) Opa Osun – Tall rusted object right of the altar, away from the center. Represents the fate of the person and is placed in front of one’s home. Strictly thought to never lie this object down while the person in possession of the object is alive. The object is given offerings and kept upright in order to preserve and enrich the life of its owner.

22.) Twin Figurine (Ere Ibeji) – A wooden carved figure with an accumulation of camwood powder (Osun relation), as well as indigo dye and beaded necklaces (where each bead is symbolic). Twins are highly emphasized in Yoruba culture, therefore if one twin becomes deceased in real life, the proper treatment of this figure will ensure the safety of the other living twin (both twins share one soul). This figure is bathed and fed as if it were the living twin.

22.) Yoruba Twin Sculpture (Ère Ìbejì ) (indigo painted head) – A wooden carved figure with an indigo painted head adorned with a beaded necklace of palm and nutshells around its waist. Iron nails on the figure represent pupils and an aluminum bangle is found on the left wrist of the figure. In Yoruba culture twins are accented and treated with care, therefore if a twin in real life becomes deceased, the proper treatment of this figure will ensure the safety of the other living twin (both twins share one soul). This figure is bathed and fed as if it were the living twin.

23.) Ààja Òsun dídà (a netted bell) – This bell made of bronze is used for Osun. Its placement on an altar suggests it is used to activate certain guiding forces (ase) surrounding the altar or Osun. Present because it enables interactivity with the altar.

24.) Brass Calabash: This brass spherical vessel is placed on the far right side of the altar next to the Ère Ìbejì and the Opa Osun. This vessel is known to invoke the river goddess Osun into the altar.

26.) White plate with figurine

A figurine sits on a piece of cloth in an earthenware bowl set on a white plate. There is money on the rim of the plate. Offerings are asked for the goddess Yemoja represented by the white figurine.

27.) River stone– The smooth white river stone on the altar is symbolic of the water deity Yemoja, mother of the deities. The river stone brings Yemoja’s presence to the altar in the form of symbols. One can charge the river stone with áse to further bring about her presence. The river stone ultimately serves to bring Yemoja to the altar alongside the rest of her objects.

28.) Red Green Orange Purple Blue woven cloth called an Aso Oke on top of the surface that the objects are placed on. Finge at the ends of the Aso Oke. Unique sewn patterns, squares of green orange and red sewn in stands and repeated on the Aso Oke. Colors represent Sango. Aso Oke is a woven cloth in a style that is commonly worn by members of ogboni society.

29.) Indigo Batik: Hanging high above the altar and about the same width of the altar is an Indigo Batik. Square boxes of unique patterns called the Ibadan dun were sewn together to create the large batik. The batik is hung high and is let fall to the ground at the sides. At the top, it is draped into half circle figures over the center of the altar.

30.) Money basket-Money baskets are put onto altars to pay respect to orisa, giving them a direct gift from yourself. Often money baskets are filled near altars because those who worship want to pay respects and be blessed by their deities.

31.) Silver Bell

The base is elevated by a piece of brown fabric and is rounded and wide. It gets thinner toward the end of the object, which is kind of flat and triangular. The bell is rung during prayer in front of the altar.

32.) Straw mat in front of the altar – This mat is placed and rolled out in front of the altar already. Sides of this mat are fringed and on the mat lays a straw basket for money offerings and the Ààja Òsun dídà (a netted bell). This mat asks for those who want to step on it for them to take off their shoes before they do so.

Straw Mat (picture is shown below) – Two mats placed off to the side of the altar. For personal use. If one as a desired to do so, they may lay the mat or mats out at the front and center of the altar. With these mats, one may lay on their stomach and offer a salute.

Account for The Layout

The Yoruba Altar dedicated to the orisa, Yemoja. In the center of the altar the stool for orisa that holds a large calabash vessel containing an iron mermaid figurine and cowrie and kola nut shells. This figurine represents Yemoja who is the goddess of the River Ogun. The necklace surrounding the vessel is an embodiment of Yemoja which is given by the private owner as a way to ask the goddess for her approval of the items assembled in the altar which embodies her. These objects all together make the highest part of the altar which represents its devotion to the goddess Yemoja. When worshiping Yemoja, her son Sango is frequently expressed in her dedicated altars.

The eye-catching indigo dyed batik cloth and colorful woven cloth on the stand is representative of Yemojas son Sango. The cloth called an Aso oke is woven in the colors of Sango which are red, green, orange, purple, and blue. The batik illustrates the pattern of Ibadan dun in Sango’s color blue. The pink and red beaded necklace at the base of the candle is the embodiment of Sango while the blue candle is symbolic of Yemoja the water deity, in prior years lanterns were but due to modernization candles have been used instead.

The eye-catching blue quilt and colorful tablecloth on the stand is representative of Yemojas son Sango. Sango’s colors are red, green, orange, purple, and blue which are illustrated in the two cloths. The pink and red beaded necklace at the base of the candle is the embodiment of Sango while the blue candle is symbolic of Yemoja the water deity. In prior years lanterns were used but due to modernization, they have been replaced with candles.

The candle’s placement in the altar is to the front and center allowing those who want to worship the shrine may have easy access to the objects given to interact with the altar. Like the candle, the Ààja Òsun dídà or the netted bell placed at the front of the altar suggests that it is used to activate ase while worshiping the altar. Situated next to the candle is the Oṣé Ṣàngó or the double scepter dedicated to the God Sango. Possessed priests and priestesses carry this scepter. The Oṣé Ṣàngó plays an active role in the worshiping of Sango and Yemojam, which is represented in its placement in this altar. The scepter is placed directly in front of the stool for Orisa and offered for individuals to carry during worship.

The two straw mats on the side and in front of the altar are also placed in such a way that allows for individuals to feel welcome to worship this Yoruba shrine. A silver bell is played flat on the front mat next to a basket where money can be offered and is used actively by worshipers. The river stone placed to the far right side of the altar is also an active piece of the altar. This smooth white river stone brings Yemojas presence to the altar and can be charged with ase by the worshiper to bring her presence to the altar further. Specific items like those mentioned before have a place on the altar easily accessible due to their involvement in worshipping Yemoja. Though the bottle of Gin is placed at the back of the altar and not as accessible as other offerings, the bottle is presented as an offering to the goddess. Gordon’s gin is used in prayers for longevity. This is because it is seen never to decay and represents ancestors because they have consumed it long ago.

Balance is represented in the layout of this altar. On either side of the center stool for orisa, there are identical rolled red fabrics called aso oke and similar silver fans called Abebe. On the left of the stool for Orisa is the larger Abebe and on the right is a smaller Abebe. Both are decorated with images of two fish and an abstract woman carrying a calabash on her head. These are symbols of Yemojas cooling nature and her possession of her priestess.

There are also calabashes on each side of the stool that holds the balance of the altar. On the left side is a brown pot decorated with blue and white dots. This calabash is also decorated with offerings of coal, nuts, sacrificial chicken, guinea fowl and duck feathers. On the right side balancing out the previous calabash is the Yoruba sacred vessel. This pot is shaped like a head once painted with red, white, and blue pigments; its surface decorated with marks which were made to represent a face. Contained in the vessel are cowry shells and stones and water for the river Ogun. These offerings signify Yemoja and her involvement as the goddess of the river. This particular vessel could be used to carry water from the river to the shrine to pour as an offering during festivals like Osun-Osogbo, its active involvement as an offering piece is also a reason why this vessel has a place at the front of the altar.

The statuettes of Triplets and the Twin figurines called Ère Ìbejì are balanced on either side of the altar. The triplets are kept together on the far left-hand side of the stool for orisa. These three figurines consisting of two boys and one girl are figurines that are protected by Yemojas son, Shango. These are seen to be very significant and must be cared for as children. These statuettes are not the center of the altar like the shrine to Yemoja but are still seen as objects needing caring for due to their symbolic representations. On the far right side away from the triplets are the twin figurines. These like the triplets are not presented as the center of the altar but are highly emphasized as to ensure safety between the two which is why they must be placed together. These figures are bathed and fed as if they were living similar to the triplets on the opposite side of the altar.

The Ile Ori or Yoruba House of the Head placed on the far left side of the altar but is considered a significant piece. Its visual symbolism is a house made of leather, kijipa (handwoven cloth), cowrie shells, and mirrors. It is a physical representation of the owners inner head. Owners of this object will pray directly to it and offer animal sacrifices to ask for good fortune. Its position on the altar is farthest to the left of the stool of orisa but is equally as important. Just as important as these two objects are the Opa Osun. This item sits farthest right from the center but is worthy of attention. The tall rusted object is depicted as the fate of the owner. It is strictly thought never to lie it on its side while the person in possession of the object is alive. Just as the stool of Orisa is presented with offerings to keep Yemoja happy and content, this object is given offerings and kept upright to preserve and enrich the life of the one in possession.

The creator of the altar, Professor Matory contributed personal photographs to the altar dedicated to Yemoja. The orisa of his head is the goddess Yemoja. Therefore he found it significant to include his objects that represent who Yemoja is to him. The family members and influential people or places are shown in the pictures and bring energy to the altar so a ritual can be given. These four photographs were placed throughout the altar. The pictures visualizing a door to a Yemoja shrine and the outside window of his house where he made connections with the Yemoja priests are placed by the Ile Ori representing that Yemoja is his orisa of his head. The other two photos depict essential people that have brought him to the place that he is now.

The assembly of objects on the Yoruba altar is significant in the way that the altar works and its interpretation. Certain aspects of the altar like how the vessel of Yemoja is the center and highest portion of the altar determines the overall meaning. If this vessel were moved to the far left and placed lower on the table, it would shift the purpose of the creation of this altar. Each object dedicated to the altar is just as important as its placement on the altar. Objects are made and picked to satisfy the Orisha assigned to them. As each object is placed on the altar, its function and use in worship are taken into account to determine where its placement will be most significant and valued by the Orisha of the altar. Together all objects work together and are correlated with each other to satisfy the purpose of the altar.

Reflection

On the first day of class, I tried to look at the different religions we were studying holistically. Trying to define every object with its meaning, and trying to match that meaning to the overarching, main idea of the religion. This proved overwhelming and not very useful as there was a depth to the Diaspora that I could not yet comprehend. The class lined up, to a strangely perfect degree, with an anthropology lesson which introduced the concept of ethnography, understanding a culture from the perspective of the culture, not my own. This made sense; I had been looking at the culture from a strict, personal definition of religion. I also wrote down in my notes from that class to strictly pay attention to the interactions people had with their surroundings, as they will tell you more about the culture than looking over the culture with a bird’s eye view.

As the class progressed, I eventually began to adopt this attitude. I tried to put myself into the religion, connecting ideas and practices within the religion to some of the practices I perform every day. As Professor Brennan continued to talk about objects and altars, I could then see the importance they played in the religion. The object is an extension, a symbol of something in somebody’s life. An object can encompass so much past, present, and future that only the owner of the object could tell you how much it means to them. Objects are deeply personal artifacts that encompass entire pieces of one’s life. We see the surface of what the object is, but not the extent to what it means. Studying the religion from the perspective of those artifacts helped me realize that there was no “main” idea of the religion, but spiritual connection through symbols, something that everyone does daily.

Contrasting with the uniqueness of the objects is also their practicality. While objects hold unique personal meanings to their owners, they can also portray the same thing across the entire religion. Every practitioner of Yoruba religions most likely possess some of the same objects which signify a certain deity or aspect of that deity. It is through this similar use of the same object that deities are recognized and symbolized on an altar universally throughout the religion. This creates a pattern like aspect to the altar which gives the ritual process order.

The artifacts owned and worship by Professor J. Lorand Matory held a purpose similar to my playlists or CDS, they held personal meaning, memories, and were with me through new experiences as well. They are how I reflect and how I think many times during the day, and I am constantly adding on to the collections of music as well. With this being said, objects are kept with care and hopefully passed down through generations, they accumulate meaning and further culminate in a piece of the owner’s soul. Who or what they signify will always be present if the object is present.

The altar, on the other hand, was trickier to understand, however studying religion from their importance helped me understand they were a catalyst for connection. The altar is a stage that presents the objects in a way which connects someone to spirits. The spatial display and collective importance incorporated into the altar creates a platform for a human and spirit to interact in an energetically charged atmosphere. However, it is not necessarily a man-made, built creation. An altar can be an ocean or a river, for instance in Thompson’s “Face of The Gods” he explains how an altar for the goddess of the sea, Yemoja, can be a naturally formed river such as the Ogun River in Nigeria. The stones and water create the image of the goddess, capturing her attributes and focusing them into a space of worship; a place to present symbols and connect to the spirits which they summon.(PG 270)

The materiality of African Diaspora ended up changing my definition of religion indefinitely. Religion does not have to hold any definition other than whatever connects one to a higher level of understanding and clarity. Through this class, I have begun to understand that religion can be an ongoing way of life, a way of living which aids a person in understanding themselves and their universe. The focus on objects and symbols in these religions constructed the idea that they meant as much as they symbolized to the culture. An object can symbolize levels of authority, power, or even community in which the symbolism they hold is personal but also connects the community together through mutual knowledge. However, the object combined with the altar took them to a place of healing, reflection, and purpose. Religion does not have to be defined or scheduled, but a practice in which one finds understanding and beauty. A personal religion may be different in practices and ideas, but the intrinsic mechanisms behind them are similar.

References