Greg, Tessa, Alyssa, Reshma, Joe

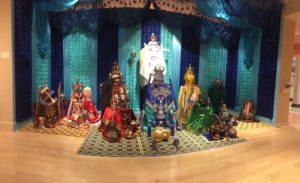

Haitian Vodou Altar

Vodou is a Haitian creole word that describes an official religion of Haiti that contains bits of Roman Catholicism within its belief system. Vodou was creolized and forged by Dahomean, Kongo, Yoruba, and other African ethnic group descendents. These African ethnic groups had been enslaved and brought to modern-day Haiti, then called Saint Domingue, and were christianized by missionaries of Roman Catholicism in the 16th and 17th centuries. The word “Vodou” means spirit or deity within the Fon language of the African Kingdom Dahomey, of where most early practitioners originated from.

Vodou’s fundamental principle is that everything possesses a spirit, and its primary goal/ activity is to offer prayers and devotional rites directed at God, and various spirits in return for health, protection, happiness, etc. During many of these rites, two very important parts to these rituals, are Spirit Possession, and the energy, or “spirit” from the Altar which is used during rituals. Spirit Possession is used to invite a god, or god(s), called “Iwa” into the vessel of the possessed, to do work within the ritual, usually by dancing and inviting the energy of the divine into the ritual. Along with the important concept of possession, the altar is a center for energy and intent. Altars within Vodou have objects placed on them to collect energy, and use that energy within rituals. Objects placed on an Altar can range from a loved one’s perfume to bring their energy into a ritual, an object belonging to a loved one, a statue made in the like-lines of a god to ask for their assistance, crystals, jewelry, etc.

Vodou has been largely syncretized, or has had other religious beliefs blended into it, such as many beliefs from Roman Catholicism, such as the concept of the Altar. Within Roman Catholicism, the altar is a sacred space designated to worship God, and his saints by placing his “body and blood” on the altar and blessing it. Similarly, within Vodou, the altar is used to hold objects such as statues to the gods that invoke and channel the energy to call upon the divine. Catholicism, within its altars, show the history of the religion by showing the life of Jesus Christ, and the history of the development of the religion such as words from the apostles, biblical tales of Jesus’s Humanity, chalices to resemble the one Jesus Christ used at the last supper, etc. Vodou and Catholicism both share the similar aspect of the Altar, however what makes the Vodou Altar at the Fleming Museum unique and distinctly of the Vodou tradition, is the blending of both objects that sanctify the gods, such as the Paket bottles for Ezili Danto, and the inclusion of objects that, like Catholicism, embrace the history of the religion, and where it sprouted from. The Vodou altar displays various objects that tell the story of how it was started, and how it became what it is today.

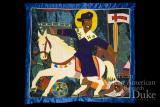

For example, how the altar reflects aspects of the Haitian Revolution within its symbolism, within the Flag of St. Jacques, one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution whom is honored on the Altar. Ezili Danto, is also represented within the altar as a flag, and she was also considered a catalyst for the Haitian Revolution by dancing in the “head” of the priestess Cecile Fatiman on a night in 1791. Also, there exists some cross referencing between the historical references within the Altar, to its correlation of the spiritual purposes of the Altar’s persona and the objects on it. For example, how the Petwo and Rada spirits, “angry and calm” spirits, are on two representational sides of the altar, can also be interpreted as the energy of the slaves imprisoned during the Slave Trade, and how angry, vengeful, and “hot” they would be considered, and how the spirits were relieved of their pain and suffering in Death after they passed, before the end of the slave trade, and how some spirits had passed away physically due to brutality, or imprisonment during the Slave Trade, and even during the Revolution.

Purpose:

An altar is a place where ritual and sacrifice take place. It is where spiritual work and witchcraft are performed, and is considered the center of one’s religious life. The purpose of this altar is to act as a center of worship and offering to various Hatian gods and spirits (Iwa). The various Iwa are able to influence different aspects of Hatian life – practitioners aim to keep the Iwa happy, therefore altars such as this one are constructed to be used as places to make regular service to the Iwa. This altar was created with items from Professor J. Lorand Matory’s personal collection, and was assembled by various curators at the Fleming Museum.

A typical Hatian Vodou service begins with a recitation of prayers and songs in French, and then a litany in Hatian Creole and Langaj that goes through all the saints honored by the house/venue, followed by a series of verses for the main spirits being honored. As the songs are sung, spirits come and visit the ceremony, often taking possession of individuals and speaking through them. Drumming and dancing are also vital parts of Vodou rituals. These rituals typically take place at the altar sites, with the objects acting as connections to the Iwa. For example, the Paket Kongo that appears on the altar (boat with rainbow string of wrapped around stem) is dedicated to Papa Loko. Papa Loko is considered the founder of all priests, and the guardian of the deepest secrets in Hatian Vodou. Loko is so powerful that he never makes an appearance through possession–his power and being are too supreme for humans to face. Papa Loko is also a doctor, so practitioners might pray to him through song and recitation at this altar to ask for good health and a cure for any ailments. Papa Loko’s power is known by all in the world of Vodou, so he is a popular and well-known deity to offer service and worship to at Vodou altars.

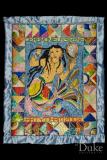

Another example of a ritual that might take place could be the ritual purpose of the colorful flag depicting Lasiren, the queen of the ocean. Lasiren is an Iwa of wealth, and owns all the riches of the sea. A flag showing an artistic representation of Lasiren is shown as a part of this altar in order to please her and show that practitioners are hopeful that through ritual, she will watch over them and guide them to wealth and prosperity. Her flag is adorned with bright colors and sequins, proudly on display on the wall above the altar in hopes to please the goddess of wealth with beauty and extravagance, encapsulating the idea of luxury she is said to stand for.

Macoute Shoulder Bag for Vodou God Azaka – straw bag with red string holding it together, with red, blue and straw tassels.

Paket Kongo for Grann Marie Bossou – Blue and red ribbon base with two blue structured ribbon arms out the side. Red, blue and black feathers come out of the top. This is meant to be a portrayal of lwa Grann Marie Bossou, who is sympathetic to and helps out those who have been betrayed.

Paket Kongo for Ezili Freda – Red string cloth base with white stem and green and red feathers at the top. It acts as a representation of Ezili Freda, god of wealth, love and coquetry.

Paket Kongo for Ezili Danto – Rainbow of string wrapped around stem, with red and yellow feathers on top, green string around the base with a blue string heart at the top of the base. Embodiment of Ezili Danto, the protector of children.

Bottle for Ezili Freda – gold sequin bottle with black sequin heart in center filled with red, blue, pink, and grey sequin squares. This bottle would be placed on an altar for Ezili Freda filled with rum and spices that the Iwa prefer.

Haitian flag – small ~5×7 in. Haitian flag, there to represent the heritage and spirit of the haitian vodou religion

Rèn Congo- the base wrapped in pink silk ribbon, wrapped by green satin cloth. The green cloth is beaded green and pink with peacock feathers extending out from the top. Arms extend out from the base wrapped in pink satin ribbon.

This object is placed here to represent the Queen of the Kongo, the Iwa of knowledge and good luck. Once the Pakét Congo is activated it has the ability to talk back to whoever may be worshiping. The body resembles that of a women and the peacock feathers represent the crown of the queen.

Bottle of Florida Water – used in rituals within Vodoun. In front of the Ren Cong, so most likely offering to the Queen of Kongo.

Bottle for the Haitian Vodou Lwa Bossou- Decorated with cloth covered by sequins and beads that for the shape of a bull’s head. Bossou is the bull god of the Haitian religion. The bottle will be filled with a specific kind of liquor and spices. During rituals the person possessed by Lwa is the only one who can handle the strength of drinking what’s in the bottle.

Lwa Kafou- box shaped structure covered in black and red cloth. There is a crucifix as well as a spoon and fork arranged on top. Kalfou is the god of the crossroads. Kalfou is the counterpart to Legba in the Petwo nation. He can be associated with fighting and making war. He allows people to cross over, between the world of the living or the world of the dead, as well as deny them too.

Flag For Ezili Dantó- Green flag covered in detailed beading showing a mother and a daughter figure. Ezili Danto represents the single mother figure. She defends her children and also gives them strength. She can be seen as aggressive and fierce but all to protect her children.

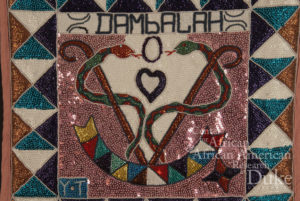

Dambalah Flag- Dusty rose colored fabric with triangles in the form of squares on the border. Two green and red snakes coiled around two red croziers and between them is an outlines heart. This represents Iwa Dambalah. The snakes represent the love between him and his wife. He can be known as the snake divinity.

Colorful Handkerchiefs – each handkerchief is a solid color that is hung on the front of the altar. Each color represents a god. The red for example represents Kalfou. During possession the handkerchief of the god who is possessing the person will be wrapped around the person.

Coca-Cola Bottle- this bottle is here an an offering to Kalfou. He likes coke therefore this bottle is here to please him.

Bacardi- this liquor is here as an offering to (what Iwa is represented behind bottle). This is his favorite therefore this is what is offered to him.

True Grenadine- also here as an offering to the Iwa. It is meant to keep them happy and satisfied.

Anisette- another liquid that is being placed her to be used as an offering to the Iwas. This is again meant to keep them happy in the hopes of not angering them. Which in turn would cause trouble.

Flag of Ogou/St. Jacques: This flag depicts Saint Jacques/Ogou on a horse with a man lying on the ground, and other people in the background that seem to be ready to fight. Ogou is a warrior spirit. Such flags are made as gifts to the Iwa.

Bottle for Bawon Samdi: This bottle is purple and covered in black and lavender sequins with a picture of Bawon Samdi, a spirit associated with death and fertility. They work to remind worshipers to live live with exuberance. This bottle is a tribute to Bawon Samdi, in order to keeo him happy.

Haitian Sacred Rattle (Asson) with Snake Bones: This rattle is made of medium brown wood and has a bead covering on it that makes noise when shaken. This is used in a ritual setting, but does not belong to a specific Iwa.

Bottle for the God Kwiminèl: This bottle is wide, red, and decorated with red and blue sequins. Kwiminel is a divinity known for its combination of eros and thanatos. Kwunubek is a convicted murderer awaiting the death penalty for such crimes. This bottle is an offering to please Kwunubek.

Pots for Marassa Trois: Dedicated to the Marassa twins (though sometimes there are 3). These pots look like they are made of clay, and serve as an offering to the twins.

Paket Kongo and boat for Agwe – Paket Kongo sits inside a straw boat, with blue, red and green feathers/ribbons sticking out. The feathers and ribbons on top of the boat are meant to be a representation of and means of communicating with the gods.

Rhum Barbancourt – white rum bottled and produced in Haiti.

Sirop D’Orgeat – sweet almond-barley syrup, next to Paket Kongo and boat for Agwe, most likely an offering for him

Bottle for Minocan – Multicolored bands of sequins wrapped around bottle, two snakes of bronze sequins also wrapped around the outside. The variety of color is meant to represent many different Iwa without offending any of them.

Libation Bottle for the Gods Sin Majè/Ogou and Èzili Dantò – red, blue and white sequins covering the bottle with pictures Catholic Saints on the front. Roman Catholic saint Sin Maje is meant to represent Ogou, the red and blue colors are those of Ezili Danto.

Flag for Lasiren – flag depicting Lasiren, the queen of the ocean, as a mermaid. Being the goddess of the deep ocean, this flag is meant to represent her power and ability to lure people into the ocean, much like a siren

Statue of Twins – plaster statue of twin saints Cosmas and Damien, these twins are meant to represent the Iwa known as the Marasa. This statue is meant to be an embodiment of the Marasa.

When viewing the Haitian altar, the first items that somebody may see are the huge flags, or perhaps the color coordination of the altar. The flags are not typical items that are present on a Haitian altar; however, Professor Matory said to us that flags have become more of a symbolic item. The flags represent the Haitian revolution and the struggles the people of that country went through to get to where they are today. The flags were also gifts for Professor Matory. By looking at the flags you can tell how elaborately made they are and he felt that they were too pretty to not hang up so he added to them to the altar as well. Most altars used for the practice of Vodou are much less expensive, and are more practical. The next thing that is very noticeable is the colors or handkerchiefs that are hung on the front of the altar. The colors go from dark to light, and each color represents a Haitian god. They are used for spirit possession when a ceremony is taking place. The god that possesses the person has their symbolic colored handkerchiefs draped on the person being possessed. The altar is also covered with bottles of liquor and many different liquid items. These are all here as offerings to the gods. The certain liquors placed on the altar are what each god prefers. The bottle is placed in close proximity to the god that is represented by its Paket Kongo. These would be the odd looking structures that are on the altar: for example the black and red structure, which represents Kafu. The sculptures are set up in a certain way, with all the Petwo gods on the left and the Rada gods displayed on the right. The Petwo gods like more of the rough and hard drinks whereas the Rada like the smoother European liquors. Therefore, in the layout of the altar, the rough liquors are on the right and the European liquors are on the left, representing the transition from Petwo to Rada. One common thing associated with Haitian Vodou are “zombies”. Despite the instinctive response of zombies that comes to mind, Haitian zonbi are nothing like the glorified “zombies” known in Western media. The spirits of the zonbi are better known as the spirits of the dead that have been captured and brought back to work for someone. Western zombies are often the living dead, come back to kill the living and eat them; nothing like Haitian zonbi. Zonbi that reside on altars are often placed in bottles with elaborate beading and decoration. Some zonbi may be spirits that are related to whomever own the altar. Other times, as shown on this particular altar, the spirits residing in the bottles are spirits of the gods.

Other things that are displayed on this altar aren’t directly associated with the gods, but function as other “accessories” for the gods. One thing that is a little hard to display in a museum would be the food offerings. In Vodou, it’s customary to provide food to the gods on an altar, and the cooking and arranging of food is an important ritual. Unfortunately, our altar resides in a museum, making it difficult to provide food for the gods due to the rules and regulations that a museum faces. A fake cake sits in the center of our altar, with ceremonial candles placed on each side of the cake. This is meant to represent the food that would be offered. The two chairs on either side of the altar are for sitting, but sometimes a doll may be on the chair of an altar instead to symbolize someone sitting in the chair. The teacup in the front of the altar is used to hold libations for the gods or used to hold wicks with olive oil and honey to make prayer stronger. The maraca looking objects are used in the ceremony and to communicate or salute to the gods. Dr. Matory, the creator of the altar, informed us that the necklace is often worn by a Haitian priest during a ritual. Each bead or pattern represents each god in its colors. It is worn in a way that the spirits envelope people and include them all as a community, and to provide protection during a ritual. The statuette of twins represents the Marasa, the sacred twins of Vodou. The statuette is placed on the altar during rituals and food associated with children is offered to it. The three urns are pots for the Marasa. As long as the Vodou altar follows the basic blueprint of having Petwo and Rada spirits (and their associated bottles and liquids) on different sides, and the scheme of light to dark, the exact placement and specifics of an altar is left up to the creator. The altar is a creative structure, and no two altars will look the same.

From the perspective of the altar, we can learn more about religion than we realize. The study of religion is a field that can often be majorly biased without malicious intent. Too often, religions of the world are studied by Westerners in the way that they study Western religions such as Christianity, Judaism, or Islam. Religions such as these are often studied and categorized by their beliefs and their ideas of gods, holy spirits, and morality. Western religions often idolize those who live without materiality such as Mother Teresa, and focus on becoming a pure individual with no greed or lust. These beliefs of spirituality and morality can be a good way to observe some religions, but not all religions in the world are defined by such beliefs. Many religions have more facets than just spirituality; religions can also be seen from aspects of materiality, storytelling, rituals and traditions, and more. The Western way of viewing religions isn’t universal and in many cases, it just doesn’t work.

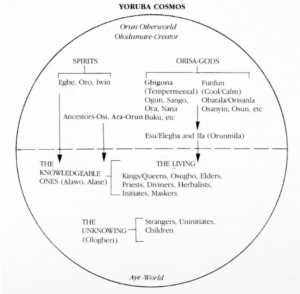

By observing altars and materiality, one can observe a whole new side of religion that may have been invisible before. While approaching religion from this angle may not provide much insight into religions such as Christianity that promote modesty and dissuade materialism, many other religions place objects in a role that is essential to their worship. For example, altars in religions of the African diaspora such as Yoruba, Vodou, Santeria, and Candomble often have symbolic bottles, calabashes, or other tokens of worship. Worshipping objects that contain the spirits of gods or that were purposefully placed upon an altar to please the gods is an important part of many non-Western religions, and is an act often overlooked when religions are studied from a purely Western perspective. By focusing our study on altars, we as outsiders gain a deeper understanding of religions such as Vodou than we would have from simply trying to understand Vodou from a perspective of spirituality and morality. However, studying the altars of a religion isn’t a perfect method of understanding the religion either, especially when trying to manage the difficulties that arise from an outsider trying to define a religion they aren’t involved in. There are many aspects to a religion, and just because someone is studying a concept such as materiality that is more active in a certain religion doesn’t mean that they suddenly have all of the answers. There’s a lot to consider in the study of religions, such as ritualistic actions, music and storytelling, and worship.

While an altar might be a good entry way to learn about Vodou, it isn’t an all-encompassing perspective. This also brings up the perspective of the outsider – someone studying a religion from the outside won’t be able to understand aspects of the religion without being influenced by personal bias or ignorance. For example, while an outsider may view an altar as objects on a table, a practitioner of the religion will be able to see true meaning behind the objects and how they’re arranged to channel spirits or please gods. Putting emphasis on defining a religion by its materiality is a way that can promote the blindness that comes with the view of the outsider, even if it’s a preferable alternative to only focusing on a Western study of religion. Altars also viewed by people studying religion are often viewed in situations out of context, such as in a museum. By taking the altars out of context, it can often take away a huge aspect of the altar’s meaning and purpose. The study of altars as a means of defining religion through materiality is not perfect, yet it does provide a more appropriate viewpoint of religions such as Vodou in which materiality is important. Overall, although materiality may not be an comprehensive view from which to study religion, it remains invaluable for its ability to encourage outsiders to begin to look at religions from non-Western perspectives and to broaden the way that Westerners view religions that they aren’t familiar with.

The syncretic qualities of Spiritism allow us to gain an understanding of where certain Spiritist values are derived from. Spiritism is oriented around communication with ancestors that often takes place in the form of spirit possession (Bettelheim 314-315, 2005). Interestingly, this core value of Spiritist belief in communication with ancestors is believed to have been a result of syncretization with Native American cultures (Romberg 70,1998). In connection to syncretization, altar construction is considered “fluid, mixing a variety of religious systems and iconographies and inventing new ones” (Bettelheim 314, 2005), hence the inclusion

The syncretic qualities of Spiritism allow us to gain an understanding of where certain Spiritist values are derived from. Spiritism is oriented around communication with ancestors that often takes place in the form of spirit possession (Bettelheim 314-315, 2005). Interestingly, this core value of Spiritist belief in communication with ancestors is believed to have been a result of syncretization with Native American cultures (Romberg 70,1998). In connection to syncretization, altar construction is considered “fluid, mixing a variety of religious systems and iconographies and inventing new ones” (Bettelheim 314, 2005), hence the inclusion  are perso

are perso