this is a link to the google doc

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1KqPcjf-NsBxyzSE64VhDEaa8Oh1SR5RMuSXYR9jdo9k/edit#

this is a link to the google doc

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1KqPcjf-NsBxyzSE64VhDEaa8Oh1SR5RMuSXYR9jdo9k/edit#

Walking through “Spirited Things” exhibition in the Flemming museum, one object in particular caught my eye. It was a small cylindrical object with rings of red beads and grey putty. As I approached it, I learned it was called the “Beaded Thunderstone for God Changó Macho”. Examining it closely, I noticed how its base was a stone, and that the beads and putty were made around it. Next I looked at how the putty had gems pushed into it, and that there was figure in the center that began on a ring of putty and eclipsed through a band of red beads. This body sat with its legs crossed wearing red and gold pants. It had a small gold garment cloaked around his top, with a green gem on the chest, and a red one on the stomach. Finally, above this figure’s head was a plastic eye, and just above that was small crystal, sticking out of the top of the stone. After observing it, I thought about what its purpose was. More specifically, How is this intricate rock connected to both specific and general aspects of an entire culture? In this essay, I will examine the meaning of the Thunderstone, and how this meaning ties into the African Diaspora.

First of all, the African Diaspora is the culture from the Yoruba people in Africa that has been scattered through the americas predominantly through the slave trade. Along with being forced across the ocean, the Africans were forced to adapt their religion because slave owners wouldn’t allow them to practice it. Each different region of slaves adapted differently, creating a variety beliefs that root from the original Yoruba religion. In the Cuba, Venezuala, and all around Central America, the slaves were forced to adapt, and Santería emerged as their religion. Santería is the fusion between Christianity and the religion of the Yoruba people. The god or orişa Changó is a major god in both the Santería and Yoruba religion. He is the god of lightning and thunder and is very powerful and fierce. In Santería, he was represented as Santa Barbara because she had the same colors as Changó and was thought to be in many ways like the god himself. The Roman Catholic influence on the Yoruba religion through the means of slaves altering the Christian religion to be able to worship their own, is what lead to the popularity of Santería.

Changó Macho is one of the gods in Cuban Santería, along with Oşún, Obatalá and Yemaya. His colors are red and white, and he represents drumming, thunder and masculinity. During his life as a man, Changó was a mediocre king, but after death he achieved many great feats and became an orişa. Along with sharing the same colors, Changó and Santa Barbara share a fierce, tough and determined attitude. These aspects and colors can also be found in the thunderstone, except the symbolism is in the rocks physical properties.(Santeria Church of the Orisha, n.d.)

The first aspect of the Thunderstone that I wanted to look into, was its purpose. I wanted to know what its function was in the life of those who used it. After researching this question, I found that “Changó’s sacred thunderstones are stored in a ‘batea’ (wooden vessel) on top of a ‘pílon’ (upturned mortar)” (Ayorinde 2004, 212). In learning this, I figured out that the Thunderstones were most likely used as holy objects on altars.

In the original Yoruba religion from Africa, altars were set up by individuals to connect with the orişa that the altar is dedicated to. There is no one way to set up an altar according to the religion, but rather each altar contains objects significant to both the orişa and the individual making the altar. The altar by itself does not have any spiritual connection to the gods until it is activated in ritual. The rituals contain song and dance which empowers it with spiritual energy of Ashé, which is believed to flow through all living things in the Yoruba religion. Once the altar has been activated, the practitioner is then spiritually connected to the god and can even communicate with the orişa. During the slave trade, Santería would still have altars, but they would be disguised for Christian saints, but overtime the need to worship in secrecy has been diminished.

Since the thunderstone belonged on an altar, it must have been significant to Changó. With my previous knowledge, I knew that Changó was the god of lightning and that he was huge in war, and manly power. I was curious about why the thunderstone was significant to Changó. Going deeper in research, I found that the thunderstones were significant because it resembled Changó. The thunderstone is symbolic of Changó because its “(a) tough to crack; (b) a rigid frame not easily disintegrated by reality; (c) highly adaptable; (d) and sanctity/morality/truth, or re-affirmed action of the social order”(Lawuyi 1988, 136). Each of these reasons connect the physical aspects of the rock to the characteristics of Changó. For example, the rock itself is tough to crack, but that does not mean Changó is made of steel. Changó’s personality and honor is what does not crack.

Along with the toughness of the rock, the artistic side also has a tremendous connection with Changó. The red beads and the white gems, crystals and cowrie beads are symbolic of his favorite colors. Another aspect of the art is the black and gold figure on the front. This is a representation of the very masculine side of Changó, Changó Macho. The museum describes Changó Macho as, “to have dressed like a women in order to gain access to normal female spaces… The sculptural representations of Changó that are distinctly male are called ‘Changó Macho’”(SABA). The duality in how Changó shows how gender is both important and equal. This is because Changó, one of the most important Cuban Santería orişa, is portrayed equally important as both man and women, not more important as one gender. These aspects of the thunderstone that relate to Changó give an insight to the beliefs of the practitioners and what values of their god is important to them.

The thunderstone is a sacred object used on altar for Changó, because it resembles and is significant of Changó. This is the specific purpose of the thunderstone to the god Changó, but I am also interested in the general purpose of thunderstone as it plays a part in ritual along with the religion. In order to dissect the general purpose of the thunderstone, I examined altars as a whole. As stated previously, the objects on altars are supposed to be significant to the god the altar is devoted to, and the individual. Since practitioner is worshipping the god, what is important to the god should be what is important to the individual. In realizing this, I see now that altars are how the practitioners interpret the gods, and that the objects on the altar represent the values that the practitioner worships in the god.

As I considered this idea, I thought about other places in the religion where notions similar to this one come up. As I looked into it, I saw that the syncretization of Changó shows what values of the god was important to the slaves. Instead of representing Changó as a strong male saint, they chose Santa Barbara. The tough and fierce persona of Santa Barbara along with correlation of personal taste(color preference) show how the saint and the god both represent similar values to those that had to adapt the religion. It is also important to note that the misconceptions of men being greater than women was pretty much non-existent among the Yoruba at the time of the slave trade, because men and women both had equally important roles in the religion(Castillo and Mederos 2007, 151-157). This shows that gender was an important value to the people of both Santería and Yoruba, each gender being just as important as the other.

Through analysing both the general and specific purpose of Changó’s a better understanding of how each part of the religion connects to each other can be drawn out. The altar holds all these items which represent the god to the individual. Collectively, the altar is the is the god in the sense that it has all that values and representations of the orişa, but without life. Then it is up to the individual to bring life into the altar with song and dance, and bring life into the god that they are worshipping.

In conclusion, the purpose of the thunderstone is that it is a sacred object for an altar. By analysing this purpose, so much more information about Changó and Santería can be drawn out. The reason the thunderstone is a sacred object to Changó is because physical properties of the thunderstone represent the spiritual values of Changó. These values are then interpreted by the individual and worshipped in the form of an altar, specific to the practitioner. The accumulation of the symbolic objects along with the activation of the altar bring life to the values, turning the altar into a spiritual form of the god.

Ayorinde, Christine. 2004. “Santería in Cuba: Tradition and Transformation.” In The Yoruba Diaspora in the Atlantic World edited by Toyin Falola and Matt D. Childs, pp. 209-225. Indiana University Press, 2004.

Castillo, Daisy R., and Mederos, Aníbal A. 2007. “Lo femenino y lo masculino en la Regla Congo o Palo Monte”. In Afro-Hispanic Review, Vol. 26, No. 1, African Religions in the New World, pp. 151-157. William Luis, 2007.

Lawuyi, Olatunde B. 1988. “Ogun: Diffusion across Boundaries and Identity Constructions.”African Studies Review Vol. 31, No. 2 (Sep., 1988):pp.127-139, http://www.jstor.org/stable/524422?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=((thunderstone)&searchText=AND&searchText=(shango))&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3D%2528%2528thunderstone%2529%2BAND%2B%2528shango%2529%2529&refreqid=search%3A8cc1dc2eadc54a0d174b8cc014501bfb&seq=10#page_scan_tab_contents.

Santeria Church of Orishas. N.d. “Chango.” Accessed November 4, 2017. http://santeriachurch.org/the-orishas/chango/

Eli Van Buren

Cast to the back and to the side edge of the altar it appeared largely unimpressive standing next to the other, more flashy and colorful objects upon the altar to Yemaya. I think that is why it initially caught my eye. It appeared to be some sort of shell-covered model house, dust covered and a dull gray color from age. I’ve found that for the most part, some of the most discrete things turn out to be the most interesting. Naturally, I had to get closer to this dusty old box and as I did I realized it was quite a bit larger than I had first thought, about fourteen inches in diameter. It was almost totally covered in cowrie shells with a curious bird figure perched at the object’s crown. This was an Ile Ori, or House of the Head, a personal shrine dedicated to one’s own spiritual essence, individuality, and chosen destiny.

Ile Ori are hollow containers, usually with a cylindrical base and a conical lid. The Ile Ori wears scales of cowrie shells (an ancient currency among Yoruba peoples) which are symbols of great importance. The shells represent a triple meaning, as traditional currency they symbolize the riches of one’s good character; the overlaying cowrie shells allude to the feathers of a white bird; and the color of the shells, white, is the color of purity of character: iwa (Thompson 11). Commonly Ile Ori will even have a sculpture of a bird at the container’s apex. This bird is the eiye ororo or “bird of the head”

It is the bird which, according to the Yoruba, God places in the head of man or woman at birth as the emblem of the mind. The image of the descent of the bird of mind fuses with the image of the coming down of God’s ashe[spiritual essence that which embodies all things] in feathered form.

Thompson, 11

Moving on from the eiye ororo to other aspects of the lid, this particular Ile Ori has panels of alternating canvas, leather, and mirrors. Paired with the Ile Ori being specific to only one person, the mirror panels on two of the lid’s sides compound themes of individuality. Other materials were included in making the Ile Ori. Possibly the person’s placenta in addition to certain symbolic materials, such as clay, stone, or water (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27). Some objects represent different gods or oriṣa, depending on which oriṣa the person worshiped those materials would go into making the Ile Ori. Symbols appear to be an ongoing theme in Ile Ori and even the shape of the lid itself is of great importance. The cone has long been a symbol of humans and their place in the universe (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27).

Despite commonplace first appearances, this object has a hidden symbolism that transcends time to still be relevant today. Thinking of the Ile Ori as a personal altar will help understand exactly what the Ile Ori is. There is a common western idea of altars being entirely a raised platform upon which holy objects are placed. In understanding the Ile Ori, the concept of altars will expand to something greater. The Yoruba use altars in many things, and their altars come in many shapes and sizes. The Ile Ori is one such example, as the altar to oneself, celebrating individuality.

How can I begin to describe Ile Ori, the House of the Head, without first explaining the meaning of the head within a Yoruba context? Yoruba peoples, and those following Yoruba traditions, believe that one has two heads: an outer spiritual head (Ori Ode), and an inner spiritual head (Ori Inu). One’s outer head is physical, it was created with the body at birth. One’s inner spiritual head is much more complex, it contains a person’s iwa: their good (or in some cases bad) character, as well as the destiny they chose in heaven before descending to Aye: the world of the living (Thompson 11). The ori inu is also the site of one’s aṣe/ashe or life force. It is for this reason the Yoruba believe that inner qualities have a direct impact on the outer ones. This concept has been compared to a smoky flame: no matter how beautiful the smoke, inner ugliness will burn through, and vice versa (Thompson 11). In worshiping the head, heavy values are placed on one’s character. As an altar the Ile Ori functions differently in how it has a highly individualistic focus (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27). Centering around one person, each Ile Ori is only the shrine to one Ori.

There is no direct english translation for the word Ori. Ori can mean ‘head’, but it also means ‘destiny’, the two are interchangeable. The Yoruba have a strong belief in the concept of predestination and there are many words it is known by (Thompson 11). Though no matter the word used to describe predestination, it always comes back to be associated with Ori (Abimbola 115). People will visit a babalawo (diviner/fortune teller) to understand their chosen path in life through consulting their Ori and determine what it wishes of them. This practice is so universal that even the gods themselves have Ori guiding day-to-day life and will consult them from time to time for the same purpose (Abimbola 115). While the Yoruba believe in predestiny they also believe that each and every person chose that destiny. If someone is unsuccessful in life, it is largely due to the fact that they chose a poor head in heaven. So the head is a peculiar symbol of both free choice and predeterminism. The Yoruba even have proverbs describing the concept of Ori in this context:

Eni t’o gbon,

Ori e l’o ni o gbon.

Eeyan ti o gbon,

Orii re l’o ni o go j’usu lo

He who is wise,

Is made wise by his Ori.

He who is not wise,

Is made more foolish than a piece of yam by his Ori.

(Abimbola 114)

This sheds some light on how much impact Ori has on an individual. One of the worst insults one can be called is oloriburuku, which translates to “owner of a bad head”. To be called this is so offensive I probably should not have included it in this essay. It basically means that the offended is going nowhere in life and they chose to live a life of absolutely no worth. With such significance placed on symbols of the head, it really is no wonder this culture constructs altars dedicated to them. The Ile Ori is a way of prayer to appease their personal spirits as well as connecting with one’s inner spiritual self and their destiny (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27).

Nothing on or in an Ile Ori is there for no reason. Think about a modern western conception of an altar, each object or color has its specific symbolism or meaning. The Ile Ori is an altar, a shrine to a god named Ori. Ori is the god of the self. In some ways, Ori is the most important deity in the Yoruba pantheon (Abimbola 114) for it is respected as a personal god, and owned by a single person. Each person’s Ori belongs to them and it is understood that they will be more interested in personal affairs than the other gods, who are owned by all people (Abimbola 114). In worshiping their Ori people will place objects within the Ile Ori in order to please their Ori. It is in this manner the Ile Ori is given life, it becomes an aṣe-infused object with a very active role in a person’s life.

Opposed to other Yoruba, Vodou, Santeria, or Christian altars where everything is clearly visible and open to all people, the Ile Ori is a private altar. It is very unique and personal to a single individual, and so it is an altar closed to the prying eyes of others. Objects are placed inside the altar instead of upon it. The object placed within is called iponri. Iponri is a vital figure containing elements of one’s ancestor spirits, potential restrictions in life, and the oriṣa. This iponri is “everything that plays a significant role in the life of the person.” (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27) This proposes a new definition of what an altar is. Objects and offerings are placed within, not only to appease their Ori, but to improve their own destiny. A Yoruba proverb speaks of the constant human struggle on earth, stating that most humans chose poor Ori, poor destinies, in heaven. Through life people struggle to achieve the impossible goal of improving their predetermined bad destiny (Abimbola 146).

As a personal shrine, the Ile Ori challenges what I previously thought of as classified as an altar. Altars need not be dedicated to gods, oriṣa or spirits. The Ile Ori has shown me worship is dynamic and unconfined to being directed towards higher beings. As an altar, this object channels aṣe/energy towards the self. It beautifully balances self-love with self-improvement within a spiritual symbol. The Ile Ori tells us to purge bad character yet still appreciate yourself, to be happy with you lot in life yet still work to improve it. Through studying this Ile Ori my concept of altars has expanded. As an altar so centralized around individuality, it is very different than other altars, which have the effect of bringing people together. The Ile Ori introduces a rarely seen, yet vastly important, spiritual form; that of self worship.

“Òwèrè là ńjà”: we are only struggling

Abimbola 146

Drewal, Pemberton & Abiodun, The Yoruba World. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New

York, (date needed), pp. 26-33

Abimbola, ‘Wande Ifa: An Exposition of Ifa Literary Corpus. Oxford University Press Nigeria,

Ibadan, 1976, pp. 113-147

Thompson, Robert F., Flash of the Spirit. Random House, Inc., New York, 1983, pp. 11

Seth Epling

The object was stuck in a falling state, suspended in mid air. A weapon among an altars, a scepter surrounded by crowns. I wanted to know why there was such a violent looking object in a place where everything else is full of color and life. The scepter does not stand out. It has little color and small designs that are worn away. The handle is a simple, wooden staff. The kind of wood that if you held it, it would give you splinters. There are three brass segments on staff. Above the one at the top, there is a catlike creature. It is a very interesting creature with a big cat body and long ears or horns. The shadow this creature cast upon the wall intrigued me and prompted me to chose this object. Right before the axe head, two horns protrude out of the wood. There is the blade that is made of metal with a tidal wave design throughout the edge. There are two metal pieces that hold down the blade, an S shaped piece and a spring piece. The last thing on the scepter is a flower with 6 petals right below the horns. On every other petal there are bumps that seem to make a simple pattern. Why is this deadly object in a place of surrounded by objects of worship? This question even relates to the scepter itself. The flower on the staff begs the same question. I wanted to learn everything about this scepter and the god it represented, Hevioso. Contrary to its looks, it is not a weapon, it a tool used for religious and political festivals. Why use a violent looking object to demonstrate religious and political power. The answer lies in the god Hevioso. As a hot god, Hevioso does things quickly and people who have him as a deity are usually in power. This leads me to argue that this scepter was used to show power over the king’

s followers. In the rest of the paper, I will first explain how ase (às̩e̩ or ashe) plays an important part in understanding this object. Then I will explain the cat creature on top of the staff and the significance it has towards the scepter. I will then give background on the implications of ase, Hevioso and how King Glele praises Hevioso and basic information on vodou and Yoruba tradition. Next, I will talk about a king who was represented by the same god, Hevioso, King Glele and will then show how the scepter would be used in a festival based on first hand basis of people who research the religion.

For any object in the religion of vodou to have any significance, it needs to have ase. Ase is a word that most closely means it has power and meaning. According to Professor Abiodun, a Black Studies professor at Amherst college, for any object to have ase, it needs be be activated and be in context. An object has to be active in order for the real meaning to be found. Activation means that there is a deity that is apart of the object. This deity gives the object power and context. I use context because art and parts of festivals can not be taken out. There are no art exhibits in the yoruba and haitian land because those people are living in parallel with their art. What we would put on display they use in their everyday life and it has way more meaning with them using it. This is one reason why looking at this scepter as it is hard to understand. It is being taken out of the ritual which it was crucial in.

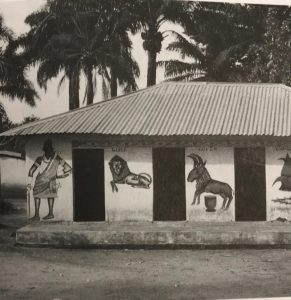

Ase would be present in the scepter as a whole but many of the small parts also would have contained ase. One of the smaller parts that would have had lots of ase was the creature. The cat creature on the scepter is a symbol for both the king and Hevioso. In the picture of the Nesuhwe shrine house in Abomey from the book Asen, Ancestors, and Vodun there are two animals. There is a lion with a name above that say “Glele” and on the right side, there is an animal for “Ghezo”. Ghezo is the predecessor to Glele and his father. King Glele will be discussed later in much more depth. This animal is thought to be a buffalo because one part of his symbol is a buffalo, according to the new world encyclopedia. These two animals have something in common. They both have incredible brute strength, are insanely fast, and are fear in the animal kingdom and by humans. This is important later when I discuss Hevioso.

Photo by E. Bay

In what is now the country of Benin, there was a kingdom named the Dahomey kingdom which ruled for around 300 years from 1600s-1900s. This kingdom was ruled by many kings who passed along their status to their children. The main religion was Vodou, a religion based of the following of spirits. Some of these spirits are ancestral, but every person has a deity that guides their journey. This is very similar to the religion of Yoruba, many of the gods between these two religions have the same duties but have different names. Yoruba is a major religion in West Africa, including Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. Yoruba was the precursor to many other religions, including vodou, that now span the world. This fits in the category of diaspora religions, or religions that were spread because the atlantic slave trade.

Every king had their own scepter to show power and royalty. Each scepter also was a symbol for the god that the king represented. One god that many kings represented was Hevioso, the god of thunder for Vodou, whom is similar to Shogun, the god of thunder for Yoruba religion. “Hevioso is associated with the lightning-like gunfire and cannon during battle… Hevioso played an important role in war.” (Blier, 51)..Hevioso is a god that likes to accomplish things quickly and effectively which is why many kings felt empowered by him. Hevioso is considered to be a hot god or petwo which is misconceived as an angry god. This is a misconception because Hevioso was helpful to the king and did what the king requested but his style of actions was perceived as angry. Often, Hevioso is represented as a lion or an animal that is both mentally and physically strong because of his pride and his intensity. Hevioso by The 69 Eyes. This is a song where Hevioso is praised. In the song, the beat is made to sound like thunder, there is a lot of bass which emulates the feeling of when thunder rumbles throughout the land. Looking back at the two animals that represented two kings, the lion and buffalo, it is easy to see how they relate to Hevioso. They are both fierce and strong. They both do things that the believe are right for themselves and who they take care of. The kings who felt empowered by the animals and Hevioso wanted and needed to have these traits in order to be a leader for Dahomey.

King Glele was the king of Dahomey for many years, had Hevioso guiding him. He was a military genius and spent many of years of reigning on the people he conquered. He earned the nickname of “Lion King” and “Lion of Lions” because of his ruling style. Below is a court song about his reign.

“King Glele,

the one who cannot be taken

Lion of lions

The Animal grew teeth

and all the forest trembled

The animal that eats

the other animal with bones

The lion is afraid of no animal” (Blier, 52)

This court song is saying that King Glele is one to be reckoned with. The people did not literally see him as an animal, but they believed the lion was apart of him. Fon people, the people who follow vodou in Benin, admired him as their superior. He was a fearsome ruler and stayed in power because of the fear he inflicted on people. He would not go around hurting his own people, but because of the vodou religion and the implication of him having Hevioso as his deity, he was able to keep the people below them in their place.

The scepter was an violent looking object and King Glele had a similar procession. He commissioned the making knives of abnormal sizes. According to Adjaho in Bliers writing, the making of the knives is to show great amount of force and that there would always vengeance. These knives made for King Glele and the scepter that I am examining were used in the same festivals and courts. These knives were used to punish criminals, promote and pay court officials, celebrate military victory, display wealth of the royal family, and as a tribute to the royal dead. according to Blier. These weapons were used as a way to show both physical strength and political clout. Also, kings used these armaments to show how much power and money they had as well as to demonstrate the greatness of their armies.

Looking at this object again, it might look quite simple. It is just an axe with simple designs, but it is way more then it seems. Although we do not know what king this specific scepter represented, it is easy to draw connections from King Glele and the vodou tradition to show how and what this scepter was. The axe-like head was a sign of power and ferocity, this king was a strong and frightening. It was used in many festivals, just like the knives, to honor royalty, military victories, and deaths of important figures. It was also used in courts to punish criminals and force the payment of court officials. It is hard to see the significance of this object because it has no ase while in the museum, but it gives enough background and explains enough to understand the impact this scepter had on people. So there is a reason that such a dull, deadly looking weapon is in this museum. It is a work of art. Although it is not as colorful as the other objects it has just enough significance if not more.

Bibliography

Bay, Edna G. Asen, Ancestors, and Vodun. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Blier, Suzanne P. “King Glele of Danhomè, Part One: Divination Portraits of a Lion King and

Man of Iron.” African Art 23, no. 4 (October 1990): 42-53. JSTOR (3336943).

Brown, Karen M. Vodou in Haitian Life and Culture. Basingstoke, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan

Accessed October 30, 2017.

“Kingdom of Dahomey.” New World Encyclopedia , Edited by Frank Kaufmann, 11 May 2015,

The Spirited Things exhibit in the Fleming Museum is a lively display of altars and artworks from various Caribbean religions. The exhibit is erupting with color, wonder, magic, history, and life. Each piece was curiously unfamiliar to me, some more than others. It was difficult to identify the piece I was most interested in–there were dangling tassels, glittery fabrics, and bright colors at every turn. I was drawn to the Gelede Mask because of it’s quiet, powerful appearance. It contrasted with other objects in the exhibit in that it was not decorated in a particularly eye-catching way–it was composed of primarily earth tones, and its display was simple and uncomplicated. It was standing alone in a minimalistic glass case, located in a section of the museum dedicated to items related to gender–a topic I take a special interest in. The mask displays a woman’s face, decorated with a snake wrapped around her head, and a warthog and hunter on the back side. This first section of this essay will discuss and raise questions about the gender dynamics within the history of the Gelede mask–while the second section will explore the implications of African art, such as the mask, on display in Western museums, and the limited possibility of translation of meaning between these two cultures.

The gender dynamics at play in the Gelede ritual illustrate the limited, yet paramount role of women in Yoruba rituals. The Gelede mask was created in July of 1983 for use within the Gelede festival in Nigeria–a spectacular ritual that pays homage to the spiritual powers of women. The powers possessed by such women are believed to influence the flow of good and bad events in practitioners’ lives, and can be used for the benefit/destruction of society. These powers are comparable to those of gods, spirits, and ancient ancestors of Yoruba peoples. Women (usually elders) who use their spiritual powers for destructive purposes are deemed witches in Yoruba culture. The Gelede ritual’s aim is to influence the witches to use their powers for good versus evil. Interestingly, men perform this ritual wearing masks that depict the faces of beautiful women, and extravagant dresses and skirts to complete the imitation and performance. In a ritual dedicated to women and their power over society, only men are allowed to participate. Women observe from the sidelines of the ritual, watching and judging the men’s imitation of their own gender. In Men Portraying Women: Representations in African Masks, an article by Elisabeth Cameron, professor of history, art, and visual culture at the University of California Santa Cruz, the woman’s take on the Gelede ritual is perfectly captured:

The mask itself, then, is not the only element in these portrayals: in performance the male dancer imitates the movements of a woman. The young girls and women watch these embodiments of the feminine ideal, understanding that the conduct of the masquerade is what men desire of them. As Manuel Jordan suggests, however, “Women are willing to accept the female model presented to them by men if they agree that it represents them appropriately (Cameron 1998, 72).

Cameron provides helpful insights into the woman’s perspective of the Gelede festival. In a ritual dedicated to the worship of women, not being able to perform it themselves must raise questions as to what the woman’s role in Yoruba ritual really is. Instead of participating, women observe the embodiments of the feminine ideal, as Cameron states, and agree to accept this uneven distribution of power within the ritual if the men’s representation of them seems accurate and fair. Is it not strangely hypocritical to celebrate the power and importance of women within society, without including them in the process? The design of the mask brings about similar questions–the mask depicts a hunter on the back of the woman’s head, as if he was controlling her. The hunter’s placement brings about some questions related to gender relations both in Yoruba culture and in the Gelede festival. Does the hunter also convey the idea that men are ultimately in control of these traditions? If the powers of women are as feared and worshiped as the Gelede ritual ritual suggests, it seems risky to exclude women from such important practices that could affect the wellbeing of Yoruba society as a whole. As seen in the photos attached, this mask is a beautiful and culturally charged piece of artwork–but the Gelede mask also functions as a spiritual altar, due to its use in ritual practice.

Spiritual altars in Yoruba cultures provide ways to call spirits, ancestors, gods, or other symbolic beings (such as witches) to a specific place. Altars are often adorned with beautiful decorations and offerings to various orisha (gods). Most often, altars are long tables or displays full of spiritual objects and vessels, some containing the essence of different orisha. The Gelede mask on display in the Fleming museum does not appear to be an altar in the traditional sense of the word–however, the Gelede mask functions as an active spiritual altar among Yoruba people who practice Gelede tradition. It’s purpose is, indeed, to call upon spirits of witches and attempt to guide or influence what they use their powers for. This type of altar is different than a traditional table altar, in that it is actively used in rituals rather than observed and simply used as a place to leave offerings and extend worship to the different orisha. The Gelede mask can be described as art with a purpose.

All African art is created with the idea that it must have a source of life to hold meaning. In Professor Rowland Abiodun’s book, Yoruba Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art, he discusses the idea that artworks in Africa need to be ”activated” by some form of energy or life in order for the art to reach its full potential, along with the doubt and skepticism that Westerns have shown towards this idea. Such is the case with the Gelede mask: until it is activated by using it in symbolic rituals, the mask does not hold nearly as much meaning as it would after it’s been infused with life and energy from the Gelede festival. This source of life is called așe, and is used throughout Yoruba culture to describe the life force that is within people, artwork, animals, etc. This idea of aşe does not lend itself easily to straightforward description, translation, and analysis using Western terminologies present in the humanities (Abiodun 2014, 56). Aşe is not something that we, in the West, use to classify and qualify objects and people–however, in Yoruba culture, aşe describes a desirable force that, if present in a person or object, gives divine meaning and essence to said person/object. As the Gelede mask is used and therefore activated in the Gelede festival, its aşe increases as practitioners “breathe” life into the mask by using it in such a way that infuses it with energy from the spirits and witches it calls upon.

It is this concept of așe that creates a cloudy barrier between African art and the Western understanding of it. Abiodun states in his book that “African art was not even considered art with a capital “A” until relatively recent times, mainly because art was defined entirely by modernist Western scholars for whom art was ‘for art’s sake’” (Abiodun 2014, 2). In the West, the idea of așe simply does not exist. As Abiodun stated, art is created “for art’s sake,” with no such energy requirement as așe. This divide between the fundamental ideas of art causes me to wonder if the paramount gender conceptions present in Yoruba cultures that are represented by this mask can be translated in a way that will make sense to Westerners not familiar with the idea of așe. In Yoruba scholar Babatunde Lawal’s book, The Gẹ̀lẹ̀dé Spectacle : Art, Gender, and Social Harmony in an African Culture, the necessity of așe in African art is discussed: “. . . the human image, a masterpiece by Obatala, embodies a special power (așe), inspiring and sustaining the creativity manifest in the visual, performing, and applied arts . . .” (Lawal 1996, 24). Lawal’s comments can be analyzed to infer that it is necessary to maintain the așe in the Gelede mask in order to preserve and translate the conceptions of women’s roles in ritual practice within the Gelede tradition.

The așe of the Gelede mask is vital to the understanding of the tradition itself, along with the complex gender dynamics involved. However, one must question whether așe is now present in the mask at all, as it is currently on display in a glass case in the Fleming museum instead of being used in ritual practice. I believe that the Gelede mask is one of the most interesting items in the Spirited Things exhibit–it carries such complex connotations and ideas related to gender and the dynamics involved in the Gelede festival. It delves into the way women are perceived by both themselves and men, as depicted in the Gelede festival. but unfortunately, I believe that a lot of that is lost without the aşe normally present in the mask. The Gelede mask is a physical representation of the idea that African art must be alive in some way in order to reveal its purpose. This mask, and exhibit as a whole, demonstrates that African art is not created to simply sit in a case and be observed–although in the West, this is the first step to introducing such concepts as aşe to the art world. I believe the lack of understanding of aşe is why Western scholars took/are taking such a long time to validate African art. The idea that art isn’t meant to be still or on display is unfamiliar to these scholars, and unfamiliarity, in many cases, precedes dissent.

Bibliography

Abiodun. Yoruba Art and Language: Seeking the African in African Art. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Cameron, Elisabeth L. “Men Portraying Women: Representations in African Masks.” African Arts 31, no. 2 (1998): 72-94. doi:10.2307/3337523.

Lawal, Babatunde. The Gẹ̀lẹ̀dé Spectacle : Art, Gender, and Social Harmony in an African Culture / Babatunde Lawal. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

Ifa Divination isn’t an altar, it’s not part of an altar. It doesn’t belong on an altar. So instead when it’s in a museum where altars are present it gets represented on the wall and in a case. The museum exhibition, Spirited Things, houses these objects, some are displayed on an altar while others are in cases or hanging on the wall in a room. The objects representing Ifa Divination, hang on the left wall in the room with the Haitian vodou altar, and in the corner where gender specific objects are found. What makes me curious, is that divination is a Yoruba religion practice, so I get pulled in further. Then I notice it’s tucked behind a long display case. This brown wooden tray sits back behind the case. It wouldn’t be the first object you notice walking into the room, being concealed behind this big glass case. Then as I walk closer, the detail of the 4-inch board starts to become more vivid. There are faces and there’s animals, looks like armadillos and horses, and designs that are unknown but have a snake structure to them. The details on the face are flat and smooth. The grooves along the face are deep. But what’s different is that each design is pointed towards the middle. Like something should be demonstrated there, like a stage for a show, but the center is blank. Nothing but smooth, hard, brown wood. The whole board is about a foot and a half by a foot and a half and about 1-2 centimeters thick. There are two big faces, the biggest face rests at the top of the board. It has a flat nose and big protruding eyes. When looking at the board it’s the first carving that really pops out. I notice there is some symmetry on the board. The faces are across from each other, then there are the snake like designs on the left and right side of the board and then there are people and animals that looked scattered at first but then when you take a closer look you notice that they have some sort of pattern. There are two people, one of each sex, embracing on either side of the big face and they each have some sort of animal around them. Then there are other people around the board that look like the animals or the objects next to them have some sort of purpose to be placed next to them. Then as I read the description there are more parts that are described with this tray. There were two more items listed; pair of divination chains and the divination tapper. It then goes on to describe this person, a babalawo or what they also called it the “father of mysteries” so of course this “father of mysteries” is just, that a mystery to me. So naturally with my curiosity getting the better of me I wanted to know more about what these mysteries were and about the secrets of the babalawo. As I continue to read the description there is mention of Ifa, the first of the diviners. This again makes me wonder what the story is behind these diviners, what do they do? The description mentions that they have to memorize 256 odus. Which were poems, tales and prescriptions from the god Ifa himself. This was something that baffled me. Who could possibly remember that many poems, let alone some of them being stories. To me that was just insane. Naturally my curiosity grows. Then I take a look at these object, the chains and the tapper that is being described in the article. The chains are in a glass display case to the left of the tray. One of the chains didn’t really look like a chain. The other one however, was a made out of actual chain links. This one made sense to me, small, grey chain links that made up the whole chain. At one end of the chain links there is one washer, one small white shell and one small brown shell. The other end has one bell, a small white shell and one small brown shell. I noticed these bigger black shells that were present in each of the two chains. There was 8 in both of them. Then between the fourth and fifth shell there was a bigger gap that split the chain into two halves with four shells on each half. This again made me curious. How could these chains fit with this board? Do they hang them? Do they form some sort of pattern that corresponds to the board? Each shell on the first chain is separated by a yellow blue pattern of beads. At one end, there is a washer and one small white shell. On the other end, there is one small bell present. The questions continued to fill my head. Now I look at the tapper, also found in the same display case as the chains. Now my head really has some questions. This tapper is different, nothing like I’ve ever seen before. First, thing I notice is the huge head that this man has. It’s a giant head. Looks like it holds so much information. The man sits upon this upside-down cone. I go back to his head, he’s bald, he has this one protruding thing about his left ear. Almost looks like a tuft of hair. His head making him look very top heavy, if it were to be picked up. His neck is also incredibly long and skinny and he has a necklace around it. He holds something in each hand, looks like something flat and square in one hand and in the other he holds something to write with. All of this is made out of carved, solid, polished wood. If its name has anything to do with what it does, then I couldn’t imagine how. I don’t foresee this object being tapped on something. It’s too detailed too oddly shaped to be tapped on something. Just from looking at these objects I don’t know what to think. There are so different from anything I’ve ever seen and different from each other. I wanted to know more about how objects that look so different could possibly fit together and how they are used. In this essay, I will first give some background information on Ifa Divination then I will explain how these objects are used in the processes of and then I will go on to compare the objects with the concept of altars in the Yoruba religion based on the uses of these objects.

I had some background information of Ifa. He was the first of the diviners meaning he is the oldest babalawo. A babalawo is a messenger of sorts. He performs the divination for the client and then he recites what happens in the terms of verses or stories that he must memorize. Each story, or odu, has a meaning, and that meaning will correspond to what is going on in the client’s life. Then sacrifices can be made to try and get the good fortune back. When the babalawo is initiated into this priesthood, after about 12 years of training, he must memorize the 256 odus that can be recited during divination. Now you may wonder how an odu may be displayed during divination. There is a chain that is tossed on the divination board, where this marking and reading happens. The chain consists of 8 shells with a smooth side and a rough side. The chain is tossed 16 times and the babalawo marks down on the tray what the results of the shells were when they were tossed, whether or not they landed on the rough side or the smooth side. This pattern will then describe what odu Ifa is trying to relay to the client. The babalawo must recite what is being said by Ifa and express that to the client without knowing any information about why the client might be there to begin with. The client must decipher what the odu means to them and do as they see fit. This is strictly the job of a babalawo, he performs Ifa Divination is whole life until his time is up. As I continued my research another god, different from Ifa, kept popping up, Orunmila. The book Ifa Divination; Knowledge, Power and Performance, made Orunmila clearer; “Orunmila refers to exclusively to the deity himself, the name Ifa refers to both the deity and his divination system.” (Abimbola 1989 pg 51). Deity is another term for god, and from this information, Orunmila and Ifa are the same god, Ifa just refers to this process of divination itself. Therefore, when Ifa and Orunmila are mentioned during the divination process, the communication of the odu could come from either of the gods.

I look at the first of the three objects to get a better understanding of how the structure relates to the function of each, an image can be found at the end of this paragraph. On the top of the tray there was the biggest carved face. This face will represent Eshu, he is the messenger god. Because he is the messenger god, he is the god the babalawo will communicate with who will in turn communicate with Ifa or Orunmila. Some representation of Eshu must be present on every divination tray. This is because Eshu can be known as a trickster and having him on the client’s side, so they can get their information from the gods, is essential (Dialogue and Alliance pg 28). During Divination, Eshu is faced towards the babalawo, which forms a diameter that gives Eshu no shame in being present on both halves of the diameter, because he is known to be the only god who directly communicates with humans, therefore, they don’t want Eshu to be looked down upon (Dialogue and Alliance pg 28). There must also be a sacrifice given to Eshu before the divination can start as well. The other designs on the board are never to be constant out of respect for Eshu. Meaning that the other carvings differ from board to board making each one unique (Dialogue and Alliance pg 26). However, this brought up another question; why would these objects be present in the gender corner or the museum? The other carvings that are part of the board, usually represent other Yoruba life tasks. This would explain the animals, it could be the sacrifices or their food source, the loving embrace is reproduction, and so on. The most important carving is Eshu, which is clear that it is important in this Tray. The tray is used for communication between the gods during divination. However, the tray is only one of three very intricate objects.

(picture from the Spirited Things website)

(picture from the Spirited Things website)

The chains are the next object that came to my attention to analyze and understand, an image can be found at the end of this paragraph. The 8 shells on each chain was constant in both, so I did some research on this as well. These chains are used to be tossed on the board and some sort of pattern will come from this. The shells have a smooth side and a rough side. The babalawo uses the chains to cast patterns that will either show the shells facing the smooth side or the rough side, then the number of shells on either side is recorded. There is a total of 16 sections of odu that the babalawo has to work with. Each pattern will represent a different section that the babalawo has to interpret. There are a total of 16 shells or nuts because it is said that when Ifa left earth his children climbed a tree to get him to come back and in return he gave them each 16 nuts (Thompson 1983, pg 34). Another thing that seems to come up with this tree is white powder. This white powder also comes from this same tree and is used during divination to be sprinkled over the tray so the babalawo has something to record the patterns he sees that form the shells (Thompson 1983, pg 35). There are 8 on each chain and 4 on each half because when the babalawo is recording the patterns this way the possible combinations will equal 16. (witches almanac 2017). This is just a faster way to obtain these patterns instead of using just 16 shells off the chain. Most babalawos prefer to use the chains because it is a faster method. The function of the chains is more clear and easier to memorize with the structure because of the shells present on each chain. They are the information that is being communicated between the gods to the babalawo.

(picture form the Spirited Things website)

(picture form the Spirited Things website)

Every Babalawo uses a tapper. An image of the tapper being described can be found at the end of this paragraph. The tapper has a very easy job. It simply summons the gods, Ifa, Orunmila and Eshu. To bring to them their attention that there is a divination going on and they need them to participate (collections 2017). A tapper can have many different looks. It all depends on the artist who made it. Because I don’t have the artist at my disposal, I like to draw some conclusions as to why the tapper may look like this based on my knowledge. I think the size of the head represents that number of odus the babalawo has to memorize. There is so much information that he has to memorize that it makes his head swell with all his knowledge. I believe the flat square object in his hand is a divination board and the other is a tapper as well, but a much smaller version. I think the man himself, represents the babalawo. I did find out why the man sits on a cone like structure. It is actually supposed to represent a tusk, and elephant tusk. In the Yoruba religion, the cone is an ideogram for ashe. Ashe is divine power. Which represents all the power that is present and is needed for a divination ceremony. Therefore, the tapper is thus represented in this way (collections 2017). Now that the reason for the structure and how it relates to the function of these objects is known, there is also a reason why they are represented in a museum exhibition that has four different religious altars.

(picture taken by Alyssa Falco)

(picture taken by Alyssa Falco)

An altar is something that is worshiped by the people and made for the gods. The altar has many different objects that are worshiped and are placed in certain areas of the altar based on the liking of the gods. Each object represented on the altars have some connection to the gods. They are activated with the form of ashe, they all have ashe in them. Ashe is divine power. “Ase diminishes with inaction and strengthens with activity.” (Drewl, Pemberton, Abiodun 1990, pg 25). The objects must be worshiped on this altar in order for the gods to interact with the objects and for them to be worshipped and have meaning. “The altar is considered a threshold into another world.” (Thompson 1995, pg 50). The altar is the connection between the gods world and the human world. The divination tray is like an altar itself. As I mentioned when describing the board, it looked like a show was taking place. This is the altar; the divination tray is the altar that connects the world of the gods to the world of the humans. The objects themselves have to be activated as well. This is when the concept of ashe comes in, the objects have ashe in them in order for them to communicate with the gods. The objects have ashe in them that allow somebody who participates in the Yoruba religion to accomplish what they want. While performing divination the ashe in the objects and the tray as the altar, which is the connection between the worlds, allows for the client to get insight into their future. Therefore, the tray is like an altar and it belongs in this exhibition for that reason.

The museum exhibition has four different altars that represent each religion. Then there are objects that also fit into each religion based on what they may represent. The divination items can be found in the gender section of the museum. At first this may be very puzzling. However, when you take a closer look at the objects, you can see gender is displayed in the carving found on the tray. The tray has carvings of both male and female showing their dependency on one another in everyday life, but also their independence is displayed. The embracing is needed of both sexes to then move on and move forward in life. But then some of the carvings there is only one-person present on the tray border. The women can do everyday tasks on their own as well as the men. Symbolizing that each gender can be independent as well as they depend on each other. The tapper itself is also a carving of a man. Then for obvious reasons this would fit into the gender category. The structure of each object has a specific function in order to allow the process of divination to be performed. Without the 16 shells then the odus wouldn’t be able to be recited, without the tapper the gods won’t be summoned and no odu will be present and without the tray there would be no communication between the two worlds. The idea of divination itself is a ceremony that is for the people but it ties the gods into it as well. By asking them for their help or be asking them for a favor. The presence of an altar is again the same concept. It is made by the people and worshiped by the people because they want a sense of faith that they will have a good life as well. They feed their altars which then feed the gods to ensure a good life, Ifa Divination has the same idea. The people of these religions want to have a good life, they put their faith into their gods just as any other religion would. The objects that are used in Ifa Divination put on an excellent performance and allow the people of the Yoruba religion to have faith that they will have a happy life, something that every person wants, good fortune and a happy life.

Bibliography

Abimbola, Wande. “Aspects of Yoruba Images of the divine: Ifa divination artifacts.” Dialogue and Alliance 3, no. 2 (1989): 24-29.

Clarke, J. D. “Ifa Divination.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 69, no. 2 (1939): 235-56. doi:10.2307/2844391Olupona, Jacob K., and

Drewal, Henry J, John Pemberton III, and Rowland Abiodun. “The Yoruba World .” In Yoruba: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought , 13–43. New York : Harry N. Abrams Inc. 1990. https://bb.uvm.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-2315560-dt-content-rid-10754571_1/xid-10754571_1.

Rowland O. Abiodun. Ifa Divination: knowledge, power and performance. N.p.: Indiana University Press, 2016.

Thompson, Robert F. “Face of the Gods: The Artists and Their Altars.” African Arts 28 (1)1995: 50–61. https://bb.uvm.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-2315560-dt-content-rid-10661100_1/xid-10661100_1.

Thompson, Robert F. Flash of the Spirt . Toronto, Canada: Random House Inc1983.

Website Sources

https://collections.dma.org/artwork/5327077 – will be known as collections 2017 in the paper.

http://thewitchesalmanac.com/yoruba/ – will be known as witches almanac 2017 in the paper.

Alyssa Falco

One of the most striking pieces displayed at the Spirited Things: Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic exhibit is the statue of Esu found at the front of the exhibition. A picture of the object is found at the bottom of this essay. The sculpture is carved from wood, measures twenty-two inches tall, and rests on a circular base with a diameter of about ten inches. Esu, known to many as the messenger orisha, is depicted on horseback, surrounded by ritual assistants. The figures surrounding Esu are far less intricate than the orisha himself, who is flush with detail and variety.

The purpose of this essay is to examine the details of this representation of Esu, provide analysis of the individual components of the statue, compare this Esu to other representations of the orisha, and to examine how Esu corresponds with the African Diaspora. The significance of Esu’s position, possessions, and ritual assistants will be examined. Another focus of this essay will be the physical depiction of Esu and its deeper meanings.

Esu is one of the most important of the Yoruba orishas. He is not, as previously thought, only associated with decisions and not a part of daily human life. On the contrary, “Almost every traditional household, clan or village, every devotee (irrespective of the cult to which he or she belongs) has the symbol and worship of Esu,” (Awolalu 29).

It is through Esu that people can contact and request assistance from the other orishas. Esu carries messages between the orishas and humans. However, Esu is often referred to as a malevolent trickster. Esu sometimes carries messages to their destination, but sometimes willfully forgets them or takes them to the wrong destination. When this occurs, havoc is wreaked in the mortal world. Esu is not a fool or an easily duped trickster, but a powerful orisha who commands respect and has harsh consequences for those who fail to show it (Ogundipe 193). Esu must be appeased or he is more likely to be unreliable in his messenger duties.

At this point, it is important to stress that Esu is not an evil, malevolent, or harmful orisha in Yoruba religion. Esu has often been misinterpreted as the devil by outsiders, or being a purely evil being. “He tempts people, but that does not mean that he is against the human race or will do only harm,” (Awolalu 28). According to Awolalu, it is easier to imagine Esu as a powerful deity that can help or harm. When treated with respect and reverence, Esu often assists mortals in their tasks, but, if offended, Esu can cause volumes of trouble in the mortal world.

However, in Brazilian Candomble, Esu has a slightly darker role. While portrayal of Esu as the devil by missionaries was strongly rejected in Yorubaland, the narrative was more in line in Brazil, keeping in tradition with syncretizing orisha with Catholic figures (Ogundipe 213). While not wholeheartedly evil, followers of Candomble accepted that Esu runs both malevolent and benevolent errands, and therefore has a dark side. Another intriguing Brazilian twist on Yoruba belief is that Esu is sometimes referred to as a slave, as he runs errands for mortals for little compensation (Ogundipe 214). While powerful, the reverence and respect for Esu does not appear to be as high in Candomble as compared to Yoruba.

Esu is also the lord of the crossroads, beginnings, and endings. When a person faces a crossroads or difficult decision, Esu is present and guides travelers. However, he may lead them down the wrong path. The duality found in Esu’s nature (he can either help or harm) is reflected in physical depictions of Esu. Esu is often depicted with a protrusion from the rear of his head, ranging from a small protrusion to more phallic depictions (Ogundipe 157). In this sculpture, the artist chose to create a serpent emerging from the rear of Esu’s skull. The serpent has its own face, and is devouring a helpless animal. This brutal depiction contrasts to a benevolent humanoid Esu portrayed on the other side. The contrast between the two sides of Esu’s head signifies that Esu can be helpful and resourceful, or can be cruel and damning. The power and might Esu has is exaggerated within this depiction.

The details of this Esu shed significant insight into what the creator believed about the orisha. Esu is mounted on a horse, and, although now missing, probably carried a flywhisk in his right hand. Both the horse and the flywhisk signify royalty and military prowess. That Esu is depicted in this manner is indicative that he was highly revered among followers of Yoruba. The attendants following Esu are depictions of devout followers, who in real life would be special priests and priestesses dedicated to Esu. These attendants carry various medicinal herbs and other ritual items. Esu’s mounted position and close-at-hand devotees symbolize his power, might, and royalty. In many depictions, Esu is portrayed with long hair, uncommon among Yoruba people except for the powerful and royalty (Ogundipe 171). In most portrayals of Esu, it is clear that he is highly respected and revered.

One of the most interesting aspects of this depiction of Esu is the humanoid face. This wooden Esu has facial scars why typify a specific people foreign to Yorubaland. Esu is also depicted with a beard typical of the Hausa People. The Hausa are a Muslim ethnic group native to northern Africa. However, to the Yoruba, the Hausa are a foreign population. Why would a Yoruba depiction of Esu cast him as a foreigner instead of a native? The conventional dialogue would have Esu depicted as a native and the Yoruba a descendant.

In my research I discovered that it is common for not just Esu but all orisha to be depicted a hailing from a foreign land. The Yoruba had great respect for their foreign neighbors. Depicting their gods with characteristics typical of their neighbors is a clear-cut example for the love and respect the Yoruba showed to foreigners. This depiction of Esu is therefore helpful in establishing that the Yoruba were kind to neighbors. Upon further examination, this claim is reinforced by evidence showing Yoruba respect for trans-local persons (Awolalu 186).

Unlike many other religions, Yoruba and most diasporic religions are very welcoming of foreign persons and concepts. Diasporic religions often incorporate symbols, signs, and powers from other religions such as Christianity into their practice. In some cases, this was just an easy way to refresh old concepts. In others, followers were able to worship their religion inconspicuously where it was not tolerated. Examples of rephrasing Yoruba doctrine into Christian terms include Santeria using Our Lady of Charity and Cobre as a representation of the orisha Oshun. This flexibility and hybridity were essential to the life and proliferation of many diasporic religions as native Africans expanded across the globe.

This statue of Esu would be used to adorn an indoor shrine. It would be at sacred processions for a specific orisha. It would carry messages from worshippers to the orisha which they hope to communicate with, and would send messages from the spirit world to the mortal one. This statue would appeal for an orisha’s benevolent intervention in the mortal world. Its important duties make this sculpture an essential part of an altar.

The two-foot wooden sculpture of Esu found in the Spirited Things exhibit is rife with intricate detail and symbolic meaning. Every part of Esu’s depiction has deeper meaning than face value. Esu’s prominent position, his follower’s worships, his facial depiction, and his serpent protrusion all have significant meaning and help to establish what the Yoruba people thought and believed in relating to Esu.

Bibliography:

Falola, Toyin. Èṣù : Yoruba God, Power, and the Imaginative Frontiers / Edited by Toyin Falola. Carolina Academic Press African World Series. 2013. pp.18-20

Ogundipe, Ayodele. Esu Elegbara, the Yoruba God of Chance and Uncertainty : A Study in Yoruba Mythology / by Ayodele Ogundipe. 1978, 1978. pp.151-220.

Awolalu, Omosade. Yoruba Beliefs and Sacrificial Rites. 1979, 1979. pp. 28-186

When I walked into the museum after being told about our project I already knew that I wanted to pick something on the Haitian Vodou altar. There’s something about Vodou that has always intrigued me. Maybe it was its misrepresentation in media that made me want to learn more about it, just like with my interests in Paganism and Wicca. That morning I walked into the exhibit and over to the Vodou altar I noticed objects and details that I hadn’t noticed when we had previously visited. I was drawn to multiple objects that had feathers on them, objects that my prior knowledge of African diasporic religions couldn’t help me understand. There was one specific object with blue and red feathers and an orb and stem kind of shape that caught my attention. Looking through the booklet next to the altar I found the object and read about it. It was a pakèt kongo for the goddess Èzili Dantò, protector of single mothers and abused women. At that point I didn’t need to look at any other objects, I knew I wanted to research Èzili Dantò and the pakèt kongo.

A pakèt kongo is a kind of container. The one I chose is primarily red and blue and is completely made of fabric, except for the feathers. It sits elevated on the altar, the blue and red striped base is full and held with a blue ribbon tied in a bow. Ribbons come out from the middle of the base, pale yellow and sticking up like bubbles on top of a drink. As my eyes move farther from the center, gold ribbons with a green pattern of flowers and squares and red ribbons embroidered with blue flowers and stems and gold trimming curl outwards giving the rounded base the appearance of a blooming flower. Protruding upward from the pale yellow ribbons is a stem wrapped tightly in red fabric. Two feathers extend from the stem, wispy and bent. The large red one grabs my attention first, but the smaller blue one demands to be seen too. An intricate kind of calm intensity surrounds the object, which was at first confusing but as I learned more about Èzili Dantò and about how pakèt kongo’s work, I began to understand its meaning, how it’s used in Vodou, and how it represents Èzili Dantò.

Many African diasporic religions have the belief that when someone is sick or injured the problem is not just physical; it’s also spiritual. It is usually thought that the problem occurred because whoever is sick or injured has fallen out of sync with the universe. The problem is then addressed ritually and holistically. In Haitian Vodou practitioners see doctors when needed, like for broken bones or serious illnesses, but the issue is still taken care of through ritual healing ceremonies in order to restore balance to the spiritual side of things. Most, if not all, of these rituals involve pakèt kongos.

The ancestor of the pakèt kongo is the nkisi, a healing bundle that comes from Kongo in Central Africa. There are minkisi (plural of nkisi) that have a kind of stem-on-globe shape, and then there are minkisi figurines. Both have medicinal herbs inside them, but the shape that has persisted through Haitian Vodou is the stem-on-globe shape. Minkisi had many different uses and were often associated with spirits, much like Haitian pakèt kongos. However, pakèt kongos are not filled with herbs or medicines, the bases of them are filled with soil from a graveyard or cemetery. They are “charged with spirits from underneath the land of the living” (Daniels 2013, 423). This core component is essential for the pakèt kongo to work at all.

The slaves that were in Haiti back in the late 1700s and early 1800s mainly came from Kongo and Benin. The slave revolution lasted from 1791 until 1804 and the slaves were aided by Polish troops that came with the French troops. Due to this Haitian Vodou was exposed to Christianity and Èzili Dantò was paralleled with Our Lady of Czestochowa, the black Madonna. Èzili Dantò is the fierce mother who will drop everything to protect her children, and she fought alongside the slaves during the revolution. She has two vertical scars on one of her cheeks, scars from an injury she received while fighting alongside her children. However, her children also betrayed her during the revolution because they thought that she couldn’t keep their secrets. This belief caused them to cut out her tongue so she could no longer talk. It is said that Èzili Dantò cannot see blood because “At the sight of blood, Dantò goes wild” (McCarthy Brown, 2010, 231). One point that is emphasized in texts about Èzili Dantò is that above all else, she is a mother and her children come first.

In Karen McCarthy Brown’s novel Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn, there is a story told by Mama Lola’s daughter, Maggie, about an experience she had with Èzili Dantò shortly after arriving in the US. Maggie got sick and had to go to the emergency room and the physician there thought she had tuberculosis and wanted to hospitalize her, but Maggie begged to go home. The doctor let her go home under the condition that she come back the next day for more tests. However that night:

We just went to bed, and then I saw, like a shadow, coming to the light… Next minute, I actually saw a lady standing in front of me… with a blue dress, and she have a veil covering her head and her face… she pull up the veil and I could see it was her with the two mark. Èzili Dantò with the two mark on her cheek… she told me to turn my back around, she was going to heal me… She rubbed my lungs and everything; she rub it, and then she said, ‘Now you know what to do for me. Just light up a candle and thank me.’… I went back to the doctor, and the doctor say, ‘What’s wrong with you? I thought you was sick!’ (McCarthy Brown, 227)

Èzili Dantò drops everything when her children are in need, without thinking twice. However, there is another side to Èzili Dantò that I mentioned briefly before. She is also known as Èzili of the Red Eyes and “some people call Dantò a baka (evil spirit)” because “Dantò can be evil, too… She kills a lot. If you put her upside down, you tell her to go and get somebody, she will go and get that person. If that person don’t want to come, she break that person neck and bring that person to you” (McCarthy Brown, 231-232). She is the warrior mother, the protector of single mothers, working women, abused women, and all her children. If she needs to be fierce, or if someone wants her to be evil, she will be.

The calm and intensity in Èzili Dantò’s personality are shown in her pakèt kongo through the blue and red colors that are present. The blue ribbon tied in a bow around the base is secured with pins, and the binding of the fabric isn’t just to keep the soil from getting out but “also to ensure that the spirit is kept in” (Daniels 2013, 423). As I mentioned before, there is a belief in Haitian Vodou that an illness or injury needs to be addressed both physically and spiritually. Pakèt kongos are used to help correct the imbalances in the cosmos through healing rituals. The one for Èzili Dantò is most likely used to pray specifically to Èzili Dantò for spiritual healing.

At the beginning of this project I wanted to learn more about Èzili Dantò just because of what I read about her in the little booklet next to the Haitian Vodou altar. That evolved into me wanting to know more about how the pakèt kongo on the altar represents her and how pakèt kongos are used in Vodou. I think I would need to see one used in a ritual to fully understand the ways in which they’re used in Vodou, however it is one of the most interesting objects I’ve ever studied. Haitian Vodou combines art with ritual and the pakèt kongo is a perfect example of that. The object appears incredibly decorative, but it does have a purpose, and one that is incredibly important. Seeing the object on an altar in a museum puts it out of context, automatically making it more difficult to understand the use of the object, it seems more decorative than purposeful. Art has power, and the exhibit gives that a new meaning, making it fitting that a pakèt kongo for Èzili Dantò be on the Haitian Vodou altar.

Bibliography

Daniels, Kyrah Malika. “The Undressing of Two Sacred Healing Bundles: Curative Arts in the Black Atlantic in Haiti and Ancient Kongo.”Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 3(2013):416-429.

McCarthy Brown, Karen. “Ezili.” In Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn, 219-58. University of California Press, 2010.

McCarthy Brown, Karen. “Afro-Caribbean Spirituality: A Haitian Case Study.” In Vodou in Haitian Life and Culture: Invisible Powers, 1-25.

Thompson, Robert Farris. 1983. “The Sign of the Four Moments of the Sun.” In The Flash of the Spirit, 119-127. Random House, Inc.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1-ndSaxwWzCmW7DPBxu_Grgikkb9FH_V5iLJKDVTP_Qw/edit?usp=sharing

The Spirited Things exhibit in the Fleming Museum is a lively display of altars and artworks from various Caribbean religions. The exhibit is erupting with color, wonder, magic, history, and life. Each piece was curiously unfamiliar to me, some more than others. It was difficult to identify the piece I was most interested in–there were dangling tassels, glittery fabrics, and bright colors at every turn. I was drawn to the Gelede Mask because of it’s quiet, powerful appearance. It contrasted with other objects in the exhibit in that it was not decorated in a particularly eye-catching way–it was composed of primarily earth tones, and its display was very simple and uncomplicated. It was standing alone in a minimalistic glass càs̩e̩, located in a section of the museum dedicated to items related to gender–a topic I take a special interest in. The mask displays a woman’s face, decorated with a snake wrapped around her head, and a warthog and hunter on the back side. This essay will explore the ideas that the Gelede mask is 1) an an active spiritual altar and 2) demonstrates the importance of women in ritual practices, while also raising questions about gender dynamics involved in such rituals.

The Gelede mask was created in July of 1983 for use within the Gelede festival in Nigeria–a spectacular ritual that pays homage to the spiritual powers of women. The powers possessed by such women are believed to influence the flow of good and bad events in practitioners’ lives, and can be used for the benefit/destruction of society. These powers are comparable to those of gods, spirits, and ancient ancestors of Yoruba peoples. Women (usually elders) who use their spiritual powers for destructive purposes are deemed witches in Yoruba culture. The Gelede ritual’s aim is to influence the witches to use their powers for good versus evil. Interestingly, men perform this ritual wearing masks that depict the faces of beautiful women. The Gelede festival includes costumes, music, singing, and dancing, and usually take place in a marketplace–the woman’s domain in Nigeria.

In the Gelede festival, women are the subjects of worship. Men dress as women and wear masks that imitate their faces:

The mask itself, then, is not the only element in these portrayals: in performance the male dancer imitates the movements of a woman. The young girls and women watch these embodiments of the feminine ideal, understanding that the conduct of the masquerade is what men desire of them. As Manuel Jordan suggests, however, “Women are willing to accept the female model presented to them by men if they agree that it represents them appropriately (Cameron 1998, 72).

Professor of history, art, and visual culture at University of California Santa Cruz, Elisabeth L. Cameron provides insights into the complex gender dynamics/relations within the Gelede festival. There are bound to be some interesting dynamics surrounding a ritual in which men “pose” as women in order to worship the spiritual powers of women themselves. The mask itself depicts a hunter on the back of the woman’s head. The hunter’s placement brings about some questions related to gender relations both in Yoruba culture and in the Gelede festival–does the hunter on the back of the woman’s head convey the idea that men are ultimately in control of these traditions? Within the context of this mask and ritual, it could also mean that men are at the mercy of women, as they worship and pray that their ritual will influence the witches present in their lives to use their power for the benefit of society instead of destruction. The Gelede mask is a meaningful and beautiful piece of artwork, but also functions as an altar within Yoruba culture. The rituals that this mask is used in give it the sense of life that African art is known for.

Spiritual altars in Yoruba cultures provide ways to call spirits, ancestors, gods, or other symbolic beings to a specific place. Altars are often adorned with beautiful decorations and offerings to various orisha (gods). Most often, altars are long tables or displays full of spiritual objects and vessels, some containing the essence of different orisha. The Gelede mask on display does not appear to be an altar in the traditional sense of the word–however, the Gelede mask functions as an active spiritual altar among Yoruba people who practice Gelede tradition. It’s purpose is, indeed, to call upon spirits of witches and attempt to guide or influence what they use their powers for. This type of altar is different than a traditional table altar, in that it is actively used in rituals rather than observed and simply used as a place to leave offerings and extend worship to the different orisha.