When I walked into the museum after being told about our project I already knew that I wanted to pick something on the Haitian Vodou altar. There’s something about Vodou that has always intrigued me. Maybe it was its misrepresentation in media that made me want to learn more about it, just like with my interests in Paganism and Wicca. That morning I walked into the exhibit and over to the Vodou altar I noticed objects and details that I hadn’t noticed when we had previously visited. I was drawn to multiple objects that had feathers on them, objects that my prior knowledge of African diasporic religions couldn’t help me understand. There was one specific object with blue and red feathers and an orb and stem kind of shape that caught my attention. Looking through the booklet next to the altar I found the object and read about it. It was a pakèt kongo for the goddess Èzili Dantò, protector of single mothers and abused women. At that point I didn’t need to look at any other objects, I knew I wanted to research Èzili Dantò and the pakèt kongo.

A pakèt kongo is a kind of container. The one I chose is primarily red and blue and is completely made of fabric, except for the feathers. It sits elevated on the altar, the blue and red striped base is full and held with a blue ribbon tied in a bow. Ribbons come out from the middle of the base, pale yellow and sticking up like bubbles on top of a drink. As my eyes move farther from the center, gold ribbons with a green pattern of flowers and squares and red ribbons embroidered with blue flowers and stems and gold trimming curl outwards giving the rounded base the appearance of a blooming flower. Protruding upward from the pale yellow ribbons is a stem wrapped tightly in red fabric. Two feathers extend from the stem, wispy and bent. The large red one grabs my attention first, but the smaller blue one demands to be seen too. An intricate kind of calm intensity surrounds the object, which was at first confusing but as I learned more about Èzili Dantò and about how pakèt kongo’s work, I began to understand its meaning, how it’s used in Vodou, and how it represents Èzili Dantò.

Many African diasporic religions have the belief that when someone is sick or injured the problem is not just physical; it’s also spiritual. It is usually thought that the problem occurred because whoever is sick or injured has fallen out of sync with the universe. The problem is then addressed ritually and holistically. In Haitian Vodou practitioners see doctors when needed, like for broken bones or serious illnesses, but the issue is still taken care of through ritual healing ceremonies in order to restore balance to the spiritual side of things. Most, if not all, of these rituals involve pakèt kongos.

The ancestor of the pakèt kongo is the nkisi, a healing bundle that comes from Kongo in Central Africa. There are minkisi (plural of nkisi) that have a kind of stem-on-globe shape, and then there are minkisi figurines. Both have medicinal herbs inside them, but the shape that has persisted through Haitian Vodou is the stem-on-globe shape. Minkisi had many different uses and were often associated with spirits, much like Haitian pakèt kongos. However, pakèt kongos are not filled with herbs or medicines, the bases of them are filled with soil from a graveyard or cemetery. They are “charged with spirits from underneath the land of the living” (Daniels 2013, 423). This core component is essential for the pakèt kongo to work at all.

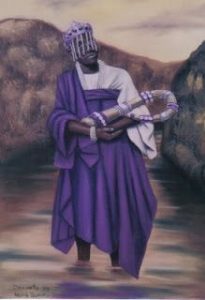

The slaves that were in Haiti back in the late 1700s and early 1800s mainly came from Kongo and Benin. The slave revolution lasted from 1791 until 1804 and the slaves were aided by Polish troops that came with the French troops. Due to this Haitian Vodou was exposed to Christianity and Èzili Dantò was paralleled with Our Lady of Czestochowa, the black Madonna. Èzili Dantò is the fierce mother who will drop everything to protect her children, and she fought alongside the slaves during the revolution. She has two vertical scars on one of her cheeks, scars from an injury she received while fighting alongside her children. However, her children also betrayed her during the revolution because they thought that she couldn’t keep their secrets. This belief caused them to cut out her tongue so she could no longer talk. It is said that Èzili Dantò cannot see blood because “At the sight of blood, Dantò goes wild” (McCarthy Brown, 2010, 231). One point that is emphasized in texts about Èzili Dantò is that above all else, she is a mother and her children come first.

In Karen McCarthy Brown’s novel Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn, there is a story told by Mama Lola’s daughter, Maggie, about an experience she had with Èzili Dantò shortly after arriving in the US. Maggie got sick and had to go to the emergency room and the physician there thought she had tuberculosis and wanted to hospitalize her, but Maggie begged to go home. The doctor let her go home under the condition that she come back the next day for more tests. However that night:

We just went to bed, and then I saw, like a shadow, coming to the light… Next minute, I actually saw a lady standing in front of me… with a blue dress, and she have a veil covering her head and her face… she pull up the veil and I could see it was her with the two mark. Èzili Dantò with the two mark on her cheek… she told me to turn my back around, she was going to heal me… She rubbed my lungs and everything; she rub it, and then she said, ‘Now you know what to do for me. Just light up a candle and thank me.’… I went back to the doctor, and the doctor say, ‘What’s wrong with you? I thought you was sick!’ (McCarthy Brown, 227)

Èzili Dantò drops everything when her children are in need, without thinking twice. However, there is another side to Èzili Dantò that I mentioned briefly before. She is also known as Èzili of the Red Eyes and “some people call Dantò a baka (evil spirit)” because “Dantò can be evil, too… She kills a lot. If you put her upside down, you tell her to go and get somebody, she will go and get that person. If that person don’t want to come, she break that person neck and bring that person to you” (McCarthy Brown, 231-232). She is the warrior mother, the protector of single mothers, working women, abused women, and all her children. If she needs to be fierce, or if someone wants her to be evil, she will be.

The calm and intensity in Èzili Dantò’s personality are shown in her pakèt kongo through the blue and red colors that are present. The blue ribbon tied in a bow around the base is secured with pins, and the binding of the fabric isn’t just to keep the soil from getting out but “also to ensure that the spirit is kept in” (Daniels 2013, 423). As I mentioned before, there is a belief in Haitian Vodou that an illness or injury needs to be addressed both physically and spiritually. Pakèt kongos are used to help correct the imbalances in the cosmos through healing rituals. The one for Èzili Dantò is most likely used to pray specifically to Èzili Dantò for spiritual healing.

At the beginning of this project I wanted to learn more about Èzili Dantò just because of what I read about her in the little booklet next to the Haitian Vodou altar. That evolved into me wanting to know more about how the pakèt kongo on the altar represents her and how pakèt kongos are used in Vodou. I think I would need to see one used in a ritual to fully understand the ways in which they’re used in Vodou, however it is one of the most interesting objects I’ve ever studied. Haitian Vodou combines art with ritual and the pakèt kongo is a perfect example of that. The object appears incredibly decorative, but it does have a purpose, and one that is incredibly important. Seeing the object on an altar in a museum puts it out of context, automatically making it more difficult to understand the use of the object, it seems more decorative than purposeful. Art has power, and the exhibit gives that a new meaning, making it fitting that a pakèt kongo for Èzili Dantò be on the Haitian Vodou altar.

Bibliography

Daniels, Kyrah Malika. “The Undressing of Two Sacred Healing Bundles: Curative Arts in the Black Atlantic in Haiti and Ancient Kongo.”Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 3(2013):416-429.

McCarthy Brown, Karen. “Ezili.” In Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn, 219-58. University of California Press, 2010.

McCarthy Brown, Karen. “Afro-Caribbean Spirituality: A Haitian Case Study.” In Vodou in Haitian Life and Culture: Invisible Powers, 1-25.

Thompson, Robert Farris. 1983. “The Sign of the Four Moments of the Sun.” In The Flash of the Spirit, 119-127. Random House, Inc.

The object was stuck in a falling state, suspended in mid air. A weapon among an altar, a scepter with crowns surrounding. I wanted to know where there was such a violent looking object in a place where everything else is full of color and life. The scepter does not stand out. It has little color and small designs that are worn away. The handle is simple, wooden staff. The kind of wood that if you held it, it would give you splinters. There are three brass segments on staff and right above the one at the top there is a cat like creature. It is a very interesting creature with a big cat body and long ears or horns. One of the biggest reasons why I picked this object is this animal and the shadow it casts. The shadow from the display makes it look like the cat is walking along the staff. Right before the axe head, two horns protrude, similar to the cat’s ears . There is the blade that is made of metal with tidal waves throughout the edge. Two metal pieces hold down the blade, an S shape metal piece and a spring piece. The last thing on the scepter is a flower a 6 petal flower below the horns and next to the head. On every other petal there are bumps that seem to make a simple pattern. This lead me to what I wanted to learn from this object. Why is this deadly object in a place of worship. Even within the scepter there are juxtapositions as there is a flower that draws your eye to it. I wanted to learn everything about this scepter and the god it represented, Hevioso or shungo. Contrary to its looks, it is not a weapon, it a tool used for religious and political festivals. I question the meaning behind with the aspects of the king and the deity he represented. As a hot god, Hevioso in vodou or Shungo in yoruba tradition, he does things quickly and people who have him as a deity are usually in power. This leads me to argue that this scepter was used to show power over the king’s followers. In the rest of the paper, I will give background on Hevioso and how a different king follows him and basic information on vodou and Yoruba tradition. Next I will talk about a king who was represented by the same god, Hevioso, King Glele and will then show how the scepter would be used in a festival based on first hand basis of people who research the religion. I will explain the cat creature on top of the staff and the significance it has towards the scepter.

The object was stuck in a falling state, suspended in mid air. A weapon among an altar, a scepter with crowns surrounding. I wanted to know where there was such a violent looking object in a place where everything else is full of color and life. The scepter does not stand out. It has little color and small designs that are worn away. The handle is simple, wooden staff. The kind of wood that if you held it, it would give you splinters. There are three brass segments on staff and right above the one at the top there is a cat like creature. It is a very interesting creature with a big cat body and long ears or horns. One of the biggest reasons why I picked this object is this animal and the shadow it casts. The shadow from the display makes it look like the cat is walking along the staff. Right before the axe head, two horns protrude, similar to the cat’s ears . There is the blade that is made of metal with tidal waves throughout the edge. Two metal pieces hold down the blade, an S shape metal piece and a spring piece. The last thing on the scepter is a flower a 6 petal flower below the horns and next to the head. On every other petal there are bumps that seem to make a simple pattern. This lead me to what I wanted to learn from this object. Why is this deadly object in a place of worship. Even within the scepter there are juxtapositions as there is a flower that draws your eye to it. I wanted to learn everything about this scepter and the god it represented, Hevioso or shungo. Contrary to its looks, it is not a weapon, it a tool used for religious and political festivals. I question the meaning behind with the aspects of the king and the deity he represented. As a hot god, Hevioso in vodou or Shungo in yoruba tradition, he does things quickly and people who have him as a deity are usually in power. This leads me to argue that this scepter was used to show power over the king’s followers. In the rest of the paper, I will give background on Hevioso and how a different king follows him and basic information on vodou and Yoruba tradition. Next I will talk about a king who was represented by the same god, Hevioso, King Glele and will then show how the scepter would be used in a festival based on first hand basis of people who research the religion. I will explain the cat creature on top of the staff and the significance it has towards the scepter.