Are people with mental illness more likely to commit crimes? This question has been studied and discussed for decades, fueled by movies of deranged serial killers. For years, the conventional wisdom was that, despite the hype, individuals who suffer from psychiatric disorders are no more likely than anyone else to commit a crime. More recently, however, there’s been a shift in that stance as increasing evidence points to the conclusion that, while the vast majority of those with mental illness do not break the law, the presence of psychiatric disorders is linked with higher rates of crime. Less is known, however, about children and adolescents, and a new report on adolescents provides  some useful data for clinicians to know and pass along.

some useful data for clinicians to know and pass along.

The study comes from National Comorbidity Survey – Adolescent Supplement which is one of our most important sources for epidemiological data on the community rates of adolescent psychopathology. This survey covers a nationally representative sample of 10,123 adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17. For this article, the key variables were the presence of a DSM-IV disorder as assessed using structured interviews with the adolescents directly as well as self-reported crime and arrest history. The average age was 15.

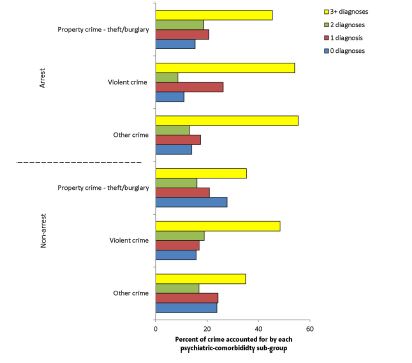

In terms of overall results, a total of 47% of the sample met criteria for at least one lifetime psychiatric disorder while 18.4% reported having committed some type of crime. Youth with psychiatric disorders were more likely to commit a crime, including violent crime, than those without psychiatric disorders. For crime resulting in an arrest, the largest elevations were, not surprisingly, related to conduct disorder (with an odds ratio of 57.5), as well as alcohol and drug disorders, but most other diagnoses were significant as well, including things such as anxiety disorders. In terms of percentages, the rate of violent crime resulting in arrest, for example, was 20.4% for those with a diagnosis of conduct disorder versus 0.4% among those with no diagnosis. The presence of multiple psychiatric disorders further increased the risk of crime. Excluding patients with conduct disorder weakened the link between psychopathology and arrested crime but less so for crime not associated with arrest. At the same time, over 88% of youth with at least one psychiatric disorder had no history of crime.

The authors concluded that the presence of mental illness raises the risk of crime. The authors advocate that these data should strengthen the case of good access to mental health care. Stay tuned for a summary about a study that documents a decrease in crime among at-risk children who received a comprehensive mental health program.

The major take away point from this study is both that 1) crime rates are elevated among adolescents with psychiatric disorders, and 2) the vast majority of those who meet criteria for a disorder do not report being involved in crime. Additionally, however, some side findings in this study were also interesting, like what’s up with the diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder (at 14.1%) being the second most common psychiatric disorder, while ADHD is a meager 4%. One also wonders the degree to which the self-report nature of the criminal behavior affected the results and the fact that many subjects were not yet through adolescence (both of which might have resulted in under-reporting).

Reference

Coker KL. Crime and Psychiatric Disorders Among Youth in the US Population: An Analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement. JAACAP 2014; 53:888-898.