Eli Van Buren

Cast to the back and to the side edge of the altar it appeared largely unimpressive standing next to the other, more flashy and colorful objects upon the altar to Yemaya. I think that is why it initially caught my eye. It appeared to be some sort of shell-covered model house, dust covered and a dull gray color from age. I’ve found that for the most part, some of the most discrete things turn out to be the most interesting. Naturally, I had to get closer to this dusty old box and as I did I realized it was quite a bit larger than I had first thought, about fourteen inches in diameter. It was almost totally covered in cowrie shells with a curious bird figure perched at the object’s crown. This was an Ile Ori, or House of the Head, a personal shrine dedicated to one’s own spiritual essence, individuality, and chosen destiny.

Ile Ori are hollow containers, usually with a cylindrical base and a conical lid. The Ile Ori wears scales of cowrie shells (an ancient currency among Yoruba peoples) which are symbols of great importance. The shells represent a triple meaning, as traditional currency they symbolize the riches of one’s good character; the overlaying cowrie shells allude to the feathers of a white bird; and the color of the shells, white, is the color of purity of character: iwa (Thompson 11). Commonly Ile Ori will even have a sculpture of a bird at the container’s apex. This bird is the eiye ororo or “bird of the head”

It is the bird which, according to the Yoruba, God places in the head of man or woman at birth as the emblem of the mind. The image of the descent of the bird of mind fuses with the image of the coming down of God’s ashe[spiritual essence that which embodies all things] in feathered form.

Thompson, 11

Moving on from the eiye ororo to other aspects of the lid, this particular Ile Ori has panels of alternating canvas, leather, and mirrors. Paired with the Ile Ori being specific to only one person, the mirror panels on two of the lid’s sides compound themes of individuality. Other materials were included in making the Ile Ori. Possibly the person’s placenta in addition to certain symbolic materials, such as clay, stone, or water (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27). Some objects represent different gods or oriṣa, depending on which oriṣa the person worshiped those materials would go into making the Ile Ori. Symbols appear to be an ongoing theme in Ile Ori and even the shape of the lid itself is of great importance. The cone has long been a symbol of humans and their place in the universe (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27).

Despite commonplace first appearances, this object has a hidden symbolism that transcends time to still be relevant today. Thinking of the Ile Ori as a personal altar will help understand exactly what the Ile Ori is. There is a common western idea of altars being entirely a raised platform upon which holy objects are placed. In understanding the Ile Ori, the concept of altars will expand to something greater. The Yoruba use altars in many things, and their altars come in many shapes and sizes. The Ile Ori is one such example, as the altar to oneself, celebrating individuality.

How can I begin to describe Ile Ori, the House of the Head, without first explaining the meaning of the head within a Yoruba context? Yoruba peoples, and those following Yoruba traditions, believe that one has two heads: an outer spiritual head (Ori Ode), and an inner spiritual head (Ori Inu). One’s outer head is physical, it was created with the body at birth. One’s inner spiritual head is much more complex, it contains a person’s iwa: their good (or in some cases bad) character, as well as the destiny they chose in heaven before descending to Aye: the world of the living (Thompson 11). The ori inu is also the site of one’s aṣe/ashe or life force. It is for this reason the Yoruba believe that inner qualities have a direct impact on the outer ones. This concept has been compared to a smoky flame: no matter how beautiful the smoke, inner ugliness will burn through, and vice versa (Thompson 11). In worshiping the head, heavy values are placed on one’s character. As an altar the Ile Ori functions differently in how it has a highly individualistic focus (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27). Centering around one person, each Ile Ori is only the shrine to one Ori.

There is no direct english translation for the word Ori. Ori can mean ‘head’, but it also means ‘destiny’, the two are interchangeable. The Yoruba have a strong belief in the concept of predestination and there are many words it is known by (Thompson 11). Though no matter the word used to describe predestination, it always comes back to be associated with Ori (Abimbola 115). People will visit a babalawo (diviner/fortune teller) to understand their chosen path in life through consulting their Ori and determine what it wishes of them. This practice is so universal that even the gods themselves have Ori guiding day-to-day life and will consult them from time to time for the same purpose (Abimbola 115). While the Yoruba believe in predestiny they also believe that each and every person chose that destiny. If someone is unsuccessful in life, it is largely due to the fact that they chose a poor head in heaven. So the head is a peculiar symbol of both free choice and predeterminism. The Yoruba even have proverbs describing the concept of Ori in this context:

Eni t’o gbon,

Ori e l’o ni o gbon.

Eeyan ti o gbon,

Orii re l’o ni o go j’usu lo

He who is wise,

Is made wise by his Ori.

He who is not wise,

Is made more foolish than a piece of yam by his Ori.

(Abimbola 114)

This sheds some light on how much impact Ori has on an individual. One of the worst insults one can be called is oloriburuku, which translates to “owner of a bad head”. To be called this is so offensive I probably should not have included it in this essay. It basically means that the offended is going nowhere in life and they chose to live a life of absolutely no worth. With such significance placed on symbols of the head, it really is no wonder this culture constructs altars dedicated to them. The Ile Ori is a way of prayer to appease their personal spirits as well as connecting with one’s inner spiritual self and their destiny (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27).

Nothing on or in an Ile Ori is there for no reason. Think about a modern western conception of an altar, each object or color has its specific symbolism or meaning. The Ile Ori is an altar, a shrine to a god named Ori. Ori is the god of the self. In some ways, Ori is the most important deity in the Yoruba pantheon (Abimbola 114) for it is respected as a personal god, and owned by a single person. Each person’s Ori belongs to them and it is understood that they will be more interested in personal affairs than the other gods, who are owned by all people (Abimbola 114). In worshiping their Ori people will place objects within the Ile Ori in order to please their Ori. It is in this manner the Ile Ori is given life, it becomes an aṣe-infused object with a very active role in a person’s life.

Opposed to other Yoruba, Vodou, Santeria, or Christian altars where everything is clearly visible and open to all people, the Ile Ori is a private altar. It is very unique and personal to a single individual, and so it is an altar closed to the prying eyes of others. Objects are placed inside the altar instead of upon it. The object placed within is called iponri. Iponri is a vital figure containing elements of one’s ancestor spirits, potential restrictions in life, and the oriṣa. This iponri is “everything that plays a significant role in the life of the person.” (Drewal, Pemberton, Abiodun, 27) This proposes a new definition of what an altar is. Objects and offerings are placed within, not only to appease their Ori, but to improve their own destiny. A Yoruba proverb speaks of the constant human struggle on earth, stating that most humans chose poor Ori, poor destinies, in heaven. Through life people struggle to achieve the impossible goal of improving their predetermined bad destiny (Abimbola 146).

As a personal shrine, the Ile Ori challenges what I previously thought of as classified as an altar. Altars need not be dedicated to gods, oriṣa or spirits. The Ile Ori has shown me worship is dynamic and unconfined to being directed towards higher beings. As an altar, this object channels aṣe/energy towards the self. It beautifully balances self-love with self-improvement within a spiritual symbol. The Ile Ori tells us to purge bad character yet still appreciate yourself, to be happy with you lot in life yet still work to improve it. Through studying this Ile Ori my concept of altars has expanded. As an altar so centralized around individuality, it is very different than other altars, which have the effect of bringing people together. The Ile Ori introduces a rarely seen, yet vastly important, spiritual form; that of self worship.

“Òwèrè là ńjà”: we are only struggling

Abimbola 146

Drewal, Pemberton & Abiodun, The Yoruba World. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New

York, (date needed), pp. 26-33

Abimbola, ‘Wande Ifa: An Exposition of Ifa Literary Corpus. Oxford University Press Nigeria,

Ibadan, 1976, pp. 113-147

Thompson, Robert F., Flash of the Spirit. Random House, Inc., New York, 1983, pp. 11

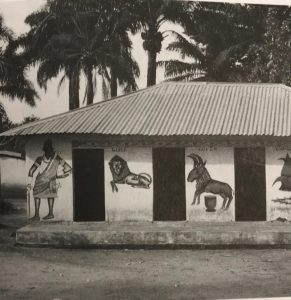

(picture from the Spirited Things website)

(picture from the Spirited Things website) (picture form the Spirited Things website)

(picture form the Spirited Things website) (picture taken by Alyssa Falco)

(picture taken by Alyssa Falco)