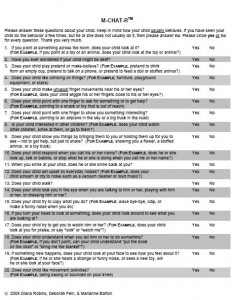

When it comes to autism screening for toddlers, the Modified Checklist for Autism (M-CHAT) is one of the most widely used and studied instruments available (and it’s free and dowloadable). While it’s been shown to have both good sensitivity and specificity, there is always room for improvement. Thus was born the M-CHAT Revised with Follow-up (M-CHAT-R/F).

What makes the new scale different is not just some changes in the wording of some of the questions but, perhaps more importantly, how the M-CHAT is scored and categorized. Now, based on what parents write down on the M-CHAT-R/F, the total score is placed into one of three categories – low, medium, and high risk. What to do for the low and high risk toddlers is pretty straightforward. Those at high risk should be sent for a more in-depth autism evaluation right away and those at low risk don’t need further action, other than a repeat M-CHAT-R/F if they are not yet 24 months old.

The middle risk kids are a bit trickier. Now, the instructions are that primary care clinicians are supposed to go through a series of scripted questions that delve into more detail about those items that are raising a red flag for autism. Such a process could take about 15 minutes or so and potentially could be done by someone other than the physician. Based on those questions, another score is generated and if that score is also above the cut-off then the full evaluation is recommended.

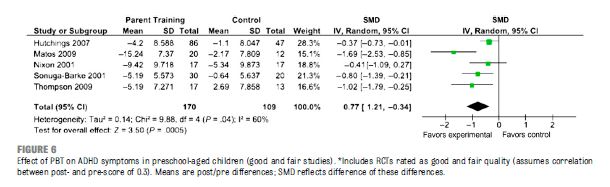

A recent study of over 16,000 toddlers who presented for well-child checks at 18 and 24 months of age demonstrated the utility of the new instrument. Nearly 93% of the initial M-CHAT-R scores were negative, defined as a score of less than 3. Of those screening positive, 63% of them no longer screened positive with the follow-up assessment. After establishing an optimal cutoff point of three for the M-CHAT-R and then at least 2 for the follow-up, those who remained positive were found to have a 47.3% chance of being diagnosed with autism, with only 5% of the remaining sample assessed to be developing typically. This detection rate of autism was found to be superior to that of the original M-CHAT.

The million dollar question in my mind, however, is will this new step for immediate risk really happen in a busy primary care office, and what will occur if it doesn’t?

In the published study, it is important to point out that they didn’t ask the PCPs to do that follow-up piece: the research staff did. This leaves the open question of how feasible it is to ask the primary care community to do these. Interviews containing scripted questions to help make a diagnosis of various psychiatric disorders have been around for decades and are considered “gold standard” measures that are required in research studies. However, they are uncommonly used in everyday practice by psychiatrists and even more rarely used in primary care settings. Consequently, it seems quite likely that many primary care clinics will struggle with this new recommended step. Am I wrong here?

I was so curious about this aspect that I sent an email to the lead author of the M-CHAT, Diana Robins PhD, at George State University. She replied quickly and acknowledged that this is looking like a real problem. In fact, she’s is having trouble finding PCPs willing even to participate in a study about putting the new M-CHAT into practice.

If primary care clinicians decide not to adopt this new follow-up procedure, the instrument could lose some of its discriminative power. If that happens, a number of things could occur.

- Primary care clinicians could just stick to the old M-CHAT (with the loss of the improved instrument resulting in less accurate autism detection)

- They could plan to do the follow-up step but often not actually get to it (resulting in a delay of the screening process)

- They could group the medium risk kids into the low risk group (which potentially could result in some autistic kids not being formally evaluated until they are older)

- They could group the medium risk kids into the high risk group (which could lead to more evaluations and longer waits for kids who would not end up being diagnosed with autism but require formal evaluations to verify this)

None of these options seems ideal and my guess at this point is that the incorporation of the new M-CHAT will be quite slow, especially with this new step in place. Public health officials interested in autism screening might begin to look for a system that will work without making it too arduous for those who need to implement it.

If you are a primary care clinician that does autism screening, please feel free to comment on what you do now and what you plan to do about the new M-CHAT, if anything. This one might be worth some follow-up dialogue on how we best should do things around here.

Reference

Robins, DL, et al. Validation of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised With Follow-up (M-CHAT-R/F). Pediatrics 2014;133:37–45