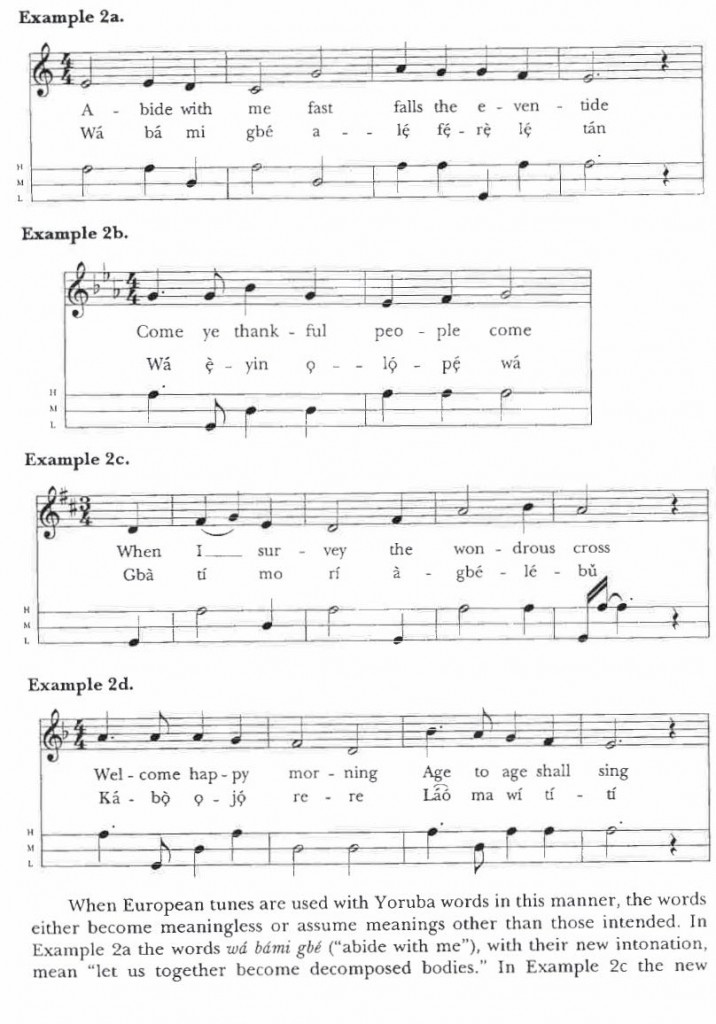

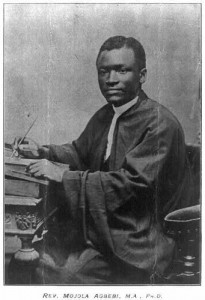

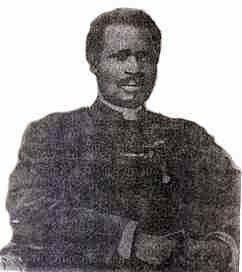

This post will be the final one on my research on Yoruba gospel music. It has also been the most difficult to write. In part, this is because I want (need?) to be more speculative and abstract in my discussion of the recordings of Yoruba Christian songs made by the Reverend J.J. Ransome-Kuti in London in 1927. My previous posts have been based on the historical and musicological sources that I have been able to find concerning Kuti’s life and music. In Part 2 I looked at how Kuti’s biographers positioned him as a Christian pioneer who mediated between old and new in colonial Nigeria. In Part 3, I discussed how Kuti’s musical compositions resolved a problem of musical translation for early Yoruba Christians; namely, the tone-tune issue where the tonal aspects of Yoruba language clashed with the musical melodies of translated European hymns. Today I want to return to some of the questions I raised in my first post and to ruminate on the issues and further questions raised by my investigation into these recordings.

As you may recall, I am especially interested in the recordings themselves and the issues concerning technology and materiality that they raise for our understanding of Yoruba Christianity. These questions speak to wider concerns in anthropology, African studies, and the study of Religion: the place and contributions of colonized Africans in the making of our modern world, the role of sound technologies in transforming religious and cultural practices,and the transformations of the senses—in ways of hearing and soundings—by recording technologies which enabled a new way of transmitting and circulating sounds.

While I can’t address all of these issues directly here, I want to reflect a bit on the phonograph, a technology central to the story I have been telling so far. There are numerous scholarly writings about the place of the phonograph in the shaping of modern experience and conceptions of music in particular and sound more generally. A key theme in these writings has to do with how recordings enable sounds to be dislocated and disembodied from their original sources, resulting in what R. Murray Schafer has termed “schizo-phonia,” a term with which he meant to indicate the troubled nature of such a relationship between sound and source. A similar strain may be found in the critical writings of Theodor Adorno, who in 1934 wrote of the phonograph record as designating a “two-dimensional model of a reality that can be multiplied without limit, displaced both spatially and temporally, and traded on the open market.” Thus, for Adorno music becomes less about technology serving human needs and desires, but rather about the subjection of humans to things, and the reduction of music to an object that can be bought and sold, thus transforming human history and experience.

While I can’t address all of these issues directly here, I want to reflect a bit on the phonograph, a technology central to the story I have been telling so far. There are numerous scholarly writings about the place of the phonograph in the shaping of modern experience and conceptions of music in particular and sound more generally. A key theme in these writings has to do with how recordings enable sounds to be dislocated and disembodied from their original sources, resulting in what R. Murray Schafer has termed “schizo-phonia,” a term with which he meant to indicate the troubled nature of such a relationship between sound and source. A similar strain may be found in the critical writings of Theodor Adorno, who in 1934 wrote of the phonograph record as designating a “two-dimensional model of a reality that can be multiplied without limit, displaced both spatially and temporally, and traded on the open market.” Thus, for Adorno music becomes less about technology serving human needs and desires, but rather about the subjection of humans to things, and the reduction of music to an object that can be bought and sold, thus transforming human history and experience.

More recent writings on the phonograph have complicated these arguments, seeking to uncover the assumptions about the nature of sound, music, and hearing that underlie them. For example, Jonathan Sterne in The Audible Past outlines the history of the possibility of sound-reproduction in order to show how many of our now taken-for-granted ideas about sound and human experience emerge in relation to sound-reproduction technology itself; so that, for example, the universal primacy of face-to-face human interaction which is assumed in arguments such as Schafer’s is actually a historical and specific set of ideas that emerge out of an engagement with sound technologies. Other writers have considered the ability of sound technologies to repeat and circulate sounds outside of their original contexts in the formation of racial categories and subjectivities. For example, the role played by the phonograph in colonialism, particular in the kinds of racial imagination and desires enabled by the technology have been discussed by writers such as Michael Taussig and William Pietz. Alexander Weheliye considers the creative possibilities of sound-reproduction technologies as enabling of black cultural production and productive of a “sonic Afro-modernity” that entails new modes of and new possibilities for being.

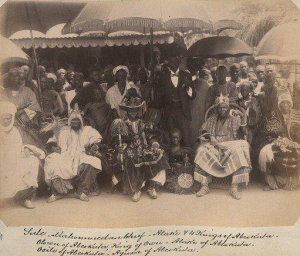

Placing the technology of the phonograph recording at the center of the story I am telling here shifts priorities, questions, and possible conclusions. For example, why is it that Kuti’s biographers merely mention the fact of the recordings rather than emphasizing them as part of his mediation between old and new? Certain events, such as Kuti’s challenge to Yoruba traditional authority through the desacralizing of the umbrella, or his encouragement of the Christian ogboni as an Africanization of Christianity, receive detailed, chapter-long treatments in Delano’s biography. In contrast, the recordings are only briefly mentioned, in Chapter Nine of the book entitled “In Remembrance” which describes Kuti’s efforts at maintaining the church in the context of the loss of independence of the Egba nation to the colonial government. Delano writes of the recordings in a single sentence, which appears in a paragraph documenting Kuti’s travels outside of Nigeria. Here is the paragraph in its entirety:

In 1922, by the kind munificence of the late Mrs. J. B. Wood, one of the early European missionaries, he visited the Holy Land. By invitation of the CMS Authority he travelled through Europe, and attended the CMS Exhibition in London. He took this opportunity of making some gramophone recordings of his songs. This was his second visit to London; the first had been in 1905, when he preached in St. Paul’s Cathedral. On his return form his travels he was made a Canon of the Cathedral Church of Christ, Lagos. [emphasis added to original.]

That’s it?! Really? This is the only mention of the recordings in a 64-page text about Kuti’s life. Of course, this passing mention might be understood in relation to Delano’s purpose in writing the book, which is to cast Kuti as a pioneer of Christianity among the Yoruba, and as an influential figure in the transformation of Egba society from old to new. Delano thus dwells mainly on Kuti’s activities in Egbaland, suggesting, perhaps, that the recordings had very little influence on Yoruba Christian life in Nigeria beyond the fact of their being made.

Extending this line of argument to the tone-tune issue discussed by musicologists, Kuti’s recordings then are also a document of his resolution of this issue in his compositions. Furthermore, as Akin Euba notes, it is one that has little impact on Yoruba Christian practice; as Euba writes, “ironically…the sings which today appeal most popularly to the grassroots of the Christian community…are songs in which the intonation of the words is often distorted, as if they were European hymns translated into Yoruba and sung to European tunes.” So much for Kuti’s impact on future Yoruba Christian musical production, whether through the printed hymn book or the recordings.

Further support for the lack of importance or impact of the recordings in Nigeria is provided by the journalistic website Sahara Reporters, in an article about “The Singing Minister: The unsung story of Fela’s grandpa.” Here Kuti is depicted in reference to his grandson, Fela Kuti, the contemporary Afro-beat superstar whose life and music has been the subjects of numerous books, films, and even a Broadway play. The article about the “unsung story” of J.J. Ransome-Kuti provides the (apocryphal?) tale of Kuti’s grandson, Dr. Olikoye Ransome-Kuti, learning of the existence of the recordings from a librarian at the British Library. Olikoye is reported to have been “shocked to listen to his grandfather’s voice, not in Abeokuta, his ancestral home, but right in far away British Museum.” Certainly a displacement of object from source, a voice calling out across the generations. Could it be that Rev. J.J. Ransome-Kuti’s recordings really had so little impact in Nigeria that they were lost even to his family members?

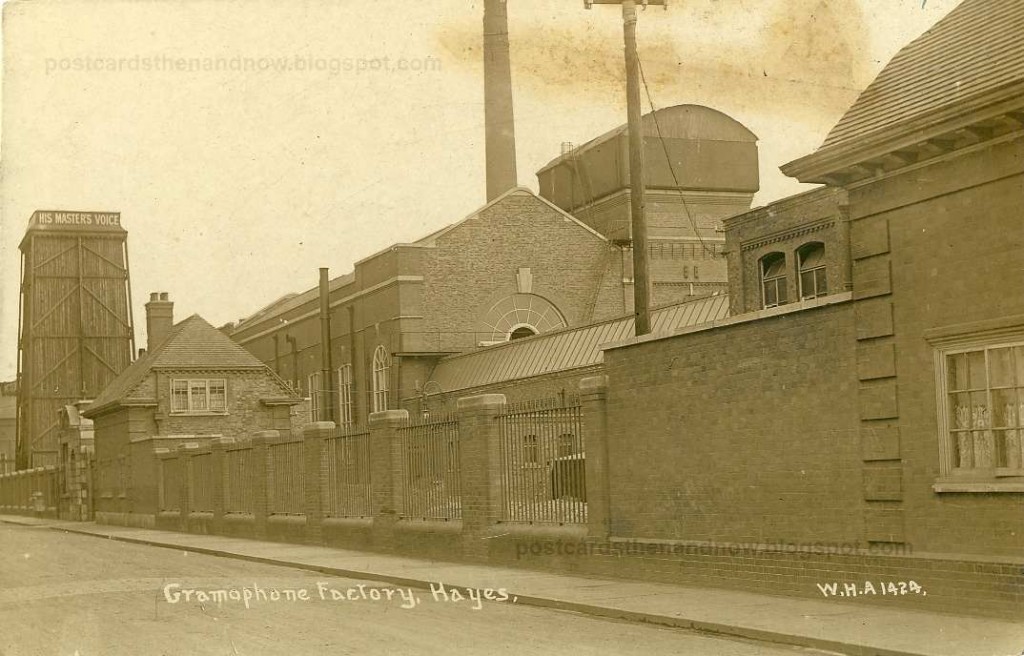

EMI Factory; Hayes, London; c.1914. From the blog Postcards: Then and Now

Coming at this issue from another direction, there is the possibility that the recordings were made for European audiences and that it was there where their impact lay. Recall that Paul Vernon suggested that these records were “aimed at a European audience and regarded as novelties.” I dismissed this possibility in my first post, but now I want to reconsider it. Indeed, a number of novelty recordings of Africans and other colonial subjects were made for sale in European markets, though the majority of them were of folkloric songs or performances. Some recordings featured speakers of African languages demonstrating the diversity of human linguistic output. Other recordings were distinctly ethnological, intended to preserve aspects of local cultures that were seen as disappearing in the face of European colonialism.

Thinking about the recordings in this way opens up a number of new analytic questions: What does it mean to think of Kuti’s recordings as a novelty for European listeners? What did that even mean; in other words, in what way were they a novelty? Why might European listeners want to hear a Yoruba man sing his Christian songs in a language that they could not understand? How did these recordings impact British understandings of the colonial project and of the place of Africans in British conceptions of Christianity?

While I do not have the answers to these questions, they present fruitful avenues for further research into this topic. My intention in this series of posts has been to describe my current research and to provide insight into the research process. My posts make clear that the research process is often messy and incomplete, requiring one to move forwards and then back again as the researcher’s categories are refined and her questions reformulated. While I hope that you have enjoyed learning more about the recordings made by J.J. Ransome-Kuti, I also hope that you have learned a bit more about the nature of research in the humanities (and the humanistic social sciences). This is the reason why my series of posts on this topic ends with more questions than answers. As the sociologist Andrew Abbott writes:

In the humanities and social sciences we do not ask questions to to which final answers already exist, answers which can be found somewhere. We seek to adjust the questions we can ask and the answers we can find into harmonious writings that explore again and again the subtleties that constitute human existence. It is our pleasure to do this in a rigorous and disciplined way. That is what makes our research academic. But our research is not scientific, for the things we wish to discuss do not have fixed answers. We discover things, to be sure, but their discover merely opens further possibilities to complexify them.

evance of work by UVM faculty, students, and alumni. It featured a number of Religion Department faculty!

evance of work by UVM faculty, students, and alumni. It featured a number of Religion Department faculty!

I have an almost-two year old daughter, and she has a legion of Nanas, Pop-Pops, Grandmas, Grandpas, Aunties, Uncles, and general well-wishers who love buying things for her. (This is lovely and appreciated, even if often roundly met with frustration: Please bring less stuff into my house. Please.) In the midst of a now-typical “But, seriously, what does she need?!” conversation,

I have an almost-two year old daughter, and she has a legion of Nanas, Pop-Pops, Grandmas, Grandpas, Aunties, Uncles, and general well-wishers who love buying things for her. (This is lovely and appreciated, even if often roundly met with frustration: Please bring less stuff into my house. Please.) In the midst of a now-typical “But, seriously, what does she need?!” conversation,