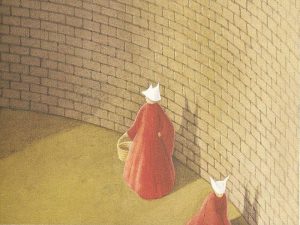

Recently a colleague put together a dystopian fiction reading group. We get together and discuss how speculative narratives of a terrible future can illuminate our lives under a president that many fear will make our present reality leap forward into that future. The first book we discussed is Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, a dystopia that takes place in the near future in nearby Cambridge, Massachusetts. The book appeared in 1986, when I was in high school in Boston (and two years after 1984 had us all thinking about Orwell’s dystopic future). I read Atwood’s book a few years later, in college, and haven’t returned to it since then, so this was a welcome excuse for me to re-read it. In addition, I had just finished re-reading Atwood’s Year of the Flood because I had assigned it to my class: “Religious Perspectives on Sustainability.” (After all, what is “sustainability” but a story we tell ourselves about the future?) So I looked forward to reading The Handmaid’s Tale again in light of her more recent work and after so many of my own formative years have intervened.

The Handmaid’s Tale depicts a society in the grip of a theocratic tyranny. Religion in the book is wholly negative, a thing of control, hypocrisy, and fear. The Year of the Flood is part of a series of novels called the “MaddAddam Trilogy.” The first book, Oryx and Crake, was published in 2003, The Year of the Flood in 2009, and the final book, MaddAddam, in 2013, so they are much more recent and the product, perhaps, of a more mature author. Somehow during those years between 1986 and 2003, Atwood has maybe not let go of her judgment of religion (or people who profess to be religious), but made her critique of it less vitriolic, and at the same time broadened her depictions of religion to incorporate hope and love as well as fear and hate.

The irony is that the epilogue at the end of The Handmaid’s Tale leaves the reader with a more hopeful sense of the future — that the religious unmaking of society and re-making of it into something inhumane and literally barren — is only a blip in human history, a short and distasteful meandering off the path of if not progress, at least social stability. In a way, this negating of the horrific consequences of theocracy works to emphasize how wrong and powerless those who seek to rule that way actually are. It also makes sense of the way the book is somewhat one-dimensional: the society she creates has no history and no future, like a laboratory experiment that cannot be moved outside of its controlled environment. However, in our reading group we agreed on the chilling realism of how the state easily took control of the financial sector, making it impossible for women to control their own money, and how this combination of technology and patriarchal ideology so effectively subjugated half of the population in a matter of hours.

In MaddAddam, all of American (and Canadian, and in fact the entire global) society is implicated in Atwood’s dystopia, and the destruction goes far beyond the social world, infecting the animals, plants, and earth itself. Yet the group that manages to survive the “waterless flood” does so at least in part because of their ability to embrace religious rituals, worldviews, and morality, creating a blend of ecological science and Christianity that they form into a religion that literally works to save their lives. They value the effects of ritual to bond people together, the meditative practices that cultivate a sense of connectedness between humans and non-human beings like bees or pigs, and the mantra-like performance of recitations that allow them to remember the past and the heroes of the earth, like Rachel Carson and Jane Goodall. Although not all of the members of the religion “believe” in it, their practice of it reflects not hypocrisy, as it does in The Handmaid’s Tale, but a pragmatic and realistic embrace of religion in spite of doubts and skepticism.

These differences give us insight into how authors of speculative fiction can reflect the fears and concerns of their times. While The Handmaid’s Tale focuses on the growing power of evangelical Protestant Christian males to control women’s bodies, lives, and even minds, in MaddAddam the “bad guys” are scientists and business people, who seek to control the genomes of humans, animals, and plants, with little thought for a future beyond the deposit of profits into the bank account.

In the 1980s, “Liberal” America (and Canada) was grappling with a perceived sudden re-animation of a politically active conservative Christian voting bloc and culture. The prevailing narrative of the preceding decades among the “mainline” Protestants told of a growing ecumenicalism, an assumption that religious practice and choices should be private, and the embrace of a civil religion that was bland enough to accept any and every “god” and yet religious enough to distinguish us Americans from the “godless Communists.” (See Robert Bellah, and Will Herberg) Sectarianism – the championing of one version of Jesus over any other – or even any public Jesus talk at all, was unseemly, especially for someone in an elected position. John F. Kennedy had given his speech, almost unthinkable today, denying that his religious commitment would influence his actions as president.

In 1980 all three candidates for president professed themselves evangelical Christians, a clear sign that the religious narrative was changing. With the election of Ronald Reagan, the so-called moral majority gained a public voice and began a struggle, from the school-board level on up, to gain political ascendancy. The Equal Rights Amendment had failed to pass. The perceived progress made in racial justice left feminists of all races feeling that identity politics downplayed gender in favor of elevating male leadership in movements like the Black Power Movement. The triumph for women’s rights of Roe v Wade came under attack, and the anti-abortion movement began to gain a more vocal platform. It began to inspire individuals to threaten and carry out attacks on clinics where abortions were performed. Operation Rescue was formed in 1986, with an explicitly Christian rationale. It is easy to see how Atwood can find a dark inspiration in the news stories of the day.

Likewise, in our contemporary era, where news and social media are filled with stories of genetically modified crops that reap massive profits for global agri-corps who sell both the seeds and the pesticides that they are engineered to resist, and drug companies creating designer drugs that exist solely to replace previous drugs now available in cheaper generic forms, and oil companies proclaim their commitment to a “green” future while seeking government subsidies to pull ever dirtier fossil fuels out of the ground, it is easy to see where Atwood’s inspiration for the MaddAddam series comes from. However, the way she depicts religion in these books has become more humane and humble in the case of the God’s Gardeners, and funnier in the case of the oil-based version of Christianity that one of her characters runs afoul of during the course of the story.

Although the future is bleaker in The Year of the Flood, Atwood’s own vision of humans and the religions they create and embrace seems more open to both the mystical possibilities of a world without clear-cut moral answers, and to the way religion can be a powerful force for human resiliency in the face of civilizational collapse. The Year of the Flood can speak satisfyingly to both the religious seeker and the anthropologist. Its dystopic vision reflects how our fears have changed, from threats to religious freedom to threats to the continued existence of humanity, and perhaps even the earth itself. Personally, I’m very glad to have Atwood’s characters demonstrate a way to persist with grace, grit, and humanity, with or without religion.