As an undergraduate student at the University of Vermont (UVM) my academic career has taken quite a few turns, to say the least. I came into the University as a Political Science student, who aced her AP Government and Politics Exam in high school, and who totally “felt the Bern.” Looking back on what I wanted, I thought that I would now have two political internships and months of campaign work under my belt, ready to be a staffer for some big, up-and-coming name in American Politics. Who knew that a class called “What is the Bible?” (of all things) with Professor Anne Clark would change this.

What I aim to discuss in this context is how the Liberal Arts “saved me,” or—to make it less dramatic—challenged me to learn differently. What I mean by this, is that taking this singular class that discusses arguably the most popular book in the world’s history opened my eyes to a new way of learning that I never found in my Political Science courses. I am not saying that one field is better than the other, but actually that they bolster one another to give me rich, foundational, and holistic knowledge on issues I deem important.

As I have advanced in my academic career at UVM I have taken a wide range of courses, which include international relations, political ideology, Islam’s place in modernity, as well as the nexus of religion, the nation, and the state. The topics I just listed have been taught in both of the departments I am currently in: Religion and Political Science. However, the messages and methods to go about learning these topics was dependent upon whether or not it was a Political Science or Religion class. I did not realize this until I reached higher-level courses, which allowed me to better challenge the knowledge thrown at me rather than simply absorb it. During one of our classes in “Religion, Nation & State,” Professor Borchert said something that stuck with me: “our disciplines make us blind to certain things.”

Within the field of Political Science, I have become quite interested in the topic of international relations. In Religion, I have spent much of my time and energy on the study of Islam(s). Here, I aim to discuss these two topics and how they are constantly intertwined, as well as how they have been made to have this type of dichotomy with one another. If I only studied Political Science, I would have never come to terms with how Islam is consistently homogenized, racialized, and even seen as a “foreign policy concern,” which will be better understood once Elizabeth Shakman Hurd and Cemil Aydin are brought into this discussion later on. If I only studied Religion, I would not have been able to put the pieces together to discern why U.S. Foreign Policy in particular has been failing when it pertains to topics involving Islam. This personal example of mine is exactly why interdisciplinary thinking is essential for tackling the world’s most complicated and multifaceted problems. Therefore, in the rest of this blog post, I aim to demonstrate how interdisciplinary thinking when used in international relations, specifically in relation to Islamic studies, has the potential to make a real-world impact that is positive and ever-lasting.

Critiquing the Norm

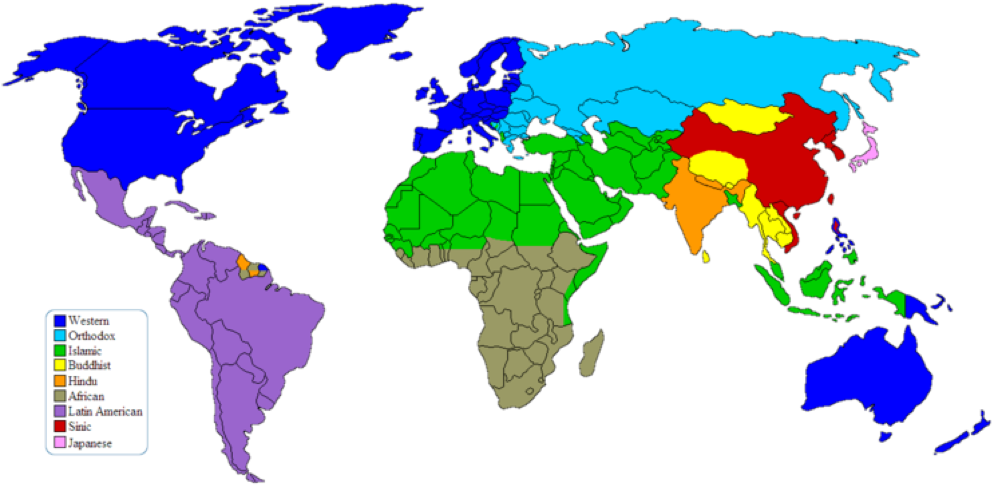

I remember the first time I was taught Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations?” piece in my Middle Eastern Studies class in high school. My teacher showed us the map that portrays Huntington’s thesis, which uses a ‘cultural’ approach to understanding the world’s divisions, and therefore carves up the world into a set of “civilizations.”[1]

When I got to college, this same map and thesis was explained in my Intro to International Relations class, to showcase what the state of our world was after the end of the Cold War. Then, I entered into my Introduction to Islam class, which did not focus on his thesis in a fundamental way at the beginning of the semester, like other courses. Rather, his argument was brought up later in the semester to further denounce the notion that Islam is a monolith civilization, among other critiques. Finally, in my Political Islam course, Huntington’s “Clash of Civilization’s?” was the first academic work listed in the syllabus.

What exactly am I trying to prove here? The consistent importance, precedent, and normalization of a scholarly work, which has been detrimental to the lives of people all over the world as a result of its rhetoric.

There is a plethora of academic works that denounce and thoroughly critique the thesis that arguably made Huntington the most prominent scholar in his field. To begin, Cemil Aydin, a historian, questioned in his book titled The Idea of the Muslim World, “Why has the idea of the Muslim world become so entrenched, despite the obvious naïveté of categorizing one and a half billion people, in all their diversity, as an imagined unity?”[2] The entire purpose of Aydin’s book is to debunk Islam as a monolith, and especially as a “civilization,” as Huntington puts it.[3] This homogenization of an entire religion leads to stereotyping, among other more detrimental consequences. Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, a political scientist who studies religion, emphasizes in Beyond Religious Freedom that we need to “understand the world that is being created when the category of religion is privileged as a basis for developing foreign policy.”[4] This is another unfortunate outcome of the ways in which the power given to Huntington’s thesis has deeply impacted how we think of the global community and the factions within it. Having “Islam” and the “West” juxtaposed as civilizations that oppose one another encourages foreign policy to base its actions off of gross generalizations and assumptions. All in all, it’s quite obvious just from these two examples that the “Clash of Civilizations?” is problematic and unhelpful in fostering good policy and ideologies.

This poses my next question: why? Why did several of my classes cite Huntington in their syllabi, and spent time during lecture discussing his argument? This is not just a trend among UVM courses, but this is a nationwide, American expectation that Huntington be used in syllabi when Islam and politics are intertwined. Take for instance the American Political Science Association (APSA), which claims that it is the “leading professional organization for the study of political science.” The APSA recommends that whenever international security and terrorism are taught, that Huntington’s piece should be cited and used. This is dangerous, to be quite frank. It is not enough to cite Huntington, and spend an entire class period debating on whether or not he should be credited for his thesis. Including “The Clash of Civilizations?” as the first academic work on a syllabus gives it power, prominence, and makes it to be seen as fundamental to the course being taught. Students in such classes will continuously cite his work and will think that his name is worthy to remember. This only reaffirms the several consequences as stated above.

A Well-Needed Reality Check

I would have never been able to come up with such conclusions if I had only stuck to Political Science courses. I would have never realized how fundamentally wrong Huntington is if I had just taken Religion courses. Hopefully it can be seen as to why I spent several hundred words denouncing “the Clash of Civilizations?”—to showcase what the Liberal Arts is capable of doing: provide interdisciplinary ways of thinking that challenge the norm. It’s because of this that I am better able to raise my hand in lecture and push back on what is being taught to me. It is because of this that I am able to look at syllabi in a critical manner. It’s because of this that I am a worthwhile candidate for the work force once I graduate—because I understand the value of a Liberal Arts education.

Let’s take this a bit further, and expand upon what should be fixed to recover from the mistakes that have been made in U.S. Foreign Policy. To go back to Hurd’s thesis in Beyond Religious Freedom, she cites that we must use “three heuristics” to go about how we discern religion in an international context. These are “expert religion, lived religion, and governed religion,” and each emphasizes “a different set of themes and topics that are important to the argument as a whole.”[5] In my opinion, most of what we discuss in international relations focusses on expert (religious leaders, academics, and other professionals speaking about religion) and governed (state officials, heads-of-state, and representatives) religion. Therefore, what gets missed is probably the most important viewpoint of all: the lived lives of everyday people. Lived religion is characterized as being “practiced by everyday individuals and groups… to navigate and make sense of their lives, connections with others, and place in the world.”[6] If I ever enter into a foreign policy career, my advocacy and attention will hold this concept to the highest standard. Decision-making at the highest level tends to focus less on the individual and more on the entirety of a nation-state. Proper training in the Liberal Arts can thus offer holistic approaches to how we should handle international dilemmas.

Do I have faith in the notion that most other 2020 college graduates will have the same realization about their education? Not quite. The Political Science Department is one of the biggest at UVM, while Religion is one of the smallest. Also, other Universities such as the University of Connecticut do not offer a Bachelor’s degree in Religion, which I easily could have gone to being a Connecticut resident. The access as well as the choices I have made throughout my college career have allowed me to advance my knowledge in this subject. I have no doubt in my mind that my path would have been immensely different if I had never become a Religion Major.

What is at stake here is plain and simple: the inability for those such as myself, who are wildly passionate about international policy and conflict, to comprehend what sources of knowledge are sustainably damaging. This is a cyclical issue that feeds into higher systems of power and influence, which have real-world consequences. Cohorts of undergraduates that get placed into work forces that directly work with relevant topics should understand what I am understanding. The means of critically assessing knowledge must be made more accessible, as well as digestible. Shorter books such as Hurd’s that are made purposely for experts in relevant fields, blog posts and other short mediums of knowledge production; can hopefully bring about more critical reasoning in the field of foreign policy, such as my own realization of Samuel Huntington.

To put the cherry on top of this discussion, I would like to thank the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Vermont for encouraging me to take that class about the Bible my very first semester at this institution. Three years later, and I can say that I actually learned something.

[1] Samuel P. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Affairs 72, no. 3 (1993), 23

[2] Cemil Aydin, The Idea of the Muslim World: a Global Intellectual History, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), 2.

[3]Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations?” 31.

[4] Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, Beyond Religious Freedom: the New Global Politics of Religion (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), xii.

[5] Hurd, Beyond Religious Freedom, 9.

[6] Hurd, Beyond Religious Freedom, 9.

Work Cited

Aydin, Cemil. The Idea of the Muslim World: a Global Intellectual History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Bucar, Elizabeth M. Pious Fashion: How Muslim Women Dress. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-77, edited by Colin Gordon.

Huntington, Samuel P. “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Affairs 72, no. 3 (1993): 22–49.

Hurd, Elizabeth Shakman. Beyond Religious Freedom: the New Global Politics of Religion. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Kurzman, Charles, and Carl W. Ersnt. “Islamic Studies in US Universities” in Middle East Studies for the New Millennium: Infrastructures of Knowledge. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Lewis, Bernard. What Went Wrong. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Mahmood, Saba. Politics of Piety: the Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Masuzawa, Tomoko. The Invention of World Religions: or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Morgenstein Fuerst, Ilyse R., and Zahra M. S. Ayubi, eds. The Muslim World; Special Issue: Shifting Boundaries. 4th ed. Vol. 106. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2016.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.