Last September I announced on the REL@UVM blog that I would post periodic updates about what I was up to while on sabbatical. I then disappeared…into my field notes, stacks of library books, and pages of notes on my new book project. Well, I am back! I am still in the thick of it—ordering books from Interlibrary Loan, searching through indexes to find out which archives might hold relevant sources, and scribbling and typing notes on what I know and what I need to find out. This month I plan to share some of these notes in a series of posts describing my current research and providing some insights into the research process.

The main project I have been working on since September has been a study of commercially recorded and distributed Yoruba gospel music. This topic emerged naturally out of my research on music in Cherubim and Seraphim churches in Lagos, as the church where I based much of that earlier research had a choir that released a number of successful recordings (see my article about these recordings here). My interest in the gospel music industry in southwest Nigeria led me to investigate the history of this genre. When were the first recordings of Yoruba Christian music made? How? Who made up the audience? Do the recordings circulate today?

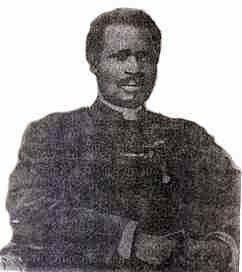

These questions led me to focus on what I believe are among the earliest—if not the earliest—sound recordings of Yoruba gospel music. In 1922 the Reverend Josaiah Jesse Ransome-Kuti traveled from his home near Abeokuta, Nigeria to London, England to attend the Church Missionary Society Exhibition. While there, he recorded a total of 43 songs which were released on double-sided Zonophone discs by the Gramophone Company.

According to most sources, Ransome-Kuti wrote and arranged all of the songs he recorded. The recordings feature Ransome-Kuti singing to piano accompaniment. The majority of the songs are described on record labels as Yoruba “hymns” or “sacred songs.” In addition to these Christian songs he also recorded a funeral lament, and a track described on the label as “Abeokuta National Anthem,” a folk song about the strength of the Egba Yoruba community in which Ransome-Kuti lived.

I first heard these recordings when I visited the British Library in 2010. However, they have since been released by Bear Family Productions on a monumental boxed set called Black Europe that documents the sounds and images of black people in Europe prior to 1927. The set includes 45 discs of music and data, along with two coffee-table books that provide documentation and background information about the recordings. While only 500 copies of the Black Europe set were released, when I asked Lori Holiff, the librarian at UVM’s Bailey-Howe Library, to purchase a copy she readily agreed. In the past three months I have been poring over the recordings and combing through the extensive documentation to help me understand the significance of these recordings for both the history of Yoruba Christian music as well as for the development of the music industry in Nigeria.

I have a lot of questions to ask of these recordings. It is unclear exactly why they were made and how they were used. In a paper concerning the history of the recording industry in West Africa, Paul Vernon suggests that the Ransome-Kuti recordings were likely novelty records made for British audiences. I have a difficult time imagining non-Yoruba speaking listeners to these recordings, nor does this explanation account for the number of songs that Ransome-Kuti recorded. A more promising explanation is found on a promotional sheet reproduced in the Black Europe book, which notes that the recordings were made by Ransome-Kuti “so that the Sacred Songs of his own composition…may be available to all Yoruba speaking people” (Vol. 2, p. 194) This statement opens up the possibility that they were recorded for and distributed to the growing number of elite, educated, and Christian Yoruba families in Lagos and Abeokuta, Nigeria in the 1920s. This group constituted an early market for Western commodities, which may very well have included gramophones. I am looking for additional evidence that supports this interpretation. I still have to follow the strands through the archives and history books to determine to what extent the playback technology was available for consumers in Nigeria in the 1920s and 1930s and whether or not recordings such as those made by Ransome-Kuti were marketed to listeners in Nigeria.

I am also interested in how these recordings were used, and what people thought about them at the time. Did they help to circulate the growing corpus of Christian songs composed by Yoruba musicians to the expanding number of churches in the Yoruba-speaking region of the colony? If so, this represented a transformation in the way Christian practices were circulated between churches. Were the recordings intended to help congregations learn these songs so that they could sing them during church worship? Did they supplement the numerous printed hymnals and other song books in which the songs appear?

I do not have the answer to these questions though I have some ideas about what I will find, as well as some ideas about the implications my findings will have for understanding the development and significance of Yoruba Christian music. In the coming weeks I will tell you more about what I have found out about J.J. Ransome-Kuti and these recordings, how my research questions have developed over time, and what new directions this project will take me towards in the future.

Read Part 2 of this series of posts, “Ransome-Kuti: Between Old and New.”