Last Thursday, I received an anti-Islam, anti-Muslim flyer titled “Islam vs. Democracy” at my campus office address. I’d been mailed the same flyer during the Spring semester, as well. At that time, I responded by holding a class session in my REL096: Islam course in which we analyzed and critiqued the two-sided flyer, line by line, in the theoretical terms we’d explored all semester (Orientalism, imperialism, authenticity, categorical definitions) and compared to the definitions for Islam we’d read by scholars (like Ernst, Shepard, and Curtis, to name a select few).

It was a challenging class. Most students were horrified–one actually gasped out loud, another approached me after and apologized, having done nothing wrong, for the existence of such material. Many students expressed genuine feelings of disgust and exceptionalism: UVM is a friendly, liberal place, they said; this shouldn’t have happened here. Some asked questions about the role of open spaces and free speech on a public campus; others asked if free speech rules applied on a campus and to whom; and others still asked about the overlapping issues of free speech and campus safe spaces, accommodations, and UVM’s On Common Ground ideals. We solved none of these problems of a contemporary campus broadly or of our own.

But, in April, near the end of the term, so many of my students–even some who rarely spoke in class–offered real critique of the content of the flyer, citing theorists of religion, scholars of Islam, and critics of both. We read the flyer as a primary source to be interrogated, analyzed, and placed in its multiple contexts (what kind of literature was this? who or what was its audience? what do we do with unsigned writings? where was its information factually wrong? to what avail? & etc.).

That was my response this past spring. I scrapped a class about American Muslims in the earliest part of the 20th century so that we could instead talk about a two-sided flyer found on campus for an hour. We applied what we’d learned about Islam, the study of religion, and reading primary sources critically to a new primary source document–the flyer itself. We had an academic conversation first, but also addressed the affective responses it elicited, which ranged from thinking the flyer a joke unworthy of our time to tears, frustration, and anger.

This time the flyer surfaced, however, students hadn’t yet arrived. I sent out a call on Twitter and my personal Facebook account asking if anyone else had seen these flyers. Two colleagues responded that they had seen them in Williams Hall both recently and back in April. I’d found another set of flyers postered in Bailey-Howe Library, and a student sent a direct message on Twitter to say he’d seen them in the Davis Center, a center of student activity (and food) on campus.

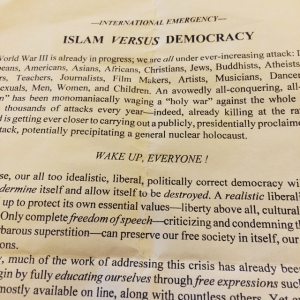

I won’t republish here the anti-Islam, anti-Muslim diatribes beyond this (purposefully incomplete) photo. There are lots of responses to Islamophobic content, in the broadest senses; and there are responses to those responses. There are books, journals, blogs. I am not a scholar of Islamophobia, and I am deeply aware of the various risks publishing about it can be. The broadest sense of all this isn’t the point, anyway. It is the peculiarity.

I won’t republish here the anti-Islam, anti-Muslim diatribes beyond this (purposefully incomplete) photo. There are lots of responses to Islamophobic content, in the broadest senses; and there are responses to those responses. There are books, journals, blogs. I am not a scholar of Islamophobia, and I am deeply aware of the various risks publishing about it can be. The broadest sense of all this isn’t the point, anyway. It is the peculiarity.

In this context, a broad post I might write about how anti-Islam, anti-Muslim rhetoric actually limits engagement on a campus by using fear is too general. It feels like a general response to a general phenomena on campuses writ large. But this wasn’t a general flyer, out there somewhere. This was a flyer on our campus, right here.

These flyers certainly speak about a vast, faceless, dangerous, and imagined Islam, but because they appear on campus, they are directed at us, the members of the UVM community–Muslim and non-Muslim alike. Moreover, because it has been mailed to me personally (but not to my departmental colleagues), I can assume I am a targeted audience for the message of the flyer, and I might further imagine this is specifically in my capacity as the professor of courses about Islam and Muslims in the Religion Department.

So, my response is this: a lament that students arrive in our classrooms today, August 31, and that my classes won’t begin until tomorrow.

Had these flyers gone up in a week, I’d have a clear sense of what my job is, what my obligations are, in terms of my campus. I’d ask students to talk about it. We’d read it, in the constructed space of a classroom which is purposefully set up for interrogation, investigation, and critique. We’d take its claims seriously, talk about where they came from, and what work they do now; we’d maybe theorize why UVM’s campus–why the library, the student-centered Davis Center, Williams Hall, and my mailbox–were imagined to be good spaces for an anonymous poster and author declare “the truth” about Islam in the form of double-sided, photocopied flyers. We’d talk about the possibilities, responsibilities, and challenges of free speech on campuses. We’d talk about reading about religion beyond classrooms, and the value of the skill sets needed to do so. We’d talk about microaggressions and safety for our classmates, colleagues, and staff who were the subject of the flyer’s message. We might even place this flyer in a conversation about Muslims and racialized religious identity–a conversation we normally get to toward the end of the semester.

My classes begin tomorrow. And my syllabus has already changed.