When Prof. Brennan issued a call-for-posts about what we were reading, I assumed I’d write about something serious and scholarly: what I’m reading for class (currently: Durkheim in REL100) or for my research (currently: Meer’s edited volume on racialization, religion, antisemitism, and Islamophobia) or as part of attempting to keep up with the field (next on my list: Aydin’s brand-new book on “the Muslim world”). Yet as I sat to write my post, I kept coming back to what I was reading that was serious, but perhaps not as scholarly: two books, Rad American Women A-Z and Rad Women Worldwide by Kate Schatz and Miriam Klein Stahl, have been in constant rotation as part of my regular reading routine with my nearly-4-year-old daughter. The truth is, these books are rather serious, rooted in scholarship, and speak to what I’ve been thinking about broadly in and outside my classroom and as part of my research.

This won’t be the first time I use our academic, departmental blog to talk about what is ostensibly children’s literature. It also won’t be the first time I try to convince my reading audience that children’s literature isn’t only for children, doesn’t only communicate childish ideas or ideals, and needn’t be compartmentalized to my parenting. In fact, I’ve found that both of these volumes have driven home simple–but not basic–ideas about representative parity in my research and pedagogy, the importance of the study of religion (and its regular absence as we talk about radical activisms), and how the act of reading is itself political.

We bought Rad American Women A-Z for my daughter a couple of years ago. She loved it. Big, bright, graphic illustrations helped; the alphabet as a central motif didn’t hurt; I assume my excitement about each and every featured woman¹ didn’t hurt, either. She really loved this book. (As in, my 2.5-year-old daughter insisted that she be “P is for Patti Smith, the punker” for Halloween.) The book itself features American women that represent a wide swath of historical periods, racial and ethnic identities, as well as expressions of gender and sexuality. The women represent diverse fields and aims, too, ranging from athletes to education activists, doctors to musicians, architects to strike leaders. Poignantly, “X” is reserved for the “the women whose names we don’t know,” a purposeful acknowledgment of the erasure of women in historical memory and contemporary settings alike. I’ll confess to weeping nearly every time I read this page.

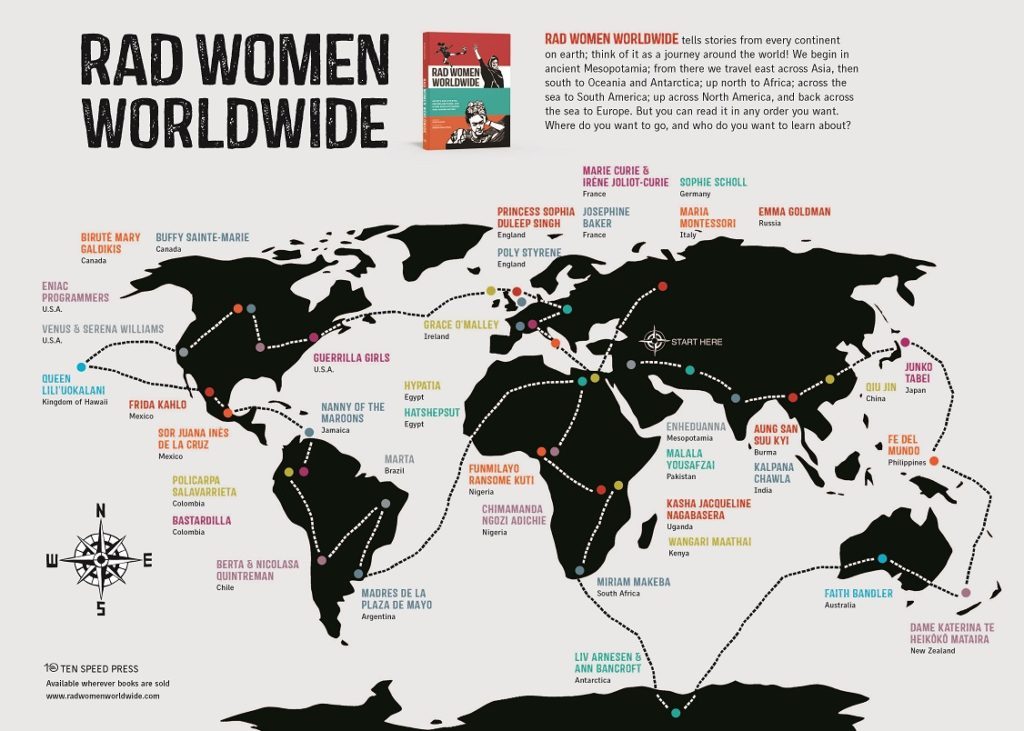

When Rad American Women’s sequel came out last year, we added it to our rotation. Rad Women Worldwide takes an even larger historical scope, starting in “ancient Mesopotamia” and including contemporary, notable women like Malala Yousafzai. These women, too, represent multiple regions, eras, races, ethnicities, mother tongues, and areas of excellence. They include LGBTQ+ activists like Kasha Jacqueline Nagabasera,

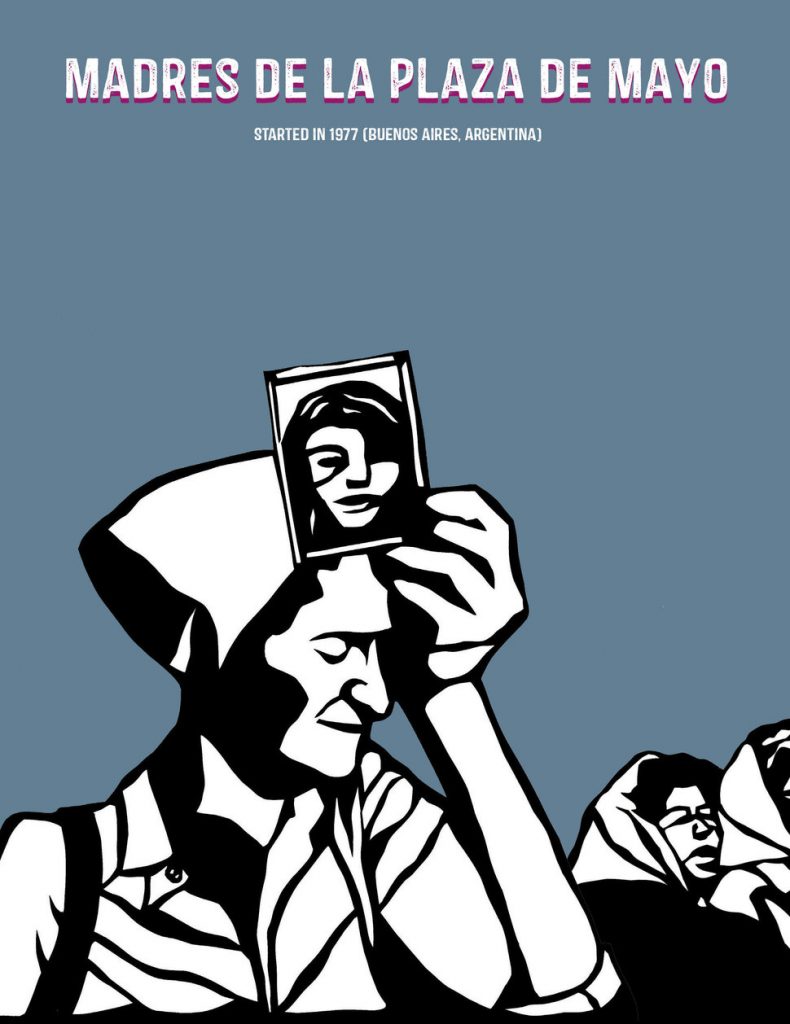

anti-authoritarian women’s organizations likeMadres de la Plaza de Mayo, athletes like Junko Tabei, and anti-colonial, anti-imperial native activists like the Quintreman Sisters. Like the original volume, Rad Women Worldwide includes a poignant entry that jolts the reader into seeing the silenced; here, it is titled “the Stateless,” and focuses on the disproportionate number of refugees who identify as women. Like “X” in Rad American Women, “the Stateless” is a hard page to read without choking up.

anti-authoritarian women’s organizations likeMadres de la Plaza de Mayo, athletes like Junko Tabei, and anti-colonial, anti-imperial native activists like the Quintreman Sisters. Like the original volume, Rad Women Worldwide includes a poignant entry that jolts the reader into seeing the silenced; here, it is titled “the Stateless,” and focuses on the disproportionate number of refugees who identify as women. Like “X” in Rad American Women, “the Stateless” is a hard page to read without choking up.

Reading these two books with my kiddo has meant admitting to her and myself how few women–American or not–I had ever learned about. I have considered myself both a feminist and an activist for my whole life. I’ve done my gender courses. Heck, I’ve even taught them. And yet, it is a shocking realization to have only heard of many of the featured Americans and not recognize even a third of the “global” women. (And, yes, of course, my own identity is at play here: a cis-hetero-white-Jewish-lady may have heard of Emma Goldman [of course!] but not of Filipino doctor Fe Del Mundo [I had not].)

Reading these books regularly–often just a few full entries at a time–also underscores the lack of gender parity in my syllabi and bibliographies for published work. Following the lead of many other scholars, most of whom identify as women, I have tried to make a point to have women not only represented in my syllabi–sadly, a feat in and of itself at times–but to have women represented in a way that reflects women’s participation in the academic production of knowledge. Which is to say, #noallmalesyllabi and #noallmalebibliographies. Schatz and Stahl go to great lengths to remind their readers that for every woman they’ve included, dozens and dozens have been excluded by their authorial choice, or as “X” and “the Stateless” remind us, by systemic and intersectional oppressions.

So these books remind me, in their simple composition, to ask: who am I leaving out? Which systems of purposeful omission am I participating in when my citational practices are heavily white, heavily male? How can I fix that–or, more to the point–how can I fix that so I do not preserve and reproduce sexist, racist trends in the writing of history and production of knowledge? After all, I think: my daughter is listening to me read, watching me model how to make sense of these rad women.

These books also remind me that when we talk about activism, we often ignore religious foundations for that activism. While Schatz and Stahl do a genuinely incredible job of showcasing women in their complexities, the presence of religion is largely absent–even in activists and historical personas for whom religion was a primary motivator. For example, the Grimké sisters, abolitionists who are oft-read in American religious history courses for their use of Biblical literature, are described as Quakers but their activism is not described in terms of their religion. As a scholar of religion, it seems an obvious omission and beyond begging the obvious question (where is religion?) such omissions beg questions about our conceptualizations of secularism, activism, and (perhaps assumed) progressivism.

I’m reading a number of books simultaneously like a good professor ought. In fairness, I also read a ton of silly books made for kids with my daughter that I slog through and attempt to sound excited about. These two books, though, ostensibly aimed at a younger reader (though, admittedly, perhaps not a not-quite-4-year-old), aren’t just for kids. These two are well on their way to becoming dog-eared and well-worn parts of our family library. As I read them aloud, I am often thinking not only of how radical it is to simply be reading to my daughter about powerful women whose lives represent an imperfect fullness of human identity and expression. I am also thinking about how much more they underscore the ways I need to continue to strive for representative parity in my research and pedagogical bibliographies, the ways in which religion is somehow omnipresent and absent when we think about radical activisms and activists, and how the act of reading–aloud or otherwise–is always already a political act. The books that center this kind of reading, both with and for my kiddo, will be on my reading list for the foreseeable future.

- *”Woman” and “women” in these works indicate those who identify as women. We can infer this based upon Schatz and Stahl’s inclusion of trans* and GNC women.