A new report prepared by Change Healthcare for the Department of Vermont Health Access documents a sharp drop in the number of Vermont Medicaid-insured youth who are prescribed psychiatric medications. The report stems from a project called Improving the Use of Psychotropic Medications among Children and Youth in Foster Care. Vermont is one of six states involved in the project.

Some of the highlights include the following for Vermont Medicaid-insured youth not in foster care.

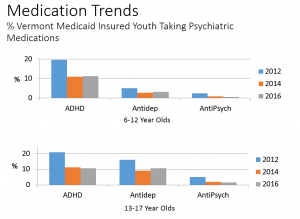

- Between 2012 and 2016, the percentage of youth taking at least one psychiatric medication dropped by about 42% for both the 6-12 age group and the 13-17 age group. In 2016, approximately 13% of Medicaid insured youth from the ages of 6-12 had taken a psychiatric medication in the past 6 months while for adolescents in 2016 the percentage was just under 20%.

- For all age groups, ADHD medication usage dropped by about half.

- Antipsychotics, a class of medications that many clinicians worry about most, had the biggest drop in prevalence, falling 74% in the 6-12 year old age group. This class of medications continued to drop between 2014 and 2016 while for ADHD medications and antidepressants, the rate was relatively stable across the last 2 years after a more pronounced drop between 2012 and 2014.

While the usage of many types of medications across many age groups dropped, there were some exceptions. For example, as ADHD medication usage among children under age 6 dropped between 2012 to 2016, the rate increased among those in foster care, although this was due to a very small number of children. At the same time, antipsychotic usage among very young children in foster care dropped from 1.1% to 0.3%. Overall, psychiatric medication usage among children in foster care continue to be much higher compared to kids not in foster care, although for many ages and medication classes there appeared to be a modest drop between 2012 and 2016.

The million dollar question, of course, and one that the report does not attempt to answer, is what might be behind these drops in usage. Most likely, the trends are due to a combination of factors some of which are more newsworthy than others. There were increases in the number of kids enrolled in Medicaid during this time and shifting demographics of the new enrollees could have been a factor. There also, however, appears to be a change in culture with clinicians becoming more cautious about medications while trying to emphasize non-pharmacological treatments and wellness activities.

Another important question is whether or not all of these decreases are a good thing. Most people, including myself, generally interpret these findings as positive, but the numbers alone can’t tell us the degree to which these usage decreases represent a more balanced approach to child emotional-behavioral problems versus the reduction of treatment among those who need it. Further study is planned with these data to understand more fully what may be occurring and why.