At our clinic at the Vermont Center for Children, Youth, and Families, one unique component of our child psychiatry evaluations is the provision of also assessing mental health problems in the parents, using validated rating scales. This element was included in the face of mounting data showing that successful treatment of psychiatric disorders in parents can result in behavioral improvements in their children. Now, a recent study adds some new wrinkles to this issue while giving clues about how this effect might work.

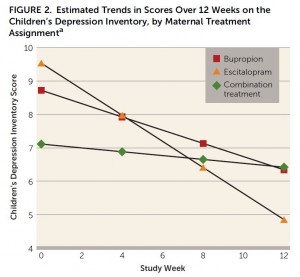

The study is a randomized double-blind 12 week clinical trial for 78 mothers with clinical depression that compares two different antidepressants and their combination. One group was treated with buproprion (Wellbutrin) only, one with escitalopram (Lexapro) only, and another group treated with their combination. Behavior problems in their 135 children, ages 7 to 17, were also assessed. Additionally, parenting behavior and maternal negative affectivity (guilt, hostility/irritability, anxiety) were also evaluated.

Treatment of the maternal depression was relatively effective with remission occurring in 67% of the sample. There were no significant differences in remission between the treatment groups. However, the association between improvement in the mothers’ symptoms and improvement in their children’s depressive symptoms and functioning was significant for mothers in the escitalopram only group. In examining possible mechanisms for the child improvement, there was some evidence that mothers in the escitalopram group had improved abilities to listen and communicate with their kids. The children in this group corroborated the mothers’ report by noting greater maternal care and affection with treatment. Further, child scores improved among mothers with high levels of negative affectivity again for patients in the escitalopram only group but not for the other groups.

The authors concluded that the effect of children’s behavior improving as their mother’s depressive symptoms improve may depend of the type of treatment. They hypothesized that treatments that improve maternal anxiety and irritability may be especially helpful through their effect on parenting.

In discussing their results, the authors admit being somewhat surprised and puzzled with why the escitalopram only group seemed to fare better than the other two groups when it came to child behavior. It also is important to note that this study does not imply that medications should be the sole focus of treatment for depressed parents, as another study found similar benefits when using interpersonal therapy (one of the evidence-based psychotherapies for depression). Also worth noting is that this study was conducted before the FDA warning on ecitalopram that recommend not exceeding a dose of 20mg. In this study, patients received as high as 40mg.

In summary, this study nicely helps connects the dots between changes in maternal symptoms, changes in child symptoms, and possible mechanisms for this effect through modifications in parenting behavior. For primary care clinicians, it is important to ask about emotional-behavioral problems in parents when evaluating children. Family physicians may particularly be in prime position to help their child patients by addressing the mental health concerns of the parents.

Reference

Weissman M, et al. Treatment of Maternal Depression in a Medication Clinical Trial and Its Effect on Children. Am J Psychiatry 2014, epublication ahead of print.