The benefits of Omega-3 supplementation has been touted for a wide range of therapeutic and health promotion uses. While there is emerging data for problems such as ADHD, the literature has still suffered from issues such as small sample sizes, lack of randomization, short duration, and lingering questions about optimal dose. This recent study sought to address some of these limitations using a randomized double-blind placebo controlled design and studying children for a total of 12 months, which included 6 months of study after the supplementation ended. Another innovation for this study was the additional measurement of parent behavioral problems, under the notion that these could  mediate improvement in child behavior.

mediate improvement in child behavior.

The nonclinical sample included 200 children from the ages of 8 and 16 from the island nation of Mauritius. For those of you without a PhD in geography, this is a small island in the Indian Ocean off of Madagascar (yes I had to look it up too). Half of the sample was radomized to receive 1 gram of Omega-3s (300 mg of DHA, 200 mg of EPA, 400 mg of alpha-linolenic acid, and 100 mg of DPA) delivered in a fruit drink while another 100 received a fruit drink without the Omega-3s. Behavior problems were measured by parent- and child-report at baseline, at the end of the six month study, and at 12 months, using our favorite instruments the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Youth Self-Report, supplemented with other measures of aggression. As mentioned, an interesting aspect of this study was that rating scales were also given to parents to examine their own levels of psychiatric symptoms both at baseline and at follow-up.

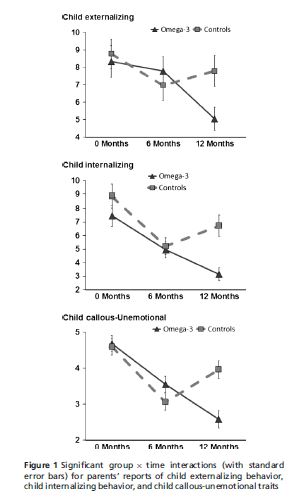

The main finding was a significant effect for omega-3 supplementation across a wide range of parent-reported child behavior. Improvements were found not only in the predicted areas of aggression and externalizing problems but also for internalizing problems such as anxiety and depressed mood. The changes for child self-report behavior were less dramatic but present for things like both reaactive and proactive aggression. Indeed, even the troubling and hard to treat callous-unemotional traits showed improvement by parent-report. For many measures, significant differences were mainly apparent at the 12-month interval, six months after the trial ended, thus emphasizing the need to stay with treatment over a long period of time. Overall, externalizing behavior decreased 41.6% six months after the trial ended compared to a drop of around 11% for placebo. The overall effect size was found to be moderate (d=-.59).

Also extremely interesting and providing further evidence for a family-based approach to child mental health is the finding that parents also showed reductions in measures of their own psychiatric symptoms (even though they weren’t taking the supplements). Furthermore, improvement in parental symptoms was found to substantially mediate the improvement found in the child’s behavior. An impressive 60.9% of the improvement in child antisocial behavior, for example, could be attributed to reductions in the parents’ reduction in psychopathology.

The authors concluded that their data provide support for the utility of using omega-3s to reduce both internalizing and externalizing behavior and suggest that one mechanism through which children get better is that their parents improve with regard to their own psychopathology.

In my mind, this is an important study in many ways and I’m surprised it wasn’t covered more widely. This may have been because it was published in a certainly reputable but not very prominent journal. What is remarkable about this study is not only the fairly robust improvement noted with Omega-3 supplementation but also the demonstration of how important it can be to improve parental symptoms in the pathway of improving child behavior.

At the same time, some limitations are worth noting. The sample was non-clinical and the authors did not examine whether or not more symptomatic children responded to the Omega-3s the same way that less symptomatic children did. Also, there obviously will be some questions about how generalizable this sample is coming from a fairly remote island. Finally, it needs to be said that the commercial company that provided the Omega-3 drinks, a Norwegian company called Smartfish, supported this study financially, and it is important that we give that fact the same skeptical eye that we would apply if we were talking about a prescription medication study supported by a pharmaceutical company.

Nevertheless, these results are important and add to the growing body of research suggesting that Omega-3s should be on our radar screen as clinicians. The specific dose is also helpful as a guide.

Reference

Raine A, et al. Reduction in behavior problems with omega-3 supplementation in children aged 8–16 years: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, stratified, parallel-group trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014, epub ahead of print.

Tags: aggression, callous-unemotional, omega 3