Are children and adolescents in the United States too easily given psychiatric medications? There has been a lot of attention to this question lately with many people both within and outside of the mental health community believing that the answer is a resounding yes. Yet while there is ample evidence suggesting that the percentage of youth taking psychiatric medications is rising, there remain fewer data that weigh in on the question of whether those who meet criteria for a psychiatric illness have been saturated with too much treatment. Into this debate comes an important study by Merikangas and colleagues from the National Institute of Mental Health that was recently published in the journal JAMA Pediatrics.

The data from this study comes from the National Comorbidity Survey – Adolescent Supplement. The participants are a nationally represented sample of over 10,000 adolescents between the ages of 13 and 18 who were assessed directly at home or at school for the presence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorder using a structured interview. Medication usage over the past year was also assessed.

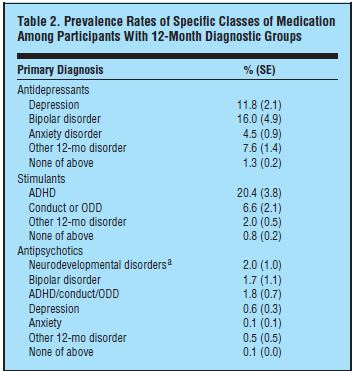

Results showed that of youth meeting criteria for any psychiatric disorder, only 14.2% were taking a medication in the past 12 months, with only approximately a quarter receiving any mental health services. The types of medication participants were taking reflecting the nature of their disorder, although rates of medication usage tended to be low for all disorders. A total of 20.4% of youth with a diagnosis of ADHD were being treated with stimulants, while 14.1% of adolescents with a mood disorder were taking an antidepressant. The rate of antipsychotic usage was found to be 1.0% and was generally being prescribed for those with developmental disorders. The proper correspondence between type of disorder and class of medication was found to be more common among youth in the mental health system in comparison to those in general medical care. Looking at the flip side, only 2.5% of adolescents who did not meet criteria for a psychiatric illness had been given a prescription medication.

The authors concluded that the vast majority of youth with mental disorders are not being treated with psychiatric medications. They argue that their study challenges the common perception that youth are being overprescribed psychiatric medications.

After reading this study, the rates of medication usage in this study are amazingly low. Perhaps some subjects previously were taking medications but no longer were due to side effects or poor response. Others have questioned the claim that this sample truly is nationally representative with a concern that lower SES groups may be underrepresented (who also tend to have higher rates of medication usage). In the end, however, it is undeniably true that there exist children both who could benefit from medication but don’t take it in addition to those who take medication but don’t need it. Our efforts might be best utilized by trying to reduce both of these groups rather than arguing over which group is larger.

Reference

Merikangas K, et al. (2013) Medication Use in US Youth With Mental Disorders. JAMA Pediatrics 167(2):141-148.