The Altar-native Perspective of Afto-Atlantic Religions

Background Information

The concept of aṣe is ever present in the construction and use of Yoruba altars. In order to understand Yoruba art, you have to understand aṣe. Everything has aṣe, it is power, authority, energy, and it is vital. All objects on Yoruba altars have aṣe. Yoruba altars are constructed differently based on which oriṣa they are for, and who makes the altar. The consistency in objects that you may find on Yoruba altars would be the symbols and colors of the god that they are for. Blue and white would be on an altar for Yemoja, as well as symbols of the ocean and twin figures. Yemoja is the mother of the waters, she is associated with salt water, motherhood, children, the full moon, pregnancy, and women. She gave birth to fourteen other oriṣas, leading her to be the protector of children. Altars for her will also sometimes contain symbols of her son, Ṣango, the god of thunder. Yoruba altars can be general or they can be personal, and more often than not they  are personal. There may be objects on an altar that are not traditional or not found on most altars for the oriṣa the altar is for. The oriṣas are not strangers to change, they welcome it, and so if something on an altar is not traditional, the oriṣas have no problem with it.

are personal. There may be objects on an altar that are not traditional or not found on most altars for the oriṣa the altar is for. The oriṣas are not strangers to change, they welcome it, and so if something on an altar is not traditional, the oriṣas have no problem with it.

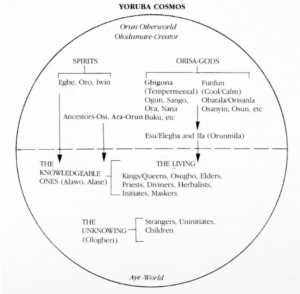

The Yoruba people are a people in southwestern and north-central Nigeria as well as southern and central Benin. During the transatlantic slave trade, many of the slaves that ended up in the Americas and in the Caribbean were Yoruba. The Yoruba religion mixed with Christianity and many oriṣas now have counterparts to Saints. Yemoja’s syncretized counterpart is Our Lady of Regla. Yemonja is linked with the oriṣa Olokun, who represents the bottom of the sea. According to Yoruba myths, Yemonja originated in the Oke Ogun area in Nigeria. She is often portrayed as the wife of different make oriṣas like Obatala and Orisha Oko. Oriṣas are sorted into two groups based on temperament. They are generally organized in the categories of “hot” and “cool/calm.” Yemoja is on the cool/calm side, whereas oriṣas like Ṣango or Ogun are “hot.” According to Yoruba cosmology Yemoja is said to be the mother of Ogun, Ṣango, Oya, Oṣun, Oba, Orisha Oko, Osoosi, and Babalauiye, but she was closest with her son, Ṣango.

The altar for Yemoja in the Fleming Museum is specifically for Yemoja of the One Cowrie Necklace. This Yemoja is specific to Professor Lorand Matory, who created this altar with help from a Yoruba priestess. This Yemoja’s personality reflects Professor Matory’s personality and his personality reflects hers. The altar features many traditional and nontraditional aspects of Yoruba altars.

Some of the nontraditional objects include the photos found on the altar. One of them (1) depicts a priest of Yemoja in Nigeria who commented on Professor Matory’s relationship with his now wife. The photographs represent Professor Matory’s relationship with his Yemoja and his personal history with the people of Yemoja. More traditional objects on the altar are the Ìbeji (3, 22) and the embodiment of Yemoja (25). There are the Ère Ìbejì Ìbẹẹ̀ta, which are triplet statuettes (3) and then there are the Ère Ìbejì, the twin figures (22). It is said that Yemoja took in the Ìbejì and raised them. In Yoruba culture, twins are special and viewed as magical, the Ìbejì represent motherhood and the protection of children on this altar. The embodiment of Yemoja, found in the middle of the altar, shows Yemoja as a mermaid within a large calabash vessel. Yemoja is usually depicted as a double-tailed mermaid due to her association with the river Ogun and with salt water. The river stone (27), is another water symbol to help bring Yemoja’s presence to the altar along with all the other objects.

Objects described in the item catalog are marked with numbers that correspond with the diagram of the altar shown above.

Another somewhat nontraditional object on the altar is a blue candle (11). Traditionally, lanterns are used, however, the lanterns are usually small earthenware dishes with a kind of mouth with a cotton wick sticking out, and when they’re lit they create a lot of smoke. The replacement of the lantern with the candle is an example of syncretism in African diasporic religions. The type of candle found on the altar is a kind of “safety” candle usually found in churches. It is also borrowed from Latin American traditions in religions like Santeria and Candomblé.

Although the altar is primarily for Yemoja, there are objects for Ṣango, Yemoja’s son, found on the altar. In Yoruba mythology, Yemoja was very close with her son Ṣango. He is honored on this altar with pink beads around the blue candle (11), a thunder staff (9), and the Aso Oke beneath all of the objects on the altar (28). Worship of Ṣango is often overlapped with the worship of Yemoja due to the familial connection between them.

It is not just aṣe that makes altars work, it is also the objects on them. Altars for Yemoja will have twin figures, water symbols, symbols of motherhood, and things that she likes, such as gin. Altars may be elaborate but they can also be simple. It is not how big or how extravagant an altar is that makes it work. Yoruba art is never created with the “art for art’s sake” mindset, it is always created with a mindset of “art for life’s sake.” Art is always created with a purpose and that purpose is part of the aṣe that the object has.

Yoruba altars are not usually constructed for museum exhibits. Putting them on display for others generally takes them out of cultural context and into a setting where they can be harder to understand. The altars are used to worship oriṣas and to communicate with them. The art on them is for the oriṣas and shows which oriṣa the altar is for. The objects are usually activated through their arrangement on the altar, ritual, food, water, and light. Once charged with aṣe, Yemoja can be called to and worshipped. The power of Yoruba art and the aṣe in the objects on the altar can bring an oriṣa’s presence to the altar where worshipers can personally connect with them and speak with them.