Walking into the Fleming Museum’s Spirited Things: Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic Exhibit, your eyes are inundated by radiant, intriguing, and esoteric objects of various Afro-Atlantic Religions. There are altars composed to honor various deities, plethoras of shining garments, beaded dolls, colorfully wrapped bottles, gorgeous tapestries with images of deities and mythical beings, gathered to express religious cultures. Families of objects line the walls and floors all telling a story of religious and cultural diversity of Yoruba Religions, Brazilian Candomblé, Santería, Haitian Vodoun, and much more.

To the left of me, in a large glass case surrounded by bottles of rum, cowrie shells, and dolls for wealth and prosperity, lies a strange wand-like object. This object, by reading the tag underneath, is known as the Ibirí Wand of the Goddess Naña. By observation, this object is about 15-20 inches in length, and extends from a straight handle, into two pieces of straw that bend in opposite directions to create an oval shaped looped at the summit of the wand. The ibirí is made of Palha da Costa, or African straw, and is adorned with rows of blue, red, gold and white glass beads. Glass Beads, or any links of beads are said to, within the practice of Candomblé, after being washed in herbal baths or blood offerings, are said to take on the ashe of the deities they are used for, and become a connection or a literal “link” from user or practitioner to the divine. Along with the beads decorating the Ibirí, pearly white cowrie shells, which create an oceanic aspect of the wand, entrancing sections of leather ranging in color, drawing your eyes in all directions around the shape of the wand, are present. Beginning at the base of the handle, my eyes seemed to follow the colors as they changed starting with black, blue, green, yellow, white, and finishing with red. I had never seen an object quite like this, that could catch my eyes and draw them in so many different directions at once, I was eager to discover more about this mesmerizing entity of an object. In this essay, I will provide background information on both the Ibirí and its owner, Naña Buruku. Also, my main question for this essay is how is the Ibirí wand is used, by practitioners of Naña Buruku, within ritualistic practices? Also, I wished to introduce the history of Candomblé, and beliefs within this religion. I also will expand the concept of the spiritual importance that religious objects have. As religious objects can also possess a similar spiritual value as the owner of it, looking past its mundane origin. I will be relating this concept to one of our past readings, “A Sorcerer’s bottle” by Elizabeth McAlister.

To begin, Candomblé, a word who’s meaning “dance in honor of the gods” is “a religion is a mixture of traditional Yoruba, Fon and Bantu beliefs which originated from different regions in Africa. These beliefs were transported within the hearts and souls of slaves during the slave trade. It has also incorporated some aspects of the catholic faith over time. These people, along with their indigenous religious beliefs and practices, were essentially stolen from Africa, and were transported to Brazil. Candomblé, is a hybrid, or a “syncretic” religious mixture of Traditional Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu religious beliefs, all origination from different regions of Africa. Music and Dance are the one of the primarily important aspects of Candomblé, within ceremonies, mainly. Practitioners of Candomblé, believe in one all powerful god, called Oludumaré. He is served by lesser deities called Orishas, whom one of which in Nana Buruku.

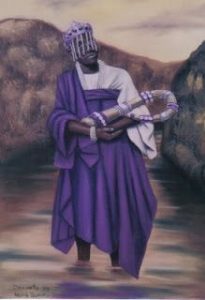

Continuing along the introduction of the orisha, I would like to share a bit of history regarding Naña Buruku. She is again, an orisha, or a lesser deity within the Brazilian religious practice of Candomblé. She is considered the Orisha of Death, Dance, Healing, Disease or Pestilence, and other aspects as well. She is considered a “grandmother” of the Orisha’s and is seen very much as a wise-woman within Candomblé. Two of her children, are Ogun, the orisha of metal or iron, and Obaluaiye, the orisha of smallpox and pestilence. Naña is known amongst practitioners of Candomblé, as a powerful deity for asking for a pregnancy, to terminate a pregnancy, and for various types of healing. She is said to use a similar Ibirí wand to my object in the Fleming Museum, as a broom of sorts, or as a staff to guide her followers and her children to their highest potential, like a grandmother spirit would do. However, just as Naña Buruku uses the Ibirí as a tool for helping her children, grandchildren, and devotees, the Orisha’s tool has also been known as a weapon. With this malicious usage of the Ibirí, or the ileeshin, an alternative Yoruba word for the Ibirí reflects a side of the Grandmother spirit that is rather contradicting and darker. “But if a cruel and horrible person stands before her, she can take the ileeshin, thrust it out horizontally before her and strike its looped tip against the belly of the man” (Thompson 1983, 71). This aspect of the Ibirí suggests an aspect of the Orisha that is just, and seeks to have justice against cruel or unjust people. This tells a sort of duality to Naña Buruku, a balance between nurturing and healing with justice and dealing punishment to those who may deserve it. The Ibirí and Naña both share a very balanced and equal power, dealing with both aspects of the world; that which is cruel and unjust, and that which is healing and has justice. The colors of blue, gold, white and green emphasize the healing and nurturing side of the Orisha, and her desire to watch and guide over her children, grandchildren, and worshippers. After feeling like I needed to understand the Orisha on a more personal and human level, I wished to learn more about the backstory of both the Ibirí and the Orisha, during her human experience.

The Ibirí wand, was said to have been born with Naña Buruku at the beginning of her life on Earth. “Nana has possessed a certain staff from the beginning of her life on earth. She was born with this staff; it was not given to her by anyone… when she was born the staff was embedded in the placenta” (Thompson 1983, 71). This expresses that the history of Naña Buruku and the Ibirí are intertwined and show the dependence both the object and the deity have on each other. The Ibirí, was also said to have been cut from the placenta after birth, and placed into the Earth. The Ibirí was then said to grow as the child grew. “ Then they cut it from the placenta and they put it inside the Earth. But surprisingly, as the infant grew, the staff grew, too” (Thompson 1983, 71). This legend, in a sense emphasizes how Naña Buruku’s áshe, or her divine powers, grew as she did within the Ibirí and also emphasizes the idea within Afro-Atlantic religions that one’s áshe, or divine influence, grows along with them in the world. Moving away from the history of the object itself, into another point of my essay which is how the reflection of Naña Buruku’s ashe, can be seen and acknowledged within the the ibiri, as a vessel of spiritual energy. This connection of energy can be found again, within “A Sorcerer’s Botle” by Elizabeth Mcallister, a past. reading of ours.

Within “A Sorcerer’s Bottle” McAllister discussed how she discovered through a special bottle made for her by a Religious Sorcerer, that were existed so much more beyond the materiality of the object. This reading reminded me of the Ibirí, as the wand seemed to also have a spiritual “mind of it’s own” as well the bottle. The Ibirí was used as a weapon to harm other people at one point. This fact, along with how the wand seemed to grow simultaneously with Nana Buruku, told me that wand had the similar energy as the bottle in the reading. McAllister describes the object as a piece of art, along with a magical entity, as well. “ The bottle was thus commissioned; I thought of it as my first piece of art. Or was it? Right before he gave it to me, the bòkò turned it into a work of magic, a wanga” (McAllister 1995, 305). This quote enforces my idea and additional point of this essay, of the equalized reflection of spiritual value inside an object, to the owner of it. The Ibirí’s power, and its connection to Naña Buruku, showed me the value far beyond the object that sat in front of me in the museum, I related to it’s history and envisioned it’s power and it’s comparison to Naña Buruku. Shifting again from discussing the orisha, to discussing her Ibirí. I’d like to expand more on just what the Ibirí is, it’s ritualistic and spiritual purposes within rituals, etc.

The Ibirí, along with being used by the Orisha herself as a broom, as a staff of guidance, as a weapon, etc. is seen heavily in Candomblé imagery in the crook of Naña Buruku’s arms, as she is swaddling it like a child, again emphasizing her role as a grandmother spirit, a nurturer, and a healer. In one of my research questions, I wanted to discover more about the modern use of the Ibirí within ritualistic practices. This leaded me to discover that worshippers and devotees of Naña Buruku use a form of dancing called Tidalectics, a style of dancing that includes a swaying motion parallel to the action of the oceans waves. Tidalectics, is seldom seen within any other ritual besides one simply worshipping Naña Buruku alone. The Tidalectics style of dancing creates connection to the nature of the Orisha herself, as she has been said to be found near oceans, rivers, and streams. I did not, interestingly, discover much about the use of the object itself during rituals. However, it is still used outside of rituals, as a vessel for the stories of itself and Naña Buruku. After discovering Tidalectics, and it’s connection to the orisha, I began to search for more possible connections to the ocean. I discovered through more research about oceanic connections to the Ibirí and Naña, about Cowrie Shells. These are white, pearly shells, which are naturally used as a representation of water, or of the ocean. The Cowrie shells used to embellish the Ibirí create a further connection between the orisha and to the ocean. The Tidalectics style of dancing also resembled the sweeping motion of a broom, which Naña was said to perform using the Ibirí, to sweep away pestilence and disease. In the practice of Initiation into the practice of Naña Buruku, practitioners will wear long dresses, usually of the color blue or gold, and take corners of their dresses, and sway them back and forth, mimicking the action of sweeping a broom.

After discovering the existence of such an object, my mind has been objected to make many connections between a material object and the nature and personality of an incredibly wise and powerful deity. The Ibirí has allowed me to perceive the nature of an object far beyond just what materials, colors, and embellishments meet the eye. The Ibirí wand also allowed me to discover the existence of a foreign style of dancing I had never encountered before, and can be used to honor a deity who’s uniqueness and respectability is as diverse and eclectic as the object that she has carried since birth. The practice of Candomblé is one that can be perceived as radiant, diverse, and honorable as embodied in Naña Buruku. The Ibirí wand is an object that’s personality and backstory have transcended time itself and continues to live on in antiquity within the walls of the Fleming Museum, waiting their every day to meet all who are lucky to see it, and to teach them about itself and the history of a truly wise grandmother orisha.

Below are photo’s of both the wand itself on the Fleming Museum website on the exhibition and an Illustration of Naña Buruku paired naturally with the Ibirí found via Internet.

Bibliography:

McAlister, Elizabeth. “A Sorcerer’s Bottle .” https://bb.uvm.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-2315560-dt-content-rid-10925763_1/courses/201709-95021/rel298.mcallister.pdf.

Sansi, Roger. “4.” Fetishes and Monuments: Afro-Brazilian Art and Culture in the Twentieth Century, Berghahn, 2010.

Roger Roca-Sansi: Fetishes and Monuments: Afro Brazilian Art and

Griffith, Paul A. “Chapter 4 .” Art and Ritual in the Black Diaspora: Archetypes of Transition, Lexington Books, 2017.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Chapter 1: Black Saints Go Marching in .” Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, Random House, 1983, pp. 68–72.