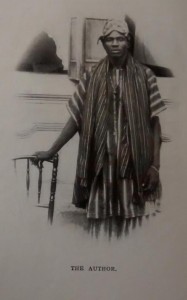

In my last post about Rev. J.J. Ransome-Kuti and the origins of Yoruba gospel music I indicated that there were a number of things that I do not know about his recordings; namely why they were made, how they were distributed and marketed, and who constituted their audiences at the time. I am still continuing to research those questions. However, there is much that is known about Ransome-Kuti and the period of Yoruba church history in which he made his recordings. In today’s post I will write about how we can understand the Ransome-Kuti recordings in relation to both his life history as well to historical developments in Yoruba Christianity.

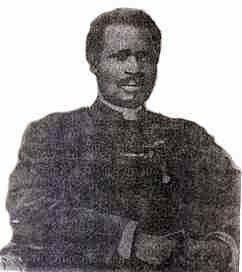

There are a number of published biographies of Ransome-Kuti, though they are mainly available to readers in Nigeria. Of particular interest are two books written by Isaac O. Delano, a Yoruba intellectual from a prominent Christian family in Abeokuta, who wrote a number of books about Yoruba language and culture. Delano’s first book about Ransome-Kuti, The Singing minister of Nigeria, was published in 1942 by the United Society for Christian Literature. The intention of the book, as noted in the Publishers’ Note, was to “stimulate Africans to take an interest in the reading of the great tribes and personalities of their continent.” The second book, Josaiah Ransome-Kuti: The drummer boy who became a canon, is an abridged version of the first, and was published by Oxford University Press in Ibadan, as part of their “Makers of Nigeria” series.

In Delano’s account, Ransome-Kuti is depicted as champion of local Yoruba leadership within mission Christianity. One of the ways Delano does this is through stressing Ransome-Kuti’s devotion both to the Yoruba communities in which he worked as well as to the goals of Christian evangelism and conversion in those communities. Delano describes Ransome-Kuti as “the link between the old and the new civilizations, as well as between the black and white” (51). Thus, even though Ransome-Kuti was a tireless warrior against traditional religion, he recognized the values of Yoruba language, music, and forms of social organization in his ministry. Even though he was a representative of the British colonial administration (according to Delano he was given a mandate by the Egba Government to act on its behalf), he was also a keen voice in support of “native” leadership in the church and at local levels.

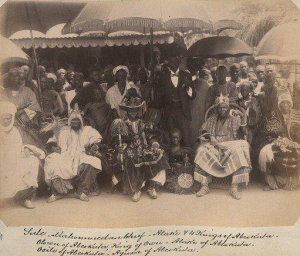

Two examples from his biography make these aspects of Ransome-Kuti’s orientation towards Yoruba Christianity clear. The first concerns his campaign in the town of Ilaro to allow Christians to use umbrellas. The umbrella served as symbol of royal power and for this reason was restricted to the use of the ọba (king) of the town.

Ransome-Kuti’s petition was granted by the palace; however his actions were viewed as threatening to local authority by some members of the community. Ransome-Kuti was attacked with machetes in the night by members of this faction. These actions led to a larger stand-off between the Christians in the community who wanted to take their revenge, the parties connected to the King’s palace who were seen as responsible for the attack, and the British government representatives who sent a battalion of soldiers to the area in anticipation of violence. Ransome-Kuti worked to stave off a large-scale conflict in the community by negotiating between the three sides. The resolution of this event involved the trial of those involved in the attack on Ransome-Kuti in the British court and an easing of tensions between Christians and non-Christians in Ilaro. Ransome-Kuti is identified by Delano as responsible for this; as he writes, “Christianity at Ilaro was built on the blood of Kuti” (35).

At the other end of the spectrum, Ransome-Kuti was also not afraid to challenge the mission leadership and colonial administration in support of the Yoruba communities in which he worked. For example, he challenged the church constitution by baptizing the children of of those whose parents weren’t married in the church and was found guilty by the Episcopal Court for this offense. When his followers in Abeokuta wanted to split from the Diocese over this, he implored them to work to change the church policy from within. Ransome-Kuti’s other clash with church leadership was over whether or not a group of Christian elders who called themselves the “Christian Ogboni” could hold their Thanksgiving service in the church. The Ogboni were a secret society that before colonialism had played an important role in politics and who acted in a judicial capacity in Yoruba communities. The Christian elders at the Ake church in Abeokuta had formed themselves into a similar society, taken titles, and went about settling matters between Christians. For allowing the Christian Ogboni to hold their Thanksgiving service, Ransome-Kuti was charged with “introducing heathenism into the church” (46). Due to the overwhelming support of the local congregation for Ransome-Kuti’s actions, he was let off from this charge with a warning.

It is actions such as these that lead Delano to celebrate Ransome-Kuti for being “a man who stood firmly between the old and the new Egba people at a time when they were passing through difficult and revolutionary changes” ( 63-64). Here, Ransome-Kuti stands as a metaphor for Yoruba modernization.

Such qualities also characterize Delano’s description of Ransome-Kuti’s musical abilities. While Delano writes little about Ransome-Kuti’s musical recordings other than noting that they were made, he does tell us about Ransome-Kuti’s musical endeavors, portraying them as similarly straddling old and new, black and white. Delano writes,

He was first and foremost a craftsman, labouring to build up native music with the same conscience with which a first-class carpenter would build a table. He picked some of the best native airs, polished them up and set them to music. They were more easily followed and understood by the hundreds of converts whom he was to bring into the fold of Christ. [12]

In this way Ransome-Kuti is portrayed as both Christianizing and modernizing (by “polishing up”) Yoruba music at the same time as he translated Christian musical practices to Yoruba communities. Delano also notes the importance of music for galvanizing Yoruba and Christian devotion. Towards the end of the book he describes an enthusiastic crowd listening to Ransome-Kuti preaching in the town market:

Mounted on a petrol box, Kuti would be singing with hand raised, his earnest face illumined but the peace in his soul; his bushy hair waving in the breeze. The people around him would sing lustily. They sang as they felt; they felt as they sang. The same cure, the same key was offered for the unlocking of the mysteries of their hearts. [58-59]

It is in such descriptions that we can better understand why Ransome-Kuti’s songs may have been singled out to be recorded. More importantly, we can see the centrality of musical practice for Yoruba Christian experience—the feelingful aspects of singing that drew converts to the church and made them feel connected to and at ease with the changes that were happening around them at the time.

In my next post I will address some of the musical characteristics of Ransome-Kuti’s songs, in order to better understand how this negotiation between old and new was accomplished musically.