From the Lionsgate website for Orange is the New Black. http://www.lionsgate.com/tv/orangeisthenewblack/

I recently returned from a conference titled “Gender, Media, and Religion” in Boulder, Colorado hosted by the Center for Media, Religion, and Culture at the University of Colorado. Their biennial conferences each address a particular theme within the study of media and religion, and this year’s theme of gender seemed particularly relevant to the Neflix hit show, Orange is the New Black, a show I’m currently writing a chapter about for a textbook. It turned out that at least four other people thought so, too, so I found myself on a panel with three papers addressing that show, each from a different perspective (both of the other papers were co-presented by two scholars). In this blog post, I’ll give a summary of the ideas I presented, and then reflect on the conference as a whole, and the state of the study of religion, media, and gender that it reflects.

In my class introducing the comparative study of religion, I spend some time on the concept of “ontology” and how that fits in with the idea that religions are partly made up of ideas. We focus on the ontological nature of humans in different religious perspectives: do we have souls (Christianity, Islam) or not (Buddhism)? What makes us different from animals? And most relevantly: is a “male” human ontologically different from a “female” human? To me, the show, Orange is the New Black represents in popular culture a change in the answer to this last question. Until recently, most Americans would probably have assumed that yes, men and women are different, ontologically speaking. Sex was presumed to equal gender: if you were born with male genitalia and chromosomes, you were male and the same for female. Television shows notoriously reinforced this gender binary, in shows like Leave it to Beaver or The Honeymooners. As times changed, however, so did Americans’ concepts of gender. Growing up in the ‘70s with transmedia phenomena like Free to Be You and Me meant learning that things we thought were “boy things” or “girl things” didn’t have to be that – they had no ontological or natural connection to gender – and that being a “boy” or “girl” didn’t have to always mean the same thing to everyone.

Fast forward to 2015, and our popular culture now seems divided between those who take for granted that there is no “male” and “female” inherent in a person’s identity, only “human;” and those who see this assumption of a gender spectrum as a threateningly destabilizing force promoted by minority populations bent on undermining society. In internet-speak they are referred to as SJWs (“social justice warriors”). Television shows reflect this division: in the first camp, Orange is the New Black positively portrays a wide variety of gender expressions and sexuality; in the second, other television shows seem to “double down” on “traditional” gender roles. An example of this was convincingly put forward by Rachel Wagner in her paper at the conference. She argued that The Walking Dead draws on regressive New Testament concepts of gender (taken from the later pseudo-Pauline books) that have surfaced largely as a reaction to the perceived social chaos represented by growing empowerment of people of color, women, LGBT, and non-gender binary identified people. It promotes a vision of safety embodied by clearly defined gender roles, associating men with protection and brutality, and women with nurturing and care-taking. When these roles are compromised, the community cannot survive. (An interesting perspective, but this scholar would like to argue that there are more possible ways of reading that show, including as a critique of hypermasculinity.)

In other words, Orange is the New Black celebrates the idea that a person’s gender is not a determinative part of her identity – being a woman or a man is a state of mind, a series of choices and performances, and something that you can change about yourself if you need to.

Yes, you may say to yourself, but what does this have to do with religion? Isn’t this blog supposed to be about religion?

What interested me about this topic, applied to this show, is that the flexible and indeterminate way that gender is incorporated into the show’s narrative is paralleled by the flexible and indeterminate nature of religion on the show. Where television in the past has used religious identity to help create expectations about particular characters (and sometimes subvert those expectations, but usually not), Orange is the New Black allows religion to be a vehicle for telling stories about how people change, not just socially, morally, or in other “coming of age” ways typical of television narratives, but spiritually and in terms of their identity. Religion is a process, or a toolbox for finding ways to cope, or a way to explore new relationships with yourself and others. It is not a way of categorizing “the Jewish character” or “the Catholic character” as it has been traditionally used in television.

For those familiar with the show, especially the third season, the most obvious example of this is the story of Black Cindy. Curious as to how and why a new transfer to the prison is getting better food (broccoli!) in the prison cafeteria, she discovers that the new inmate is using an old trick: claim to be kosher. (Several people of my acquaintance have brought up the question, why kosher, not halal? To which I can only speculate: not enough precedent for humorous situations – no Muslim Woody Allen to riff on?) Soon, a sizable number of inmates from across the racially organized cliques are claiming adherence to Jewish laws of kashrut, and gloating about their broccoli. At first, prison management is hesitant to call the inmates on their fraud, but eventually they do bring in a rabbi to quiz them about their commitment to the Jewish faith. As expected, most of the inmates are as religiously illiterate as a random sampling of Americans can be. (See the Pew Research Center on Religion in Public Life’s 2010 Religious Knowledge Survey, for example.) Cindy, however, decides to push ahead with her identification as Jewish, and learn as much as she can, which she does first by checking out Jewish films from the library, like Yentl and Annie Hall, but then by finding actual Jewish inmates who can coach her on their knowledge of Judaism in practice and doctrine.

Finally, Black Cindy requests another meeting with the Rabbi. She formally asks, in the presence of two other Jews and the Rabbi, to become a Jew. He refuses, and she at first takes this as the standard ritualized refusal that converts are faced with in order to determine that they are committed to the path of Judaism, and not just dabbling. But the Rabbi is unconvinced. Black Cindy is, as her nickname indicates, African American, and as one of the Jewish inmates says, this makes it hard to understand why she would choose to go from being a “hated minority to being a double hated minority.” But she explains that the Christianity she grew up with never made sense to her, and left her feeling judged and alienated for wanting to ask questions. In her new knowledge about Judaism, she feels empowered to search for answers, to struggle with her mistakes and try to fix them, and to approach God as an action or a process. She says, “As far as God’s concerned, it’s your job to keep asking questions, and to keep learning, and keep arguing! It’s like a verb, it’s like, you DO God. And it’s a lot of work.” (You can watch her impassioned conversion on YouTube if you don’t have Netflix.)

But Black Cindy is not the only inmate whose story revolves around religion in the third season of Orange is the New Black. Another important plotline exposes the religious pasts of two inmates who in some ways represent polar opposites, spiritually speaking: Leanne and Norma. Norma is a mute woman probably in her sixties, whose flash-back shows that she joined a new religious movement in her teens, at the height of the “flower power” countercultural movement. Her “guru” is presented by the show as the epitome of the “cult leader:” spouting meaningless “new age” spiritual mumbo jumbo, and surrounding himself with nubile young things so that he can “marry” as many girls as he likes and exploit them sexually, financially, and emotionally. When Norma appears, innocent and wide-eyed, and suffering a debilitating stutter, he tells her that she never has to speak again, which she seems to find empathetic and liberating, but which the audience, I suspect, finds a little creepy. She sticks with him until the bitter end, the only follower left, presumably into the twenty-first century. Ultimately, as one can surmise because after all she is in prison, things do not end well. However, in prison she continues to maintain her silence, which gives her a kind of power and mystery, attracting a group of followers who find in her presence and touch a peace they can’t otherwise experience in the dehumanizing context of the prison.

The amazing thing about this plotline is that it leads to a situation where characters in this dramedy explicitly argue about what religion is, and what it is for, usually a topic only found alluring by students of religion such as myself and my peers. One day, Norma and her followers are meeting in the chapel and another, explicitly Christian, group comes in to claim the space. When the chaplain tells them to leave because they don’t count as a religion, Leanne stands up to explain that they do have “a belief system.” The chaplain has dismissively explained that yes, Christianity was new once, too, but “after hundreds of years of private worship, several great schisms, and thousands of people martyring themselves, it became a focused belief system. With a name.” Leanne responds that they, too, have a faith, but when she explains it, the chaplain reiterates that it is a meditation club, not a religion.

This scene is a lead-in to a series of flashbacks explaining how Leanne ended up in prison. (Previously, Leanne has been a minor, somewhat comic character, largely a foil for the more forceful personality of “Pennsatucky” another meth-head prisoner who provided an evangelical figure for the first two seasons’ plotlines.) Now, we find out that Leanne comes from an Old Order Amish community, and fell into using meth during her experimental time with “the English” and then repented and was accepted back into her family. Unfortunately she had left evidence of her drug dealing, and was persuaded by the police to set up her former drug using friends, which backfired and led to her incarceration as well. Although the depiction of the Amish may not be accurate, it serves to establish at least a symbolic context for Leanne’s relationship to religion. Her background in this religious community shapes her response to Norma, and explains her urge to use her leadership role in the group to define rules and doctrines for them to follow. At the same time, Leanne’s desire to find the sacred in the material world, like the image of Norma in a piece of toast,

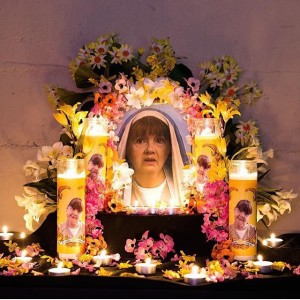

Fan art of Norma found at http://photo.sh/photo-i1111200884985446542_1446767575.html

or the healing sensation of the touch of Norma’s finger on her forehead, speaks perhaps to a longing for a more “mystical” (even Catholic) form of spirituality than is available in the word-centered doctrine and worship of the Amish. So, in one narrative arc, Orange is the New Black gives us 1970s counterculture, Amish Americans, and a New Religion in prison, all of which – as stereotypically as they may be presented — are shown as sincere responses of good people searching for meaning and belonging in spite of their marginal position in American society.

Just as different sexual orientations or gender identifications are sources of tension, comedy, and comfort in the context of the show, religion is also shown as something that can act in ways that are destructive and constructive, creating divisions and connections, and reflecting how Americans, in the words of sociologist Robert Wuthnow, have shifted their religious attention from “dwelling” to “seeking” – looking for new combinations and new homes in religious settings that we are transforming as we adopt them.

If you watch the third season of Orange is the New Black, you will also notice an almost constant stream of religious improvisation, from the first episode, where Pennsatucky creates a memorial to all her many aborted “babies,” to the funeral held by two characters for all the books that must be burned due to a bedbug infestation.

The final, celebratory scene of the season also takes on a spiritual ethos, as the show’s writers and producers use all the tools of lighting, music, slow motion, camera angles, and close-ups to evoke a moment outside of time and space, where reconciliation, joy, rebirth, and even liberation may be possible to these inmates, if only for a few, stolen moments.

Finally, my very brief thoughts on the conference in Boulder. The papers I heard there, and the many informal conversations, were inspiring and thought provoking. It seemed clear in many instances that a fourth variable was implied or necessary in this matrix of religion, gender, and media, and that was race. As a scholar, however, it is a challenge to handle the intersectionality of these cultural categories, after being trained so long and intensively in just one or two. The field of religious studies has long understood itself to be interdisciplinary on the one hand and distinctively located on the other, struggling with the need to learn the methods and theories of other disciplines while maintaining a distinctive niche of our own. This conference was one of those spaces where “experts” from across the disciplines actually did come face to face and exchange ideas, inspiration, and perspectives, and I am convinced that the field is stronger for it.

Evan Thompson’s

Evan Thompson’s

evance of work by UVM faculty, students, and alumni. It featured a number of Religion Department faculty!

evance of work by UVM faculty, students, and alumni. It featured a number of Religion Department faculty!