What’s in a quote? Writers, conversationalists, or jazz improvisers can incorporate quotes from well-known sources into their writing, speaking, or playing for many different reasons, and with many different levels of success. In the lyrics to his song ‘Brush Up Your Shakespeare’, Cole Porter suggests that quoting famous authors can impress a potential romantic partner: ‘brush up your Shakespeare/start quoting him now/brush up your Shakespeare/and the women you will wow’. The song originally appeared in the musical ‘Kiss Me Kate’, where it is improvised by gangsters who are trying to kill time while they are accidentally caught onstage during a performance of a Shakespeare play. The gangsters mispronounce multiple names of Shakepearean characters, sounding like they are in a desperate bid to impress. It appears that the gangsters’ knowledge of Shakespeare is limited to a long list of play titles, which they rhyme with all manner of bawdy and ribald thoughts on dating, which in turn display zero knowledge about the contexts of the plays. As the video from the 2001 Broadway production of Kiss Me Kate demonstrates, when the song is combined with authentic New York City accents and pinstripe suits, the results can be hilarious.

More substantive uses of quotation can be heard in Amiri Baraka’s in his poem ‘I Love Music’, which begins with three sentences quoted from John Coltrane, and Wardell Gray’s tenor saxophone solo on ‘Twisted’, which begins with a musical quote from Charlie Parker (as I explain in my post The Magic Number.) In both Baraka’s poem and Gray’s solo, the opening quote allows the new material that follows it to be heard as an answer to or meditation on the quote, and elements of the opening quote are incorporated into the new material that follows the quote. Yet another substantive way of using quotations can be seen in Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s ‘How Long, Not Long’ speech, in which King powerfully incorporates quotes throughout, including from the songs ‘Lift Ev’ry Voice And Sing’, ‘Joshua Fit The Battle of Jericho’ and ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’ and from texts including Psalm 13 from Hebrew Scripture (from which King draws the repetition of ‘How Long?’) and a sermon excerpt by the nineteenth-century American Unitarian preacher Theodore Parker (King’s phrase ‘the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice’ is King’s inspired amalgamation of a number of Parker’s phrases.) King’s speech is best understood through consulting both its written and spoken forms.

Bud Powell is repeatedly described as a pianist and composer who has been influential on all generations of jazz players. A recent example of this view is the YouTube video Bud Powell: The Pianist Who Influenced A Generation by the guitar teacher and musical commentator Rick Beato. Powell has been credited with innovations including the ‘shell chord’ style of left hand accompaniment which can also be heard in the playing of his close friends Thelonious Monk and Elmo Hope. His compositions were recorded by his contemporaries (particularly Miles Davis – see below) and have been periodically rediscovered by jazz players of later generations. A number of jazz players have devoted entire albums to Powell’s music, including trumpeter Herb Robertson’s Shades of Bud Powell from 1988, in which Robertson arranged Powell’s tunes for a brass ensemble, Chick Corea’s Remembering Bud Powell from 1997, Ethan Iverson’s Bud Powell In The 21st Century from 2018, and guitarist Pasquale Grasso’s Solo Bud from 2020. What seems to have been less noted is the influence of the melodic vocabulary in Powell’s compositions and improvised solos on the composing and improvising of other jazz players. As I will show, very soon after Powell’s recorded solos and compositions were released, the influence of his melodic vocabulary began to show in the recordings of his contemporaries in the form of quotes from of his melodic phrases that they interpolated into their own improvised and composed lines, and this kind of influence has continued to the present.

For me, finding patterns from Bud Powell’s melodic language recurring in his own playing and that of other players can carry the kind of thrill that I imagine might be felt by cryptanalysts cracking a code. Oxford Languages defines a cryptanalyst as ‘an expert in deciphering coded messages without prior knowledge of the key’. Many recent popular novels and films portray fictional stories or dramatizations of true stories about people who break the code in messages sent by one arm of an evil regime to another. One of the best of these is The Imitation Game, which portrays the brilliant mathematician Alan Turing’s leadership of a team of cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park, a code-breaking facility of the English military near London working to decode messages sent by the German military using the Enigma machine. A turning point in the plot of the film is a scene in which Turing learns that a female cryptanalyst has discovered a repeating pattern in the messages she has been analyzing. While this may well be a fictionalized simplification of a much more complex process, Benedict Cumberbatch’s portrayal of Turing’s heightened state as he looks for more repeating patterns resonates with my own experience of finding patterns in solos by Bud Powell and in solos where other players emulate, assimilate and innovate on his phrases.

An important difference in Turing’s experience as portrayed by Cumberbatch and my own experience is that while Turing decoded messages sent by an evil regime and thus contributes to the end of a grisly and tragic world war, I have found repeated and melodically strong patterns that are like ‘messages’ sent to future listeners and players from a genius who had a famously troubled but ultimately triumphant musical career. The delayed but wide-ranging success of Powell’s career can be seen in how his ‘messages’ have been ‘received’ by both his contemporaries and successive generations, who embedded Powell’s patterns in their solos, and thus ‘relayed’ to new listeners. Powell’s patterns, in both his own solos and those by other players who quote him, are not really ‘encoded’ as the patterns that Turing encountered were. If they have any subtext for those who recognize them, it is simply a reminder that Powell had one of the great melodic vocabularies of any composer or improviser, worthy of revisiting and reimagining many times.

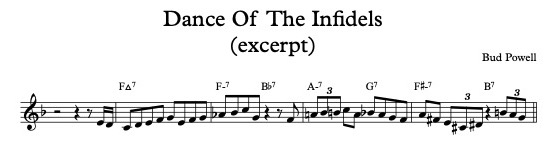

In this sense Powell’s influence on the jazz melodic language has been like that of Shakespeare on spoken and written English in generations following his own. A list on Merriam-Webster.com of Shakespeare phrases in common use has a title – ’10 Phrases From Shakespeare’ – and a selection of stock photos that suggests the effort of a pre-internet brand stretching to follow internet trends. However, it also helpfully cites both the plays in which the phrases appeared and modern contexts in which the phrases have been used. Within this list of phrases, there are three plays (The Tempest, The Merchant of Venice and Hamlet) that contribute two phrases each to the list. As I have listened for Bud Powell patterns in the improvising of other jazz players, particularly pianists, I have noticed a similar pattern of particular Powell solos and compositions recurring in quotations by multiple players. In this post I will be discussing allusions by other improvisers to Powell’s compositions Wail, Dance of The Infidels and Celia and his solos on Celia and Buzzy. (I have also collected a number of solos that quote Powell’s solos on Un Poco Loco and Tempus Fugit, but will save those for a future post.) If nothing else, I think these quotations by other players suggest that these compositions and solos are good places to start for listeners and musicians looking for a way into Powell’s work. I hope that this collection of Powell allusions might have the beginnings of useful answers to the question of what the value is in studying a jazz player’s melodic language in more granular detail rather than simply looking at the totality of harmony and melody in a given composition.

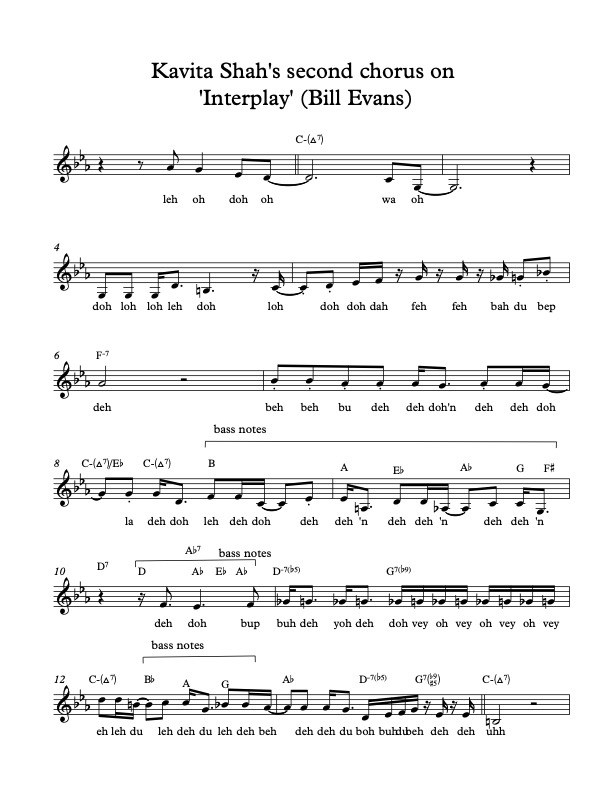

While musicians who effectively quote Bud Powell tunes or solos in their own tunes or solos are creating an overall melodic experience that any listener can enjoy, they are also displaying a level of fandom in which a superfan uses an allusion to a beloved but obscure text or language as a secret signal to other fans. A concentrated example of how Charlie Parker fans engaged in the same practice can be heard in tune Then You’ll Be Boppin’ Too by bebop-era vocalist Babs Gonzales, where an 18-year-old Sonny Rollins quotes the same Parker phrase twice during his solo (the first quote is at :40), and in the solo that follows, a 17-year-old Wynton Kelly finds a different way to quote the same phrase yet again. For me, this is reminiscent of Jim Parsons’ character Sheldon speaking Klingon to a fellow Star Trek fan in The Big Bang theory, or Stephen Colbert speaking Quenya, the Elvish language from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, on late night television. (Colbert makes typically self-depricating humor out of no one in the audience understanding his reference, but he seems to have faith that at least one fellow Tolkien fan was in the TV-viewing audience, and I was.) During his tenure as Colbert’s musical director on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, which sadly ended in August 2022, jazz pianist Jon Batiste laced Colbert’s opening monologues on current events with musical quotes from jazz standards, often comparatively obscure ones by composers including Charlie Parker and Billy Strayhorn, sending a message which could only be decoded by other jazz listeners who knew the tune and realized the relevance of the title to the topic of the Colbert line he was punctuating. In one commentary on Trump where Colbert mentions syphillis, Batiste quotes the Strayhorn tune ‘U.M.M.G.’, which is titled after the acronym for ‘Upper Manhattan Medical Group’.

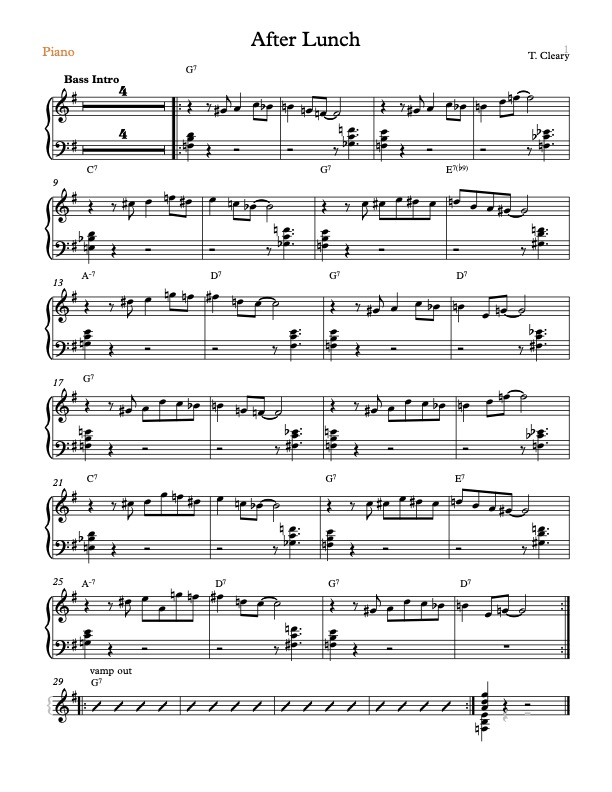

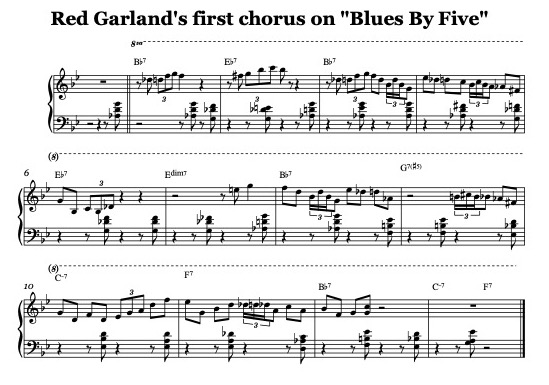

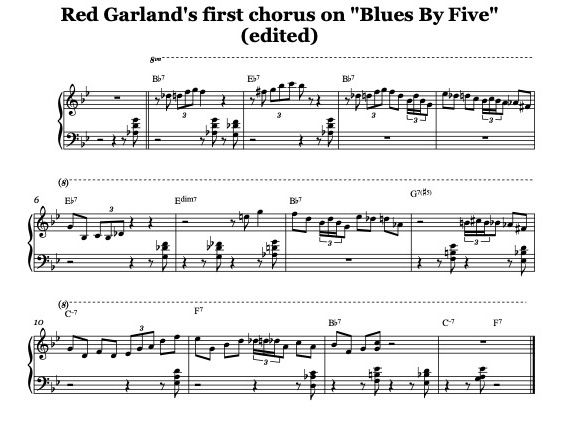

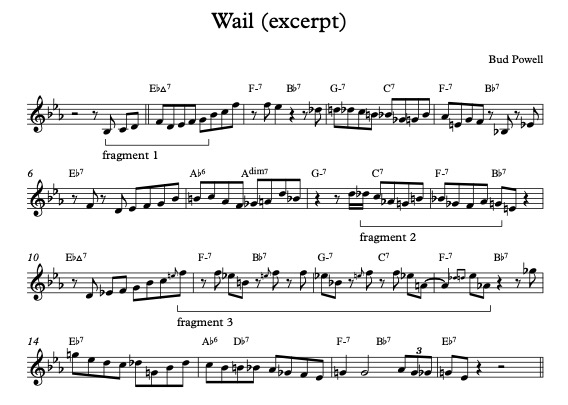

‘Wail‘, first recorded in August of 1946 as ‘Fool’s Fancy’, is one of a number of Powell compositions that use some version of the chord progression from George and Ira Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm’, otherwise known as ‘rhythm changes’. The link in the previous sentence is to Powell’s second version from 1949. Here is a link to a video of me playing the head to ‘Wail’ with my own chord voicings; a single-staff score of the opening to the tune is below. I have bracketed fragments that I have found other soloists and composers borrowing:

In this version one can hear 18-year-old tenor saxophonist and Charlie Parker superfan Sonny Rollins quoting a cornerstone of the Parker vocabulary, ‘Cool Blues’ lick. (I discuss uses of the ‘Cool Blues’ lick in my post Taking The Fifth.) Only a few months earlier in January of that year, Rollins had quoted the lick verbatim on Babs Gonzalez’ recording of Professor Bop, but in his ‘Wail’ solo he makes a more sophisticated use of tit, expanding it by adding new material between Parker’s opening and closing gestures. Quotation of the melody to ‘Wail’ began as early as a Miles Davis recording session in August of 1947, less than a year after Powell’s recording of ‘Fool’s Fancy’. In measures 10 and 11 of the melody to his composition ‘Half Nelson’, recorded at the 1947 session, Davis included a phrase that rhythmic and melodically matches the first eight notes of ‘Wail’ (fragment 1 in the chart).

The likelihood that Davis borrowed this phrase consciously or subconsciously from Powell’s tune is supported by a number of historical facts. First, the original recording of ‘Wail’ under the title ‘Fool’s Fancy’ featured Kenny Dorham on trumpet, a contemporary of Davis’ for whom he had deep respect that sometimes manifested as competitiveness. In ‘Miles: The Autobiography’, Davis (through his co-writer Quincy Troupe) says that ‘ I liked [Dorham’s] tone and voice. And he was really creative, imaginative, an artist on that horn. He never got all the credit he deserved’. Davis’s regard for Dorham and his competitive attitude toward him could easily have led Davis to seek out records on which Dorham was a featured sideman and particularly to learn a challenging ‘head’ or melody statement like ‘Fool’s Fancy’/’Wail’, which (like Davis’ ‘Donna Lee’) was a set of melodic hurdles created by a composer/virtuoso for their highly skilled bandmates.

There is also evidence in Davis’ recording career, both during and after the ‘Half Nelson’ session, that he admired Powell as a composer. This evidence was mostly disguised by Davis and the record companies who, as Lewis Porter has shown, intervened for their own benefit and assigned composer credits to him for tunes he recorded by other writers. Davis’ composition ‘Sippin’ At Bells’, recorded on the same session as ‘Half Nelson’, uses the uniquely altered twelve bar blues progression from Powell’s ‘Dance of The Infidels’, recorded after ‘Sippin’ At Bells’ in 1949 but likely heard or even learned by Davis before then (Powell biographer Peter Pullman mentions that Powell was teaching it to Sonny Rollins and Jackie McLean well before the recording.) In 1948, on his iconic album ‘Birth of the Cool’, Davis also recorded an altered version of Powell’s ‘Hallucinations’, which Davis retitled ‘Budo’ and added his name in the composer credits, and in 1953 he recorded Powell’s composition ‘Tempus Fugit’ under its original title (but with a significantly altered bridge).

The tune ‘Milestones’ (sometimes called ‘Old Milestones’ to distinguish it from a similarly named Davis tune), recorded by Davis on the same session as ‘Half Nelson’, has been credited at various times to Charlie Parker or Miles Davis but is now credited by a number of recent sources to pianist John Lewis. ‘Milestones’ opens with an altered version of the ‘Wail’ opening motive (fragment 1) where the last note is lowered by a half step. This motive begins first on middle C and is then transposed up a minor third to start on Eb.

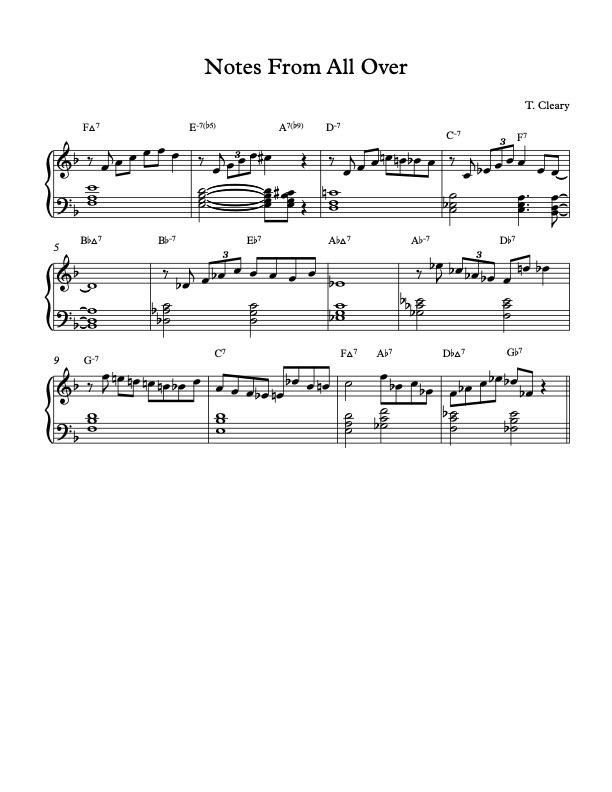

Pianist Sonny Clark was seven years younger than Powell and had an improvisational vocabulary that shows him to be a disciple of Powell’s playing. Clark’s piano solo on his composition ‘Cool Struttin’, shown fairly accurately in this transcription, uses a lick similar to the opening of ‘Wail’ starting on the fourth note of measure 7 (where he alters the middle of the phrase) and on the sixth note of measure 15 (where he plays the first five notes of ‘Wail’ without alteration). The way the lick at measure 7 continues to A4 and C5 and the lick at m. 15 continues to A4 is also evocative of the opening of ‘Wail’. Nine notes in the middle of a phrase at measures 17 and 18 of this solo also match the first nine notes of Powell’s ‘Dance of the Infidels’. (Please note that I mean the first nine notes starting from the first full bar of the melody.) Here is a link to a video of me playing ‘Dance Of The Infidels‘ (along with the intro- note that the melody doesn’t begin until the ninth bar in the video, or :11), and here is a score for the opening of the tune:

The ‘Infidels’ pattern is also prominently featured in the melody of Clark’s composition Junka. The link in the last sentence is to a version with trumpet and tenor saxophone from 1959. In the piano trio version of the tune recorded a year later, Clark cleverly disguises the ‘Infidels’ quote by first removing the second note of the phrase, then adding the missing note back in but preceding the phrase with additional melodic motion.

A chromatic passage in the first two bars of the bridge to Jimmy Rowles’ ‘The Peacocks’, in which minor 3rds descend by half steps through a zig-zag pattern, matches a passage in m. 7-8 of ‘Wail’ (fragment 2 in the chart above) in which major thirds descend by half steps through the same pattern. (The first link in the last sentence is to the version of ‘The Peacocks’ by vocalist Norma Winstone who wrote the lyrics to the tune; in this version the minor-third pattern is clearer than instrumental versions where it is more ornamented.) In the interviews I have read, Rowles does not explicitly cite Powell as one of his influences, but he did perform with Charlie Parker and listed Powell-influenced players like Wynton Kelly as among his ‘favorites’, so it follows that he would have been aware of Powell and might even have learned some of his tunes or some of his licks.

The passage in m. 9-11 of ‘Wail’, in which a chromatic descent from B4 to Ab4 is interspersed with high flourishes between C5 and F5, has had perhaps the longest life of any lick from the tune. Versions of it appear in Horace Silver’s 1955 piano solo on ‘Doodlin’, alto saxophonist Jackie McLean’s composition Bird Lives from the 1988 album Dynasty, and the head out of ‘Sambale’ from pianist Yuri Storione’s 2021 album ‘This Time The Dream’s On Us’. All three of these musicians tend to wear their Bud Powell influence on their sleeve. Silver told interviewer Len Lyons that he ‘used to play a lot of Bud Powell solos off the record’. In a New York Times article about Powell’s 1964 return to Birdland, Silver is quoted as saying: ‘Bud is one of the great sources. He says more in five measures than most players say in five minutes’, indicating that Silver listened in granular detail of Powell’s melodic lines. McLean was one of Powell’s students along with Sonny Rollins. In ‘Wail: The Life of Bud Powell’, Peter Pullman quotes the following conversation between a young McLean and Sonny Rollins when both were between lessons with Powell: ‘Rollins…asked, ‘Hey, I wanna ask you a question. Who’s the baddest, Bud or Bird?’ [McLean replied:] ‘Get outta here, man. What do you mean, who’s the baddest?’ [Rollins:] ‘I know you’re gonna say ‘Bird’.’ {McLean:] ‘Well, yeah.’ And Rollins admonished him: ‘You’d better think about that, and you’d better listen…I’ll see you later.’ Storione’s album ‘This Time The Dream’s On Us’ includes a number of other quotes of Powell licks as well as a tune entitled ‘Viva Bud Powell!’

The melody from the A section of Powell’s tune ‘Celia’, originally recorded between January and February of 1949, is quoted in a solo by pianist Anthony Wonsey on the version of Frank Foster’s ‘Cidade Alta’ from trumpeter Kenyatta Beasley’s 2019 album ‘Frank Foster Songbook’. On his original version of ‘Celia’, Powell begins the break that opens his solo with a 9-note lick that Chick Corea later used repeatedly in his composition ‘Bud Powell’ from the ‘Remembering Bud Powell’ album. (The link to the break will take you to a video where the score to ‘Celia’ is linked to the playback of Powell’s version, and link to the 9-note lick will take you to a keyboard video of the head and solo of ‘Celia’). Before it appeared in the ‘Celia’ solo, Powell used this lick in his solo on the J.J. Johnson rhythm changes ‘Jay Bird’, recorded in June of 1946 (just a few months before ‘Fool’s Fancy’). This phrase is immediately preceded by what might be called a ‘coming attraction’ quote of the melody of Fool’s Fancy/Wail, which he would record for the first time only two months later. The opening of Powell’s ‘Jay Bird’ solo, which is itself an innovative quote of a lick played by J.J. Johnson in the immediately preceding solo, is also quoted in Horace Silver’s solo on his tune ‘Knowledge Box’ from his trio album for Blue Note, recorded in 1952.

In addition to being quoted in the Sonny Clark solo and tune mentioned above, Dance of the Infidels’, recorded by Powell in August of 1949 , also appears in two solos by Horace Silver. The first is in his solo on the recording of his tune ‘Horoscope’ from the aforementioned trio album (an early version before the title was changed to ‘Horacescope’). Silver plays two ‘Infidels’ quotes here back-to-back, the first time altering the original end of the phrase, the second time considerably altering the arc of the phrase. The second solo where he quotes ‘Infidels’ is on ‘Silver’s Serenade’ from the album of the same name from 1963. I discuss this quote in my blog post Conversation Pieces Part Two.

A smaller fragment of the ‘Dance Of The Infidels’ opening (in the melodic minor scale, steps 2-7-1-2-3) can be heard in the third measure of the bridge of ‘Celia’, in measures 1 and 5 of Charles Mingus’s Self Portrait In Three Colors and measure 5 of Mary Lou Williams’s New Blues, meant to represent the bebop era, from her 1978 album The History Of jazz. Mingus is the bass player on a live recording of Charlie Parker performing Dance Of The Infidels with Bud Powell (perhaps the only recording of Parker playing a Powell composition) and Mary Lou Williams was closely associated with Powell over a number of years as a female member of what I call the ‘Three Musketeers Collective’ (centered around Powell, Monk and Elmo Hope) and which I describe in my post Musical Neighbors. While we know Mingus heard ‘Dance Of The Infidels’, it is also likely WIlliams heard it and ‘Celia’.

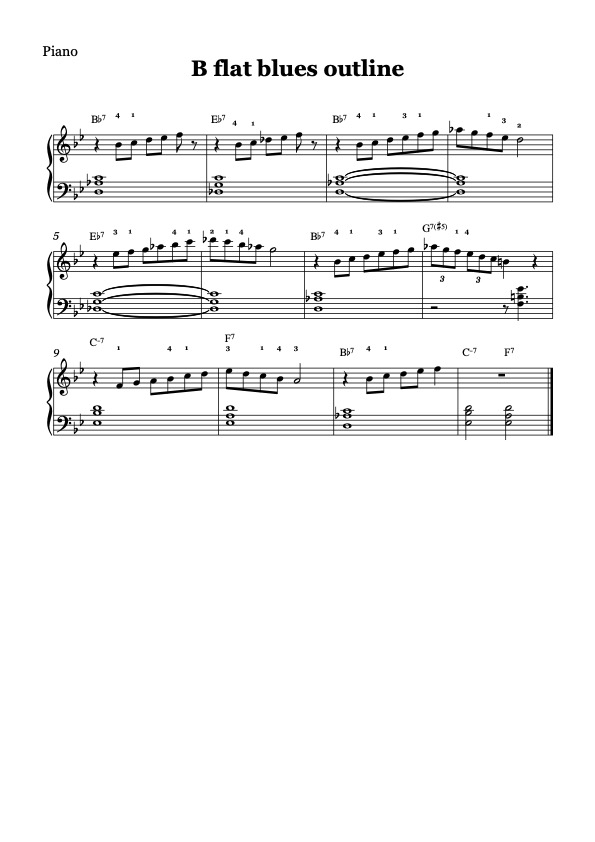

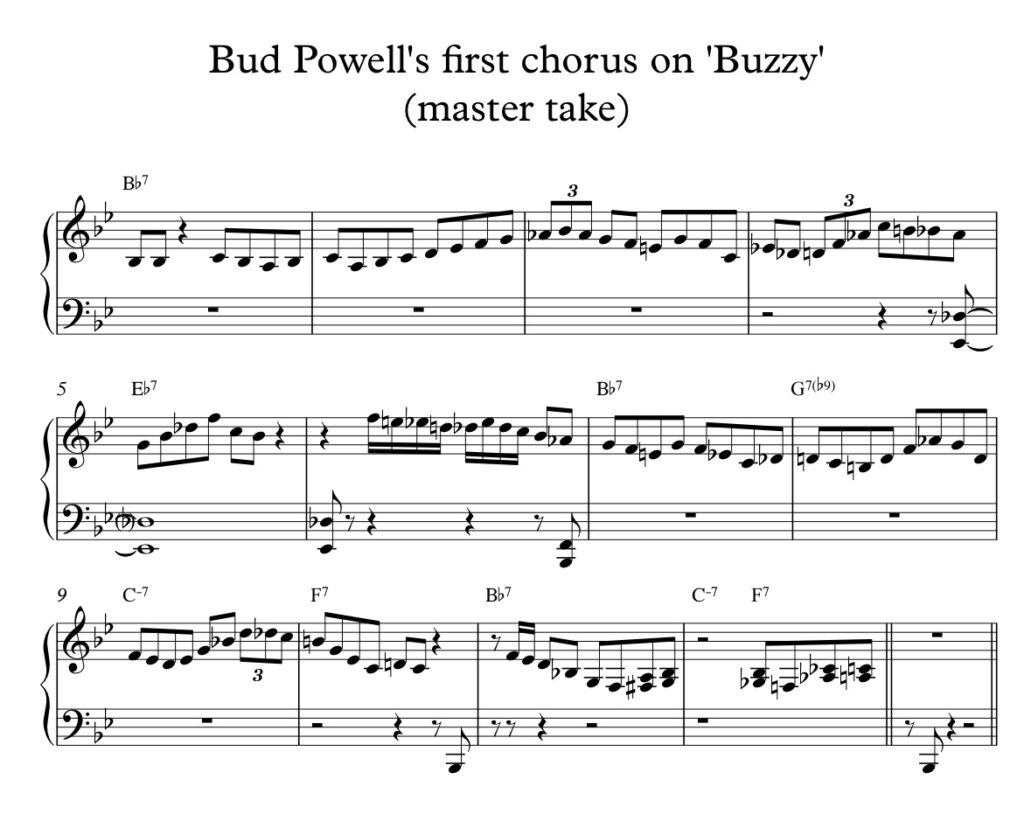

Powell’s solo on the Charlie Parker blues Buzzy, from his only studio session with Parker in 1947, is a remarkable feat of grace and responsiveness which I discuss in my post on Bud Powell and Wynton Kelly. Here is my transcription of the first chorus of the solo, which can be found in the post on Powell and Kelly:

Here is a link to a video of me playing the first chorus of the solo. This solo is quoted in two places during Al Haig’s piano solo on the original Wardell Gray recording of Twisted from 1949, as well as during his comping on the bass solo. One of the licks from the ‘Buzzy’ solo is alluded to by Sonny Clark in his solo on his tune Blues Mambo from 1960 with a version that is both condensed and ornamented. I encourage you to leave a comment in the comment section if you can find the timing where these quotes occur in the Haig and Clark solos. In 1986, Gil Evans used the entire first chorus of Powell’s solo to open his composition ‘Bud and Bird’.

While there is some value in knowing the isolated phrases from Bud Powell’s vocabulary that are quoted by other great jazz players, I find the greater value in identifying these quotations is that it makes me aware of the compositions and solos by Powell to which these players were most drawn. This sends me back to those tunes and solos to re-learn them in more depth and search for other sections I might find useful and inspiring. It also makes me aware in a general way of which corners of Powell’s work may have been less explored. Just as with knowing a commonly quoted phrase from Shakespeare, while one can certainly add the familiar quote to one’s vocabulary, the greater pleasure is in going back to re-experience the original source, hearing the now heightened meaning of the quoted phrase in its original context, and staying tuned for where other less used excerpts may still lie, waiting like old but sturdy tools to be used in the tilling of new garden plots.