The word ‘virus’ is most often associated with negative and harmful microbes, from actual diseases like pneumonia and H1N1 to the fictional virus that kills off most of the Earth’s population in the recent Planet of the Apes movies. The study of ‘good viruses’, however, is also a growing trend in health research, and has moved from identifying individual microbes with positive effects to building a concept of the ‘microbiome’ within each human being, a combination of bacteria in our gut that keeps us healthy. Those who study how ‘good bacteria‘ help to preserve the body might find a metaphor to support their theories by looking at how the vitality of musical traditions and musical communities is often preserved by ‘viral‘ melodic and rhythmic ideas that find their way into multiple songs produced in the same time period. What follow are a few examples of how a particular ‘viral rhythm’, a mutated version of a fundamental rhythm from south of the equator, has had a presence in three different eras of American music.

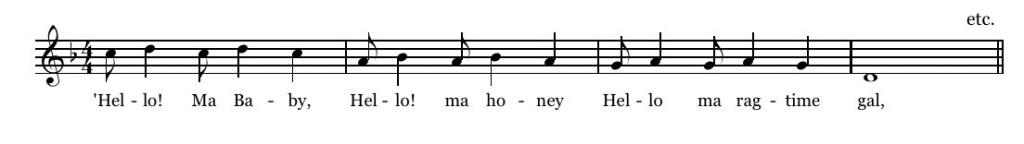

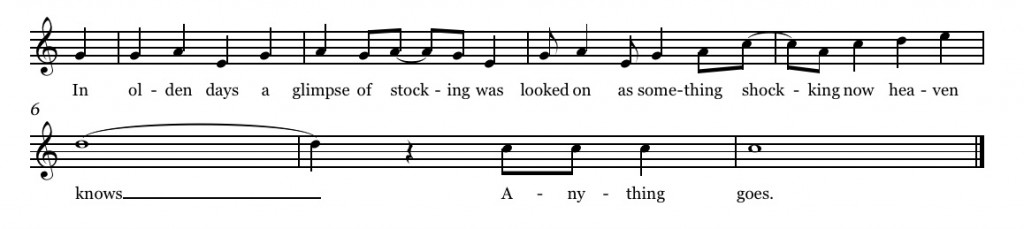

The tune ‘Hello My Baby’ is probably better known today than any other song published in 1899. Whether it is being belted out by a frog in a Warner Brothers cartoon or Phish, it is immediately recognizable from the repeated syncopation that opens the refrain.

The song originally began not with this catchy syncopation but with a long intro verse that can be seen in the original sheet music. A few telltale lyrics in the intro verse (‘some other coon will win her and my game is lost’) show that ‘Hello My Baby’ was originally meant to be an entry in the ‘coon song‘ genre, in which songwriters of the late 19th and early 20th century combined syncopated music with lyrics featuring stereotyped African-American characters. Judging from most versions of the tune currently in circulation, the intro verse and the dialect version of the title (‘Hello! Ma Baby’) – what one might call the harmful part of the virus – have long since been abandoned. I would argue that while the intention to remove prejudicial overtones is certainly one of the motivations for these alterations, there is also a solid musical reason: the intro verse has almost none of the syncopation that makes the refrain so memorable.

That same memorable syncopation also shows up in the lesser-known piano rag ‘Smoky Mokes‘ by Abe Holzman, published the same year. In an early example of how the ‘good bacteria’ in the ‘Hello My Baby’ virus was communicated, Holzman in the opening strain of ‘Smoky Mokes’ appears to cleverly graft the entire melodic rhythm from the refrain of ‘Hello My Baby‘ into his tune while substituting a different sequence of notes:

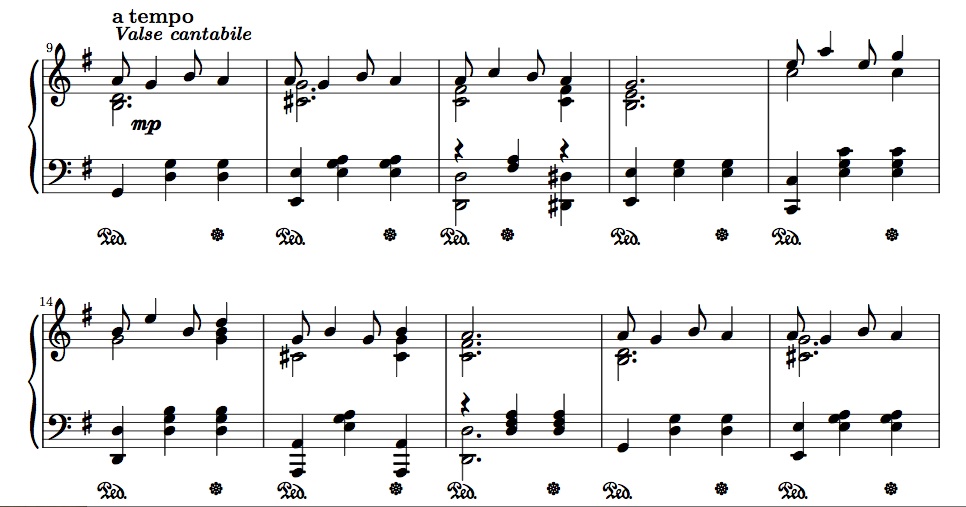

Both tunes can be seen in Denes Agay’s great collection The Joy Of Ragtime, which also features many of the best-known pieces by Scott Joplin (‘Maple Leaf Rag’, ‘The Sycamore’, and of course ‘The Entertainer’, a musical virus if there ever was one: since Marvin Hamlisch’s version on ‘The Sting‘ soundtrack, it has been covered by performers ranging from Milton Berle and the Muppets to Marcus Roberts, who turns in a seriously funky and innovative version on his album ‘The Joy of Joplin’, which is highly recommended for purchase. A fine cover of Roberts’ arrangement by Matt Tabor can be heard on YouTube.) Agay’s collection also includes ‘Pleasant Moments’, one of Joplin’s rare waltzes. To a listener who has ‘Hello My Baby’ deep in their musical subconscious, measures 9 and 10 in ‘Pleasant Moments’ can look and sound like a truncated, three-beat version of the rhythmic figure from that tune and ‘Smoky Mokes’ (and which I will call the ‘truncated habanera’):

Some inspection of the South American tango tradition as represented in piano music, however, shows that both Joplin and ‘Hello My Baby‘ were borrowing this rhythm from a much older source.

The rhythm introduced in the first measure of the refrain in ‘Hello My Baby’, used relentlessly and obsessively throughout the song, and employed more subtly in a truncated version by Joplin, is in fact the habanera rhythm, a typical accompaniment figure in Argentinian tango music with roots in Cuban folk music going back to the 18th century. As the habanera is more of an accompaniment rhythm than a melodic rhythm in tango, it can be seen in its basic form in the left hand of Ernesto Nazareth’s lovely slow ‘Tango Brasiliero’ called ‘Nove de Julho’ (an excerpt follows, but here are links to a complete recording and score):

Nazareth uses a common elaboration of the pattern in his faster-paced tango ‘Garoto’ (recording, score):.

Nazareth, a Brazilian composer, wrote in a number of dance styles typical in his era; the ‘Tango Brasiliero‘ marking in ‘Nove de Julho‘ seems to refer to the slower, gentler pace of this piece, which contrasts with the faster pace of ‘Garoto’, a piece that features an elaboration of the habanera pattern typical in Argentinian tango. After listening to and/or reading through ‘Garoto’, it is interesting to examine another Joplin waltz dated 1905, ‘Bethena’ (heard on the score to the film ‘The Curious Case of Benjamin Button’), in which the truncated habanera hinted at in ‘Pleasant Moments’ can be heard even more clearly and repeatedly:

The mark of Joplin’s greatness as a composer can be seen in his juxtaposition of repeated rhythmic and melodic figures with a constantly evolving harmonic progression; where the repetition in ‘Hello My Baby‘ seems obsessive even within the confines of its sixteen-measure form, Joplin uses repetition of the same idea in ‘Bethena‘ to build undulating waves of tension and release that evolve consistently over a form more than twice as long. (Sheet music for Bethena can be purchased here; Marcus Roberts’ recording of this tune on ‘The Joy of Joplin’ is also highly recommended.)

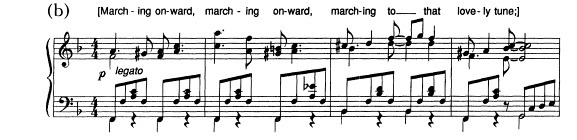

According to Scott Joplin biographer E.A. Berlin, Joplin claimed that composer Irving Berlin plagiarized the opening strain of his first hit song, ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’, from one of Joplin’s pieces, ‘A Real Slow Drag’ from his opera ‘Treemonisha’:

Joplin made the claim after Berlin, who worked for a publisher at the time, reviewed Joplin’s score in 1910, decided against publishing it, but proceeded to publish his own song with its tell-tale phrase the next year:

To me, the similarity of Berlin’s phrase to Joplin’s phrase shows that Berlin, far from being a simple plagiarist, was highly skilled at assimilating other composers’ ideas, and was operating with the same level of sophistication as Joplin when he incorporated the habanera pattern into his waltzes. Once again, however, as with ‘Hello My Baby’, the harmful part of the ‘virus’ – in this case the disputed intro verse – was wisely removed by great communicators such as Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong in their versions of ‘Alexander’. Fitzgerald and Armstrong may not have been aware of Joplin’s dispute with the intro, but they and their arrangers certainly recognized that the intro verse is less musically strong than the refrain with which the composer followed it. (From a compositional standpoint it is interesting to note that although both Howard and Berlin’s creative impetus seems to have come from the instinct to imitate – Howard imitates the ‘coon song’ genre, Berlin imitates Joplin’s score – it was not the most culturally or musically imitative section that produced the strongest music. The most memorable sections of both tunes came after a section mimicking a current trend, and the versions of these songs that have endured are those shorn of their original mimickry. Joplin’s genius in ‘Bethena’ and ‘Pleasant Moments’, on the other hand, was to incorporate a germ of an idea from an external source and make it part of an utterly original, memorable and musically enduring whole.)

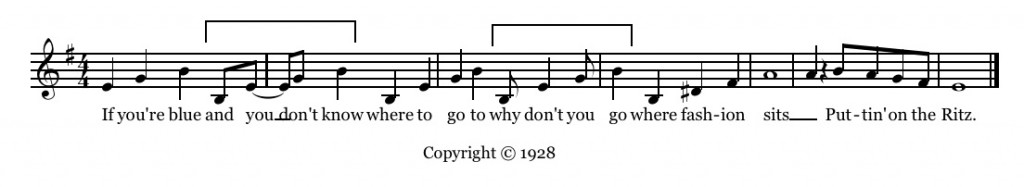

I believe Berlin’s skill at assimilation can also be heard in ‘Puttin’ On The Ritz’, a tune copyrighted in 1928 that uses the truncated habanera rhythm twice in its first four measures:

As the ‘Alexander’s’ story establishes that Berlin was a student of Joplin’s innovations, it seems at least possible that, even though the habanera was everywhere at the time, Berlin’s knowledge of this rhythm may have come from Joplin’s waltz. More evidence that the truncated habanera rhythm was ‘going viral’ in the world of popular song around this time is in Duke Ellington’s 1932 tune ‘It Don’t Mean A Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)’ , which uses the rhythm four times in a row in the second phrase of (as well as many more times in the coda of the tune’s first recorded version):

Cole Porter used the truncated habanera three times in a row in the first phrase of the tune ‘Anything Goes’ (from the 1934 musical of the same name), (as well as five times in its bridge):

(Although I have arranged these examples and the ones that follow in chronological order, my point is not to prove conclusively that any one song directly influenced the other, but rather to illustrate how each tune takes the truncated habanera and uses it in a different way. A number of these tunes are standard literature in the jazz tradition, and their uses of the truncated habanera are among the more sophisticated and technically challenging elements of the melodies for performers. If one can grasp the commonality between these tunes, it can be an aid to mastering one of their complexities.)

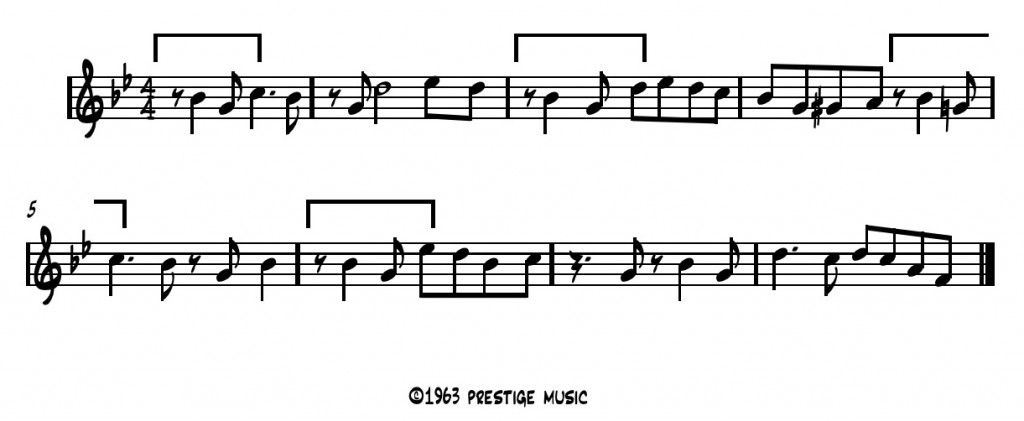

It sounds to me like the truncated habanera also went viral in the bebop era of jazz, as it shows up in an ornamented form the melody of one of Charlie Parker’s best-known compositions, ‘Billie’s Bounce’ (first recorded in 1945). Parker, like Berlin in ‘Puttin’ On The Ritz’, begins the truncated habanera on the fourth beat of his tune’s first measure, but unlike Berlin he repeats the pattern three times, although he replaces the pattern’s first note with a rest on the second and third repetitions.

The same subtractive use of the pattern was also made by Sonny Rollins in his tune ‘Oleo’ (first recorded in 1954 for the Miles Davis album ‘Bags’ Groove’). In the way the tune is most often notated and played, Rollins’ use of the truncated habanera is most noticeable in m. 1, 3, 4 and 6:

On Bill Evans’ version of Oleo (from ‘Everybody Digs Bill Evans’, recorded in 1958) Philly Joe Jones’ three-against-four hi-hat pattern in the second A makes the tune’s first two measures sound like two repetitions in a row of the truncated habanera, filling in the missing first note of the pattern for its first two repetitions, and making the listener hear two three-beat phrases:.

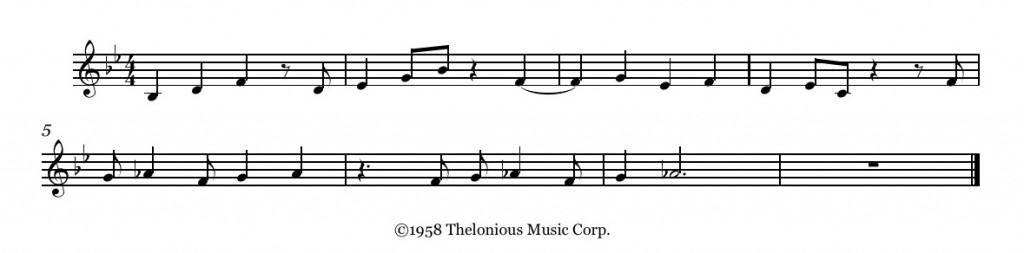

Thelonious Monk, in his tune ‘Rhythm-A-Ning’ (first recorded in 1957), begins with what has often been identified as a four-measure quote from the Mary Lou Williams composition ‘Walkin’ and Swingin’ (see 1:22 of the linked recording by the Vermont All State Jazz Ensemble for the phrase in question.) Monk follows this phrase with a melodic phrase that uses the full four-beat habanera pattern (with an added pickup) in measure 5. This is the pattern we heard in the melody ‘Hello My Baby’ and the left hand of ‘Garoto’. In typical Monk fashion, this second semi-quoted element is then transformed by being stated on a different beat of the measure in bar 6.

(Monk investigates this process further in ‘Straight, No Chaser’, where a rhythmic figure introduced initially on the pickup to beat 1 in measure 1 is then begun on beats 2, 3 and 4 of various measures over course of the first eight measure phrase.)

I have discovered the connections I’m discussing here over years of playing jazz gigs, teaching piano lessons and improvisation classes, and directing pit orchestras, but my awareness of them was reawakened during a great performance I saw earlier this year by Arturo O’Farrill and The Afro-Latin Jazz Orchestra at the Flynn Center. One of the concert’s standout pieces was O’Farrill’s composition ‘On The Corner of Malecon and Bourbon’ from their recent album ‘The Offense of The Drum’. In the YouTube video of this piece, after solos by O’Farrill on piano, Bobby Porcelli on alto sax (who references Cannonball Adderly’s ‘So What’ solo), Jim Seeley on trumpet (who references ‘West End Blues’ and ‘Struttin’ With Some Barbeque’ among other tunes), Jason Marshall on baritone sax (who picks up and develops the ‘Struttin’ lick) and Gregg August on bass, the band settles into a section in which the accompaniment and melody are both strongly reminiscent of the opening strain of Scott Joplin’s ‘Maple Leaf Rag’. In both the YouTube video and the Burlington performance, O’Farrill mentioned in his spoken intro that the piece is about the common roots of jazz and Latin music, but in Burlington he also added a highly instructive piece of stagecraft. In a tone of voice that conveyed believable honesty, O’Farrill claimed that he wasn’t too sure about the ending – a statement which, if he really meant it, would be shocking for someone of O’Farrill’s stature and virtuosity. Although this seemed at first to be a sincere confession, it was actually a shrewd piece of acting that set the audience up for a bit that O’Farrill engages in during an unaccompanied piano solo in the middle of the piece. The band drops out for what seems like a piano cadenza, and O’Farrill first plays in a ragtime piano style with a left hand stride pattern and syncopated melody, but he then slows down as though his mind is stuck on some detail of the music. After an awkward pause, he turns the chart on his music rack upside down and plays an inverted version of the syncopated melody. Here again he slows down and repeats a bar as though analyzing the syncopation, after which he turns the music right side up again and transforms the syncopated melody into one of its close musical relatives: the rhythmic pattern called montuno or guajeo which the piano plays son clave accompaniment style derived from Cuban folk music and common through mambo, salsa and Latin jazz contexts. O’Farrill’s band responds by accompanying the montuno pattern with its typical rhythmic counterpoints in the percussion and bass parts, and the piece concludes in a smoking 2-3 son clave feel.

O’Farrill’s piece brilliantly illustrates that, although videos that ‘go viral‘ on the internet are a fairly recent phenomenon (such as the Pharell Williams tune ‘Happy’, where the original version was quickly followed with remakes by groups from the Miss USA contestants to a grade school class), in the intertwined evolution of tango, ragtime, jazz and popular song, rhythms ‘went viral’ for many decades before the internet with only the ears, eyes and memories of composers to communicate them. Having recently fought off pnuemonia myself, I certainly wouldn’t wish a medical virus on anyone. However, as the word ‘viral’ has taken on a positive meaning in the world of the internet, perhaps someday as studies of medicine and music continue to intertwine, ‘viral’ can take on a positive meaning in the study of music, as a way of explaining the sometimes peculiar and always fascinating ways that musical ideas are leaked and communicated between cultures and eras.

Ian Crane, one of my piano students who is also a student at UVM College of Medicine, wrote an email response to an earlier version of this blog which confirms my sense that the ‘good virus’ metaphor works to illustrate how indirect influence in music can be just as powerful as direct influence. Ian explains it better than I could, so I’ll give him the last word: “I think one way in which viruses work similar to musical ideas is the ‘lysogenic life cycle’. Certain viruses actually travel in between cells and incorporate their genetic code (which is all a virus really is: a traveling piece of DNA or RNA) into the genetic code of a cell. There they lie dormant and are replicated with that cell’s DNA, from that point on effectively changing the genetic code of that cell and all of its progeny…I think music is really similar to this aspect of the viral life cycle in the sense that it can permanently change our musical code, or our set of musical ideas, becoming a part of us.”