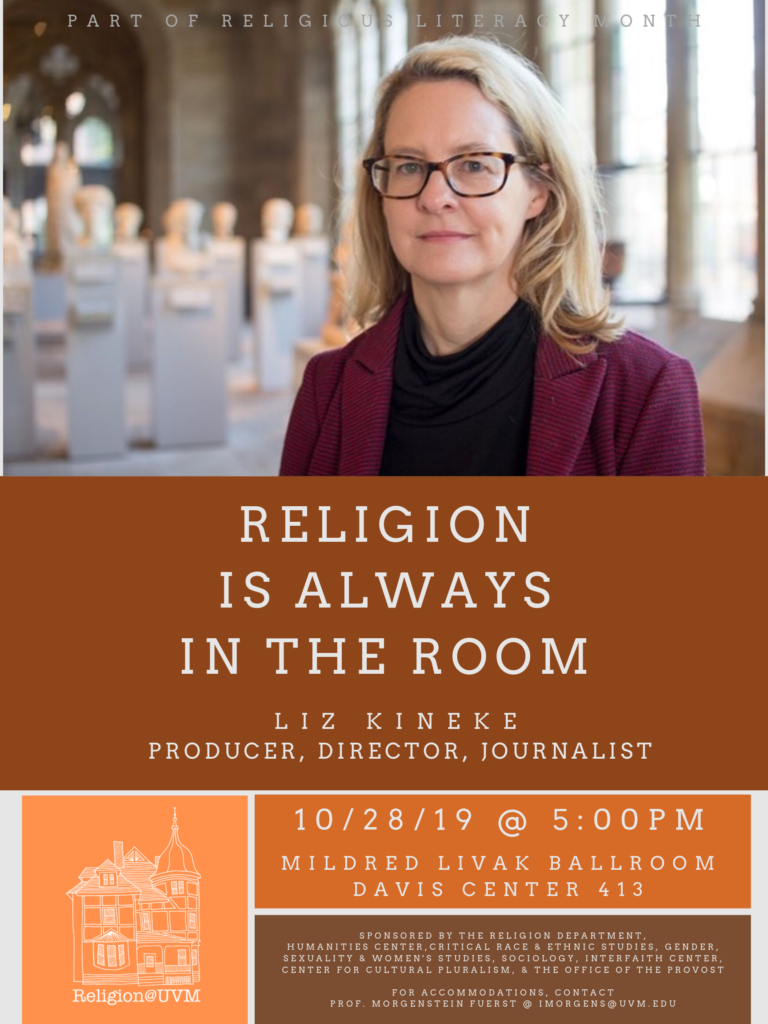

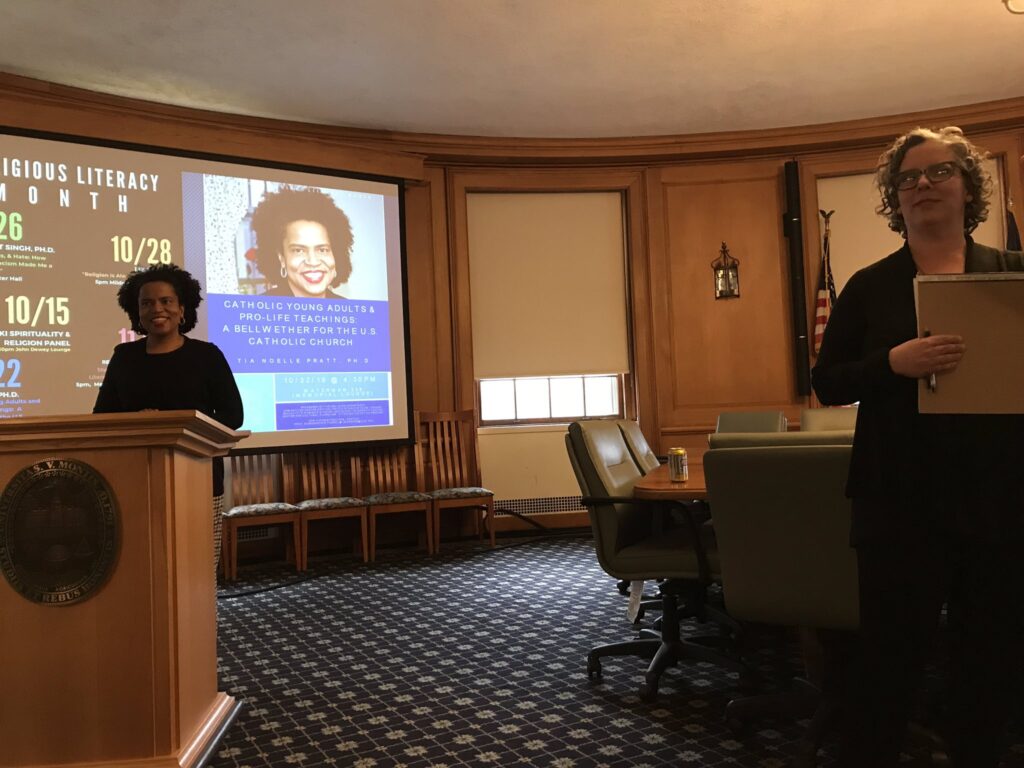

On Monday October 28, Liz Kineke delivered a talk that discussed her overall work in the news and journalism industry with an emphasis on how “Religion is Always in the Room.” During her presentation, she went over her origin story and how she got involved in reporting on religion and what she has learned. She mentioned that she learned that religion is not about what people believe, it is about what they do and how they act, which ties directly into my REL031: Introducing Hinduism class’ overarching theme of analyzing the behaviors of Hindus and understanding how Hindus use and react to their texts.

After going over the start to her career, Kineke got into some of the more prevalent topics in her work, namely religion and politics. Kineke made sure to emphasize that in the case of politics, religion is always in the room, and that it’s impossible to have one without the other. She led with the point that although religion is deeply embedded in our culture, and is our first and most important freedom, our country lacks religious literacy. She said that four years ago religion was a white noise hum, but today it is a blaring siren, linking that fact to the idea that our country’s religious illiteracy results in violence and “micro-aggressions” towards religious minorities and an increase in white supremacy. Kineke’s allusion of the white supremacy linked with Trump’s administration relates directly to our class on Thursday where we discussed the Hindu nationalism that is associated with Ram and the Ramayana. Trump’s political views have led to an uprising in White Nationalism in the country, inspiring the narrative that white Christianity is the religion of this country, and that religious minorities are dangerous, specifically that Muslims are terrorists. In South Asia, many Hindus have used the Ramayana and Ram’s leadership as the “rightful” leader of India to jump to similar conclusions about Muslims, leading to violence and discrimination.

Kineke showed us a piece she did called Faith on the Frontlines about the riots in Charlottesville, Virginia, through the eyes of the clergy. The clergy pointed out that the white nationalist groups gathering in Charlottesville preach ideas that add to the oppression of minority religions in addition to supporting radical right-wing Conservative principles. By narrating the story through the perspectives of religious leaders, Kineke drove home the point that it is impossible to separate religion from politics, and that many of these acts of terrorism are attacks on religious minorities and a violation of our First Amendment rights. The footage she showed of the Charlottesville rally was similar in effect to the pictures we saw in class of mobs tearing down the Babri Masjid with their bare hands and then posing in front of the burning ruins with their hands in fists and large smiles on their faces. The destruction of a mosque in the name of Ram supports Hindu nationalism and claims to draw evidence directly from sacred Hindu texts, specifically Ayodhya being the birthplace of Ram as described in the Ramayana. How can the violation of someone’s sacred space be validated in the name of the most Dharmic man in all of India? How can it be allowed for the president of the United States to inspire acts of white supremacy? To adequately analyze either of these acts of terrorism, an understanding on religious beliefs and prejudices must be understood. “Jai Shri Ram” is just as much a political chant as it is a religious chant, and saluting Hitler or dressing as Klansman is just as much a religious act as it is a political act.

I liked that in her presentation Kineke emphasized the importance of education in the improvement of our country’s religious literacy and how although it may not solve all the problems in our country, it will help educate the public on how their actions can be discriminatory or ignorant. We discuss this a lot in REL031, specifically in the context of how we have to be aware of how white people colonized and invaded India and invalidated a lot of the culture that already existed there and how our point of view effects how we learn about Hinduism. Recently, in the Halloween season, we have been talking about how often Hindu practices and gods get disrespected because people don’t know how offensive it can be to dress up as someone else’s god or hang a poster of a Hindu god up on their wall. The more we learn about Hinduism, the more discrimination and offensive acts we can erase from our daily lives.

Kineke drew my attention to the way in which religion is around us all the time, and the more we know about it, the more prepared we can be to address religious acts of violence and political ignorance.