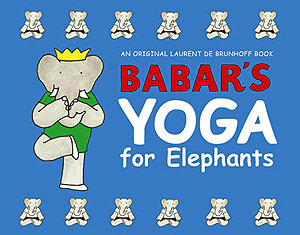

I have an almost-two year old daughter, and she has a legion of Nanas, Pop-Pops, Grandmas, Grandpas, Aunties, Uncles, and general well-wishers who love buying things for her. (This is lovely and appreciated, even if often roundly met with frustration: Please bring less stuff into my house. Please.) In the midst of a now-typical “But, seriously, what does she need?!” conversation, Babar’s Yoga for Elephants, a book in the (revamped, English) Babar series, was suggested as a perfect gift. After all, it’s Babar! And he’s doing yoga!

I have an almost-two year old daughter, and she has a legion of Nanas, Pop-Pops, Grandmas, Grandpas, Aunties, Uncles, and general well-wishers who love buying things for her. (This is lovely and appreciated, even if often roundly met with frustration: Please bring less stuff into my house. Please.) In the midst of a now-typical “But, seriously, what does she need?!” conversation, Babar’s Yoga for Elephants, a book in the (revamped, English) Babar series, was suggested as a perfect gift. After all, it’s Babar! And he’s doing yoga!

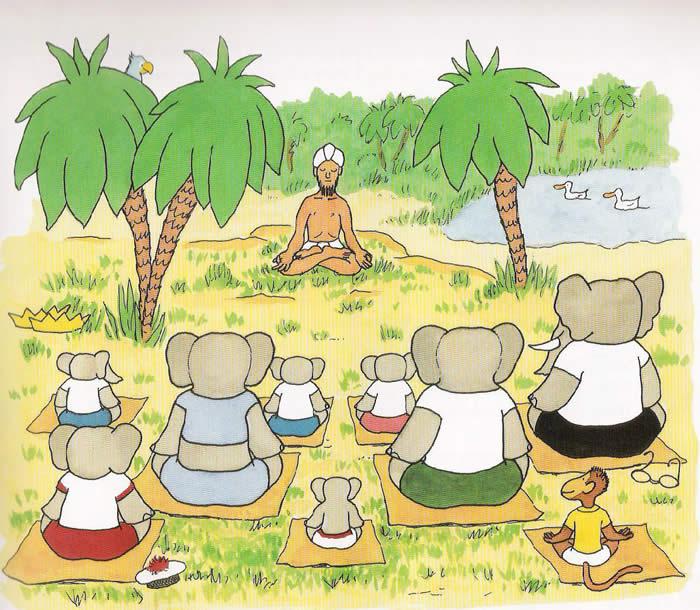

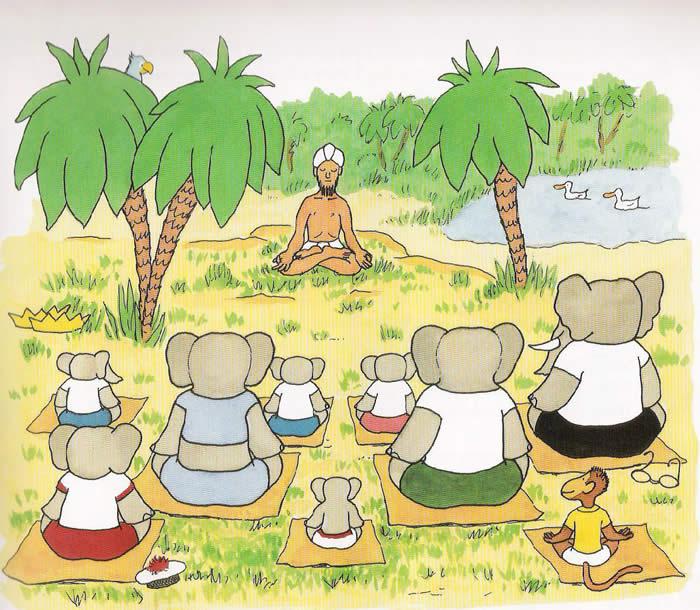

Cue a surprise academic moment. This is Babar, an elephant king who shares his name with Babur, the first Mughal ruler. This is Babar, whom I read about avidly as a child–only to get to college and realize my love of Babar meant I had participated in the orientalist assumptions with which it was written. This is Babar, keeping up with the times and staying fit with yoga. This is Babar, practicing bendy, stretchy, mindful-but-not-religious yoga, at the feet of a stereotypically dressed yogi, fashioned as a dark-skinned, eyes-closed, bearded, bare-chested man in a white turban and wrapped, white bottoms (a dhoti?).

At once, the obvious problems with depicting a generalized South Asian–the man in the image above–are as banal as they are startling. This image is readily critiqued, easily identified, and almost boring in its cliche; yet seeing these problems replicated not in an early-20th century text (when French and English colonialism were in full swing) but rather in a recent book, intended for children, is disconcerting, if not altogether shocking.

Before one even gets to the book, we encounter its dust jacket–which itself serves as fodder for analysis. It reads:

“Well before yoga became fashionable via Sting and Madonna, our friend Babar and all the residents of Celesteville were finding peace and tranquillity through yoga. And now elephants everywhere can join them! … Written by Babar himself, the book explains how yoga was introduced to Celesteville and how he and Celeste keep fit doing yoga on their many travels.” (Replicated here.)

There are multiple truth-claims within this short passage which, in turn, represents the universe in which Babar exists. The first is that Babar is an original practitioner of yoga; his instructional book is thus both authentic and accurate. It ought not to be confused with new iterations of yoga, or newcomers to the practice (like Sting and Madonna), which represent a passing fad and even a disingenuous interest. But while Babar and the residents of Celesteville originally found “peace and tranquility through yoga,” now, in his own words, Babar tells his audience how to “keep fit doing yoga.” What began as a way to find calm, well before it was popular among those living beyond Celesteville, is now a way to keep fit.

A yogi in a cross-legged position doing Machendra asana, British Library: Add.24099, f.14.

This, in some ways, reflects the adoption, adaption, and appropriation of yoga in contemporary, often Euro-American, contexts. What started as a set of disciplines–what yoga literally translates to–in some South Asian religions, for specific participants (usually male, high-caste, and ascetic, as argued by many, for example Sarah Strauss) is now a multi-billion dollar exercise (and perhaps self-help) business. While it’s easy and appropriate to point to the contemporary uses and alterations to yoga, it’s not the whole picture: there is ample evidence that many non-casted, non-Hindu or Buddhist actors have adopted, adapted and appropriated yoga in other historical periods. For example, Muslim Sufis utilized yogic techniques like breathing and meditation, with some even advocating for its adoption into appropriate Islamic praxis (see Ernst here and Kugle there). Yoga, as most other religious ideologies and forms of practice, has been adapted for and by different communities for centuries.

But that doesn’t mean we ought to label Babar practicing yoga as evidence of how normal and normative yoga has become, and move on. There are some for whom this appropriation of yoga is normal, but inappropriate. As schools debate incorporating yoga, mindfulness, and/or meditation into curricula, some Hindus have argued that this misuses their religion, of which yoga is a part; some Christians and atheists, likewise, have argued that allowing these practices in school promotes (a specific) religion, and is inappropriate. All the while, the American Yoga Association claims yoga is not a religion. Debates about what religion is, how it ought to count, and how what counts (or doesn’t) is used are all central to these ongoing conversations, in and outside the public sphere. They also all apply to how we read and see Babar’s Yoga for Elephants. Is Babar practicing religion? Is it spirituality that Babar practices? Is he just participating in a fun, hip exercise program? Or is it a mindful, meditative way to calm down?

If what yoga was, is, and might become is both historically delineated and constantly shifting, how do we read Babar and his instructive yogic text?

Part of my answer to this question lies in thinking about the historical implications and legacies alongside contemporary assumptions and conceptualizations. Babar isn’t just a fun children’s character. He’s an elephant king, developed at the height of colonialism, and, as others have argued, “a tool of colonialist oppression.” In this Babar book, he practices an ancient-but-living Indic form of religiosity (which is, as above, depicted as led by a stereotypically drawn man) for the purpose of “keeping fit.” Beyond contemporary popularity, scientific evidence of its efficacy as a medical treatment for certain issues and people, and the widespread availability of “yoga pants”–in other words, beyond the normative expression of yoga–is a familiar problematic in which someone else’s history, praxis, culture(s), languages, and religions are adopted, adapted, and appropriated, all for our contemporary uses.

My daughter (and I) do participate in yoga. There’s a lovely, local place that offers classes for kids, and my wild, busy toddler loves the space for wiggling, running, and when she slows down long enough, doing an occasional down-dog. Yoga, and our contemporary uses thereof, isn’t inherently a problem. But, with all the complex and overlapping colonialist and orientalist images in Babar’s Yoga for Elephants, she will not get a copy as a gift. Since it seems better suited for my research, I picked up a copy for myself.

I have an almost-two year old daughter, and she has a legion of Nanas, Pop-Pops, Grandmas, Grandpas, Aunties, Uncles, and general well-wishers who love buying things for her. (This is lovely and appreciated, even if often roundly met with frustration: Please bring less stuff into my house. Please.) In the midst of a now-typical “But, seriously, what does she need?!” conversation,

I have an almost-two year old daughter, and she has a legion of Nanas, Pop-Pops, Grandmas, Grandpas, Aunties, Uncles, and general well-wishers who love buying things for her. (This is lovely and appreciated, even if often roundly met with frustration: Please bring less stuff into my house. Please.) In the midst of a now-typical “But, seriously, what does she need?!” conversation,