By Professor Kevin Trainor

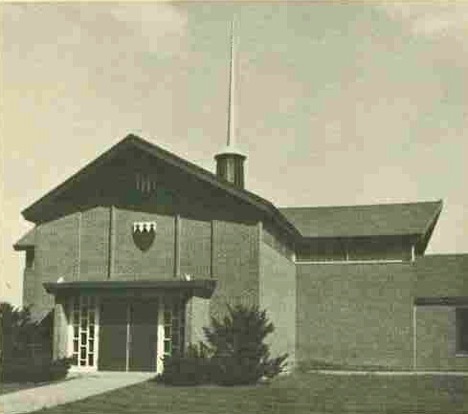

On November 16th, one week after awakening to the shocking result of the presidential election, I attended the formal opening ceremony of UVM’s new Interfaith Center on the Redstone Campus, located in a building with a complicated institutional history. It began fifty-two years ago with another opening ceremony, presided over by Harvey Butterfield, the Episcopal bishop of Vermont, as he dedicated the newly constructed St Anselm’s Chapel. I have been researching that history as part of a broader survey of the teaching and practice of religion at UVM, and in a future blog post I will give a longer overview and analysis of that history, which provides the wider context for understanding the institutional significance of the new Interfaith Center, and of the recent appointment of Laura Engelken as UVM’s first Interfaith Coordinator. Here I will focus on the ceremony itself, and what I think it might mean for UVM’s post-election future.

While I’m not sure that the election results were ever explicitly referenced in the words of the various speakers that afternoon, the fact of Donald Trump’s election, and its apparent validation of his campaign’s embrace of hateful and violent rhetoric, hung like a dark cloud over the proceedings. Like many people with whom I had spoken the previous week, I felt disoriented and anxious about the future. I experienced the election results as a direct assault upon the values and forms of practice to which I, as a member of the UVM community, am committed. It thus seemed fitting to come together with a large group of UVM community members to inaugurate a new university facility whose mission is defined as “creating space for all people to explore and ethically engage the meaning-making systems that sustain their own lives and communities as well as of others” (Interfaith Center Facebook page). The creation of the new Interfaith Coordinator position and the Interfaith Center, which are administered through the university’s Center for Cultural Pluralism, are evidence of UVM’s dramatically expanded institutional engagement with issues of religious and spiritual diversity, now foregrounded as foundational elements in the university’s commitment to diversity, equity, and justice, as encapsulated in UVM’s Our Common Ground statement. This represents a significant shift in policy and practice. At UVM, as at most state-supported public universities, questions arising from community members’ religious identities were for the most part rendered invisible to public discourse, a situation that many community members have found oppressive.

Several members of the UVM community spoke: Laura Engelken (Interfaith Coordinator), Wanda Heading-Grant (Vice President of Human Resources, Diversity and Multicultural Affairs), Tom Sullivan (University President), Annie Stevens (Vice Provost for Student Affairs), and Aya AL-Namee (Senior Admissions Counselor, former Student Government Association President and 2015 UVM alumna), each of whom played an important role in the creation of the Interfaith Center. All the speakers spoke movingly of the personal significance that the new center held for them, but for me the most memorable reflections came from Aya AL-Namee. Identifying herself as a Muslim, she spoke of walking about since the election feeling like “I have a target on my back.” As SGA President in 2015, she played a key role in organizing student support for hiring an interfaith coordinator and for creating a safe place on campus for students to explore and practice their religious and/or spiritual beliefs, which culminated in the passage of an SGA resolution.

St. Anselm’s Chapel from p. 20 of A Goodly Heritage: The Episcopal Church in Vermont. Edited by Kenneth S. Rothwell. Burlington, VT: Cathedral Church of St. Paul, 1973.

But what is a fitting space for religious or spiritual practice on the campus of a public university? This is a complicated question, one that I will explore in greater depth in a future blog entry. But the opening ceremony in which I participated hints at some possible answers. A structure that began its life in the early 1960s as an Episcopal chapel, and then served as the home of the Christ Church Presbyterian community for thirty-five years, took on a new institutional identity at the end of 2013 when the university administration decided not to renew the church’s lease. The Christ Church Presbyterian community vacated the building and found at least a temporary home in the basement of St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral. The space they left behind was emptied of its Christian symbols and furnishings, and during this past summer the structure underwent a basic renovation, which included asbestos abatement and the addition of links to the university infrastructure. A large abstract painting by the artist Peter Heller that covers the north wall of what had been the chapel, which he donated to St. Anselm’s in 1963, was covered over with white muslin. It was within this pleasant but largely empty space that the opening ceremony took place.

Apart from the formal speeches, delivered from a lectern located in the middle of the low raised platform in the center of the main gathering space (which in an earlier incarnation served to define the chancel upon which the altar stood in St. Anselm’s), the opening celebration had the character of an extended and largely unstructured reception during which participants were free to come and go, mingle with one another and chat, and enjoy the food and drink that was provided. Two bunches of multi-colored balloons were anchored at either side of the raised platform. Music was provided by a harpist stationed on the right side of the platform. In keeping with the speakers’ frequent references to “religion and spirituality” and “religion or spirituality,” a pairing that implicitly contrasts institutionally organized forms of religion characterized by collective rituals and socially imposed belief systems, and highly individualized and idiosyncratic forms of personal spiritual exploration, there was very little orchestrated movement required of the participants. There was no collective recitation, no singing, no coordinated gestures. After years of schooling, everyone knew how to stand and listen attentively while the various speakers offered reflections from the lectern.

There were, however, two opportunities for coordinated practice. Large blank sheets of poster board were fastened to the walls in the various parts of the complex (the main gathering space, a small room that will eventually include a sink for ritual ablutions, a room designated for meditation with a collection of religious symbols among which individuals can select as their focus of choice, a lounge area with a couch and chairs and a kitchenette), and participants were invited to write in their ideas about how the spaces could be used or what they needed. A large mesh basket was also placed on a table in the main gathering space. Participants were invited to select from a collection of multi-colored ribbons, to write out their hopes and prayers for the future of the center, and then to thread their ribbons into the basket, with the expectation that the completed basket would be placed on display, a multi-colored weaving together of the participants’ materialized sentiments.

A few days after the ceremony, I met with Laura and we talked about the ceremony and how she understands her role as interfaith coordinator. Her plan is that anyone in the community with a UVM ID card will have free access to the center throughout the day. I asked if there would be a set of rules posted, and how center practitioners would address possible conflicts in their shared use of the space. She plans to impose as few restrictions as possible, and hopes that practitioners will learn through practice how to respectfully share the space to their mutual benefit. If conflicts occur, she will help the participants negotiate an appropriate resolution. If this seems optimistic, it is nevertheless clear that Laura is highly attuned to the ways in which religious differences, improperly addressed, can result in conflict. This is apparent from her adoption of a plastic blowfish as a kind of informal mascot for the Interfaith Center. The blowfish, or fugu in Japanese, is a highly prized culinary delicacy in Japan. Because the flesh of the fugu is highly poisonous if not properly prepared, it must be approached with knowledge and careful attention. Properly handled, it is a delight, but carelessly consumed, it is deadly. Given the poisonous discourse of religious difference that has recently dominated our public life, I believe we have good reason to celebrate the university’s new commitment to creating a safe and supportive space for members of the community to openly explore and engage their religious and spiritual commitments.

If you could write any book, what would it be?

If you could write any book, what would it be?