by Todne Thomas

“History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history. We are our history.” – James Baldwin [1]

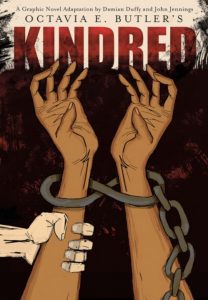

Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred Adapted by Damian Duffy and John Jennings

This month I’m reading the graphic novel version of Kindred adapted by Damian Duffy and John Jennings. Originally a novel written by the African American science fiction author Octavia Butler, Kindred tells the story of Edana, an African American protagonist who involuntarily time travels between the present and the plantation era and is forced to save her own life and intervene in the lives of her ancestors. In particular, Edana (or Dana) is catapulted to the past to save the life of her white plantation-owning ancestor Rufus Weylin and to shape the fates of her enslaved black progenitors Alice, Hagar, and Joe.

In this visual adaptation, Dana’s story emerges out of the black and white print of fiction into the colored hues of the graphic. The life Dana shares with her white husband Kevin are colored in warm creams and ambers. The palette of plantation time is more variegated and intense and increasingly consumes their regular sepia-colored present as Dana’s trips to the past last longer for days and weeks. Blues and greens evoke nature, greenery, crops, and the coolness of river water and the day sky. Evening purples and candle-light yellows color scenes of domesticity and fugitive flight. The color contrast between Edana and Kevin softened in the context of a domestic comfort (for which they also had to fight) are transferred into scenes that belie no ambiguity signaling the thickness of the color line that bracket white versus black experiences. All the myriad hues of the plantation scenery together attest to the multiple forms of violence and vulnerabilities of plantation life that were experienced by enslaved populations. The scenes of physical, sexual, verbal, and emotional abuse, of forced separations and the lived conditions of white supremacist terrorism experienced by Dana and the enslaved come off the pages via the frequent pace of their occurrence. They are many. They are undeniable, especially now because of their visuality.

Though Dana is a time traveler, her passage between a sepia present and a colored past, do not leave her unscathed. Dana is not merely a witness to plantation violence. She intervenes in the lives of plantation residents—the plantation-owning Weylins (and Rufus in particular) but most often in the lives of her black ancestors—by advocating for the enslaved and trying to prevent acts of violence, providing medical assistance to the injured, by teaching young enslaved children to read, and even sustaining physical injuries for actions that are interpreted by plantation authorities as insolence. Edana is beaten and whipped. She returns with a swollen black eye after being beaten during an early journey in which she nearly escapes rape by a slave patroller. She carries the scars from a brutal beating by a plantation overseer on her back during another passage home. During her last voyage from the past, Dana kills Rufus Weylin after he attempts to rape her, but is so quickly transported that her arm—lodged against a wall—is left behind. As spoken by Edana in the Prologue scene that opens the novel, “I lost an arm on my last trip home.” Thus, Edana’s body bears the literal marks of her confrontation with history, however supernaturally mediated. The traumas of a slave past/present are indelibly imprinted on her form. But more than that, Edana’s experiences with slavery dramatically changes her visage. Adeptly depicted in the visual novel, Dana’s demeanor alters. The increasing occurrence of resident facial expressions—stone cast face, down turned eyes, and suppressed rage—tell their own tale of enslavement; a silent story of slavery as a process that can never truly be heritable, but must be experienced, witnessed, embodied, and broadcasted via the dimming of eye lights, the slumping of shoulders that broadcast resignation.

And yet for all of Edana’s changes, somehow over the course of his coming of age, Rufus changes very little. The Weylin heir’s childish demeanor and behavior both remain. The same petulant squinting of the eyes is matched by an enduring pattern of impetuous behavior. Rufus pursues his own desires and interests for power, sex, and money with almost no concern for the human costs borne by others that result from those choices. The reliance of him and his infirmed mother (who must eventually be carried) on the bondspeople they exploit illustrate the stunting infantilizations that accompanied planter privilege. The impetuously furrowed brow of Rufus, the repetition of one-dimensional scripts that evoke, dictate, and predict pseudo-familial care on the part of slaves remain. Here, James Baldwin’s words in The Fire Next Time hold relevance.

This past, the Negro’s past; of rope, fire, torture, castration, infanticide, rape; death and humiliation; fear by day and night, fear as deep as the marrow of the bone; doubt that he was worthy of life, since everyone denied it; sorrow for his women, for his kinfolk, for his children, who needed his protection, and whom he could not protect; rage, hatred, and murder, hatred for white men so deep that if often turned against him and his own, and made all love, all trust, all joy impossible—this past, this endless struggle to achieve and reveal and confirm a human identity, human authority, yet contains, for all its horror, something very beautiful. I do not mean to be sentimental about suffering—enough is certainly as good as a feast—but people who cannot suffer can never grow up, can never discover who they are.[2]

From Baldwin’s purview, the underside of the struggle for humanity engendered in African Americans’ resistance to the abjection of blackness is the stasis of white supremacist privilege, missed opportunities for humanistic engagement, communion, and growth. For all of interventions Edana made, sometimes hurtling unwittingly across time-space continuums, to save Rufus’ life over the years, Rufus cannot manage to see Edana as kin, her labor as love, her body as her own. And because of this, this refusal of humanity, Rufus cannot be saved. Edana is a time traveler, a prophet, a healer, a teacher, even a heroine, but ultimately, Edana is not a savior. Not for lack of capacity, but because white supremacist plantocracy, for all of its imprints on slave bodies also indelible scars the characters of white beneficiaries, it is irredeemable. Neither grace nor forgiveness is available for such a non-recognition of humanity.

And, this is the truly revolutionary part of Butler’s Kindred to me as a scholar of religion and race. The novel does not present a resolution or transcendence of the experiences of the slave past, but rather a complex embodied memory that holds a solidarity for some ancestors and a rejection for those who fail to recognize their shared humanity with their descendants. Genealogy is excised, exorcised even. Anti-black violence is not absolved. In the midst of an activist context shaped by Black Lives Matter, and its queer women of color leadership’s call for a valuation of black lives and the black life matter of black bodies, this non-forgiveness for the violation of black bodies is profound. To not forgive, to not give up one’s body/sexuality for white supremacy, to defend one’s body (even from an ancestor) illustrates a thick love for self and black enfleshment in the midst of processes that threaten to commoditize and dehumanize black people. In his contemplation of black intellectual writing in the Age of Ferguson, Julius B. Fleming, Jr. asks, “What can you do when you study the shattering of your own flesh, when you teach the historical destruction of that flesh, write about it, present on it, find it tucked away in the recesses of archives the world over?”[3] For me, Butler’s Edana and Duffy and Jennings’ graphic adaptation of Kindred provides an answer through their depictions of Edana, a political and spiritual ancestress, a sankofa archetype that calls for an immanent engagement with the past in the present. More broadly, these conjoined works offer us conceptual and visual portals to excavate black history, to come face-to-face with our nation’s past, our physical and political resemblance to our ancestors in times that are mutually imprinted by anti-black violence and shaped by the metaphysics of fugitivity and freedom movements.

[1] James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro, film, directed by Raoul Peck, (2017; New York: Magnolia Pictures).

[2] James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (New York: Vintage International, 1993), 98-99.

[3] Julius B. Fleming, Jr., “Shattering Black Flesh: Black Intellectual Writing in the Age of Ferguson,” American Literary History 28 (2016): 832.