This post originally appeared on the REL131: Studies in Hindu Traditions blog. An explanation, introduction, and justification for my class’ final research project can be found here (and also here).

________________________________

Rama and Ravana’s Divine Antagonism

by Celia DeLago

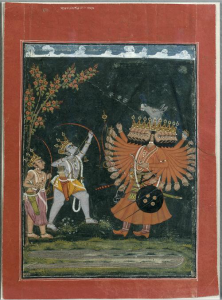

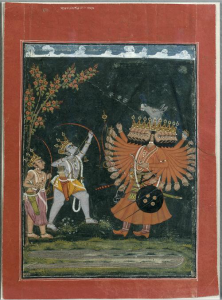

Standard depiction of Rama and Ravana’s divinely antagonistic relationship.

Through this post, I will be exploring both the mystical relationship of Ravana and Rama; as well as how their characters were viewed moralistically at the time through the use of Tulsi’s views on society; to explore how Ravana and Rama’s relationship affects how we view the deeper messages that Valmiki gave us within the Ramayana.

The symbolism of Rama and Ravana’s relationship within Buck’s Ramayana, as well as through the lens of Tulsidas’ Ramacaritmanas, conveys complex philosophical concepts, such as the nirguna (supreme formless reality) and saguna (manifestation of god in form) aspects of reality through their, at times, antagonistic guru-disciple relationship. The multifaceted relationship of Rama and Ravana is not covered in every version of the Ramayana. However, William Buck’s retelling of this epic allows us to explore their deeper relationship through poetic language.

The potential guru-disciple relationship between Rama and Ravana shapes our perception of the philosophical concepts presented within the Ramayana. The narrative of the nuanced relationship between “good” and “evil,” encapsulated in Rama and Ravana’s feud, attempts to shape our views of reality. The acknowledgment of the ambiguity of “good” and “evil,” accentuated and played with by an eternal, infinite timeline, encourages and, at times, forces the reader to open their minds to a deeper understanding of reality. The infinite change that occurs as a result of the infinite timelines of the various deities leaves much room for the changing and developing of characters. The use of themes like telepathic communication, divine powers and mystical experience among the deities gives the readers a glimpse into the deeper, “true” reality beyond the epic of these characters. Ultimately, Ravana is defeated by Rama. Suka delivers a stone from Ravana to Rama, and we learn that Ravana is actually Rama’s devotee. Ravana lauds Rama as Lord Narayana, as the Supreme, and reveals that even while Rama is unaware that he is secretly a deity, Ravana has been aware all along, because his bhakti towards Rama and his desire to attain moksha through devotion to Rama has allowed him to always see Rama’s true form. Rama dismisses this revelation out-of-hand; and through this seemingly simple gesture, the dharma of Ravana is perfected and completed, as Rama lives on as king of Ayodhya (Buck).

As a cultural observation: I decided to Google phrases such as “Rama’s negative qualities” while doing research for this paper. Many people posted questions previously such as, “Why is Ravana considered evil?,” “What are some of Rama’s negative traits?,” etc. Here were some interesting responses that I found.

We can acknowledge the goodness within Ravana, and the lack of moral integrity and humanity within Rama; And ultimately, we must acknowledge their deeper relationship. Ravana’s goodness is highlighted and emphasized at important times (often before he is beaten down by humility once again). Ravana earned his boon through engaging in austerities for almost 10,000 years to Lord Shiva; was released from Lord Vishnu’s mountain-cage for his beautiful songs; and, ultimately, confessed his sincere guru-devotion to Rama (12, 35, 350-351 Buck). On the other hand, Rama engages in mutual deformation of Surpanakha and disrespect to Ravana; and continually treated Sita in reprehensible ways, requiring her to undergo Agni Pariksha (trial by fire), and ultimately banishing her while she is pregnant with two children (Buck).

The morality (and amorality) of both Rama and Ravana shapes the applicability of these concepts to our own lives: we may be intrigued by Ravana’s asceticism or beautiful singing, but his actions, such as killing the virtuous, saintly Vulture King Jatayu, may make us question the efficacy of, say, certain rituals, or moralistic beliefs and alliances. These multifaceted characters exist as animate representations of important archetypes and symbols found, for example, within various religious traditions: the duality of the yin-yang, as well as the tomoe; the boisterous behavior of the Greek and Roman gods, etc. Humans can relate to characters that have many facets, who fail and act in evil ways but also strive for goodness.

It is also important to investigate the ethics and morality of Ravana and Rama, informed by Tulsidas’ approach to society and his views on ethical, spiritual and social qualities found within Savitra Chandra’s article on Hindu social life (49, Chandra). Evaluating the characters of the Ramayana through the lens of the cultural attitudes of the time, we can gain a better understanding of how norms shaped the epic and thus informed cultural attitudes. It is easy to display some of the strange cognitive dissonance that seemingly comprises most of the characters in the Ramayana: Rama is held as the ultimate, the Supreme, but still performs actions that are deplorable. Ravana is a rapist, a misogynist and a murderer, as well as being a previously-devout ascetic for almost 10,000 years. The complexity of these characters affects how we interpret the philosophical concepts of Buck’s Ramayana by giving us these messages through questionable characters.

In Chandra’s “Two Aspects of Hindu Social Life and Thought,” we learned that, although Tulsidas was a bhakti devotee of Rama, a man considered a saint, he also held worrisome views about his basis of qualifying members of society (49, Chandra). Through Chandra’s description of uttam, we can conclude Rama falls within the high first category, and had obviously lorded over Ram-Rajya (the kingdom of Ram; the greatest kingdom in history before the fall into Kali Yuga): “The ethical and spiritual qualities…include humility, absence of arrogance, straightforwardness, equanimity, lack of attachment to worldly things, and above all, a sense of discrimination or understanding of good and bad” (49, Chandra). Chandra goes on to say that “Tulsi includes good rulers and their agents in the category of uttam” (Chandra, 50). Rama also committed negative deeds, towards Ravana and his sister Surpanakha, in a way that was lacking in humility. To summarize: “He seems utterly unaware of having done Ravana any harm” (97, Goldman).

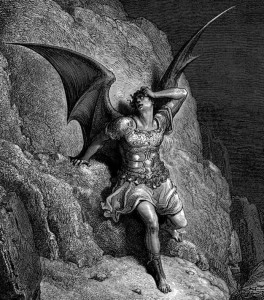

It is also hard to decipher where Ravana belongs within Tulsi’s view of society. Chandra  discusses nich, a person of low quality or status who needs to be kept firmly under control (Chandra, 52). We may very easily draw this parallel to Ravana, who is portrayed as the lowest of the low throughout the epic. We, as the readers, are encouraged to hate Ravana from the beginning solely based on the title of the epic. But Ravana is not evil through and through; Ravana is more akin to Satan, a fallen angel capable of goodness but prescribed by the fates to committing negative deeds until his death. At the same time, however, Ravana, like Rama, ruled over a kingdom (Lanka), and had devoted servants. He was born a Brahmin, and was an ascetic devotee of Lord Shiva.

discusses nich, a person of low quality or status who needs to be kept firmly under control (Chandra, 52). We may very easily draw this parallel to Ravana, who is portrayed as the lowest of the low throughout the epic. We, as the readers, are encouraged to hate Ravana from the beginning solely based on the title of the epic. But Ravana is not evil through and through; Ravana is more akin to Satan, a fallen angel capable of goodness but prescribed by the fates to committing negative deeds until his death. At the same time, however, Ravana, like Rama, ruled over a kingdom (Lanka), and had devoted servants. He was born a Brahmin, and was an ascetic devotee of Lord Shiva.

Interestingly enough, those who would be considered nich by Tulsi have come to express sympathy for Ravana, often as a political gesture against oppression:

“Glorification of Ravana is not unknown. According to a minor tradition, the demons of Vishnu are successive reincarnations of his attendants, who take this form in order to be near him…In modern times, Tamil groups who oppose what they believe to be the political domination of southern India by the north view the story of Rama as an example of the Sanskritization and cultural repression of the south and express their sympathies for Ravana and against Rama.” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Ravana has been utilized as a cultural, political symbol that extends beyond his original intended purpose within the myth, and for good reason. If we cannot clearly decipher the moral integrity of the designated antagonist, it is fair to say that we cannot trust that the appointed protagonist is worthy of our admiration.

Bibliography:

1.Eck, Diana. Darśan. New York: Columbia University Press. 1998.

2. Buck, William, and Vālmīki. Ramayana. Berkeley: University of California, 1976.

3. Velchuru Narayana Rao,“Rāmāyaṇa,” in Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd Edition, ed. Lindsay Jones (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005), 7616-7618.

4. Rama and Lakshmana Fighting Ravana (India, Pahari, Bilaspur School). 1750. Painting. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Edward L. Whittemore Fund, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

5. Savitri Chandra, “Two Aspects of Hindu Social Life and Thought, as Reflected in the Works of Tulsidas,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Feb., 1976), pp. 48-60.

6. Goldman, R., and J. Masson. “Who Knows Ravana?–A Narrative Difficulty in the Valmiki Ramayana.” Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 50.1/4 (1969): 95-100. JSTOR. Web. http://www.jstor.org/stable/416942

7. McCrea, Lawrence. 2010. “Poetry beyond good and evil: Bilhaṇa and the tradition of patron-centered court epic.” Journal Of Indian Philosophy 38, no. 5: 503-518. ATLA Religion Database, EBSCOhost (accessed October 24, 2014).

Hyperlink Bibliography:

8. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Ravana.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2014. .

9. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Rama (Hindu Deity).” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2014. .

10. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Tulsidas.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2014. .

11. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Ramayana (Indian Epic).” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2014. .

12. “Ramcharitmanas.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 19 Nov. 2014. .

13. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guru-shishya_tradition

14. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/653297/yinyang

15. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/585989/telepathy

- http://symboldictionary.net/?p=1660

17. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/244670/Greek-mythology

18. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/507866/Roman-religion

19. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/63933/bhakti

20. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/387852/moksha

21. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surpanakha

22. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lanka

23.http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/90/GustaveDoreParadiseLostSatanProfile.jpg

evance of work by UVM faculty, students, and alumni. It featured a number of Religion Department faculty!

evance of work by UVM faculty, students, and alumni. It featured a number of Religion Department faculty!

I have an almost-two year old daughter, and she has a legion of Nanas, Pop-Pops, Grandmas, Grandpas, Aunties, Uncles, and general well-wishers who love buying things for her. (This is lovely and appreciated, even if often roundly met with frustration: Please bring less stuff into my house. Please.) In the midst of a now-typical “But, seriously, what does she need?!” conversation,

I have an almost-two year old daughter, and she has a legion of Nanas, Pop-Pops, Grandmas, Grandpas, Aunties, Uncles, and general well-wishers who love buying things for her. (This is lovely and appreciated, even if often roundly met with frustration: Please bring less stuff into my house. Please.) In the midst of a now-typical “But, seriously, what does she need?!” conversation,