Thank you to Katherine Merrill, Senior Lecturer in Mathematics & Statistics, for contributing this post.

As an avid learner, I have always been amazed at students who think that the instructor is solely responsible for their learning. And this is especially so for an online course.

In the past, I have used Discussion Boards to solicit and encourage communication between the students and with myself. However, I noticed that students do not want to bare their souls in a discussion board. And I as the instructor needed more sharing of their experience, rather than through frantic urgent emails. I decided to try the Journal tool in Blackboard because it provides a communication tool between each student and the instructor preserving privacy.

In Blackboard, I created a journal titled, “Your Private Journal.” Here are the instructions for the journal assignment:

Hi. This is where we’re going to spend time together and build a successful strategy for completing this course. Here are the types of journal entries I want you to make:

- INTRODUCTION – PLEASE TELL ME ABOUT YOURSELF

- Where are you located while taking this course?

- What does your schedule look like for the next 6 weeks (other courses, work, plans to be offline)?

- What is your major/area of study and why are you taking this course?

- Tell me about your family, pets, etc.

- What do you like to do for an avocation or any special interests that you have?

- After reading the chapter and watching the lecture videos:

- Post a new concept/idea for you that is cool or post an idea that you need help.

- After tackling the practice problems

- Post what problems you did (just list by number)

- Post about the problem(s) that gave you the most difficulty to work out or that you still need to understand

- After taking the QUIZ and EXAM

- Post a reflection about the problems that you got wrong and how to do them correctly (or ask for help)

- Weekly post a self-reflection about the material and what’s going on with you (really busy, or whatever)

Basically, I am looking for you to comment on the materials each week. For example in Week 1, comment on your work for Chapter 1, Sections 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 including YOUR WORK TO PREPARE FOR THE QUIZ (READING THE BOOK, THE RECITATION PROBLEMS, ANY EXTRA PROBLEMS), A REVIEW OF THE QUIZ, (WHAT YOU GOT WRONG AND HOW TO DO IT CORRECTLY, OR ASK FOR HELP), AND FINALLY A REVIEW OF THE EXAM.

As for grading, I created a spreadsheet with columns representing two possible points for each week’s entries. I just did a check mark for each item required for the week. If there was no entry, the student received a zero. If they did part of the work, the student received a one. If they did it correctly and completely, they earned two points.

Yes, it was a lot of work. I was committed to reviewing every detail of their writing, including correct use of vocabulary and content. I also showed interest in them as they struggled with time-management of coursework, internships, summer jobs, and family commitments. BUT IT HAD A HUGE PAYOFF. The students enjoyed the course and course evaluations were improved. Most importantly, I felt like they were getting the attention they deserved AND they were developing good learning habits by reviewing their work.

This summer, I revisited the excellent book Discussion as a Way of Teaching: Tools and Techniques for Democratic Classrooms by Stephen D. Brookfield and Stephen Preskill. I’d like to share some key ideas from their text (and encourage you to check out the book from the Bailey/Howe collections).

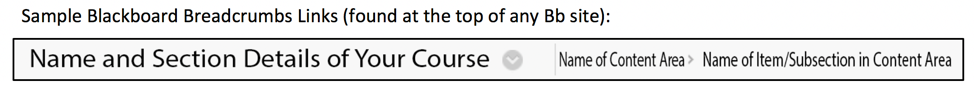

This summer, I revisited the excellent book Discussion as a Way of Teaching: Tools and Techniques for Democratic Classrooms by Stephen D. Brookfield and Stephen Preskill. I’d like to share some key ideas from their text (and encourage you to check out the book from the Bailey/Howe collections). I’ve only recently begun working at UVM, which means, like many folks out there, I’m learning Blackboard (Bb), made perhaps more challenging for me by having vigorously used Moodle for the past eight years!

I’ve only recently begun working at UVM, which means, like many folks out there, I’m learning Blackboard (Bb), made perhaps more challenging for me by having vigorously used Moodle for the past eight years!

ible when you hover) is the gateway to the editing menu for any previously created Bb item, file, link, tool, etc.

ible when you hover) is the gateway to the editing menu for any previously created Bb item, file, link, tool, etc.

Do you frequently attend meetings where technology is banned? I don’t. In fact, technology plays an important role in most of the meetings of which I am a part. On laptops, each participant can view the agenda and related documents. On cell phones, we can text a committee member who’s running late without interrupting the whole group. Using shared documents, we can co-create outlines or projects. Using online project management tools, we can develop a detailed plan.

Do you frequently attend meetings where technology is banned? I don’t. In fact, technology plays an important role in most of the meetings of which I am a part. On laptops, each participant can view the agenda and related documents. On cell phones, we can text a committee member who’s running late without interrupting the whole group. Using shared documents, we can co-create outlines or projects. Using online project management tools, we can develop a detailed plan.