I’m delighted to formally announce that I have accepted an offer to take up the position of J. S. Woodsworth Chair in the Humanities at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, beginning next year. (Simon Fraser recently, once again, took the top spot among comprehensive universities in Macleans’ Canadian university rankings.)

The chair is named after J. S. Woodsworth (1874-1942), a prominent Canadian activist-intellectual, pacifist and labor campaigner, co-founder and first leader of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF, predecessor of today’s New Democratic Party), co-architect of Canada’s social-welfare system, and minister (the robed type) who was part of the Social Gospel movement. It will be a great honor to represent these aspects of his legacy and to follow in the footsteps of previous chair holders Eleanor Stebner, Ed Broadbent, and Alan Whitehorn.

At the same time, Woodsworth happened to espouse some views that were widespread in Canada’s early twentieth century left, but which today’s left rightly abjures. Specifically, he was an ardent supporter of eugenics, and, at least in his early writings, ethnocentric, xenophobic, and, by our standards, racist. (Among those he was most concerned about were Ukrainians, two of whom eventually came to Canada and gave birth to me.)

Representatives of the Woodsworth legacy, such as the college named after him at the University of Toronto (which I attended briefly as an undergraduate), have largely been either unaware or not forthcoming with this information. To date, for instance, his Wikipedia page makes no mention of it; nor does the 2015 online edition of The Canadian Encyclopedia. It was also not known to me when I accepted the position a few months ago. Yet it is evident to readers of his 1909 book Strangers Within Our Gates, about which its 1972 editor Marilyn Barber writes, “the gospel of love was subordinate to the gospel of nationalism.” In no respect do I intend to continue that part of his legacy (and, to be fair, Woodsworth’s own views changed over time).

I take the fact that I was selected for the Woodsworth Chair as indicative of Simon Fraser University’s recognition of the value of the kind of engaged eco-humanities work I have been carrying out at the University of Vermont, including as Steven Rubenstein Professor. The Woodsworth Chair will allow me to focus my teaching and scholarship on this kind of work, and will support me to do scholarly as well as extra-academic outreach around it. Below I share a vision statement I’m developing to guide my work in this exciting position.

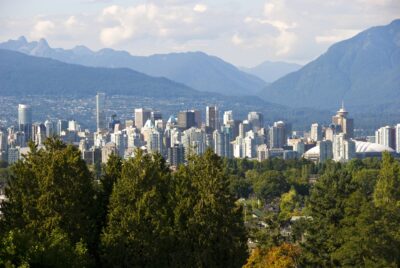

Moving to Vancouver will also represent a return to the Canada that I grew up in. Vancouver is a beautiful metropolis with diverse communities and many exciting initiatives to interface with, including SFU’s Institute for the Humanities, its Digital Democracies Institute, UBC’s Centre for Climate Justice (co-directed by Naomi Klein), and highly engaged Indigenous communities that I hope to learn from and in some way support.

That said, Canada is not exactly the same country I left twenty-three years ago. (For one thing, Metro Vancouver’s European descended population has gone down from about 80-90% in my youth to 43% today.) Canada continues to change, as should the evaluation of its historical personages — including Woodsworth and, for that matter, explorer and fur trader Simon Fraser, after whom the University and the 1,375 km long river (Sto:lo, in Halq’emeylem) that drains much of southwestern British Columbia are named.

I welcome these changes as I take up the challenge of representing the many still vital and relevant dimensions of the Woodsworth legacy.

Vision statement

As incoming J. S. Woodsworth Chair in the Humanities, I plan to focus my scholarship, teaching, and community outreach around three critical challenges to the (purportedly) universalist humanism that underlies the modern humanities. By that I mean the idea that humanity as a unified whole embodies certain understandings and values associated with “the human” and its distinctiveness from all else. Two of these challenges are historically deeply warranted. The third is new and requires novel forms of critical interrogation.

1. The decolonial challenge: As they emerged within Western intellectual institutions, the humanities have embodied a Eurocentrism that has long been questioned by anti-colonial, decolonial, and postcolonial movements around the world. (It is this that is reflected in the SFU Department of Humanities’ recent rebranding as the Department of Global Humanities.) Decolonial thinking, which asserts that the adverse legacies of coloniality are still with us, is being applied within educational, cultural, and other institutions, yet its application requires nuanced understanding of the varying contexts shaped by divergent histories of imperial conquest, colonial rule, and cultural and ecological disruption. These are hardly the same in settler-colonial countries like Canada and the U.S. as they are in Latin America, Africa, South and East Asia, the Near East (including the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict), Russian-colonial Eurasia, and in Europe itself. How do we find viable convergences between humanist legacies and decolonial critiques in a world becoming increasingly unruly and arguably multipolar?

2. The ecological challenge: Whilst the humanities have focused on human meaning-making activities, the ecological sciences and the environmental and animal welfare movements have insisted that meaning has never been exclusive to humans, and that understanding the world always involves understanding and interacting with other beings. This second challenge is deeply intertwined with the first insofar as Indigenous and traditional peoples, by their very existence, embody a critique of the anthropocentric humanism (or “human exceptionalism”) that has conceptually detached humans from their more-than-human relational contexts. Addressing current challenges such as rapid climate change, species extinction, and ecological disruption requires an understanding of human communities’ intimate entanglements within multispecies, ecological relations. In light of the varied ways in which humanisms have emerged from, adapted to, embodied, and overcome their more-than-human contexts, how can the global humanities become eco-humanities?

3. The digital challenge: This third challenge is represented by the growing centrality to contemporary life of digital media, artificial intelligence, and algorithmic forms of governance. If the first two challenges are grounded within legitimate and urgent concerns around equity and social and ecological sustainability, this challenge has grown less from the pursuit of common human interests than the pursuit of profit, as embodied in the greatest wave of wealth-making in the history of modern capitalism. In the space of a couple of decades, tech companies have become among the world’s most powerful and their leaders among the wealthiest individuals the world has ever seen. (The wealth disparities they represent are among the things J. S. Woodsworth would certainly militate against today.) How do digital “rationalities” challenge human capacities to govern our lives in accordance with collectively chosen values? How can the “wild west” of social media be reined in toward serving the public rather than short-term private interests?

Each of these challenges has, in some circles, become associated with ideas of “posthumanism” and the “posthumanities,” though it is not always clear in what sense they are “post” and in what sense they extend and build upon existing concepts of humanity and humanism. As Woodsworth Chair, I intend to articulate not only what they are “post” to, but what they might become “pre” to: what kind of common humanity can we build that avoids the pitfalls of colonialism, ethnocentrism, anthropocentrism, and technologically driven, extractive and accumulative capitalism? And how can artistic and cultural creativity contribute to the forging of such a common humanity?

Answering these questions, in a world becoming culturally more charged, politically more volatile, and climatically and ecologically unhinged, will require dialogue across chasms of difference. That requires open, public spaces in which such dialogue can take place. It also calls for creative and open-ended experimentation in the forms that dialogue takes, as well as the challenging of conventions, sacred cows, and predetermined destinations.

I look forward to working toward these goals within my capacity as Woodsworth Chair.

congrats, sound like a good gig and a lovely part of the world to live in

Congratulations Adrian, and i’m looking forward to your return to Canada! Your vision statement is inspiring.

Thanks, Gary and dmf. It is a lovely part of the world, and will be nice to be back in Canada. Your support is appreciated!

Dear Adrian

I am a filmmaker and academic from Chennai, India. I just went through the introduction to your book ‘Ecologies of the Moving Image’ and I was completed bowled over! I cannot lay claims to any deep research in the academic field of film language but as a practicing filmmaker I, along with many others, am deeply concerned about the impact that colonial modes of image articulation continues in our cinema. Worse, despite having a rather strong tradition in literature/ poetry/ music and dance, our films seem to have ignored all of that as an integral part of an ‘Indian Ecology’ and gone on to mimic Hollywood or at best, the kind of cinema that the European triumvirate- Berlin, Cannes and Venice support as ‘worthy’.

I would like to explore this conundrum to the best of my abilities. And if there is anyway you can guide me I would be deeply obliged.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K._Hariharan_(director)

with warm regards

Hariharan

Dear Hariharan – Thanks for writing. I’m glad to hear that Ecologies of the Moving Image interests you. Please let me know (at aivakhiv@sfu.ca) if you’d like a PDF of the book, which I’d be happy to send you by email. While my familiarity with Indian cinema is only superficial, I’d be happy to converse further about your work, the book, and the topic of decolonizing cinema and visual media (which I’ve continued exploring and writing about since then).

All best,

Adrian

Dear Adrian

Thanks. I haven mailed you as suggested.

Thanks again for your kind reply

warm regards

Harihara