This post is in response to questions often asked by my students. ‘What tunes should I practice during my summer break from lessons?’, they ask. Or: ‘How can I get better at learning tunes from a fake book chart (i.e., just melody line with chord symbols above)?’ One way to begin working toward these goals is to expand your knowledge of major scale key signatures and fingerings, and major ii-V-I progressions, to the point where you are familiar with these skills in all twelve keys.

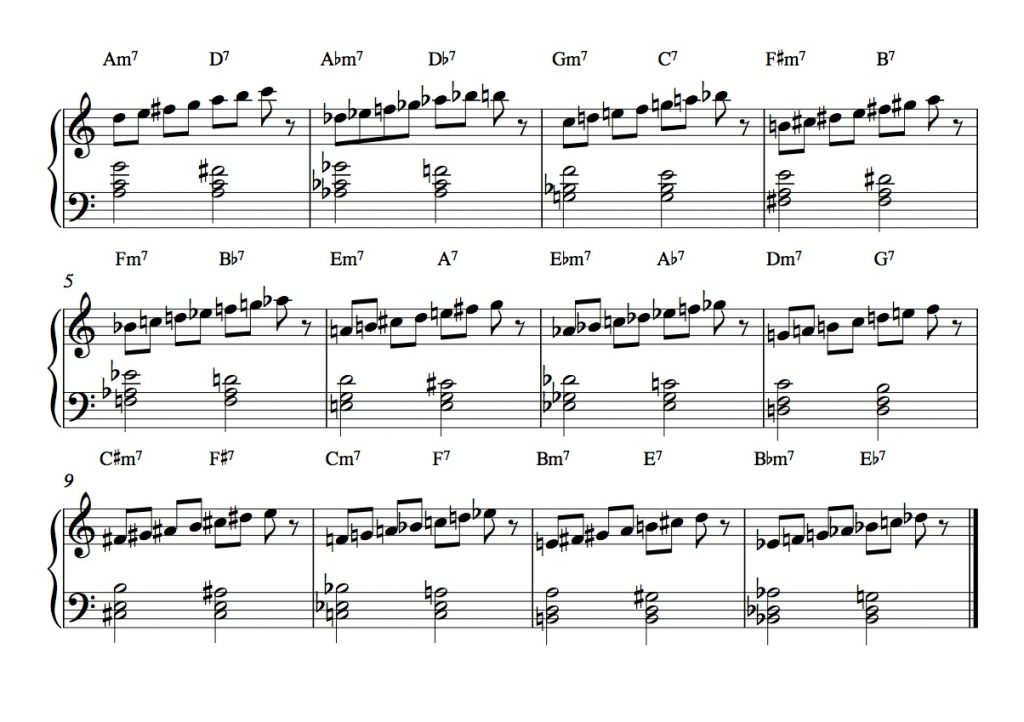

‘Learn it in all twelve keys!’ is common refrain in jazz education which often makes it sound like a student should learn a tune or a melodic pattern or a voicing in all twelve keys at one sitting. While this can be valuable, it is also important to relate such concepts to the context of a tune. With this thought in mind, I have found a number of tunes in The Real Book (Volume 1, sixth edition, published by Hal Leonard) that use the major ii-V-I progression in at least three keys and so are good exercises in constructing voicings for the progression in those keys. I have come up with a tune list that allows one to learn major ii-V-I progressions in all twelve keys through learning a series of six tunes. You can assemble your own list of six tunes through making various combinations of tunes that I have outlined below. The only tune one has to learn to complete this series is the Miles Davis and Eddie Vinson’s Tune Up; other than that, one can assemble the list according to one’s preferences. There are tune options that follow more of a modern jazz/bop direction (which may be more of interest to players interested in instrumental performance) and others that follow more of a ‘standard tune’ direction (which may be more of interest to those interested in singing and vocal accompanying.)

Learn one tune each from Group 1 and Group 2 (starting with either group). These groups include the keys that pianists usually learn first, as they have more straightforward fingering (i.e., RH starts on the thumb, etc.) Once you have learned these two tunes and the six keys through which they move, you can learn one of the pairs of tunes in Group 3 and one of the pairs in Group 4. The tunes in these later groups begin in the more basic keys introduced by the first two groups and modulate into keys with more challenging fingerings and ‘keyboard topography’. When you finish the group of six tunes, you will have learned the major ii-V-I progression in all twelve keys.

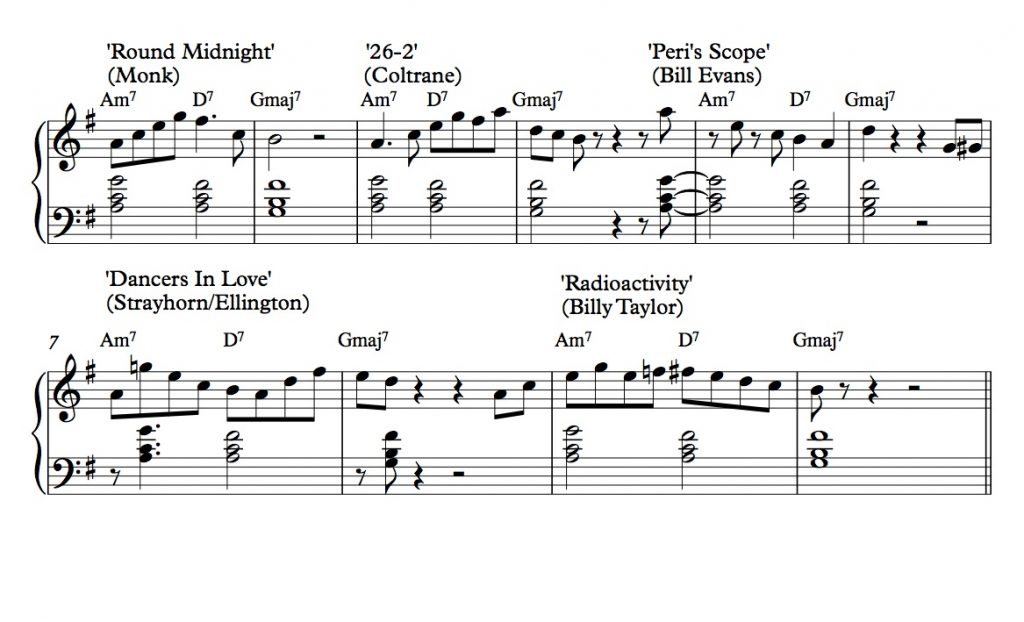

Group 1 – keys of G, F, Eb (keys shown in exercise) – choose one of three tunes: Laura (not in Real Book Volume One), Ornithology or How High the Moon

Group 2 – keys of D, C, Bb – one tune – learn Tune Up

Group 3 – Db, B, A– learn Solar (includes ii-V-I in Db) and

Cherokee (includes ii-V-I in B and A; if root position voicing is used, some larger shifts in LH voicings are required, so rootless voicings can be helpful with this tune.) alternate pair: One Note Samba (includes ii-V-I in Db and B) and I Love You (includes ii-V-I in A)

Group 4 – keys of Ab, Gb, E – learn I’ll Remember April

(key of G) and Broadway (key of Eb). For a more challenging pair, try All The Things You Are and Recordame.

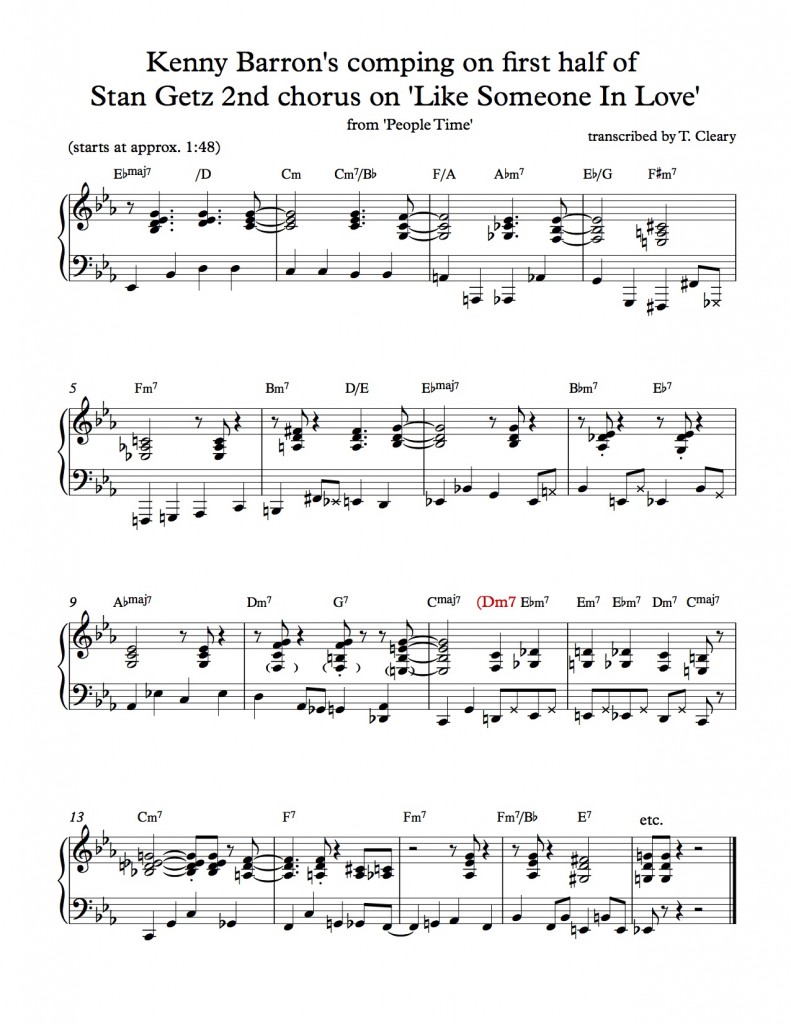

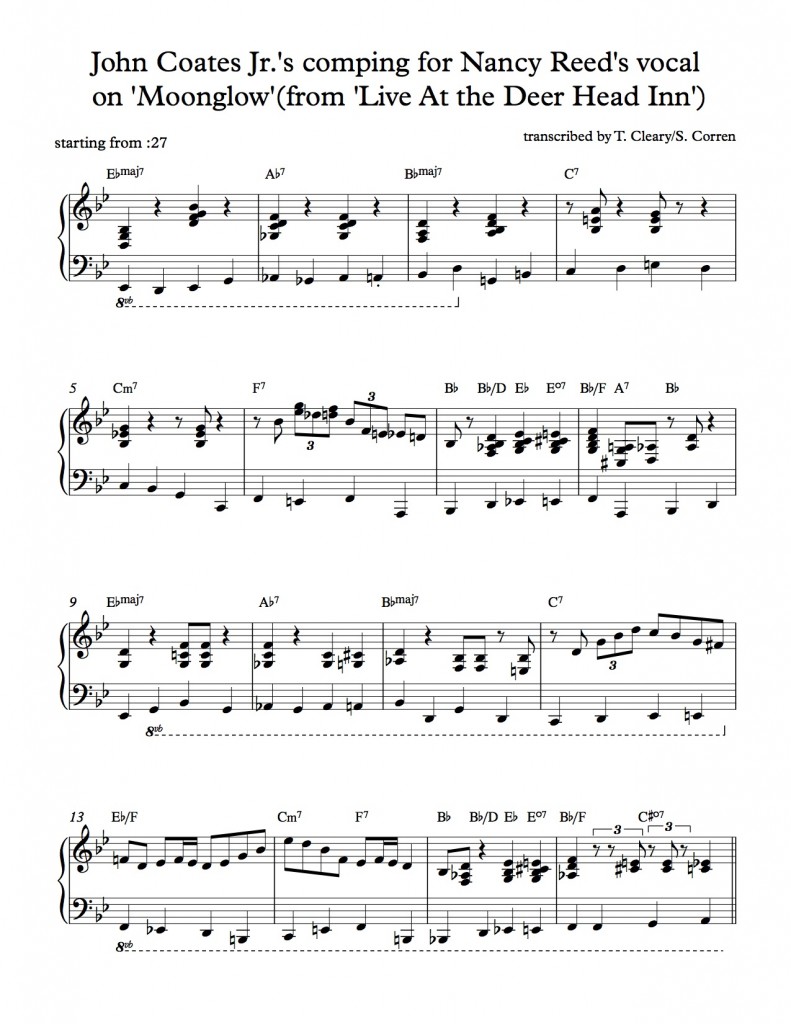

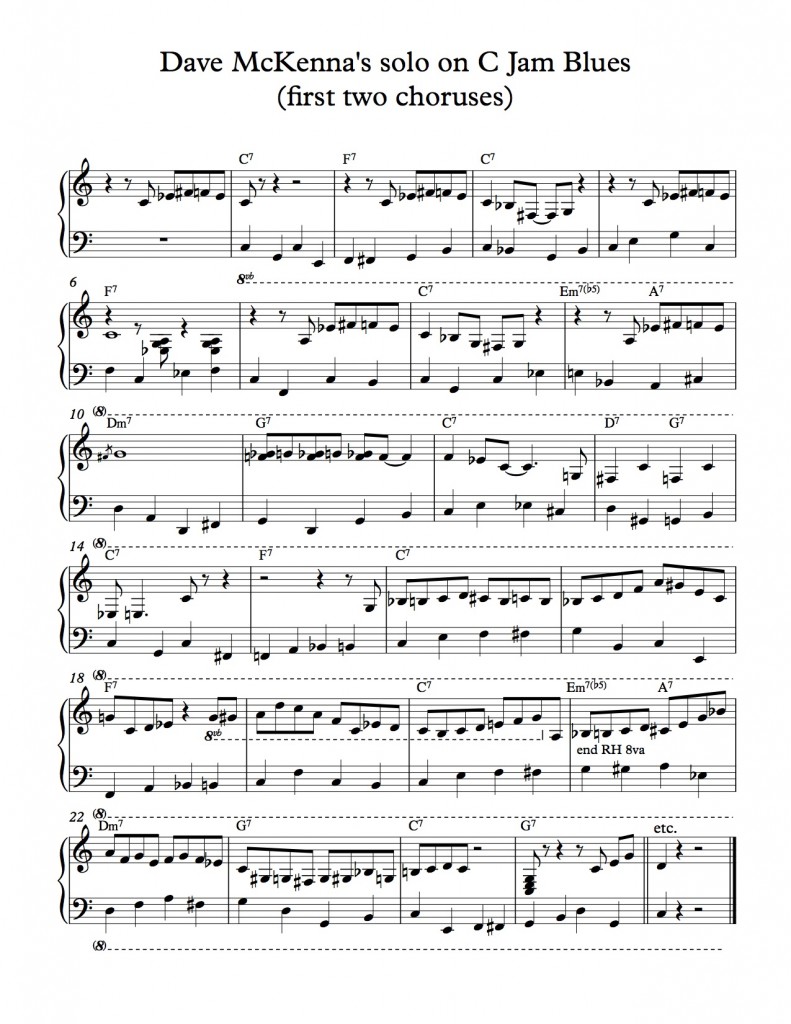

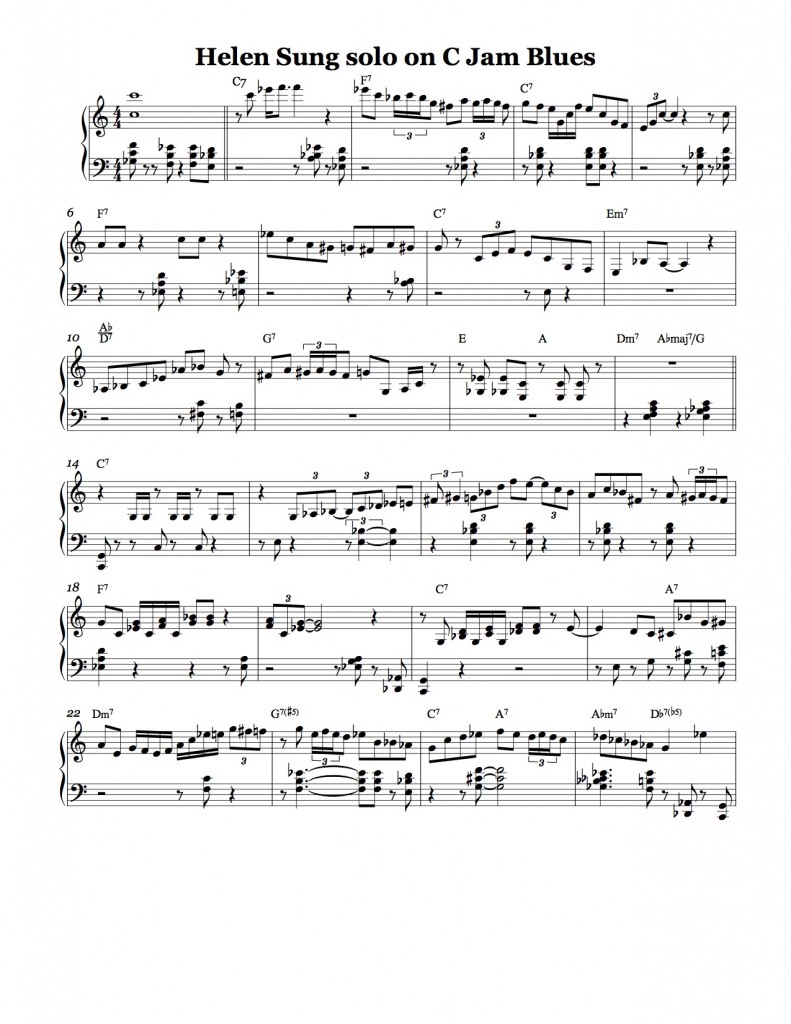

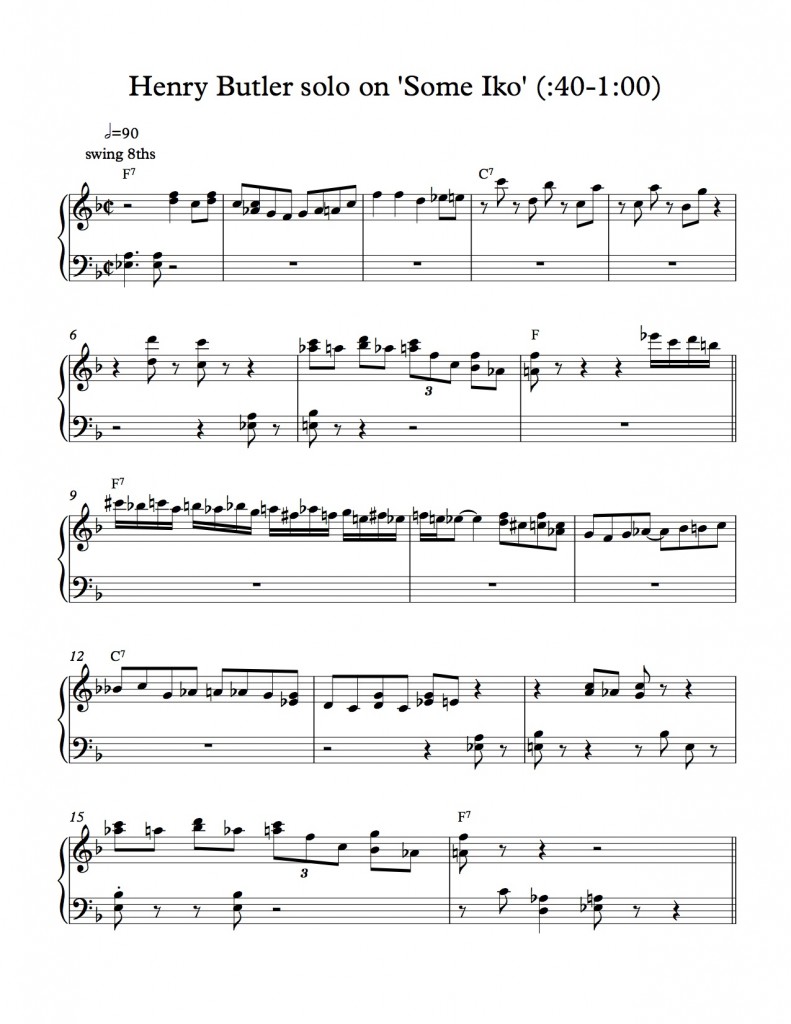

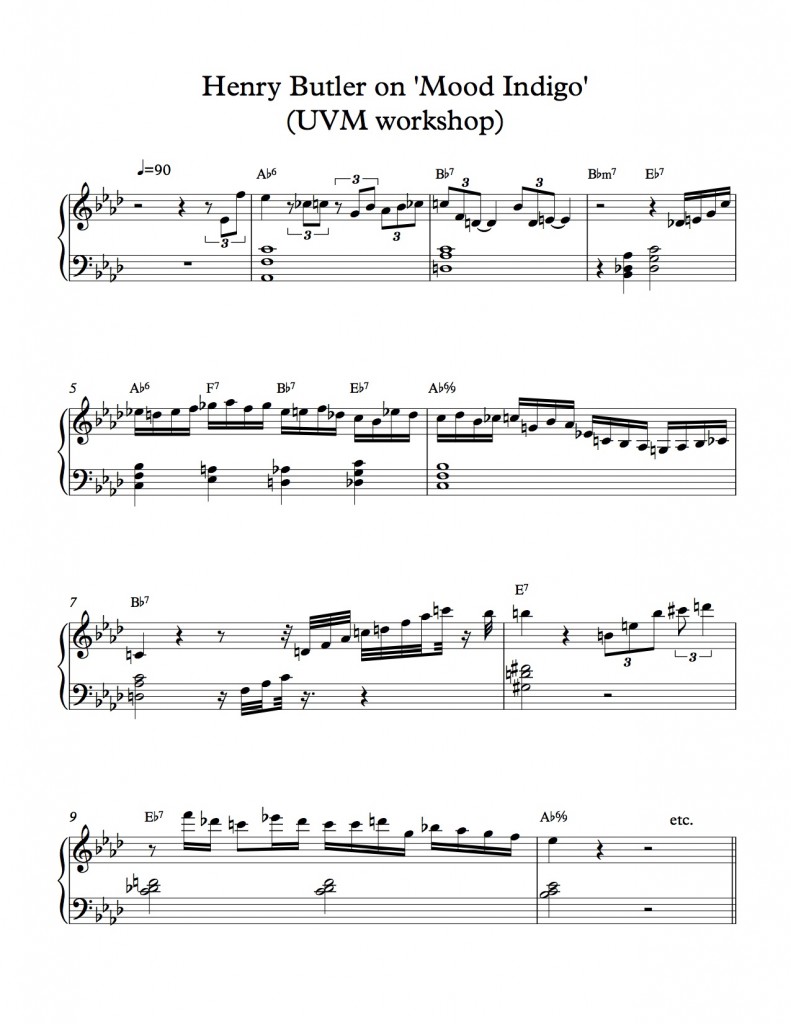

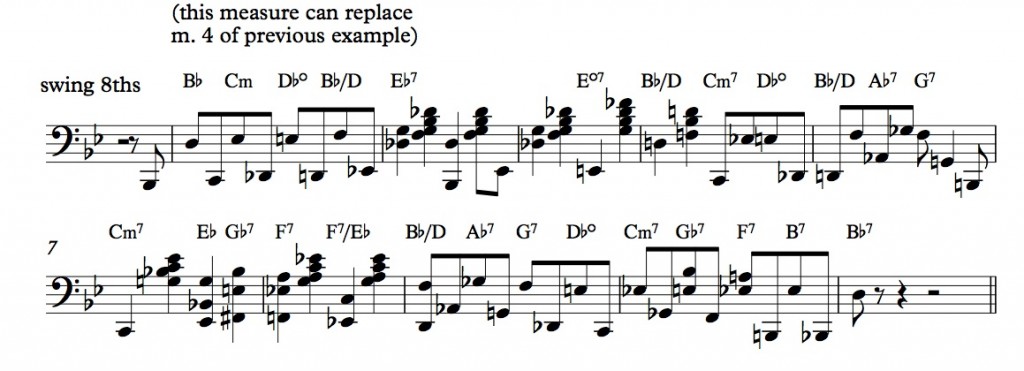

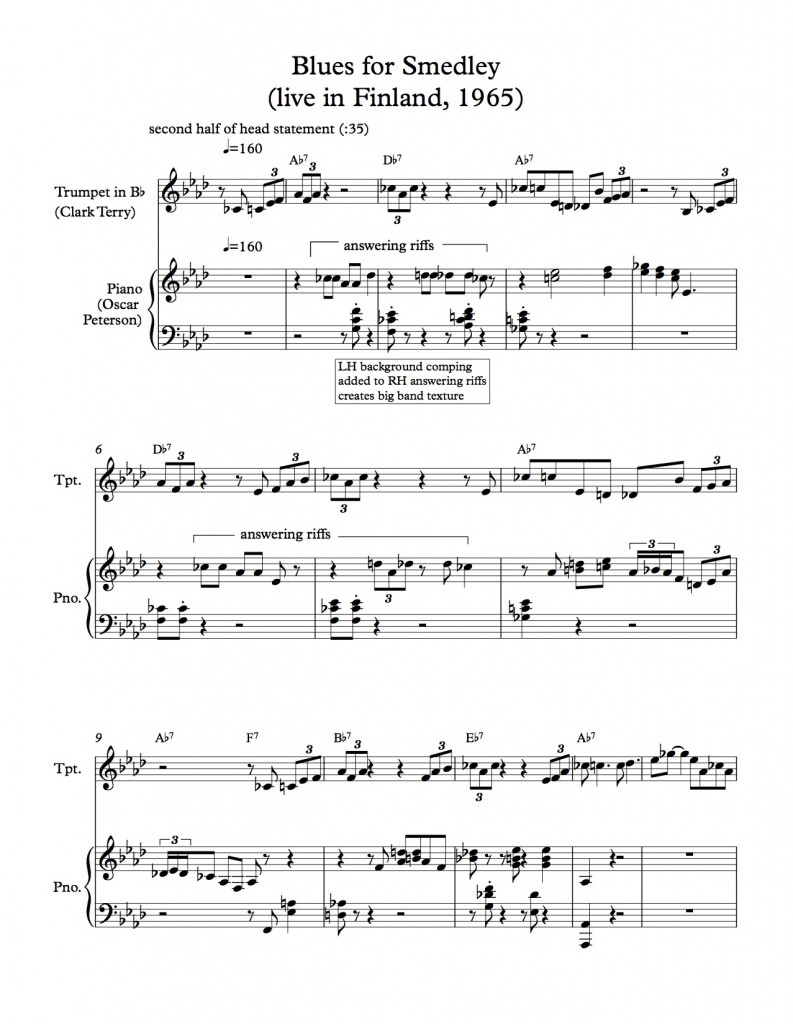

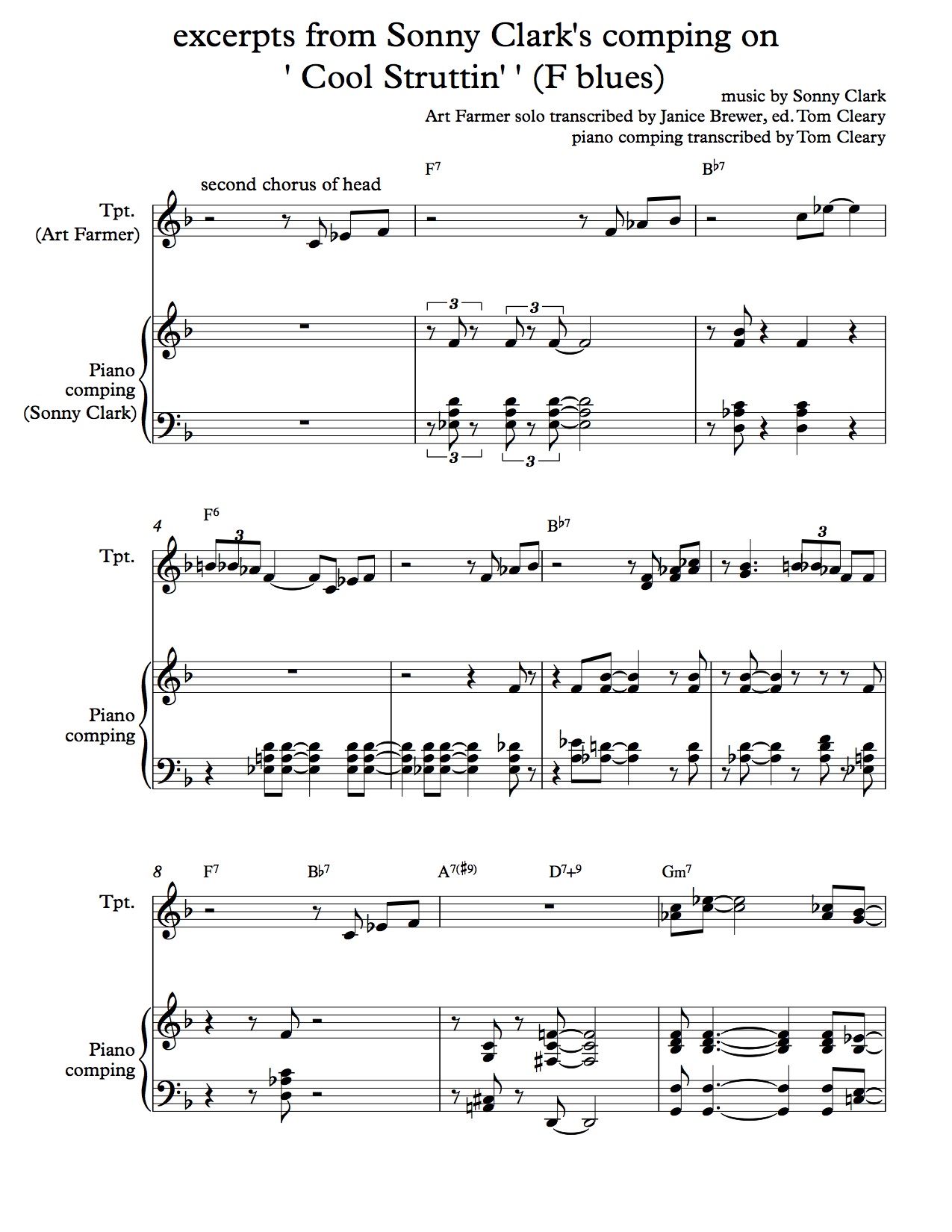

When learning any jazz tune, it is crucial to have access not just to a chart but to a recorded version by a jazz player or singer that demonstrates how to interpret the melody with both rhythmic creativity (i.e. using a swing or Latin rhythmic approach) and melodic creativity (i.e. adding melodic ornaments and fills), as well as how to incorporate improvisation (through improvised sections of various lengths, from fills between melody phrases to half or full chorus solos.) With the tunes on this list in particular, it is helpful to practice chordal comping with one or two hands and without playing the melody, along with a recorded version in the ‘book key’ at a moderate tempo. Below are some suggestions of recordings of this type to use. Not only do the tempos of these versions make them well suited for practicing, but the soloists on them model how to give a jazz interpretation to a relatively simple melody (with the exception of Sonny Rollins, who solos on ‘All The Things’ with only tangential references to the head.)

How High The Moon – Chet Baker from ‘Chet’ album

I Love You – Mick Hucknall (from soundtrack to the Cole Porter bio-pic ‘De-Lovely’) – not a jazz version, but it uses the same changes as the Real Book, and has a good practice tempo.

Laura – Charlie Parker with Strings (on this version, there is a five-and-a-half-bar orchestral introduction; Bird enters with the melody at :23.)

Tune Up – Miles Davis version from ‘Blue Haze’ album

All The Things You Are – Sonny Rollins version from ‘A Night At The Village Vanguard’ (on this piano-less record, Rollins begins, after a two-bar count off, by improvising on the changes rather than stating the melody, so this is a great recording to use for practicing changes)

Broadway – Art Pepper and Ted Brown featuring Warne Marsh

Recordame – Bobby Hutcherson

One Note Samba – Coleman Hawkins (from Desafinado) – this version uses a different progression (just the Dm7, Db7, Cm7, B7 changes sped up to two beats each) on bar 13 and 14 of the form, but otherwise uses the same changes as the Real Book.

Cherokee – Modern Jazz Quartet with Wynton Marsalis

I’ll Remember April – Chet Baker (1956 version)

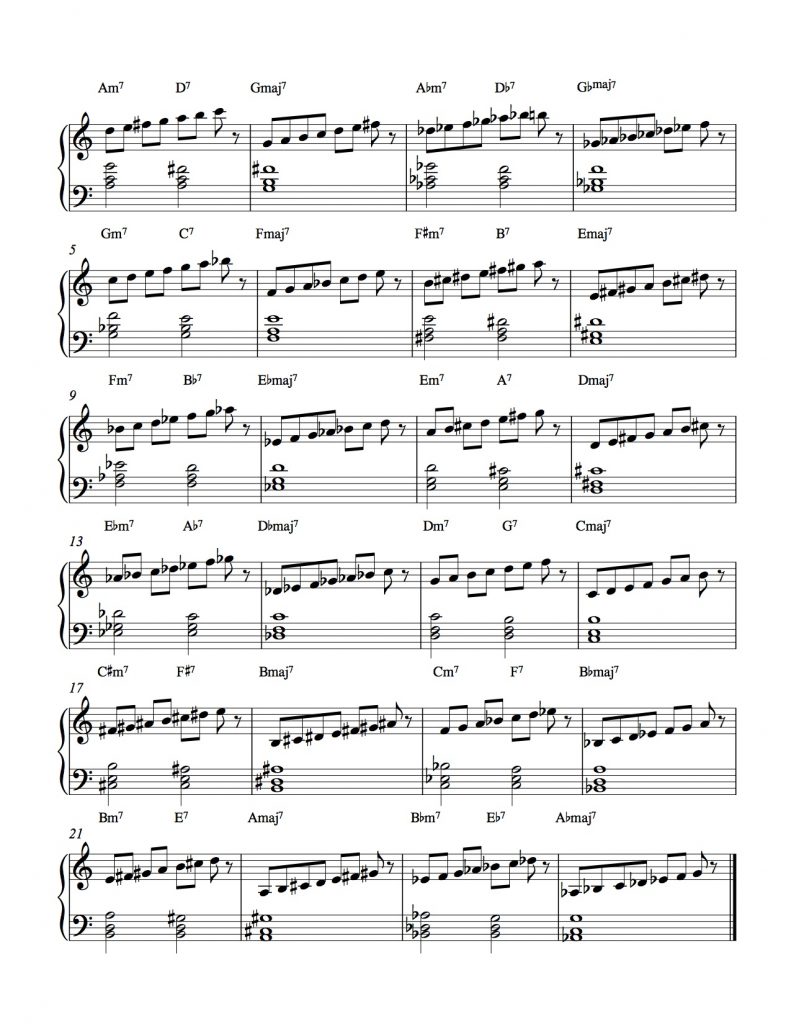

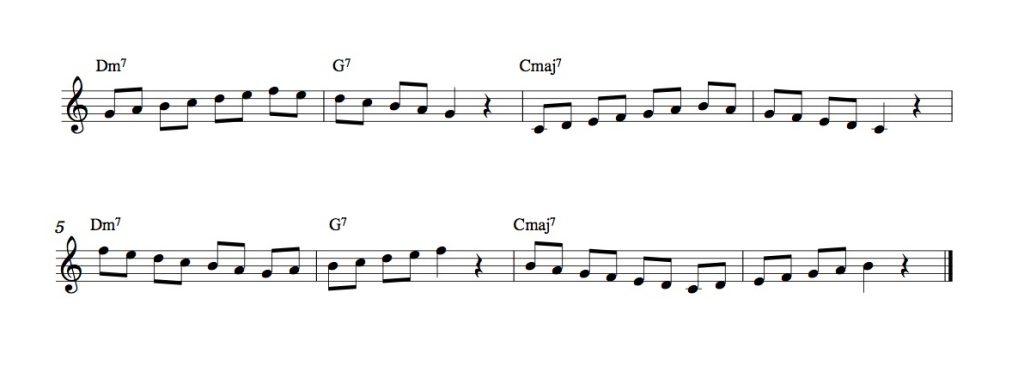

Along with learning a tune or pair of tunes in each group, determine where the ii-V, V-I and ii-V-I progressions are. For an explanation of the ii-V-I progression and one way of practicing ii-V-I voicings with RH major scales, see my blog post Join The ii-V-I Club.

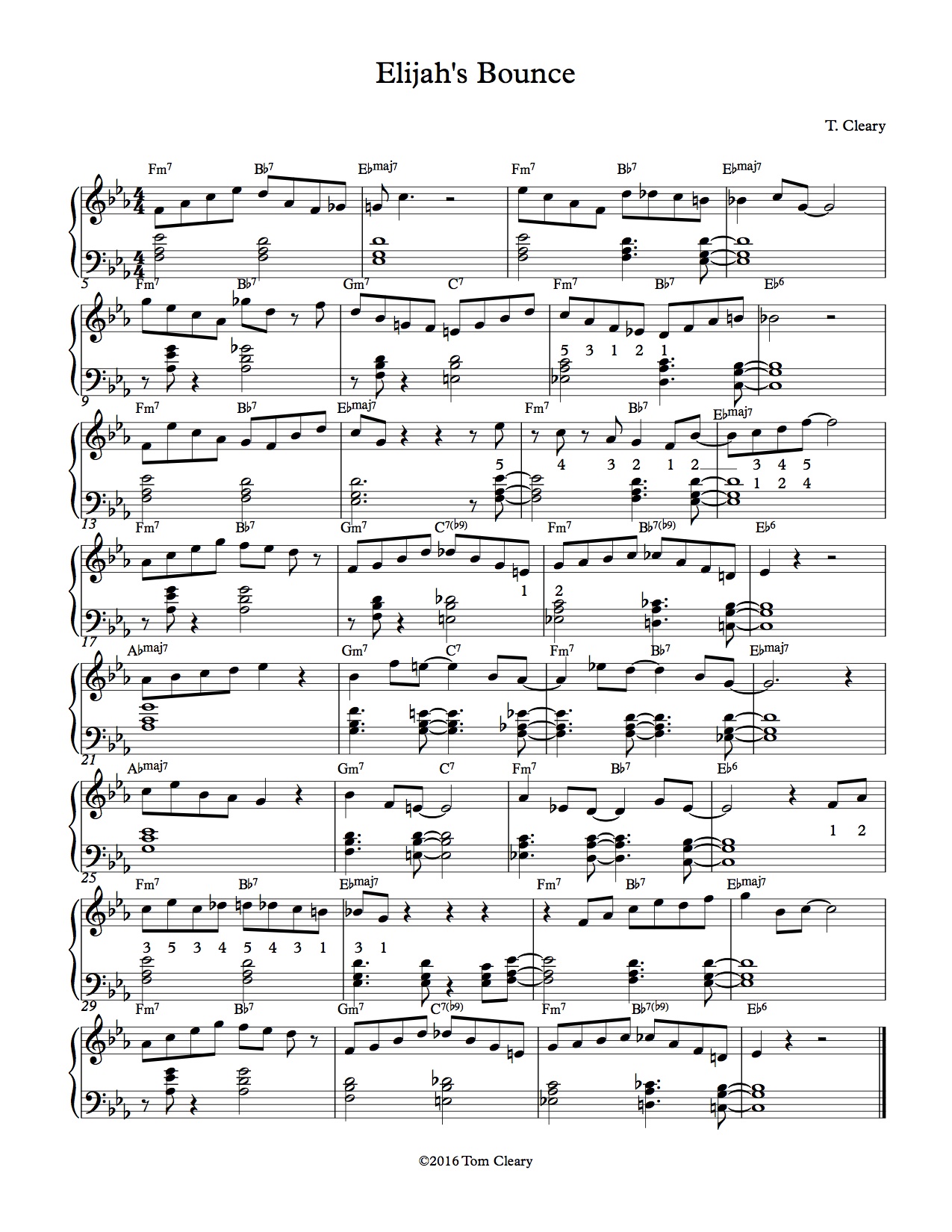

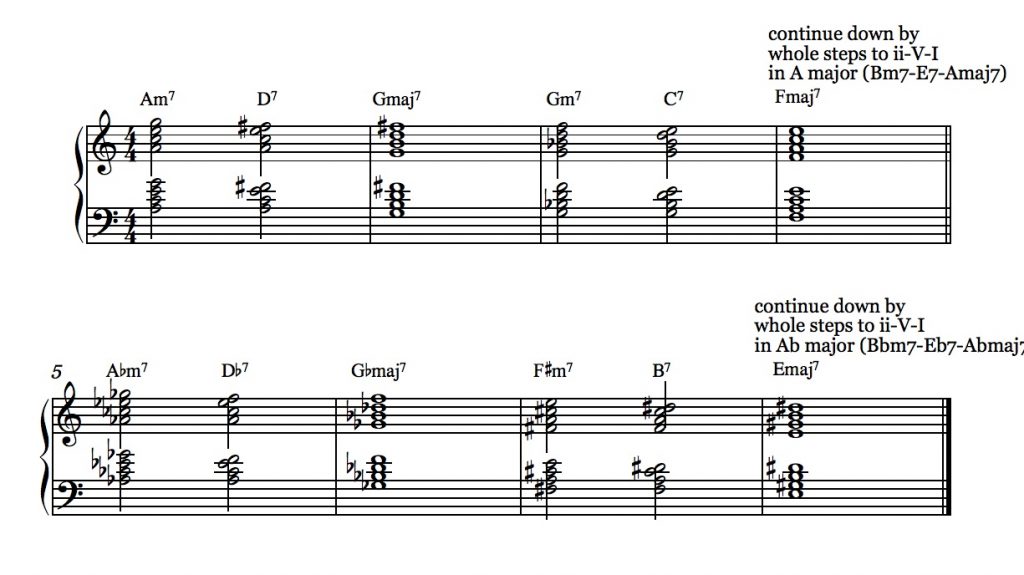

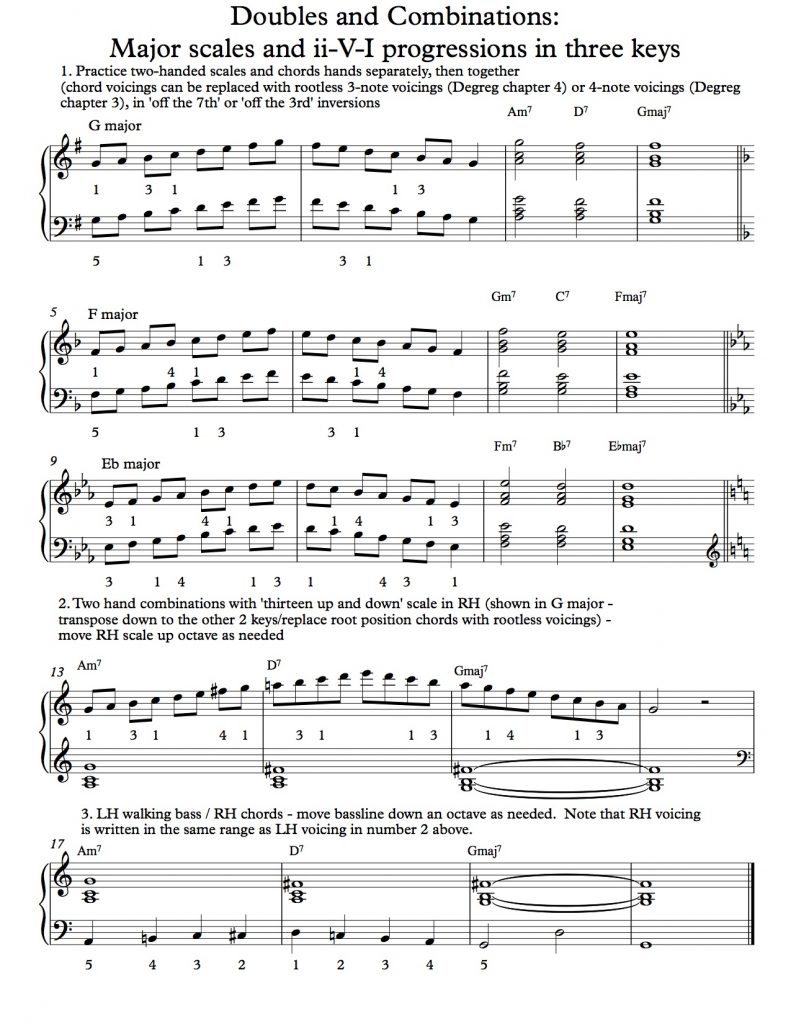

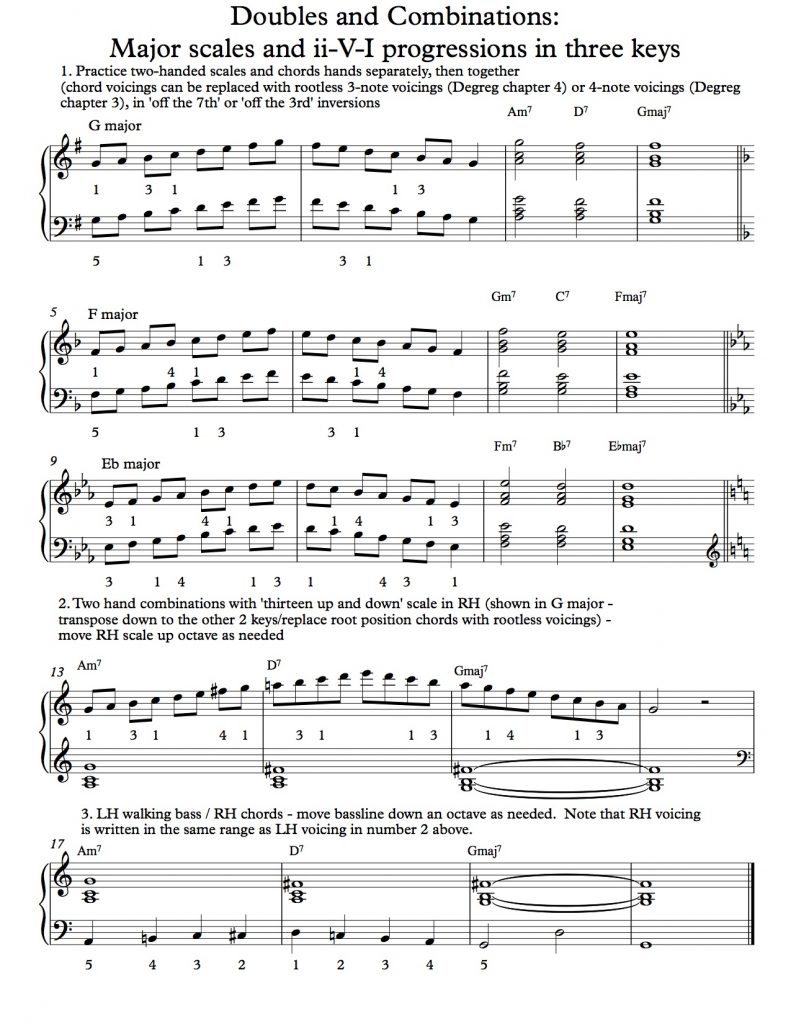

Another way of practicing scales and ii-V-I progressions is the ‘Doubles and Combinations’ exercise below. This exercise takes hands-together scales and chords and two handed combinations of chords and scales through a series of three keys descending by whole steps. The keys shown in this exercise are the major keys in How High The Moon. HHTM also includes G minor; to practice a and ii-V-i progression this key, flat the 3rd and 6th of the G major scale to make it the G harmonic minor scale, and flat the third of the Gmaj7 chord to make it a G minor seventh chord. (For Groups 2, 3 and 4 you will need to transpose the exercise below; for group 3, transpose a half step up; for Groups 2 and 4, transpose down to the keys indicated.)

Although root position voicings are useful for building basic knowledge of jazz harmony and making simple arrangements, and are used at times by a number of great players in jazz piano history, they can also (like the ‘blues scale’) become a trap if used exclusively. In addition to learning root position voicings for the ii-V-I progression in each key, it is also important to learn various rootless voicings for it in each key, particularly the most common which are sometimes referred to as ‘off the 7th’ and ‘off the 3rd’. More information on rootless voicings is available in my series of blog posts called ‘Harmonic Moss’, which starts with this post. There are a number of books which offer a ‘dictionary’ of rootless voicings; I most often use Jazz Keyboard Harmony by Phil deGreg as I find it has the most straightforward layout, but there are also similar and helpful books by Dan Haerle and Michele Weir.