(The title of this post is borrowed from a video narrated by U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a figure whose achievements in the political world have more than a few parallels to Camille Thurman’s achievements in the jazz world.)

Camille Thurman is a groundbreaking jazz musician in more ways than one. Along with a small number of younger players such as Bria Skonberg and Esperanza Spalding, she is reviving the tradition of the instrumentalist who is an equally adept and serious vocalist. Although this tradition goes at least as far back in jazz history as Louis Armstrong, it has always been somewhat rare and seems to have all but died out around the bebop era, when (at least according to most historical accounts) the chief innovations in the music were occurring in the instrumental world, leading the separation between instrumental and vocal jazz music to became even more pronounced than during the swing era. In an NPR interview, Thurman mentions she was shocked to discover that Sarah Vaughan’s considerable skills as a pianist remained a secret during most of her vocal career: “I remember when I first found out Sarah Vaughan was a pianist and it blew my mind away…I was like, ‘How can you just put one part of a person or an artist’s gift out there when there’s a whole person?” (Although Vaughan was originally hired as a second pianist in the Earl Hines big band, her piano skills stayed largely out of sight during most of her vocal career. It was only in her later years that she revealed her piano skills in live concerts such as this one and the Marian McPartland show which can be heard by clicking on Vaughan’s name above.)

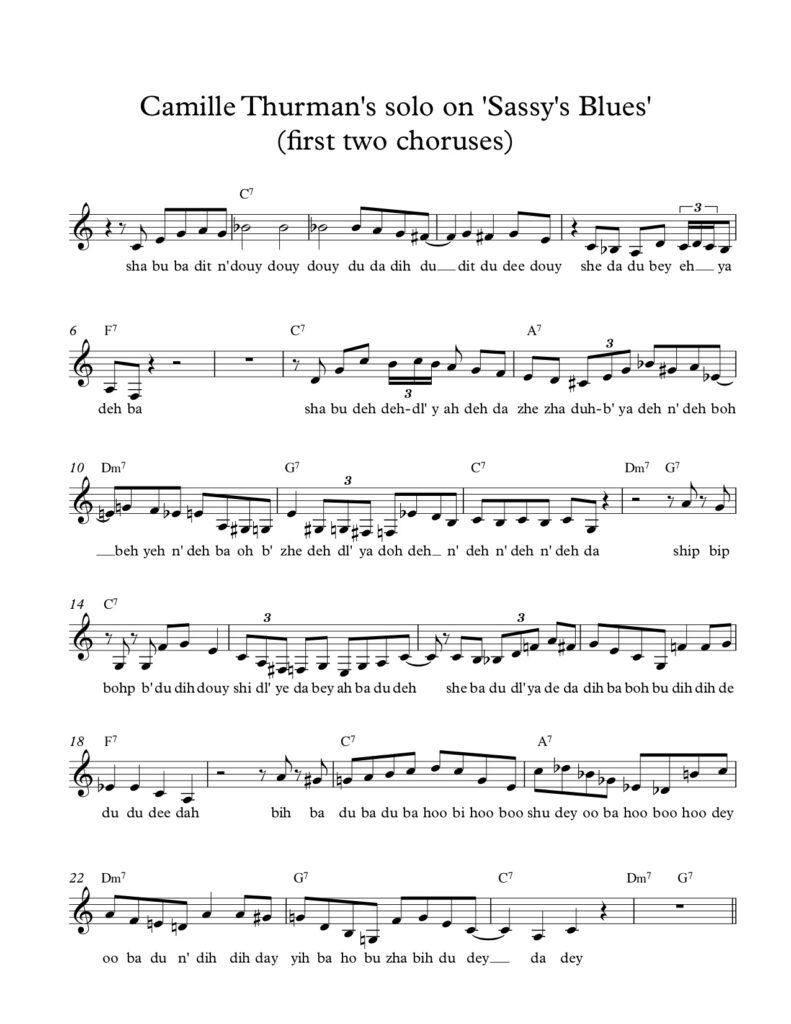

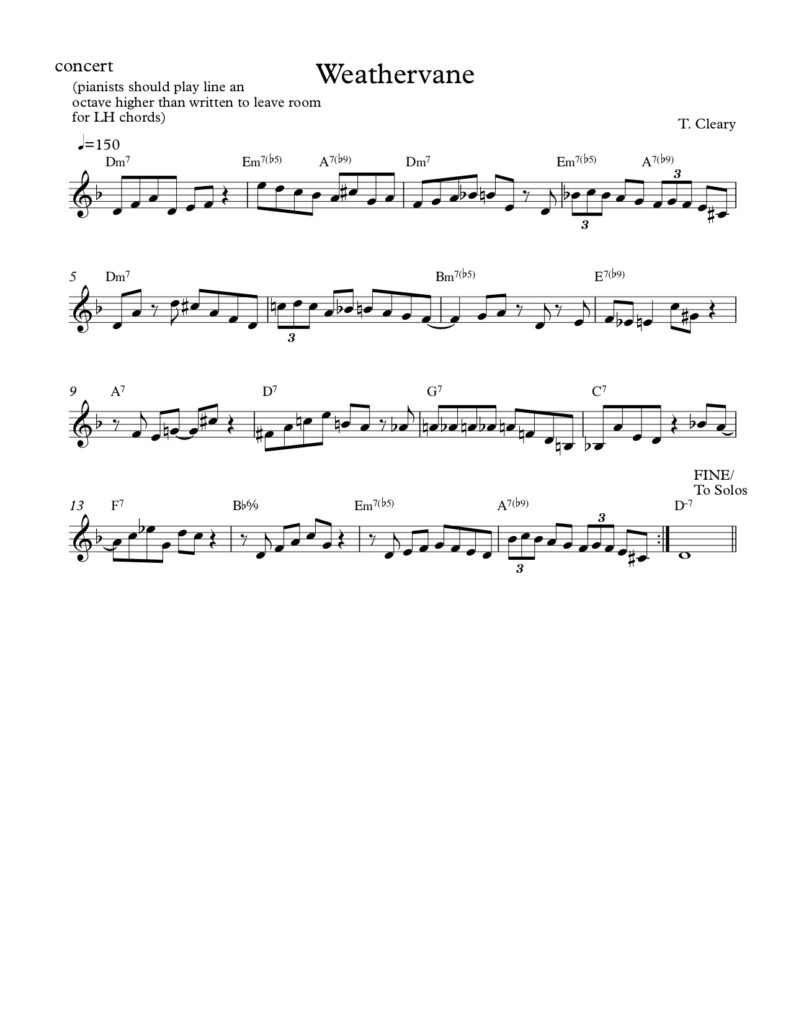

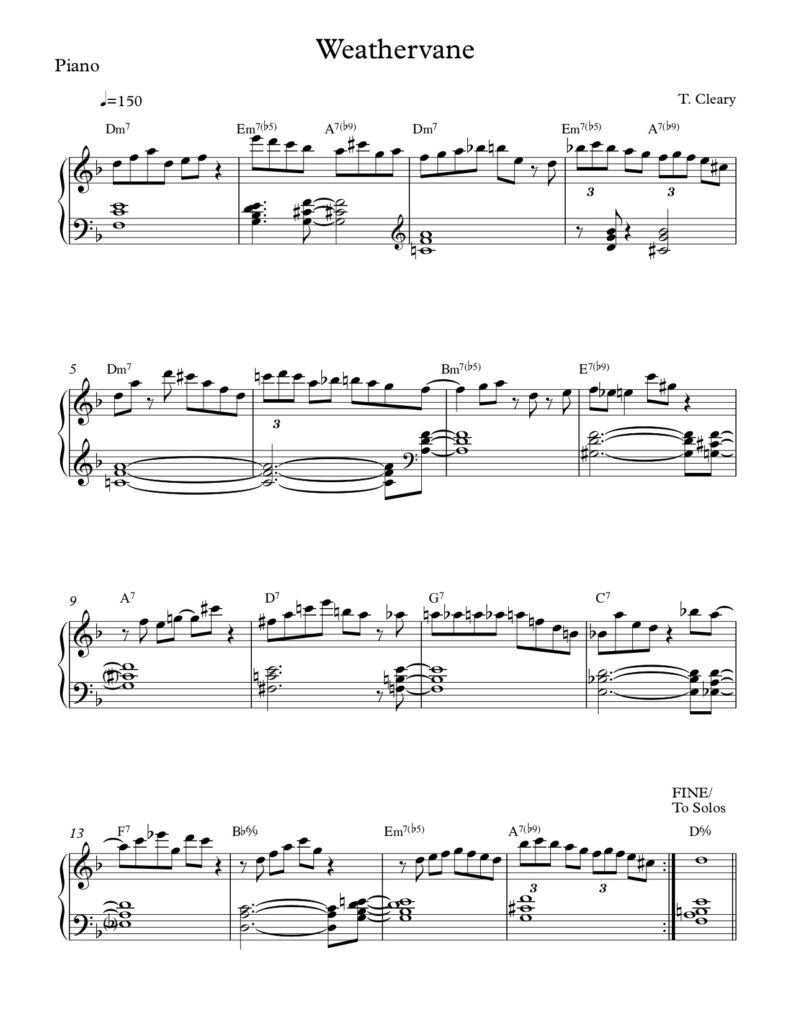

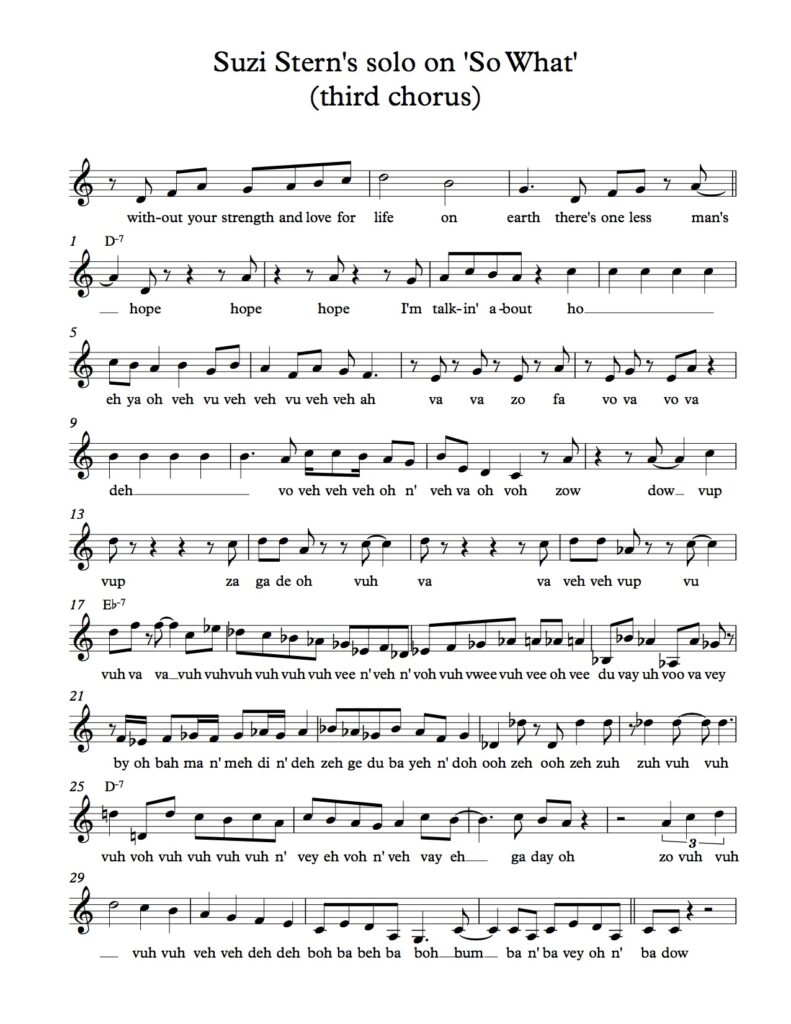

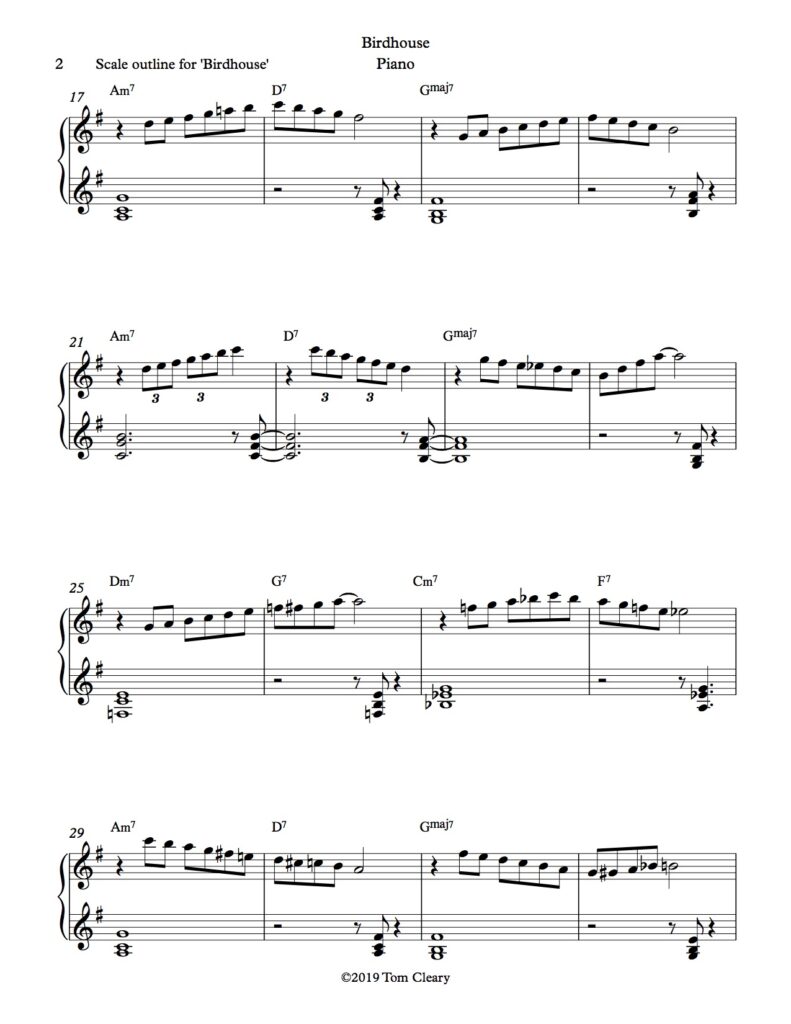

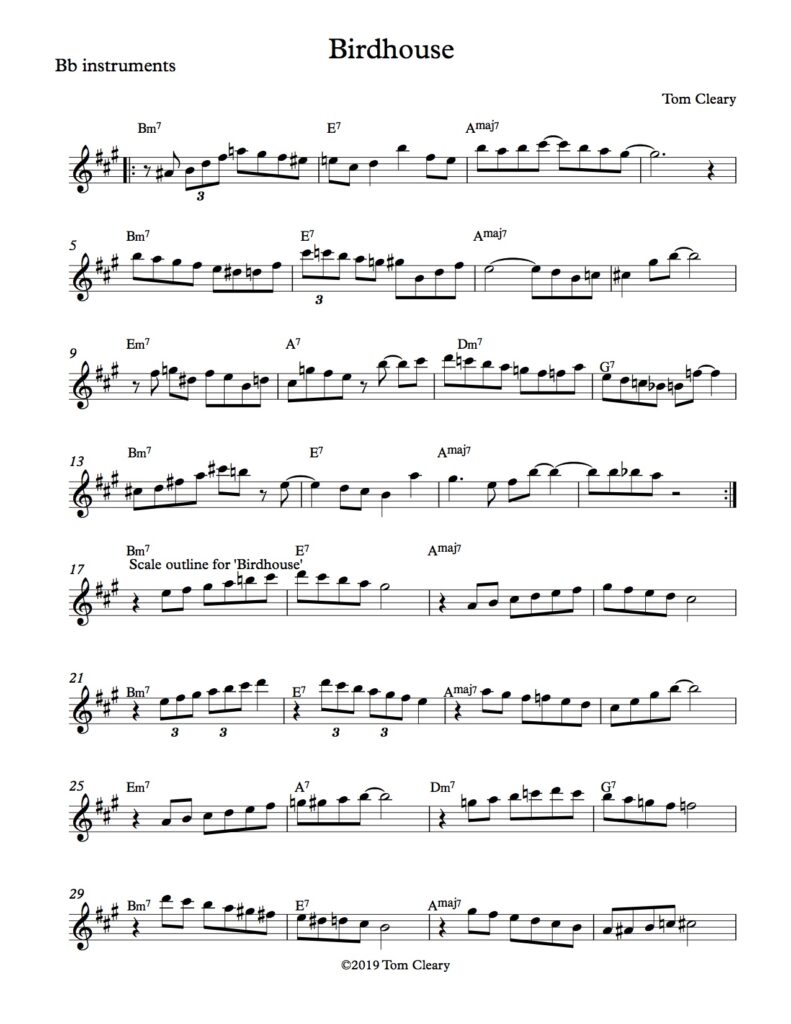

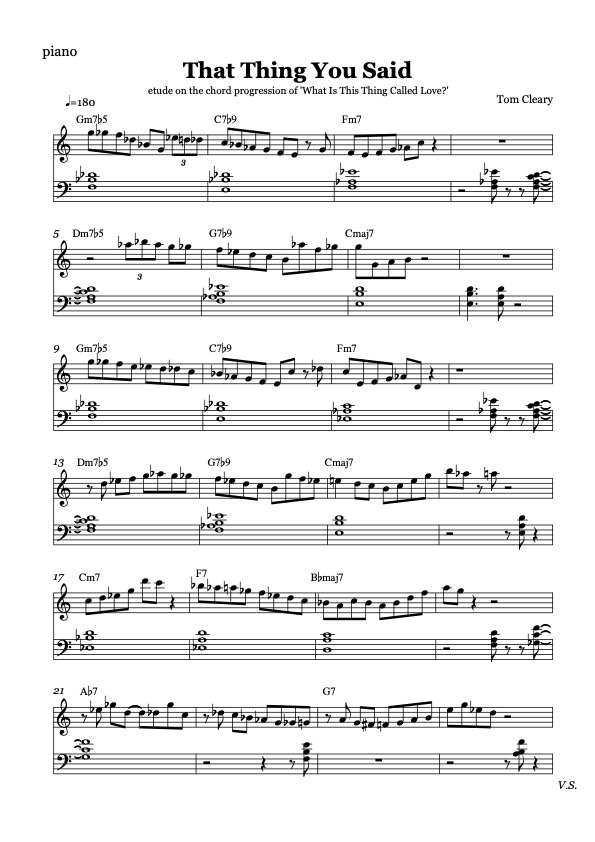

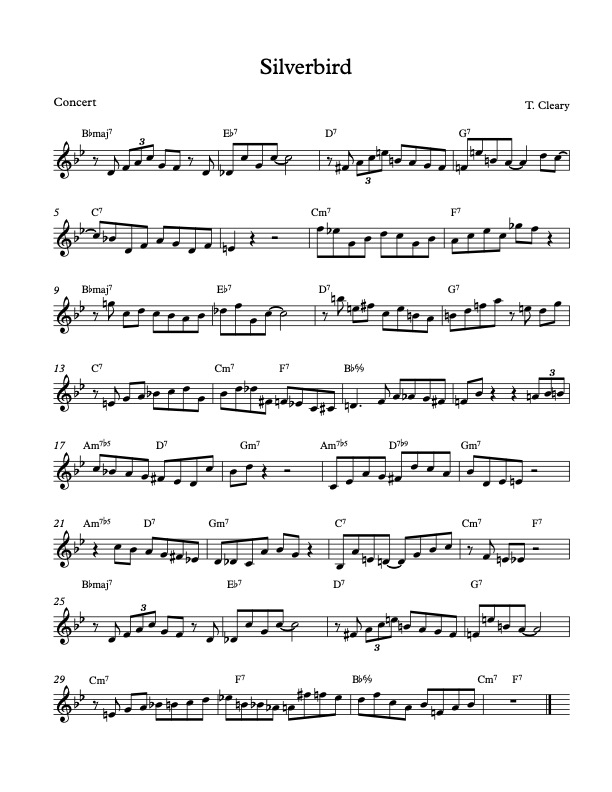

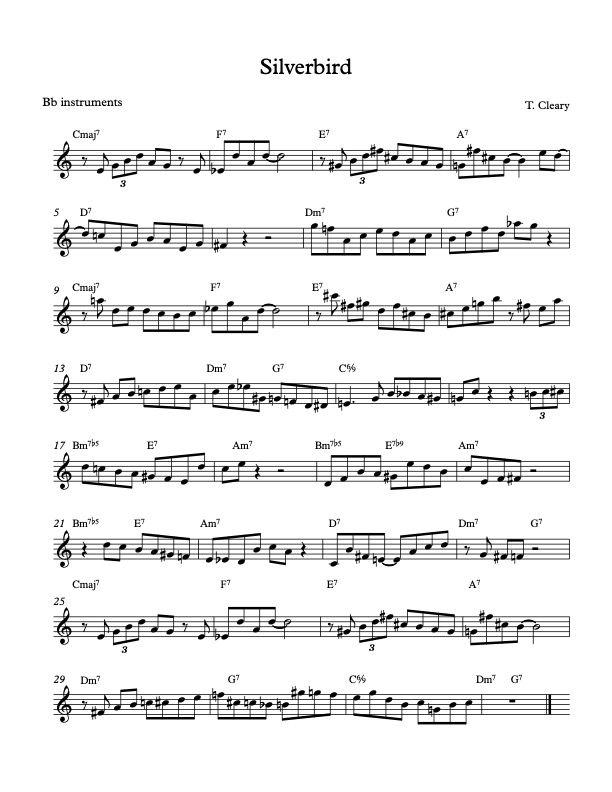

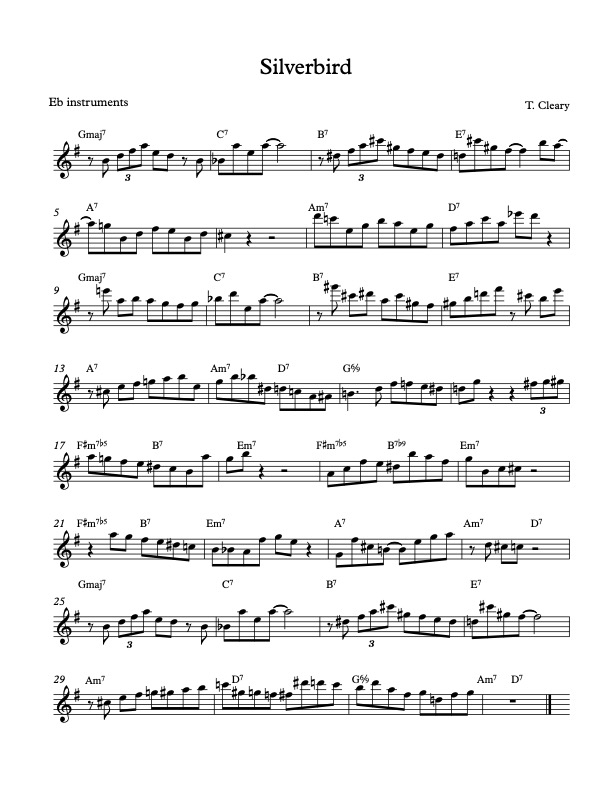

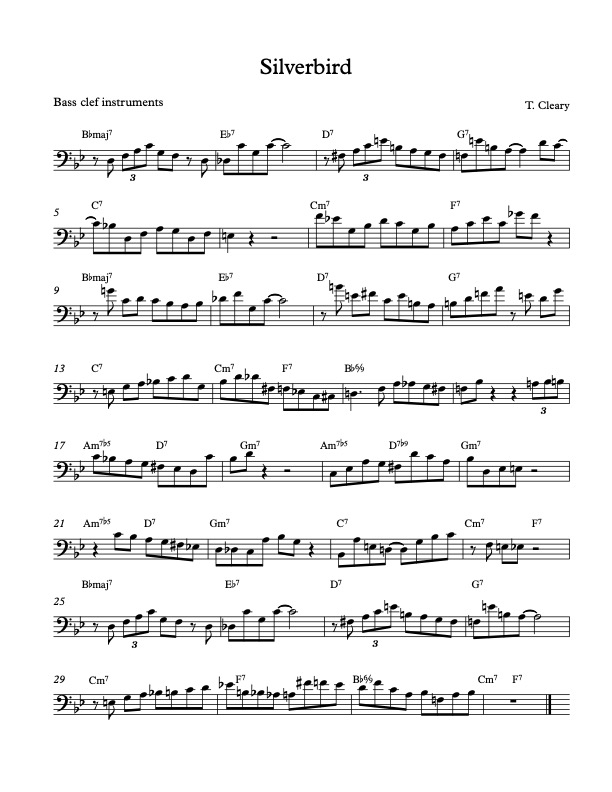

As one can see by listening to Thurman’s solo on ‘Sassy’s Blues’ from her album ‘Inside The Moment’ (my transcription of the first two choruses is posted below with her permission), she is a masterful improviser who demonstrates both a deep knowledge of jazz melodic language and the ability to make it her own. Her ability to begin phrases on the upbeat, as well as her ability to ‘make the changes’ in her solo locate her melodic language firmly within the bebop idiom. Her ability to lend an instrumental quality to her scatting and the range of syllables she chooses both give the solo a distinctly modern flair.

In the NPR interview I mentioned above, Thurman explains that while she has been singing informally since she was a child, she began to get more serious about singing when she found it a helpful way to learn saxophone parts (during a time in her life when she received a scholarship that required her to play the saxophone.) Each of her three albums gives a slightly different answer to the question of whether she identifies more as a vocalist or an instrumentalist; while ‘Origins’ and ‘Inside The Moment’ contain mostly instrumental pieces with the occasional vocal feature, last year’s ‘Waiting For The Sunrise’ highlights her singing on most tunes, although on many tracks Thurman alternates with seeming effortlessness between playing and singing. This remarkable feat, combined with the album’s ballad-heavy tune choices, makes it reminiscent of the classic ‘John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman’ album, but with the two masterful soloists rolled into one performer. (Perhaps the most succinct demonstration of Thurman’s ability to alternate between the two skills is an astonishing ‘There Will Never Be Another You’ from 2013.) I hope that Thurman might be a model for a new kind of jazz student, one who rejects the false choice between playing an instrument or singing and instead realizes that if one can develop both these skills, they can powerfully support and strengthen one another (regardless of whether or not one’s goal is to be a multi-instrumentalist.) I also hope that the increasing and increasingly visible ranks of professional female jazz instrumentalists, younger players such as Thurman, Spalding, Skonberg, Helen Sung, Linda May Han Oh and Tia Fuller as well as veterans such as Terri Lyne Carrington, Joanne Brackeen, and Jane Ira Bloom will lead aspiring female instrumentalists to stay in the game despite so many jazz scenes being male-dominated. The recently founded Women In Jazz Organization is also an important development in the jazz education scene. It is crucial that role models for female instrumentalists remain visible in the versions of the jazz world projected by the media and by educators because, as Marian Wright Edelman said, ‘It’s Hard To Be What You Can’t See.’ (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez gives her own version of this statement in the video mentioned above.)

Over the past year, Thurman has made a particularly momentous and groundbreaking move; she has been appearing regularly as a tenor saxophonist and vocalist with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, a group in which female instrumentalists have been historically and inexplicably absent from the roster of permanent players. As her website biography relates, she has become ‘the first woman in 30 years to work an entire season with the world-renowned orchestra (2018-2019).’ This careful wording manages to avoid mentioning that the group has never had a female player among its regular lineup. The group’s website mentions that it includes ‘15 of the finest soloists, ensemble players, and arrangers in jazz music today’, and many, myself included, would go further to say that it has been the leading jazz big band in the country since its inception. In its sense of prominence and mission, including its educational work in the Essentially Ellington competition, as well as a diplomatic functions representing the U.S. in performances around the world, the JALCO is a kind of jazz parallel to the U.S. Congress. As recently as last year, however, trumpeter Ellen Seeling, chair of the advocacy group Jazzwomen & Girls Advocates, was quoted as saying of the band that ‘“They travel the world and have for years, sending the message that there are no women good enough to be in this organization.” In light of the JALCO’s well-earned and deserved prominence, as well as the challenge it has had with including female musicians, Thurman’s breakthrough makes her a kind of jazz parallel to both Jeanette Rankin, the senate’s first female member, and Shirley Chisholm, its first African-American female member. (Strangely, despite having played more than a season at this point with the band, Thurman is still not listed on the JALCO website among either their regular members or on their list of substitute players.)

I am a longtime fan of the JALCO and its musical director, Wynton Marsalis. I have seen the full band twice in concert, seen Marsalis’ small group live, listened to them many more times on recordings, and have used the excellent scores from the Essentially Ellington competition with many student bands I’ve led. In an earlier blog post, I transcribed a characteristically ingenious solo Marsalis took on ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’ during his commencement speech at UVM in 2013. I’ve also experienced Marsalis’ legendary resistance to recognizing the talent of female instrumentalists firsthand. When a female student of mine asked him in a question and answer session at UVM around 2005 whether the quality of female jazz players in general was improving, his answer began with silent head-shaking, which was followed with a short verbal answer that boiled down to ‘No.’

In a Village Voice article published earlier in the decade, Marsalis’ response was somewhat more hopeful. The article, written in 2000 by Lara Paragrenelli, first acknowledges that ‘The Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra… has never had a female member’ and then goes on to quote Marsalis (I have included Paragrenelli’s interstitial comments as well): “ “I hire orchestra members on the basis of merit,” says artistic director Wynton Marsalis, implying women do not yet make the grade. “The more women we have playing jazz, the higher the level of playing gets, the more they audition, and the more women are going to be all over. It will be just like classical music.” Marsalis also cites slow turnover in the band of 15, limiting the availability of positions.” Paragrenelli goes on to quote historian Sherrie Tucker, author of Swing Shift: All-Girl Bands of the 1940s, who tells her that “The argument that women will eventually be good enough is very old.”

I have been thrilled and enlightened for many years by the sound of the JALCO’s performances, but in recent years I’ve increasingly noticed how it is full of age and culture diversity, symbolizes hope and excellence to many, and yet doesn’t include qualified women among its regular members, as one would expect from such a representative body. To have noticed this imbalance, and then to see the footage on Marsalis’ website of a performance including Thurman from earlier this year, alongside the National Symphony Orchestra of Romania, carries for me a taste of the thrill humans worldwide must have felt seeing Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon in 1969. The contrast between the Romanian group, which includes female players in every section, including multiple women among the woodwinds, and the JALCO with its single female member, dramatizes how the most recognized U.S. jazz group is just beginning to catch up to representative organizations in many fields in its gender diversity. Marsalis and the JALCO deserve long and loud accolades for finally recognizing in a prominent way the deep well of female instrumental jazz talent that has been in existence for many years. Here’s hoping that it is a sign of many more such changes yet to come.