A recent news story described how publishers who represent songwriters Jeff Lynne and Tom Petty contacted publishers for singer/songwriter Sam Smith about a four-bar similarity between the melody and chord progression of Lynne and Petty’s 1989 hit song ‘Won’t Back Down’ and Smith’s recent hit ‘Stay With Me’. Part of the settlement for this case was that in addition to receiving a financial settlement, Lynne and Petty will also be credited as co-composers of Smith’s tune. The stunned reaction of Smith and his collaborators, who said they were not familiar with Lynne and Petty’s tune and that the resemblance was ‘a complete coincidence’, is common among rock and pop songwriters who are informed about musical similarities between their work and previously copyrighted songs. In the classic case where the publishers of ‘He’s So Fine’ accused George Harrison of plagarizing their tune in his hit ‘My Sweet Lord’, a judge used the term ‘subconscious plagarism’ to describe Harrison’s process.

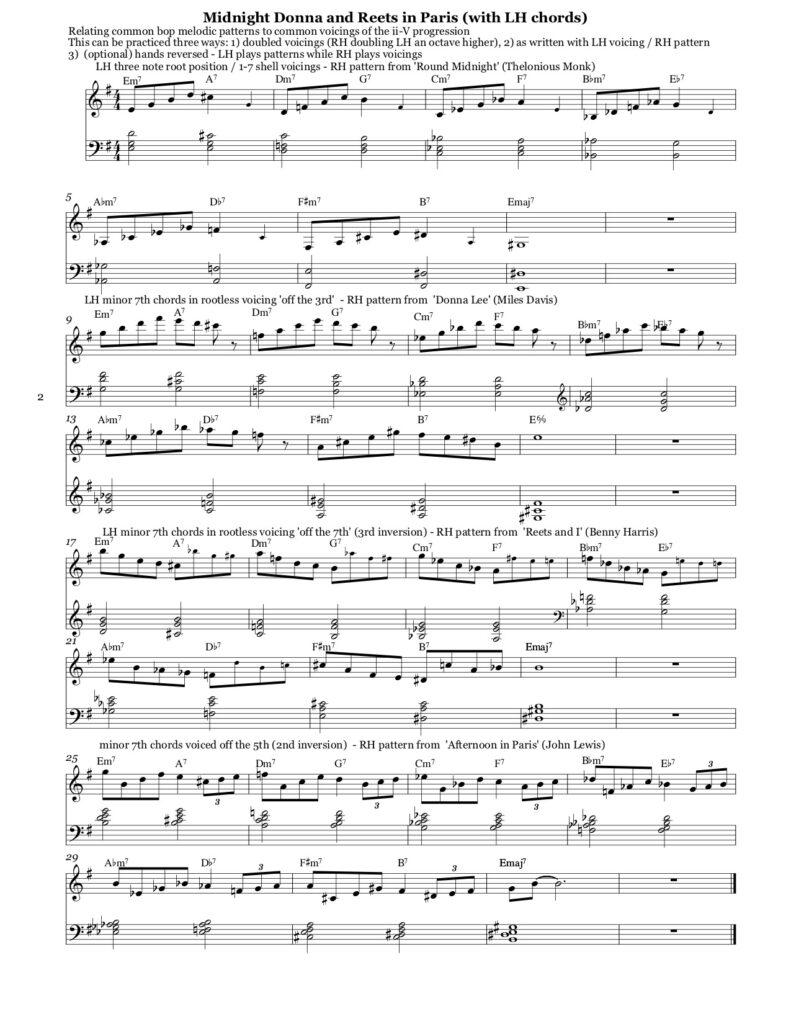

In the case of many classic tunes from the bebop era, the question of who composed them is still a subject of open debate, but musical analysis shows that they contain deliberate and artful borrowings from multiple sources. In many cases, such as ‘Donna Lee’, usually attributed to Charlie Parker but more recently claimed as the work of Miles Davis, the connections between tune and composer are enveloped in the mists of jazz history. This lack of certainty about composer credits has led many scholars of music from the bebop era to examine the tunes themselves for clues about their origin. In some research I did recently about the bebop anthem ‘Ornithology’, I found that the closer I looked, the more I heard the tune as being a musical collage that deliberately draws on multiple sources but is assembled artfully enough to sound like the work of a single hand.

In a recording from a live Boston concert in 1952, when a radio announcer asks Charlie Parker who composed ‘Ornithology’, he answers (along with the announcer) ‘Benny Harris’, without mentioning his own name. This answer, straight from Parker’s own mouth, contradicts a number of widely circulated published charts of ‘Ornithology’ which list Parker as the sole composer. After doing some historical research, I’ve concluded that it is most accurate to list Parker and Harris as co-composers (as a few published charts do), and that the sources of the tune likely extend beyond the two of them. While it has been well established that ‘Ornithology’ is based on the chord progression of ‘How High The Moon‘ by Morgan Lewis, the origins of the individual phrases in the tune are less often discussed. In the course of my research I looked at established theories on origins of phrases in ‘Ornithology’ and developed a few of my own. I also found that looking at relationships between ‘Ornithology’ and other tunes composed by Parker (or attributed to him) can highlight some general concepts that are helpful in the process of memorizing bebop tunes (and incorporating their concepts into one’s own improvisational vocabulary.)

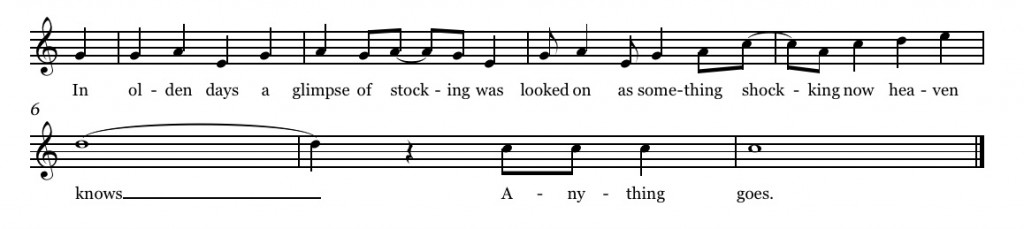

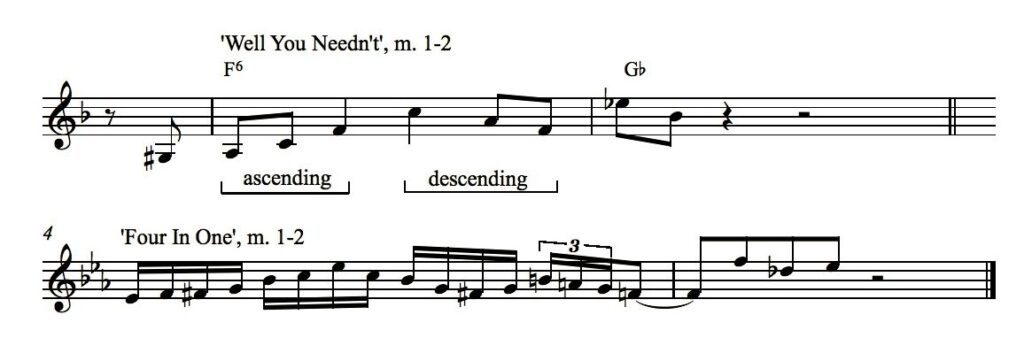

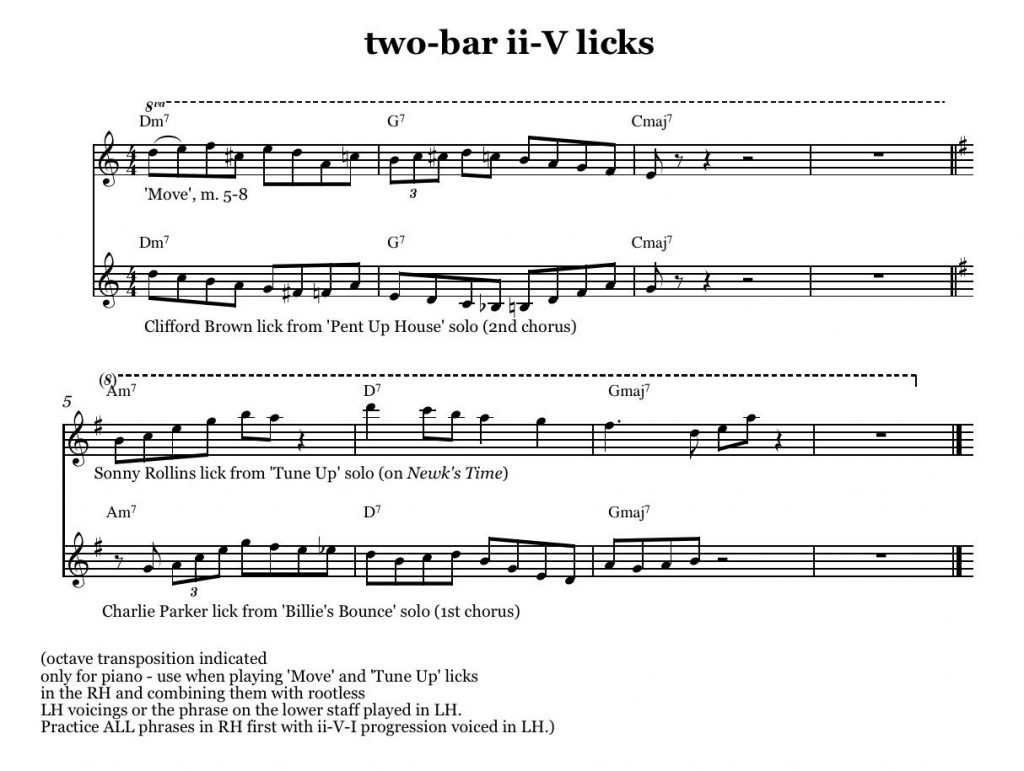

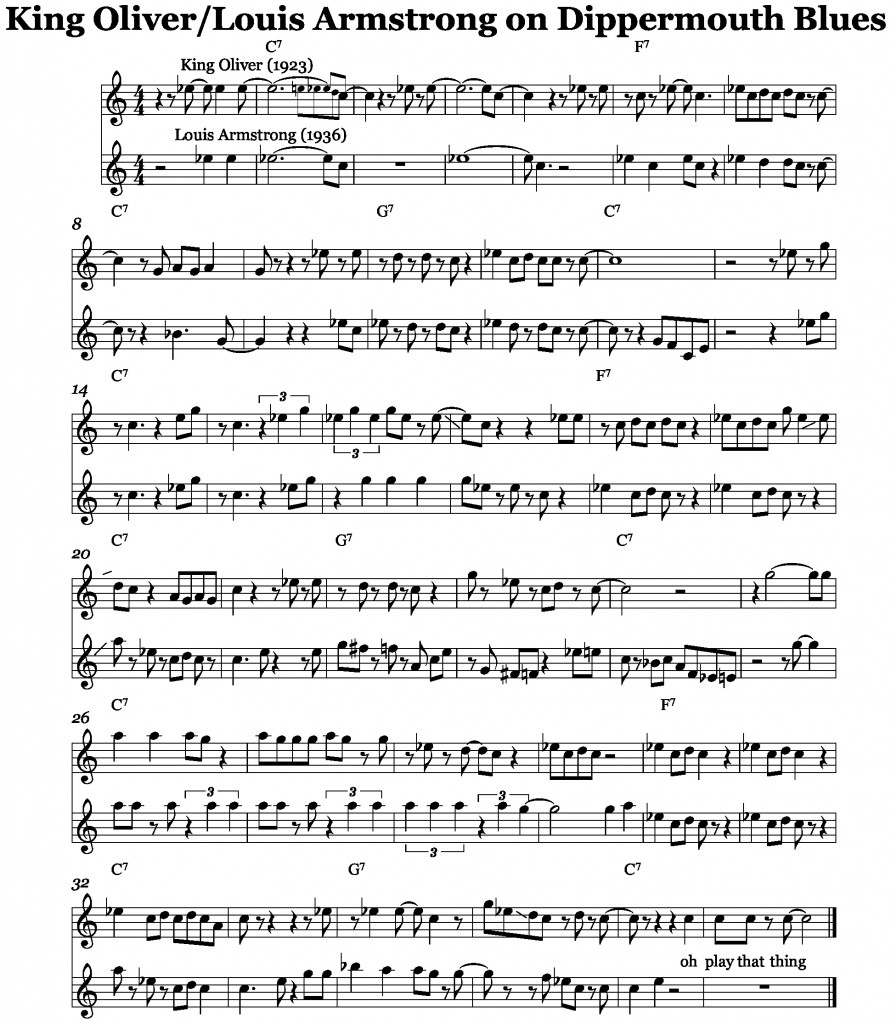

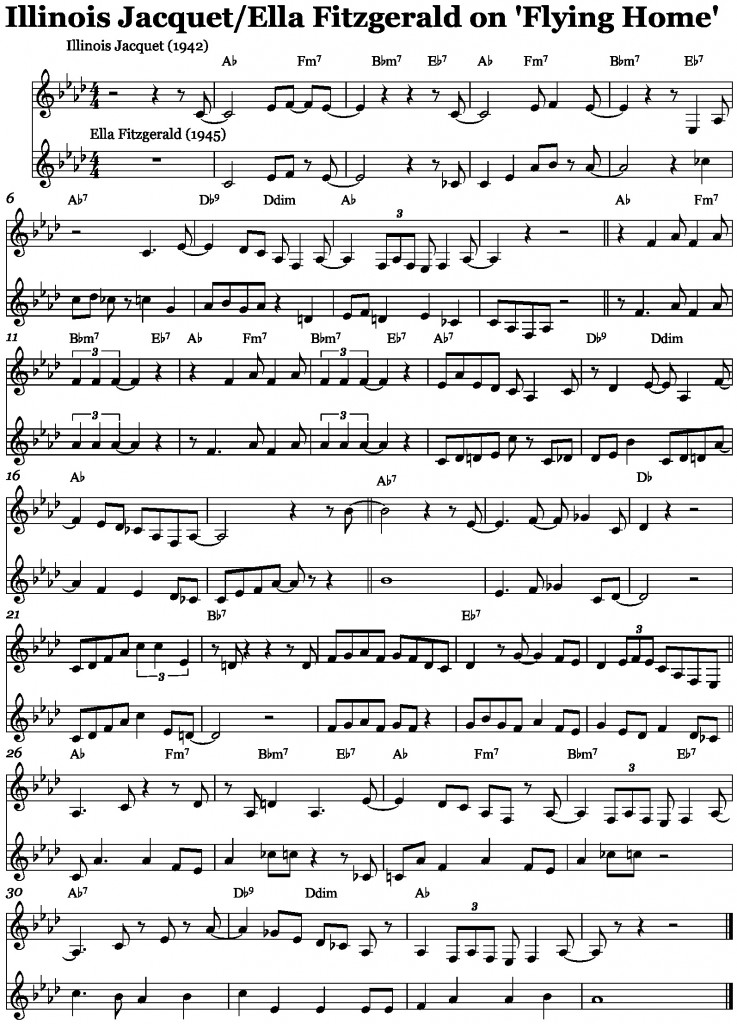

In his book Yardbird Suite, Lawrence Koch demonstrates that measures 1-2 of Ornithology were taken by Benny Harris from the opening of Parker’s solo on the 1942 recording of ‘The Jumpin’ Blues’ by the Jay McShann Orchestra. Right off the bat, the first phrase of this seminal bebop tune shows the crucial process of extracting licks from great solos and transposing them to other keys, as it transposes the lick from ‘The Jumpin’ Blues’ from its original E flat to G major, the key of ‘How High the Moon’:

Measures 3-4 of ‘Ornithology’ show Harris engaging with another process essential to the improviser: altering or developing a learned melodic idea to adapt to a different harmonic context (in this case, a different chord progression.) In this case Harris adapts Parker’s idea in a way that fits the move to the parallel minor in m.3 of the progression to ‘How High The Moon’.

(A more recent example of this can be heard in a recording of ‘Anthropology’ by Parker’s friend Sheila Jordan. In her solo, Jordan takes a phrase from Benny Harris’ tune ‘Reets and I’, a tune based on ‘All God’s Children Got Rhythm’, and develops it in a way that fits the progression of ‘Anthropology’.)

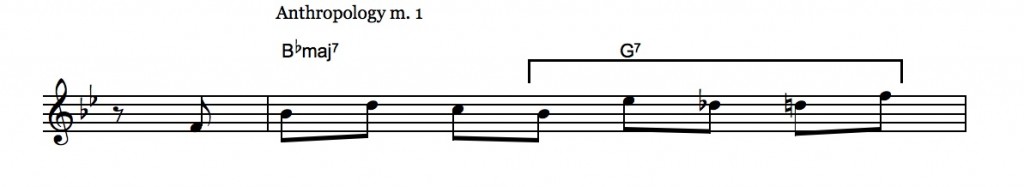

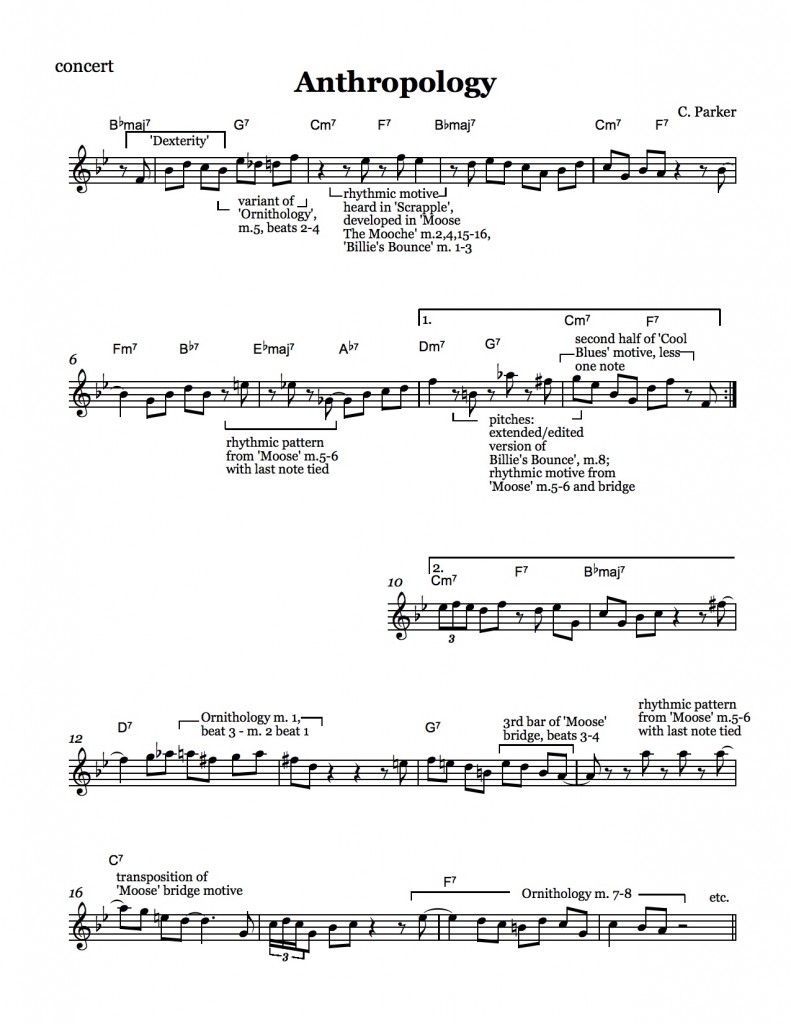

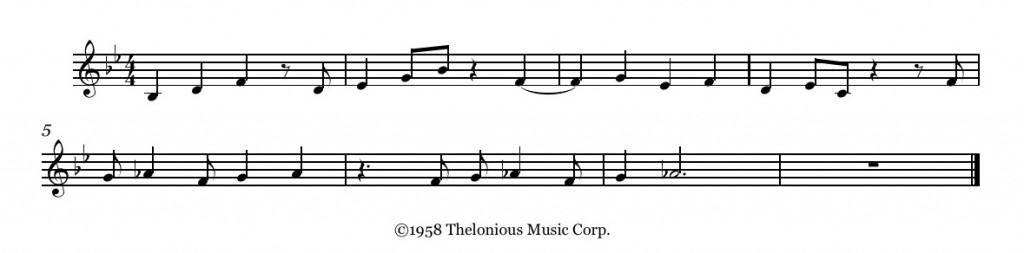

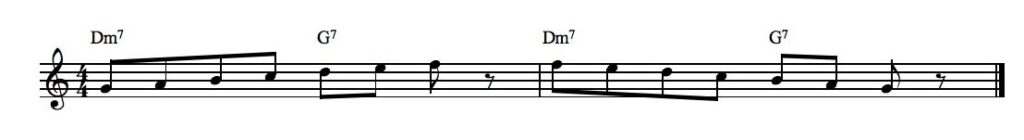

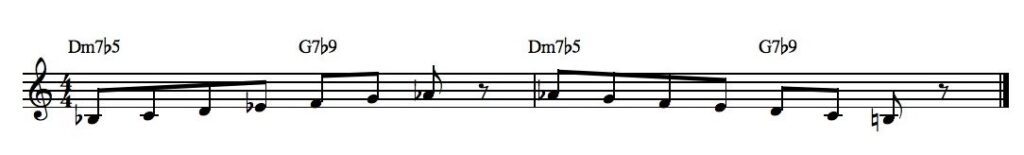

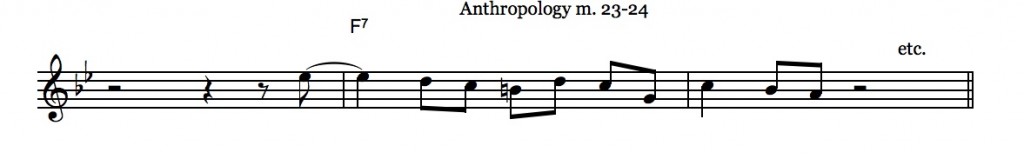

I have noticed that the last five notes of measures 5-6 are a motive which Parker uses with a one-note alteration in the opening of ‘Anthropology’:

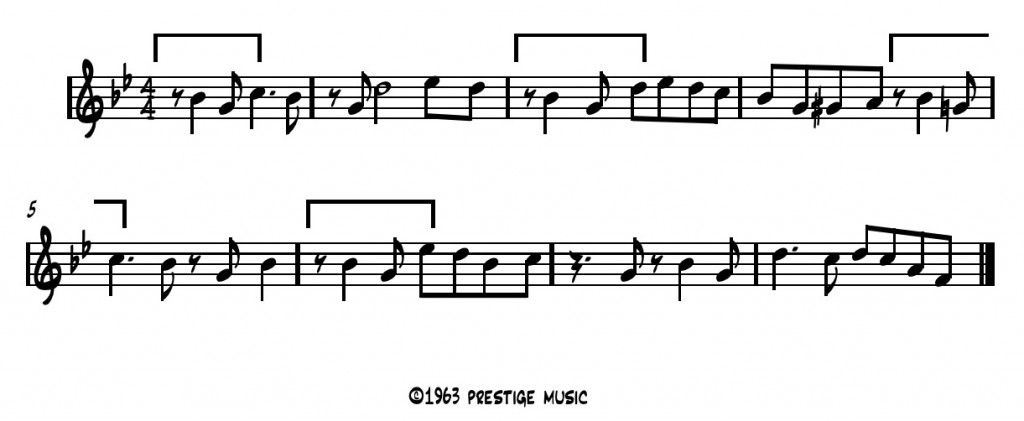

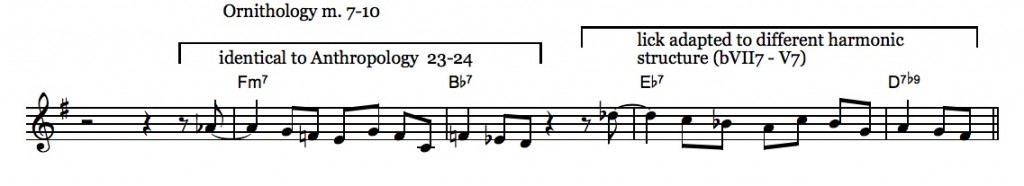

David Baker is among those who have pointed out that the motive used in measures 7-8 in ‘Ornithology’ is the same figure seen the last two measures of the bridge of ‘Anthropology’ (although, as with the ‘Jumpin’ Blues’ lick, Harris had to transpose the lick to make it work in ‘Ornithology’.) (Measures 9-10, like measures 3-4, adapt the borrowed lick to a different set of chord changes than those with which it originally appeared.):

Of these two tunes, ‘Anthropology’ was recorded first, and given the many stories of Parker composing tunes shortly before they were recorded (or even the same day), it would suggest that Benny Harris took these from ‘Anthropology’ and used them in ‘Ornithology’. Given the competing historical accounts of when Parker tunes originated, there is no way to be sure of this theory, but in any case, noticing similarities between two tunes makes it easier to learn both of them.

Of these two tunes, ‘Anthropology’ was recorded first, and given the many stories of Parker composing tunes shortly before they were recorded (or even the same day), it would suggest that Benny Harris took these from ‘Anthropology’ and used them in ‘Ornithology’. Given the competing historical accounts of when Parker tunes originated, there is no way to be sure of this theory, but in any case, noticing similarities between two tunes makes it easier to learn both of them.

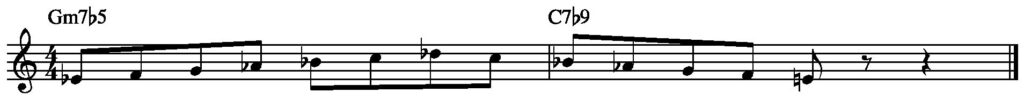

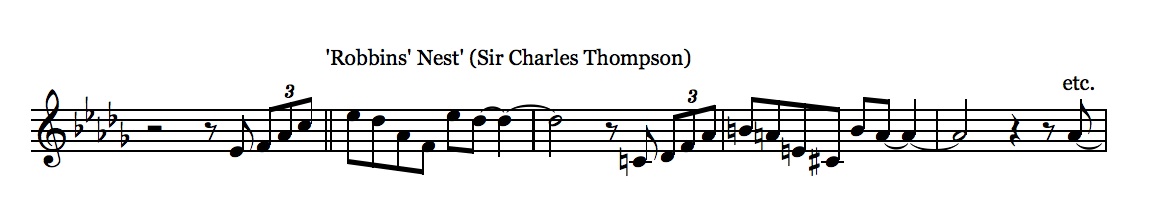

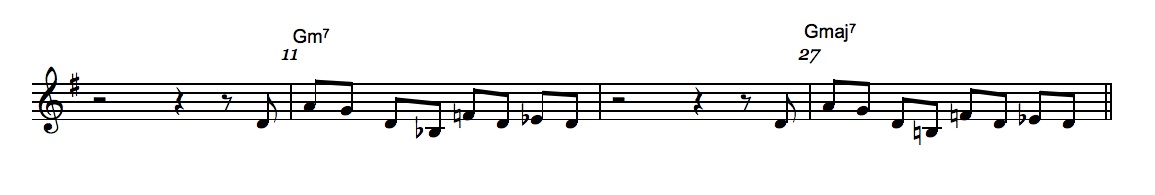

I think it is possible that measures 11-12 show a knowledge of Parker’s career that goes beyond a familiarity with his licks to a detailed knowledge of his playing career. These measures bear a strong resemblance to the main motive of ‘Robbins’ Nest’, a tune composed by Sir Charles Thompson, a pianist and bandleader with whom Parker worked a number of times. (The link above is to a 1990s recording of the tune by the composer; there is also a great version by Milt Buckner which demonstrates his mastery of ‘locked-hands’ technique, a technique which by some accounts he originated, although it is commonly associated with George Shearing.) Although Parker’s one recording session with Thompson did not include ‘Robbins’ Nest’, it is likely that he would have played it in the course of his work with Thompson, as it was one of the bandleader’s best known tunes. In a reversal of measures 1-4 and 7-10, where a lick is first stated in a way that exactly matches its appearance in another context and is then followed by a transformation, the ‘Robbins’ Nest’ theme is used first with a minor key alteration in m. 11-12 and is then returned to its original major-key context in measures 27-28. (The minor-key alteration of the ‘Robbins’ Nest’ motive in m. 11 also matches the first four notes of the jazz standard ‘Cry Me A River’, which as Greg Fishman demonstrates is the source of a frequently used and multipurpose lick.)

(The link above is to a 1990s recording of the tune by the composer; there is also a great version by Milt Buckner which demonstrates his mastery of ‘locked-hands’ technique, a technique which by some accounts he originated, although it is commonly associated with George Shearing.) Although Parker’s one recording session with Thompson did not include ‘Robbins’ Nest’, it is likely that he would have played it in the course of his work with Thompson, as it was one of the bandleader’s best known tunes. In a reversal of measures 1-4 and 7-10, where a lick is first stated in a way that exactly matches its appearance in another context and is then followed by a transformation, the ‘Robbins’ Nest’ theme is used first with a minor key alteration in m. 11-12 and is then returned to its original major-key context in measures 27-28. (The minor-key alteration of the ‘Robbins’ Nest’ motive in m. 11 also matches the first four notes of the jazz standard ‘Cry Me A River’, which as Greg Fishman demonstrates is the source of a frequently used and multipurpose lick.)  If, as seems likely to me, these two phrases are references to the Thompson tune, ‘Ornithology‘ begins to look like a highly detailed (one might even say ‘nerdy’) tribute to Parker that references three stages of his career: his early work with the Kansas City pianist Jay McShann in m. 1-4, and his collaboration with by Dizzy Gillespie (who some scholars think had a hand in the composition of ‘Anthropology’) in m. 5-10, and his work in Washington D.C. and later in New York with Charles Thompson in m. 11 and 27. One could use this non-linear tour of Parker’s mid-life career as a structure for remembering the tune (in a process akin to the ‘memory palace’ technique demonstrated in the PBS series Sherlock.)

If, as seems likely to me, these two phrases are references to the Thompson tune, ‘Ornithology‘ begins to look like a highly detailed (one might even say ‘nerdy’) tribute to Parker that references three stages of his career: his early work with the Kansas City pianist Jay McShann in m. 1-4, and his collaboration with by Dizzy Gillespie (who some scholars think had a hand in the composition of ‘Anthropology’) in m. 5-10, and his work in Washington D.C. and later in New York with Charles Thompson in m. 11 and 27. One could use this non-linear tour of Parker’s mid-life career as a structure for remembering the tune (in a process akin to the ‘memory palace’ technique demonstrated in the PBS series Sherlock.)

If Harris is the primary composer of the tune, as Parker’s answer from the 1952 radio broadcast indicates, it starts to look like a piece of what today in popular literature is called ‘fan fiction’ – creative works in which themes or characters created by a famous author are developed by a lesser-known but nonetheless skilled admirer of the famous author’s work. While Harris was in many ways a contemporary of Parker’s, and so was well qualified to create an anthology of his licks, the fact that he was more known as a sectional player than as a soloist also suggests that, in addition to being an associate of Parker’s in groups such the Earl Hines and Dizzy Gillespie big bands, he was enough of a ‘fan’ to pull those licks from a variety of different eras in Parker’s career. The pun in Harris’ title of the tune (i.e. taking a word that means the study of birds and using it to reference to the study of ‘Bird’) refers not just to his own study of Parker, but to a musically astute subset of Parker’s fans who were devoted to preserving and studying his improvisations, such as Dean Benedetti, whose live recordings of Parker were released in the late 1980s.

There are two different versions of the melody in measures 13-16; in the first recorded version of the tune, a triplet lick is passed between the trumpet, alto, tenor and guitar during these measures. In later versions of the tune, such as the one on ‘One Night In Birdland’, these measures are replaced with a phrase which is melodically similar to the bridge of ‘A Night In Tunisia’ and rhythmically similar to the bridge of ‘Moose The Mooche’. The distinctiveness of the rhythmic motive, which also shows up in the bridge of ‘Anthropology’ and the fourth measure of ‘Scrapple From The Apple’, suggests that this might be an addition by Parker and not part of Harris’ original assembly of Parker licks. When this revision is added to the tune, it makes it much more sensible as a feature for a soloist, as the original version requires an antiphonal exchange between instruments. (The revision also made practical sense for Parker, as live recordings of the tune demonstrate that he often played the tune on pick-up gigs with local rhythm sections, and would likely have not had the time to rehearse the original version with these groups.)

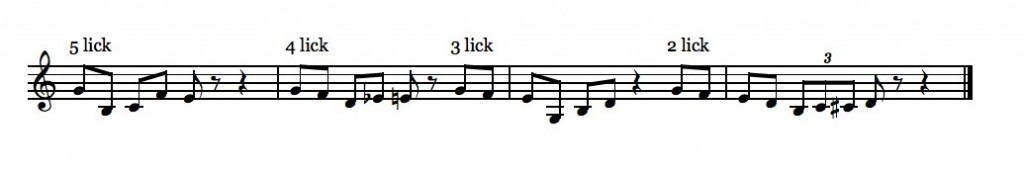

Looking at the relationships between ‘Ornithology’ and other Parker tunes is a reminder of some of the main characteristics of bebop melodic concepts (i.e. licks):

– They are often built in two measure phrases; even phrases that sound like longer melodic units are built from two measure components.

– Many phrases begin on upbeats, and phrases that begin single upbeats are often contrasted with phrases that begin with multiple upbeats.

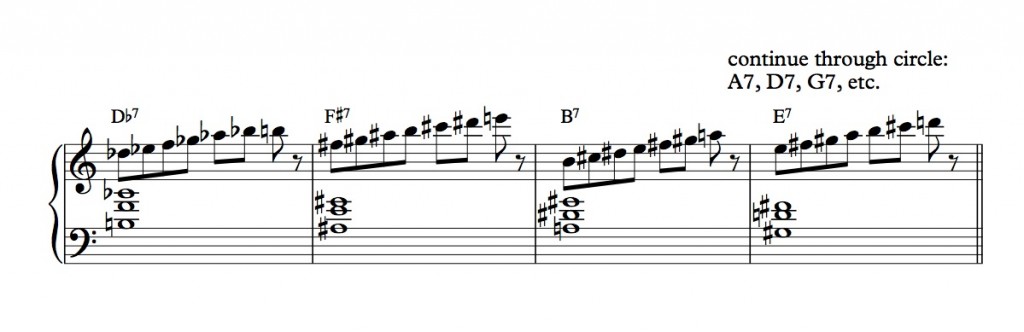

It is helpful to know the source of a lick, or at least identify it with first tune in which one encountered it, and identify it when it recurs in other contexts. Some examples:

– the ‘Jumpin Blues’ lick, which is re-used by Harris in ‘Ornithology’, is also re-used in Clark Terry and Jimmy Hamilton’s ‘Perdido Line’ and number of Ella Fitzgerald’s solos on ‘How High the Moon’.

– the ‘Cool Blues’ lick (from the riff blues of the same name), an altered fragment of which appears in m. 8 of Anthropology, is used in the Parker solos on Yardbird Suite and Dewey Square which appear in the Charlie Parker Omnibook.

– the ‘Honeysuckle Rose’ lick (from the opening of the Fats Waller tune by the same name) shows up in m. 8 of ‘Blues for Alice’ (rhythmically altered and with one note subtracted), in m. 15 of Donna Lee, and Parker disciple Cannonball Adderley’s solo on the Bobby Timmons tune ‘This Here’ (he uses the lick around 3:00, with two notes reversed.)

– while the second half of the ‘Robbins’ Nest lick’ is used in m. 11 and 27 of Ornithology, the opening of the lick can be heard in the bridge of Parker’s ‘Dewey Square’ solo.

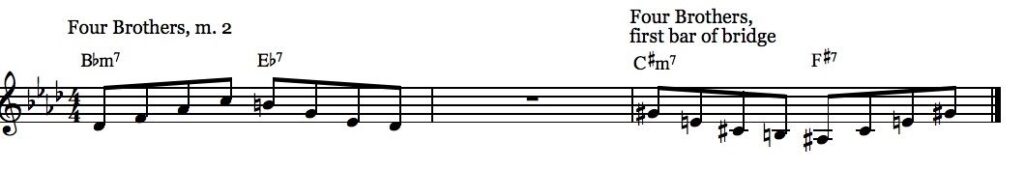

– The lick from m. 5 of Anthropology was re-used by Parker in a rhythmically altered version in the last measure of Confirmation. Measure 2 of Sonny Rollins’ ‘Doxy’ closely follows both the melodic and rhythmic pattern of the ‘Confirmation’ ending but ends on the 6th rather than the root. The theory that this phrase was borrowed from ‘Confirmation’ is supported by the fact that Rollins was a student of Parker’s melodic language. However, Rollins is also a master of motivic development, both in his improvising and his compositions, and this makes it just as likely that m.2 of ‘Doxy‘ is an inversion (i.e. upside-down version) of the first measure of the tune.

Parker’s ability to use a single lick in multiple contexts, and to succeed so often at making it part of a coherent whole with its own structural integrity, was one of the factors that led to his creating such a uniquely memorable body of improvised work. In his Parker biography Chasin’ The Bird, Brian Priestly writes that some of Parker’s ‘improvisations on standards…were so popular that audiences could sing along with his recorded improvisation.’ But as with the work of Beethoven, the strength of the whole in Parker’s work derives in part from the strength of the motives he chose to use, and those motives have since been identified and catalogued by scholars including Lawrence Koch in his aforementioned book.

Some accounts of Parker’s life indicate that, although he did not musically notate his vocabulary of licks or catalogue them in a formal sense, he did sometimes associate certain licks with symbolic meanings. Priestly quotes bassist and Parker collaborator Gene Ramey as saying of Parker: ‘Everything had a musical significance for him. He’d hear dogs barking, for instance, and he would say it was a conversation – and if he was blowing his horn he would have something to play that would portray that thought to us. When we were riding the car between jobs we might pass down a country lane and see the trees and some leaves, and he’d have some sound for that. And maybe some girl would walk past on the dance floor while he was playing, and something she might have would give him an idea for something to play in his solo. As soon as he would do that, we were all so close we’d all understand just what he meant.’

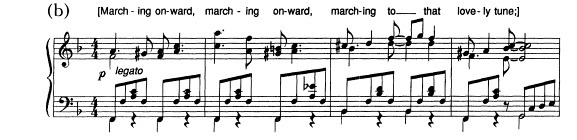

Some recent episodes of the radio show and podcast Birdnote describe how this symbolic use of musical phrases occurs in the world of actual birds as well. The black-capped chickadee uses different variations on its main call to scold predators and announce food sources, and a markedly different call to seek a mate in the spring. Wood-wrens use a series of quickly alternating call-and-response phrases which ornithologists believe ‘reinforces pair bonds in birds that frequently lose sight of each other’. (One of the wrens’ phrases turns out to be an ornamented version of ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’.)

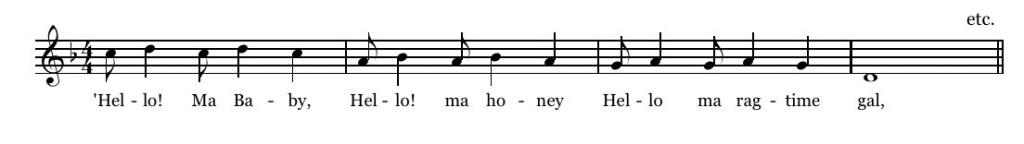

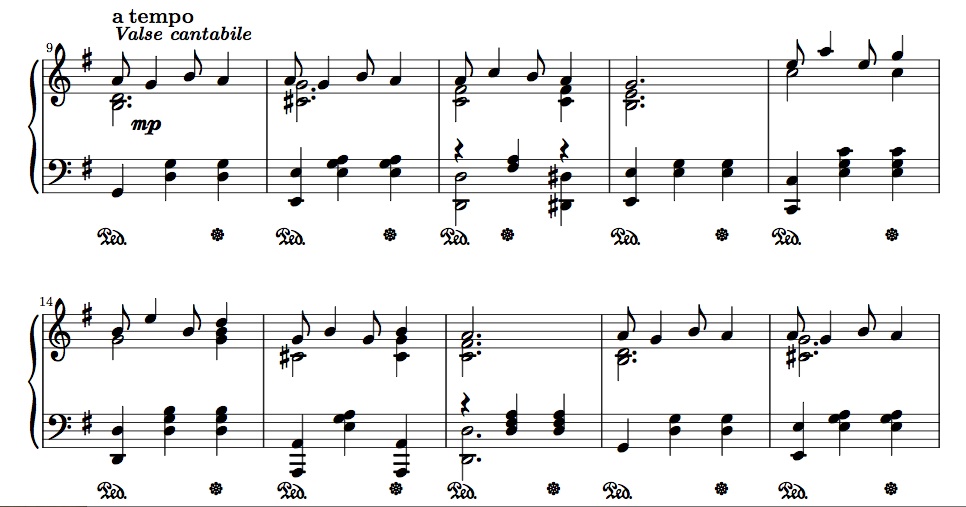

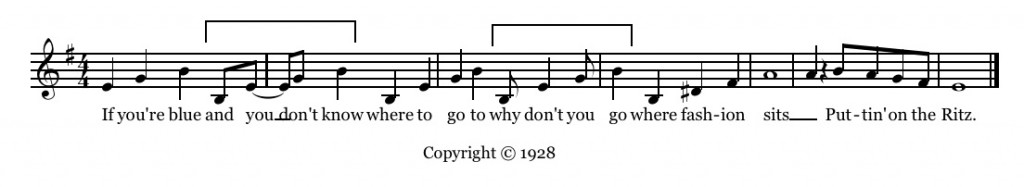

Naming melodic phrases based on their origin, or the context in which one initially discovered them, or a symbolic association can be a helpful ‘hook’ on which to ‘hang’ one’s memory of the melody. If one can attach these hooks to the framework of the chord progression, it further stabilizes the tune in one’s memory. With Sonny Rollins’ tune ‘Doxy’, for example, if I remember that the chord progression has a basic similarity to ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’ (as described in an earlier blog post), and then remember the similarity of m. 2 to the Parker lick in m. 5 of ‘Anthropology’ and m. 31 of ‘Confirmation’, and the similarity of m. 7 to the same measure in the opening strain of Scott Joplin’s ‘The Entertainer’, memorizing the rest of the tune becomes a matter of making connections to these landmarks (m. 1 is a nearly exact inversion of m. 2; m. 3 is an alteration of m. 7 that resolves to the root rather than the V chord, etc.)

‘Ornithology’ has the unusual status of being a piece of music assembled from a legendary player’s vocabulary by an admiring associate which subsequently became a theme song for the legendary player. When I mentioned the idea of ‘Ornithology’ as a kind of musical ‘fan fiction’ to a group of students, and asked whether fan fiction has ever been used by the author who inspired it, one of them mentioned that the author J.K. Rowling has incorporated characters from Harry Potter fan fiction into her own Harry Potter books. But on the musical side, the question remains – have other jazz players (or any musicians for that matter) been able to incorporate music written in their honor into their repertoire as successfully as Parker did? I would welcome any responses to this question in the comment section, and any other thoughts about recycling of melodic motives by Parker or other improvisers.