(or: From Hellish To Hopeful: the exoneration of the tritone in western music)

In the late 1970s, a group called Florida Orange Juice Growers sponsored an ad campaign to spread the message that orange juice could be consumed at any time of day, not just in the morning. The slogan was ‘Orange Juice: It Isn’t Just For Breakfast Anymore’. A battalion of spokespeople, from celebrities to the average Joe and Jane, were enlisted to make the case in a series of thirty-second TV ads. In one dizzying spot, ice skater Peggy Fleming (who seems to have trouble keeping a straight face after skating to a glass of orange juice), conductor Arthur Fiedler of the Boston Pops, and a young girl identified as ‘Linda Harris’ all testify to enjoying the beverage at times of day other than breakfast. Another spot that followed the two-celebrities-and-a-kid formula featured testimonials from golfer Arnold Palmer, then-singer Kathie Lee Johnson (later Kathie Lee Gifford), and a nameless boy who inspires envy from the voiceover guy (‘hey, I’d like to try orange juice with a hamburger’.) Evidently a theory was afoot that a nameless child might be more persuasive than a named one. Anita Bryant rode ‘aboard a thrilling airboat’ to ‘one of Florida’s fabulous resorts’ to interview mostly grandparent-age guests who proclaim their love of orange juice. The appropriately named Robert J. Lemons of Fairfield, Illinois tells Bryant: ‘I often drink a glass of orange juice before going to bed’.

Although the ads threw together oddly chosen celebrities, ordinary adults and children with all the randomness of a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade float, they were apparently effective. A 2004 research paper by the Florida Department of Citrus noted that ‘Over the 1967/68 to 1999/2000 period of analysis, FDOC expenditures on orange juice advertising increased the demand for orange juice in each year by an average of 388 million gallons (SSE) and boosted the annual average price of orange juice by $0.23/16 oz’. Even though this research is from a biased source, if the figures are anywhere near accurate, that is a staggering return on an advertising investment.

Ironically, orange juice has become a pariah in the health news of recent years. In 2016 Business Insider ran an article titled Orange Juice Is Being Called A Massive Scam, which mentioned that orange juice sales had declined by 13% over the previous four years. While the article was a roundup of other recent articles, not a research or opinion piece, and I can’t attest to the veracity of its sources, it does roughly indicate a trend of thought about orange juice and a certain truth about marketing and media. The fate of orange juice, like many commodities, rides on an ever-changing tide of public opinion, which can be affected by something as seemingly unpersuasive as celebrities, children and everyday adults appearing in commercials in groups of three. The ‘not just for breakfast’ campaign was like a marketing version of the Christmas story where different groups of three Magi keep arriving at the cradle of the American consumer, blessing the once and future grocery shopper with the wisdom that they are free to drink orange juice at any time they choose.

The interval of an augmented fourth or diminished fifth (for example, the interval from F to B in the C major scale, or from Bb to E in the F major scale) was famously termed the ‘diabolus in musica’ (the devil in music) around the time in the Middle Ages that hexachord system was articulated by the music theorist Guido of Arezzo, who lived from around the year 991 to sometime after 1033. The hexachord is a six-note scale including the first six degrees of the major scale, but excluding the possibility of a tritone by omitting the seventh degree (a tritone would occur if a melody included a leap from the fourth to the seventh). The sound of this musical system can be heard in the hymn Ut Queant Laxis, probably composed by Guido. Palisca and Pesce write in Grove Music Online that ‘Although the text of the hymn Ut queant laxis is found in a manuscript of c800 … the melody in question was unknown before Guido’s time and never had any liturgical function. It is probable that Guido invented the melody as a mnemonic device or reworked an existing melody now lost.’ Each line of the text Guido chose begins with one of the syllables in the system of naming notes of the scale that he invented (ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la – the precursor of the solfege method used by music teachers today who use the system designed by Zoltan Kodaly.) One can hear in Ut Queant Laxis the tritone-free sound world that the often anonymous composers of the middle ages considered evocative of holiness and the divine.

If you can go with me on an admittedly long walk of a comparison, and I hope you can, the tritone in the middle ages had something in common with orange juice in the mid-1970s, before the dawn of the ‘not just for breakfast’ campaign. It had an image problem, but not one that would not be improved in a few years, like the image of orange juice was in the late 70s. The image, one might say the typecasting, of the tritone in Western music would improve gradually, over many centuries of musical history. The tritone would not be exonerated from the judgement passed on it in the middle ages until eleven centuries later, when jazz and jazz-influenced composers would realize its greater potential.

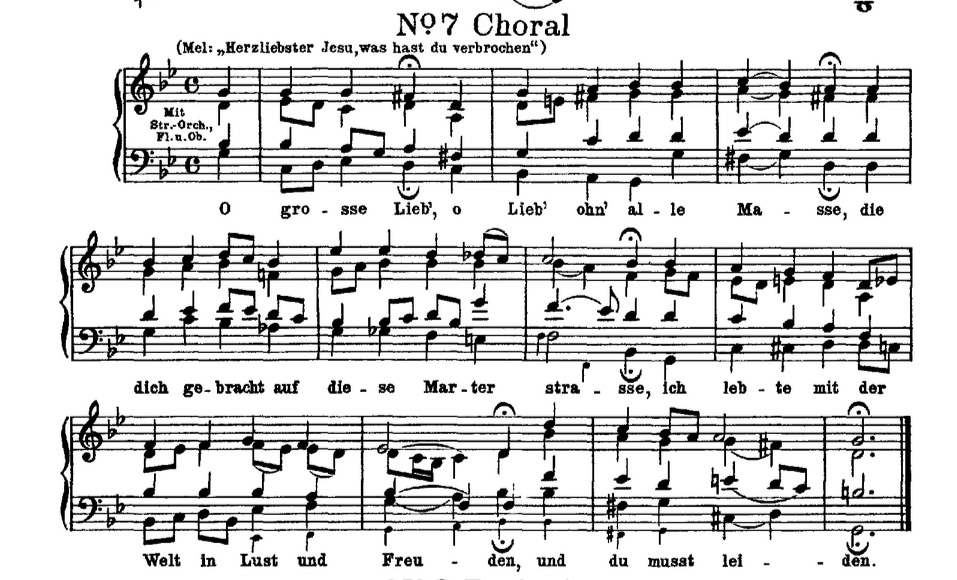

By the Baroque area, the major scale had expanded to include the seventh degree, and instead of excluding the tritone, composers of church music began to use the interval to evoke pain and evil. The Chorale ‘O Grosse Lieb’ (O Great Love) from J.S. Bach’s ‘St. John Passion’ expresses the Baroque-era Protestant interpretation of the Gospel narrative: that Jesus’ death and resurrection redeems the sins of individual Christians through all of history following his time on earth. The choir, who observe the story of Jesus’ death and passion during the piece, address him and say: ‘I lived amongst the world in joy and pleasure, and you must suffer’. (This English translation by UVM’s own professor emeritus Z. Philip Ambrose, can be seen side by side with the original German on page two of this document.) On the last two words of the text (‘must suffer’, or ‘must leiden’ in German) sing a descending tritone (C to F#) . We can observe that in the church music of the middle ages, the tritone represents evil itself, which leads to its being banished from music, while in the Baroque era, the tritone represents the pain caused by evil, and so it can be included as part of a complete musical depiction of the struggle between sin and salvation. Leave a comment in the comment section if you can find the timing in the video where the tritone is sung in the bass part. Here is a score for the chorale:

Charles Gounod’s opera Faust is based on the story, interpreted by many authors in many eras, of a man by that name who makes a deal with the devil. When the character Mephistopheles, described by one interpreter as ‘an agent of Lucifer’, makes his entrance, the first two notes he sings (to the word ‘pardon!’) are a descending tritone (Db-G). These notes initiate a recitative passage that is followed by Mephistopheles leading a boozy crowd in the ‘Song Of The Golden Calf’. Here is a link to a score for the beginning of the recitative and the song. (Before Mephistopheles’ song, the crowd have recently sung the chorus ‘Wine or Beer’, including the words ‘may my glass be full! Cup upon cup, without shame’.) Mephistopheles’ song references the story from the Hebrew Bible in which the Hebrews worship a false god in the form of a golden calf while they are waiting for Moses to return from the mountain where he receives the tablets with the Ten Commandments. Mephistopheles sings ‘you shall bow to the Golden Calf! / for it holds majestic power…kings and rulers kneel before him, great and humble, young and old / none resist the lure of gold as they slavishly adore him…dancing round his pedestal / Satan leads the merry ball, the merry ball, the merry ball’. This last line is sung twice, and on both repetitions the second ‘merry’ is also a tritone. Leave a comment in the comment section if you can find the timing in the video where either or both of the tritones are sung (somewhere within the French text ‘Et Satan conduit le bal, conduit le bal, conduit le bal’).

On the second verse Mephistopheles is joined by the crowd in this refrain, as though they have learned the song from him. After their earlier ‘Beer Or Wine’ song, which was tritone-free and comparatively lighthearted, the chorus taking up Mephistopheles’ song with its repeated tritones musically symbolizes his turning them from simply irreverent revelry to true evil. Gounod is described as ‘a devout Catholic all his life’ who seriously considered becoming a priest. He was a great admirer of J.S. Bach’s music, most famously composing his ‘Ave Maria’ melody using Bach’s C Major Prelude from the Well Tempered Clavier Book I as an accompaniment. In ‘Song Of The Golden Calf’ it is perhaps his Catholicism that leads him to see the tritone as the personification of evil, much as his fellow Catholic Guido of Arezzo did. The ‘Ave Maria’ melody suggests that he may have followed Guido’s prohibition against tritones in his religious music; the melody is tritone-free, although it floats above an accompaniment by his Protestant predecessor that includes a number of beautiful tritones in its perpetual motion. Leave a comment in the comment section if you can identify any of the timings in this scrolling video of the Ave Maria score where the tritones occur in the treble clef piano part; please also name the two notes that form the tritone. In ‘Faust’, Gounod includes the melodic tritone as a storytelling device, much as Bach does in the ‘St John Passion’. In ‘Faust’, however, the tritone represents an evil that cannot be reformed, while the tritone in Bach’s ‘O Grosse Leib’ represents suffering that redeems sins.

In the twentieth century, two composers, one from the jazz tradition and one inspired by it, found ways to make melodic use of the tritone that preserved the mystique that led it to be banned by Guido and used by Bach and Gounod as a symbol of pain and evil, but also freed the tritone from a musical world where all sounds are either heavenly or evil. In Thelonious Monk: The Life And Times Of An American Original, Robin D.G. Kelley writes that Monk’s composition ‘Round Midnight’ had two sets of lyrics written to it. Monk collaborated with lyricist Thelma Murray on an earlier version called ‘I Need You So’. After Monk changed the title to ‘Round Midnight’, lyricist Bernie Hanighen wrote lyrics that repeated Monk’s title phrase a total of seven times over the tune’s thirty-two bar form. Both sets of lyrics express the particular loneliness of being separated from a beloved person, which demonstrates that Monk’s composition implies that sentiment even when played instrumentally (as it often is to this day.)

Note: The reference version I have linked to in the last paragraph is by Julie London, who sings the tune with pitches that stay closer to the published melody than most jazz interpretations. Monk’s own versions, starting with his 1947 recording, all add a great deal of interpretation, i.e. additional melodic motion, to his own published melody line. Perhaps this was in an effort to distinguish his version from the one by Cootie Williams, whose version preceded Monk’s and stayed close to the published melody.

Hanighen’s lyrics describe how a time of day can bring on a mood. One also has to wonder whether Hanighen, who worked as a lyricist and producer, had some awareness of the tritone’s history of being typecast as evil, because his lyrics manage the quietly radical act of transforming Monk’s repeated tritones from ominous omens to hopeful ones. Here are the lyrics for the first eight bars of the song, with the words accompanied by tritones in the melody in bold:

It begins to tell ‘round midnight, ‘round midnight

I do pretty well till after sundown

Suppertime I’m feeling sad,

But it really gets bad ‘round midnight

Hanighen places the word ‘feeling’ (of the phrase ‘feeling sad’) on the second tritone in Monk’s melody, which descends in contrast to the ascending tritone on ’till after’. The descending tritone on ‘feeling sad’ is a very similar pairing to Bach illuminating the words ‘must suffer’ with a descending tritone in ‘O Grosse Leib’. While the opening of the song could be about many kinds of loneliness, the cause of this particular heartache is revealed in the second eight-bar phrase: ‘when my heart is still with you / and old midnight knows it too’ (lyric accompanying the tritone in bold). Hanighen’s lyrics to the bridge continue the story, and incorporate three words from Thelma Murray’s original lyric:

When some quarrel we’ve had needs mending,

Does it mean that our love is ending?

Darling, I need you; lately I find

You’re out of my arms and I’m out of my mind.

In the last eight bars, Hanighen unites Monk’s next to last tritone with an image of the divine (lyrics accompanying the ascending tritone in bold):

Let our love take wing, some midnight, ‘round midnight

Let the angels sing of your returning

Hanighen’s lyrics illuminate the last descending tritone in Monk’s melody with a wish, perhaps a prayer, for a positive resolution to the story: ‘let our love be safe and sound’. While Bach and Gounod associated the tritone so strongly with pain and evil, Hanighen and Monk lift the curse when their conclusion to ‘Round Midnight’ unites the interval first with the divine (the angels sing a tritone!) and then with healing (‘safe and sound’). A sign of the power of this concluding section is that when vocalist Samara Joy sang Jon Hendricks’ melancholy yet optimistic alternate lyrics to the song on her Grammy-winning album Linger Awhile, she still incorporated Hanighen’s lyrics to the last eight bars. Leave a comment in the comment section if you can identify any of the timings in this wordless vocal version by Bobby McFerrin and Herbie Hancock where the tritones in the melody occur, and give the letter names of the notes in each tritone.

‘Round Midnight’ was one of Monk’s earlier compositions, and its repeated and prominent tritones are a hint that the interval will become a defining feature of his melodic style. Among the many Monk tunes featuring frequent tritones is Five Spot Blues from the 1963 album Monk’s Dream, a slight but significant revision of his earlier ‘Blues Five Spot’ which I discuss in my post How To Write A One Bar Blues.

While it’s not clear how aware composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein was of Thelonious Monk’s music, he was certainly ‘jazz curious’, from the evidence of an educational record he made in 1957 called What Is Jazz and the musical West Side Story, which premiered the same year. The score to this show includes music, particularly the Cool Fugue (the midsection of the song ‘Cool’, discussed below), that demonstrates Bernstein had a serious interest in the bebop melodic language that was becoming the common practice of improvisers at the time. It also includes at least four songs that not only prominently feature tritones in the melody, but share a leitmotif – a three note phrase that appears in all the songs beginning with a tritone.

In the opening ‘Jet Song’, the eponymous violent street gang sing ‘we’re drawin’ the line’ with a descending tritone on the last two words. In this song, the tritone symbolizes their potential for violence, as it does for Mephistopheles in Gounod’s Faust. However, in the next song, ‘Something’s Coming’, Tony, the Romeo character and a former Jet who has just been drawn back into the gang, sings the same three note motive to the lyrics ‘could be? / who knows?’, as the prelude to a song expressing a premonition of a positive, transformational event in his life (‘I got a feeling there’s a miracle due, gonna come true, comin’ to me’), recasting the tritone as a symbol of hope, as it is by the end of ‘Round Midnight’.

Tony’s premonition comes true in a dance that night at the gym where he meets Maria, a recent Puerto Rican immigrant with family ties to the Sharks, a gang who are challenging the Jets for territory. While the rest of the Jets leave the dance eagerly anticipating the rumble to which they have just challenged the Sharks, Tony leaves reveling in his attraction to Maria, singing her name over and over with different melodic patterns (sometimes augmented by backstage or recorded voices) until he sings it with the three-note, tritone-based leitmotif. (Given that the song’s music was written by a very gifted composer and a lyricist who was also a a gifted composer, it’s only natural that Tony at this point in the song sounds like a composer trying to find the ideal melodic pattern for a three syllable name.) Where the tritone was a descending interval in the first two songs, it is now ascending, a musical gesture that together with Stephen Sondheim’s lyrics expresses how speaking the name of the beloved can hold a spiritual power (‘Maria / say it loud and there’s music playing / say it soft and it’s almost like praying’). Leave a comment in the comment section if you can identify the phrases other than the word ‘Maria’ where the three-note leitmotif is used, either by lyrics, the timing in the video or both.

In an interview with Rolling Stone quoted in the Wikipedia article on West Side Story, Bernstein mentioned that when the show was in development, the frequency of tritones in the score was one of the reasons its early opponents gave that it could not succeed: “Everyone told us that [West Side Story] was an impossible project … And we were told no one was going to be able to sing augmented fourths, as with “Ma-ri-a”. One has to wonder whether the opponents of Bernstein’s score were concerned not just with how frequently he used tritones, but with how his music together with Sondheim’s lyrics gave the tritone a non-traditional role, associating it with positive aspects of the story and not just negative ones.

When the Jets take up the ascending-tritone motive in the next song, ‘Cool’, it is in the context of a kind of counseling session where an older Jet (in the 2021 film version, Tony himself) advises a younger one on the mindset of a successful gang member, and the potential rewards of the profession (‘don’t get hot, cause man, you got some high times ahead / take it slow, and Daddy-o, you can live it up and die in bed’). While the tritone makes its first appearance in West Side Story in its traditional role of symbolizing evil, Bernstein and Sondheim, like Monk and Hanighen, show that the interval is versatile enough to also symbolize possibility, hope and love. (Besides the ‘Maria/Cool’ theme, another theme of the ‘Cool’ fugue midsection is the first three notes of ‘Somewhere’, a tune discussed in my post Sevenths Reaching For The Heavens.)

To return to television where this essay started, in 1989, composer Danny Elfman began his theme music to the long-running cartoon series The Simpsons with the same three-note leitmotif Leonard Bernstein used in ‘Maria’ and ‘Cool’. It seems impossible that Elfman wasn’t either consciously or subconsciously inspired by the presence West Side Story and those songs in particular have maintained in American culture during his lifetime (he was born in 1953, four years before the show’s premiere). The show has been revived on Broadway four times, the film has stayed in circulation in various ways, and versions of the songs have been recorded by artists including Buddy Rich, Judy Garland, Barbra Streisand, Oscar Peterson and The Supremes.

Each episode of the Simpsons begins with the family’s name being sung with the same three notes that Tony in West Side Story uses to announce his love for Maria, his anticipation of an exciting future with her. While Tony dies by the end of Act Two in West Side’s tragic story arc, Elfman’s use of the ‘Maria’ motive at the beginning of each ‘Simpsons’ episode has helped television audiences feel a sense of anticipation for the 35 years (and counting) that the show has been on the air and making new episodes. (It is currently television’s longest running scripted series, currently at 781 episodes.) The theme’s opening continues to make audiences fall in love with the sound of the Simpsons’ name, much as Tony fell in love with the sound of ‘Maria’, and they stay Cool because they know Something’s Coming. As I have tried to show, it is thanks in part to Thelonious Monk, Bernie Hanighen, Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim that when Simpsons viewers, whether they have seen zero episodes or all 781, hear the beginning of the opening theme, their first thought isn’t that they’re in for redemptive suffering or the entrance of a Satanic character (though there is room for both in the vast Simpsons universe). Their first thought is: ‘Something’s Coming / I don’t know what it is / but it is gonna be great’.

©2025 Tom Cleary

This is a really informative essay – thank you for posting. I am just learning my tritone substitutions for jazz guitar, which look to be quite useful. I knew it had been dubbed the ‘devil’s interval’ but the full history is quite interesting.