British bandleader Ray Noble published his tune ‘Cherokee’ in 1938. The tune begins with a chord progression that could be described as I – I7 – IV – iv – I. In this progression, the tonic chord becomes a dominant seventh that leads to the IV chord, which is then followed by either the minor IV or a dominant chord based on the flat 7th of the tonic major scale, which in turn leads back to the I chord. Although this progression appears in earlier pop tunes such as ‘Tonight You Belong To Me’ , first released in 1927, ‘Cherokee’ is perhaps the best known tune in the modern jazz repertoire to use these chords. One possible reason for the longevity of ‘Cherokee’ is it that spends two bars on each of the changes in the progression, which gives improvisers a chance to ‘stretch out’, i.e. develop longer melodic ideas, on each chord.

The progression also appears in Duke Ellington’s ‘Do Nothin’ ‘Til You Hear From Me‘, the 1947 update of Ellington’s 1940 composition ‘Concerto for Cootie’ with Bob Russell’s lyrics added. Ellington’s tune opens with the ‘Cherokee’ progression but spends only a measure on each chord. (I am using the term ‘Cherokee progression’ for ease of reference, not to imply conclusively that it was borrowed by Ellington from ‘Cherokee’.) In 1945, Billy Eckstine released his tune ‘I Want To Talk About You‘, which begins with the shortened ‘Cherokee’ progression that appears in the Ellington tune. The melody of this tune mostly emphasizes the triad tones of each chord in the progression. 1955 saw the release of pianist Erroll Garner’s recording of his tune ‘Misty’, which uses much of the progression of ‘I Want To Talk About You’ but substitutes a different melody that emphasizes upper chord tones (such as the 7th in the first measure, the 9th and the 13th in the second and fourth measures) rather than triad tones. On Garner’s original recording of the tune, his emphasis on chord extensions in the right-hand melody mirrors his left-hand chord voicings, which combine root position voicings with rootless voicings – voicings built on degrees of the chord other than the root, particularly the third and seventh, and in which chord extensions are emphasized through their placement on the top of the voicing. These are often called ‘Bill Evans voicings’ because they were used so prominently by the younger Evans, but they appear earlier in the playing of Garner and Garland. Garner, along with his slightly younger contemporary Red Garland, was one of the players who introduced rootless voicings into the left-hand vocabulary of jazz pianists. Prior to ‘Misty’, one of Garner’s contemporaries and collaborators, Charlie Parker, released a recording called ‘Koko‘ in which he improvised a melodic line over the chord progression to ‘Cherokee’ that at a number of points arpeggiates rootless voicings of the chord changes.

A number of pop songs from the 1960s and 70s, including The Beatles’ ‘Dear Prudence‘, Billy Preston’s ‘You Are So Beautiful‘ and Earth, Wind and Fire’s ‘That’s the Way Of The World’, derive their harmonic motion from looping the four chords with which ‘Cherokee’ begins. In 2015, Kamasi Washington brought ‘Cherokee’ full circle by combining it with a groove similar to that of ‘That’s The Way of The World’.

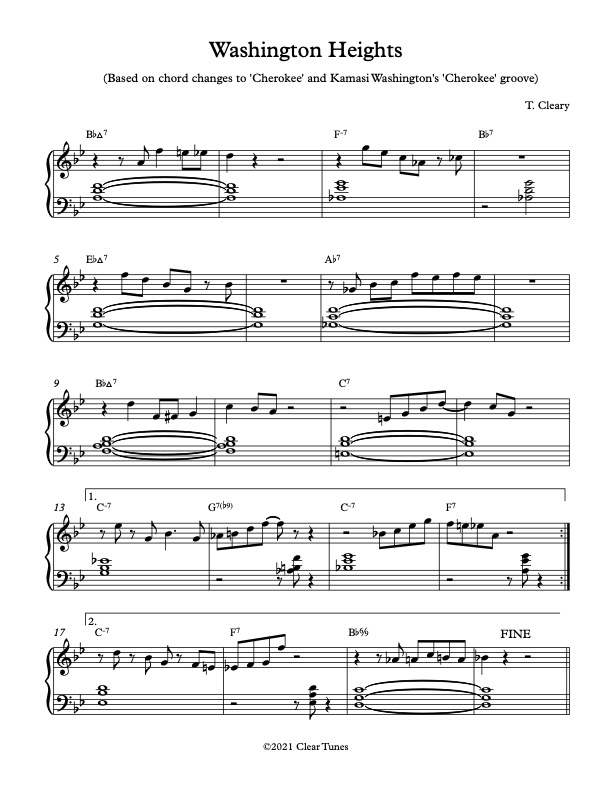

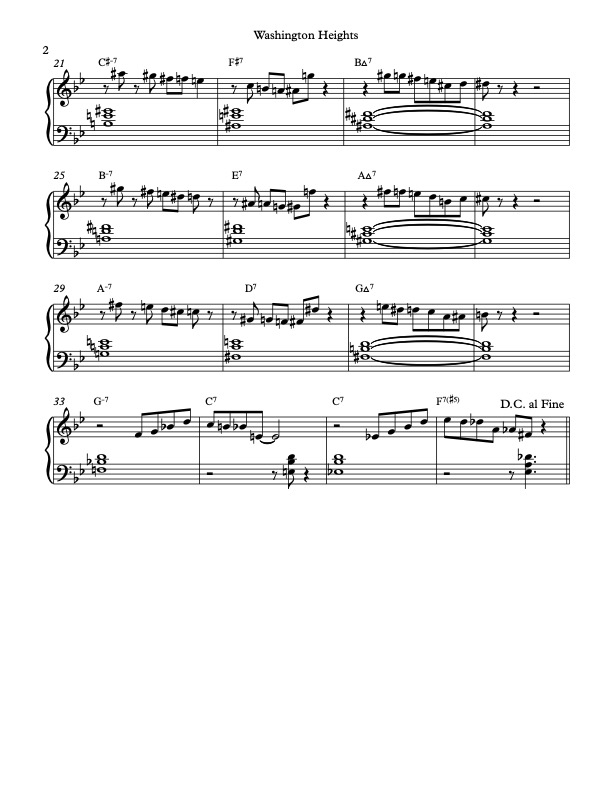

My tune ‘Washington Heights’, named after both the saxophonist and a neighborhood in New York City, uses the progression of ‘Cherokee’ with the groove from Kamasi Washington’s arrangement and adds a melody which I composed in the bebop melodic style. It also demonstrates two important concepts which I find helpful in improvising piano solos on jazz progressions: dialogic phrasing (left hand chording that leaves space for melodic answers and melodic phrases that leave space for chordal answers) and ‘crossless’ voice leading in the left hand chords (voice leading that avoids voice crossing.) While it can be learned as shown in the grand staff chart, another possible use is to memorize the original melody of ‘Cherokee’ and play it in the RH along with the LH voicings from ‘Washington Heights’, either with the written rhythms or with the chords in long notes. The A sections of ‘Washington Heights’ (m. 1-20 with repeat) also work as a countermelody to the A sections of ‘Cherokee’.

It’s so interesting how a musical idea can “evolve” through time in a way, in which it’s imprints can be traced back years and years to the original, which in turn was most likely based on some other musical idea. I think a major reason why Cherokee has lasted this long is due to the simplicity of the piece, making it open to interpretations and additions by other artists. I’ve seen things similar to this in regards to more modern music. The video game “Minecraft” is very much a cultural staple, and it’s soundtrack is simple enough that I’ve heard bits of its more signature musical ideas in other artists work, such as in the chorus of Cavetown’s “Worm Food”.

I think it is really cool how songs with the same pattern of chord progressions can produce such different sounds. If I were to compare “I Want to Talk About You” with “Washington Heights” it would be my initial thought that they are two completely different songs with little to nothing in common. I would think this due to their respective melodies, feel, tempo etc., but when thinking about how they share chord progressions we can see how they may have been inspired by one another, or by a third ‘party’, in this case “Cherokee”. It reminds me of books in a way, how in English literature, every book is made up of different combinations of the same letters, but they all result in something completely different from one another. It’s up to each individual to create something that distinguishes their piece from the rest, in the case of literature it would be the plot, and in the case of these songs the melody, groove, feel, etc. In a way, it is also similar to improvisation. When a group improvises on the same song, it is up to the individual to make it their own, and consciously or not, each person brings something unique to the table. These examples all demonstrate merely a fraction of how grand the scope of creativity is, which is always an interesting topic to explore.

It’s very fascinating to learn about compositions that share famous chord progressions, because to the average ear it would probably not always be as obvious compared to a musician. Specifically in Washington Heights, the chord progression crosses over in a way that was subtle to me at first. Looking at the score, the ii V I progression in the first ending (m. 13-17) sounded so distinct next to the appearances of C-7 F7 BbM7 in Cherokee. I think this is partially due to the melody setting a different mood in each of the tunes. Most of all, the short chords in the left hand being on the and of 3 creates a stark sound that is not present in Ray Noble’s 1938 Cherokee.

What a fascinating exploration of the “Cherokee” progression! It’s amazing how this harmonic structure, from Ray Noble’s 1938 tune, has influenced everything from jazz standards like Misty to pop hits like Dear Prudence. Your own composition, Washington Heights, beautifully merges the Cherokee progression with Kamasi Washington’s groove and bebop melodies, showcasing how dialogic phrasing and crossless voice leading can create space between harmony and melody.

This reminded me of Charlie Parker’s Ko-Ko, where he brilliantly improvises over the Cherokee progression, shaping the jazz language we know today.

It’s incredible how a progression like Cherokee continues to inspire new music across genres, showing the power of reinvention. Thanks for sharing such an insightful post!

Charlie Parker’s Ko-Ko: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=La0k9t5ce_k

Fascinating breakdown of the ‘Cherokee’ progression’s legacy—especially how it continues to inspire modern reinterpretations like ‘Washington Heights.’ The way harmonic frameworks evolve across genres is something I explore often, even in unexpected spaces like game modding and design carxstreetsmodapk.com

. Appreciate the depth in this piece!