In 1962, the first film in the James Bond series, ‘Dr. No’, was released. As ‘Dr. No’ was a great success at the box office, Bond films continued to be released almost annually over the following decade, each one using a number of elements that had been introduced in ‘Dr. No’. These included character of Bond himself (always introduced through an opening sequence featuring the opening Bond theme), and the archetypes of the ‘Bond girl’ and the ‘Bond villain’. The third Bond movie, ‘Goldfinger’, added the trope of the Bond vocal theme song to the formula, a franchise which over the years has passed through a long list of pop song composers and performers, including Shirley Bassey, Louis Armstrong and most recently Billie Eilish.

1962 also saw the release of ‘Takin’ Off’, the first album by jazz pianist (and future film composer) Herbie Hancock. As Hancock recalls in his autobiography, Possibilities, the album “climbed to number 84 on the Billboard 100. At that time Billboard didn’t have different charts for different genres, like pop, jazz and R&B. There was just one chart for all the records released, so for a jazz record to reach the top 100 was considered pretty good. ‘Watermelon Man‘ was the single that propelled the record, and when I started hearing it on the radio, it was really cool.” Hancock goes on to describe how the success of his version of ‘Watermelon Man’ was eclipsed when a version by Cuban bandleader Mongo Santamaria reached number 11 on the Billboard 100.

Much as the success of ‘Dr. No’ led to a series of films that sought to capitalize on its success, I would argue that the success of ‘Watermelon Man’ led to a series of tunes, many by Hancock himself, that focused on not so much replicating the original as reinventing various aspects of it. Far from being ‘cheap knockoffs’, Hancock’s follow-ups to ‘Watermelon Man’ show his evolving resourcefulness as a composer. Blind Man, Blind Man, from Hancock’s 1963 album My Point of View, borrows the drum groove and the signature melodic rhythm from ‘Watermelon Man’, but in the context of a tune based on a single chord (rather than the four chords of the original.) On his 1964 album ‘It’s All Right’, Wynton Kelly (who by that time Hancock had replaced in the Miles Davis Quintet) recorded a tune called Escapade which uses a very similar chord progression to that of ‘Watermelon Man’, but with a different melody and what might be called a surf-rock drum pattern rather than the ‘funky’ backbeat Billy Higgins concocted for the original.

1964 also saw the release of Hancock’s concept album ‘Empyrean Isles’, which included ‘Cantaloupe Island‘, the title of which hints at its kinship with ‘Watermelon Man’. This tune, like ‘Watermelon Man’, has a 16-bar form and a similar bassline and piano accompaniment figure. The drum groove, while still ‘funky’ and based in straight eighth notes, is considerably different, and the chord progression is modal and uses predominantly minor 7th chords in contrast to Watermelon Man’s dominant sevenths. As Hancock’s website tells it, “The track was somewhat popular in the mid-60s, but it was not until the Hip-Hop band Us3 sampled the track and incorporated it into their mega-hit “Cantaloop” that anyone really took the song seriously.” Hancock’s 1973 album ‘Headhunters’ featured a completely transformed ‘Watermelon Man’ which reimagined the tune in the 1970s concept of funk, retaining only its progression (expanded to include one more chord, Ab7) and a vestige of its melody and otherwise completely transforming the tune with a new intro (which, percussionist Bill Summers explains, he composed and performed on a beer bottle), a new groove, and electrified instrumentation.

With this series of tunes, one can hear Herbie Hancock going through a methodic and yet highly creative process of building new pieces on different elements of the original ‘Watermelon Man’ – first the groove with ‘Blind Man’, then the form with ‘Cantaloupe Island’, and finally the chord progression with the electric ‘Watermelon Man’. While it makes sense that Hancock’s goals with these tunes were partly commercial in the sense of wanting to repeat or approach the chart success of ‘Watermelon Man’, each of these tunes was in my view also an artistic success, as Hancock, like Duke Ellington, as well as composers such as Bach, Beethoven and Brahms who were masters of the theme and variations form, has the gift of creating music based on an earlier piece which is totally new and not derivative.

During the period when this music was released, Herbie Hancock also scored the music to two films with plot lines roughly similar to the Bond films, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and Ivan Dixon’s The Spook Who Sat By The Door (1973). One of the themes from Hancock’s soundtrack to ‘The Spook Who Sat By The Door’ would, with the addition of a clavinet played through a wah pedal, become the tune ‘Actual Proof‘ from the album Thrust, released the year following the film (1974). The Blow-Up soundtrack is notable for including the outtake ‘Bring Down The Birds’, the intro of which was used prominently in the 1990 hit ‘Groove Is In The Heart’ by Deee-Lite. Here, as on ‘Escapade’ and ‘Cantaloop’, we can hear another artist building an entire piece on the strength of a Hancock idea. While these pieces all cleverly transplant Hancock’s ideas to other musical settings, they don’t display the ability that Hancock shows in ‘Blind Man, Blind Man’, ‘Canteloupe Island’ and the Headhunters ‘Watermelon Man’ to reinvent and transform musical ideas.

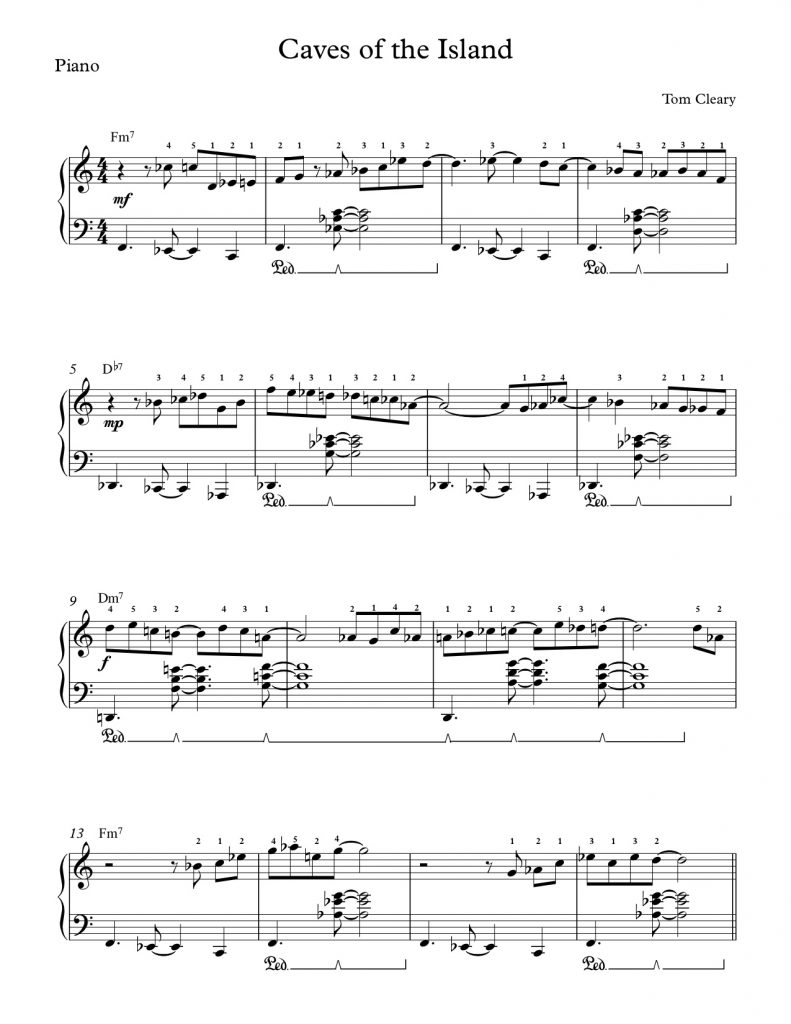

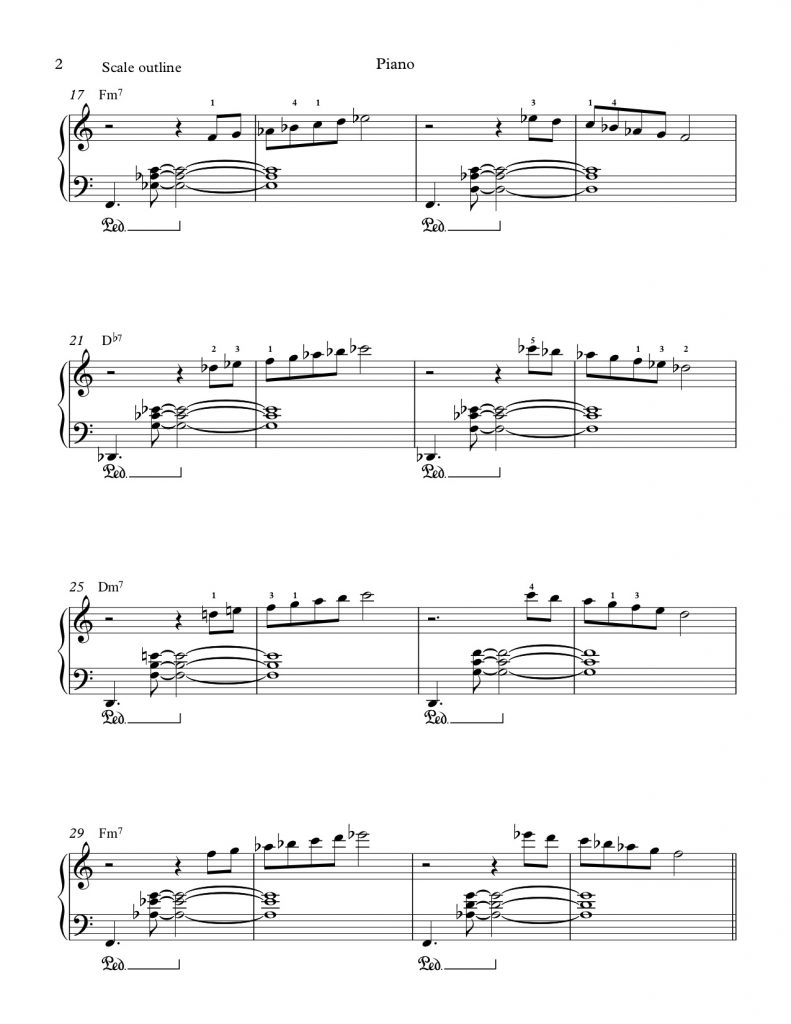

My tune Caves Of The Island is based on the chord changes to ‘Cantaloupe Island’, but uses a half time drum groove, different bass line and a chromatic, bebop-type melody. (A piano chart for it, including a scale outline, is below.) I was able to give Herbie Hancock a score to the tune when I met him backstage after a performance in Burlington. I handed him the chart, mentioned that it was a sort of bop tune, and was delighted when he began sight singing it immediately (after having played a two hour concert with no intermission!). Like many of my tunes based on existing progressions, this tune works both on its own and as a countermelody to ‘Cantaloupe Island’. Like many countermelodies, the line in ‘Caves of the Island’ often harmonizes with the melody to ‘Cantaloupe Island’ by moving the opposite direction from it (or in ‘contrary motion’, to use a common musical term.)

The liner notes to Empyrean Isles, by Canadian novelist Nora Kelly, describe the album as a depiction of a fantastical remote world that includes a mysterious mountain called ‘The Egg’, the ‘mythical Oliliquoi Valley’ which casts a hypnotic power on visitors, who during their hypnosis learn a dance called the ‘One Finger Snap’. (All these elements are represented by different songs on the album. ‘Oliliquoi Valley’ has a possible kinship with ‘Cantaloupe Island’, as it opens on a similar – although more chromatic – F minor tonality, and its opening bassline and chord pattern is a kind of two-bar variation on that of ‘Cantaloupe’.) I imagine ‘Caves of the Island’ as depicting part of the ‘upside down’ of Cantaloupe Island (in the sense in which that phrase is used in the Netflix series ‘Stranger Things’ to refer to a parallel world.)

I encourage anyone reading this post to respond in the comment section with any examples they can think of where ‘remakes’ have been attempted in literature, film or music, or to post a link to a piece of their own that seeks to ‘rewrite’ an existing tune or reinvent an element of it.

Awesome post, TC! So cool that you got to share your composition with HH himself. I’m also a huge Herbie lover (especially the funky stuff)! There’s an interesting back story to the intro of the Headhunters version of Watermelon Man – it was itself a kind of re-versioning of a recording of traditional Central African Pygmy music performed by Bill Summers (that’s not an ocarina!) Check out this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YcGZfVehez0 as well as this informative but also kind of depressing one: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yx_AF9TWv0g

As someone who discovered jazz in college, it was really nice to learn more about Hancock and his deliberate reinvention of “Watermelon Man”. To be able to find so many different avenues out of one piece of music, just is a reminder of how vast and creative a world jazz allows for. It’s so cool that you were able to share your piece with him !

When reading this it reminded me of the many late 90s and early 2000s films that would evolve great tales of Shakespeare into romantic comedies for teens. “10 Things I Hate About You” after the “Taming of the Shrew” or “Romeo and Juliet” staring Leonardo DiCaprio. They took the pieces of the original literature and reimagined it for the youth of the time. Pretty much all of Shakespeare plays, poems and stories have been developed over and over again. It’s interesting to watch how generations later the creativity is still building on one man’s idea or for Hancock how his idea keeps finding a new way to form itself.

Hi Katie, Thanks for the comment. Your mention of modern revisions of Shakespeare as a parallel to Herbie Hancock’s reinventions of his own tunes is fascinating. There is also a great Shakespeare-related piece in the classic jazz repertoire, Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn’s suite ‘Such Sweet Thunder’, in which each movement references a different Shakespeare play. The Romeo and Juliet movement, ‘The Star Crossed Lovers’, is one of the best known; here’s a great version by pianist Hank Jones with tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano (ignore the mismatched album cover in the video): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zg35BSkVVJ4… there are also a few movements based on sonnets; here’s a great version of ‘Take All My Loves’ by vocalist Darius de Haas: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FA00mLH8_Fk

It was fascinating to see the progression of Herbie’s style from the original recording of Watermelon Man (a composition I can remember playing in the stands of football games with the pep band) to an utterly reinvented version with Headhunters. And on the topic of reinventing, I couldn’t help but think of Bill Evans’s rendition of “Suicide is Painless.” Evans creates a seemingly majestic composition of the theme song. He keeps the song’s main melody but makes it his own by reharmonizing the changes creating a much richer sound, upping the tempo, playing an intro at a slower tempo without the band, and throughout the song he changes the key from G major to Eb major then to B major (going down in major 3rds) all whilst taking solo breaks between the key changes (usually comping on one chord for the breaks). Although it isn’t nearly as experimental as Herbie Hancock’s transformation, it creates a whole new listening experience for those familiar with the original theme, and it’s also exciting within the context of where Bill Evans was at this point in his life. He was old and not the healthiest in his career, but he could still reinvent songs just to pass the time.

Hello!

I really enjoyed Caves of the Island and I find it fascinating that upon meeting Herbie Hancock he started to sight-sing your piece! Fantastic! I hope to one day gain that level of musicianship.

There have been many notable remakes in media, sometimes it seems that there are more remakes than original content (though I know this isn’t actually true). Though many probably do not know this was a remake, prior to the version of Dune with Timothee Chalamet and Zendaya, there was an original that came out on the 80s. My parents really like this version as well as the book series.

Another example that came to my mind (though I am not sure this is an example of remaking so much as the evolution) was the original version of “Tears Dry On Their Own” by Amy Winehouse. The original version, titled “Tears Dry” has a slower tempo and a more somber feel. That version is more well-suited to the tone and nature of the lyrics, but the upbeat tone in the more popular version provides a layer of irony that I really appreciate.

Thanks for the comment, Izze. I can see the parallel between Herbie Hancock’s compositions drawing on the Watermelon Man formula, the James Bond films drawing on that formula, and the older and newer Dune films. In addition to ‘Tears Dry On Their Own’ having been recorded multiple times by Winehouse, the song itself borrows the chord progression and arrangement of the Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell Motown hit, ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’:

https://youtu.be/IC5PL0XImjw?si=z-eOftWJPzoGeuRg

‘The Lodgers’ by the 1980s group The Style Council works a variation on the melody and chord changes of the chorus from ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’, while keeping the melodic rhythm intact:

https://youtu.be/Y_Nbngy7WDY?si=IS5_9kgfXLLRpvX1

Here is the original version of Tears Dry:

https://youtu.be/vklE72KZLMQ?si=BvTEl_KndiuYlqag

I particularly love how you describe the “Cantaloupe Island” evolution and the transformation in his later works like “Headhunters.” His growth as a composer is a great reminder of the power of reinvention and how certain musical elements can be reworked in endless ways. Your own composition, Caves of the Island, is a brilliant extension of that process. The harmonic connection to “Cantaloupe Island” and the counterpoint through contrary motion is a beautiful way of building on something familiar while forging a new path. I can totally imagine how exciting it must have been to share that score with Herbie Hancock himself!

Your post reminded me of a few other reinterpretations in music, especially in jazz. One that comes to mind is “A Love Supreme” by John Coltrane, which takes traditional jazz structures and pushes them into a spiritual and modal realm.

If we go outside of jazz, I can’t help but think of how “I Will Survive” has been reinvented countless times across genres, from disco to rock to even punk. It shows how one song can go on to live many lives, each adding something fresh while remaining connected to the essence of the original.

It’s fascinating to see how both musicians and composers—like Hancock—revisit and reimagine earlier works, not just to repeat success, but to push boundaries and explore new dimensions of sound. It brings to mind how Stranger Things takes its 80s nostalgia and flips it into something fresh—much like you describe with your own Caves of the Island echoing Cantaloupe Island in an “upside-down” way.

A Love Supreme by John Coltrane https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ll3CMgiUPuU

stranger things theme song: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-RcPZdihrp4