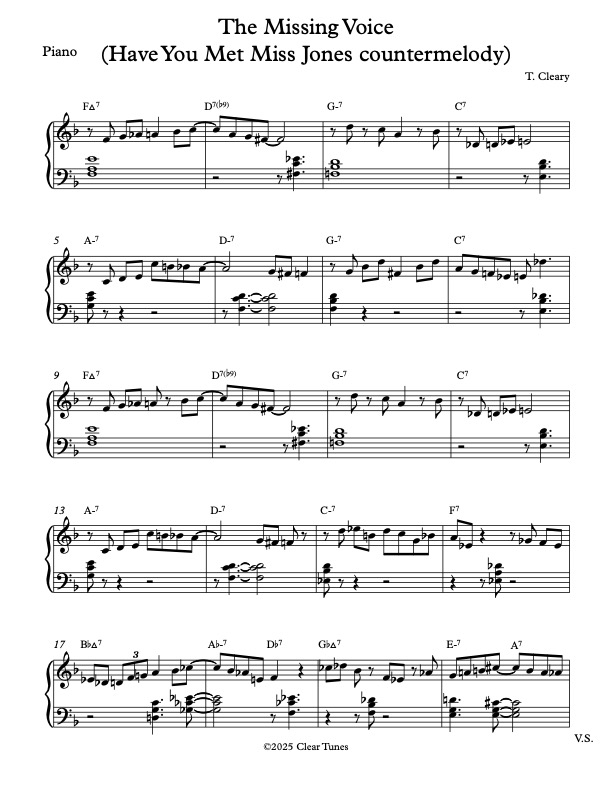

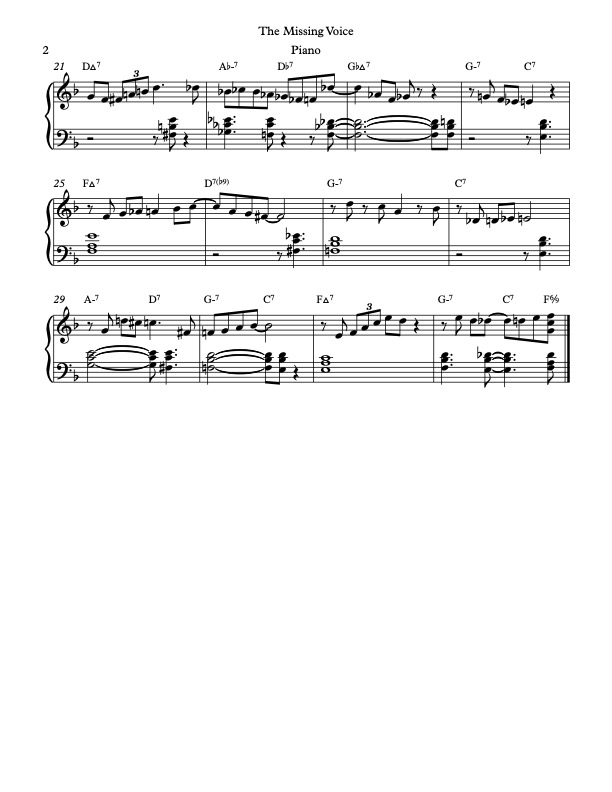

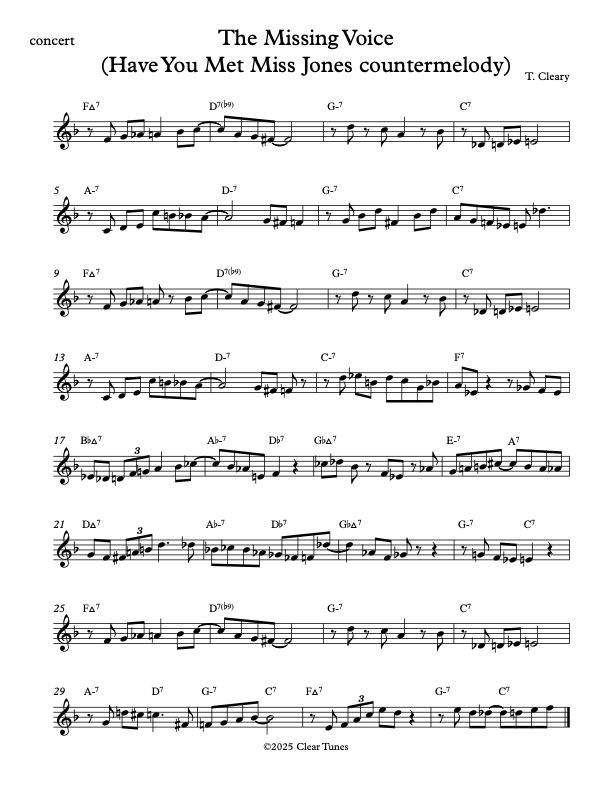

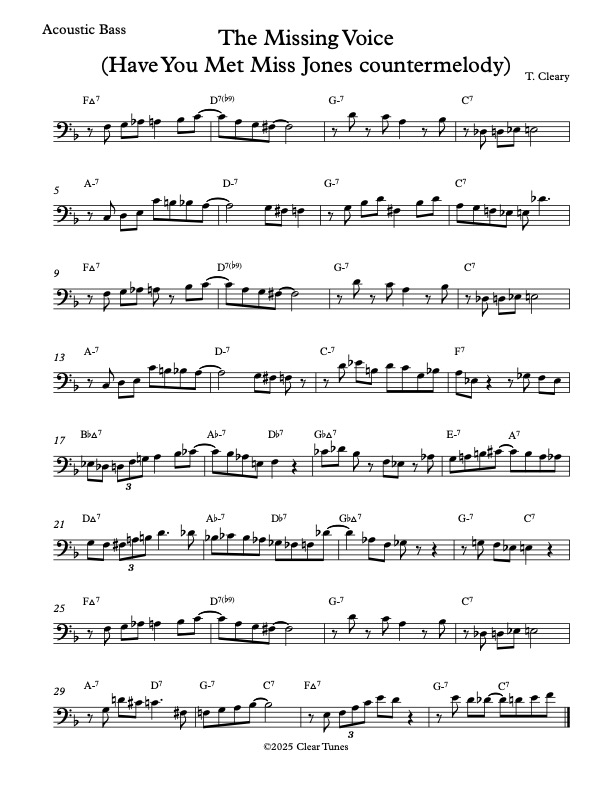

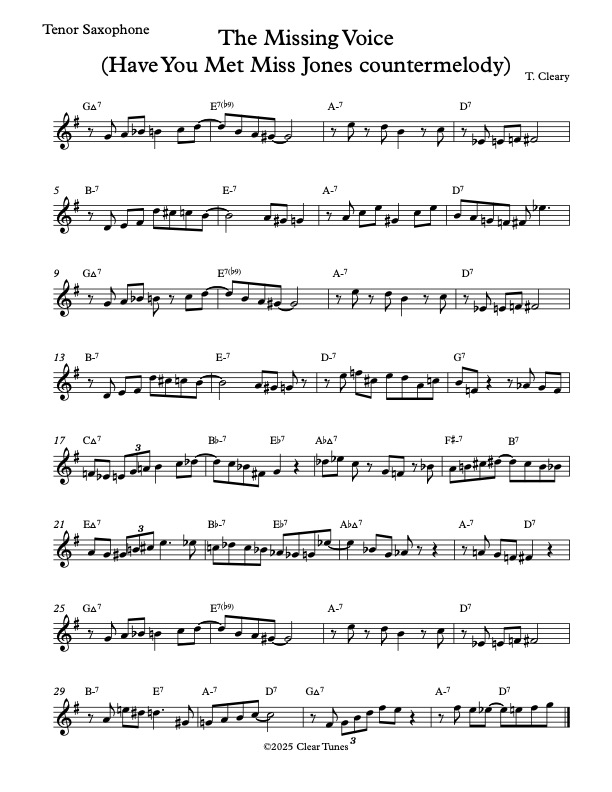

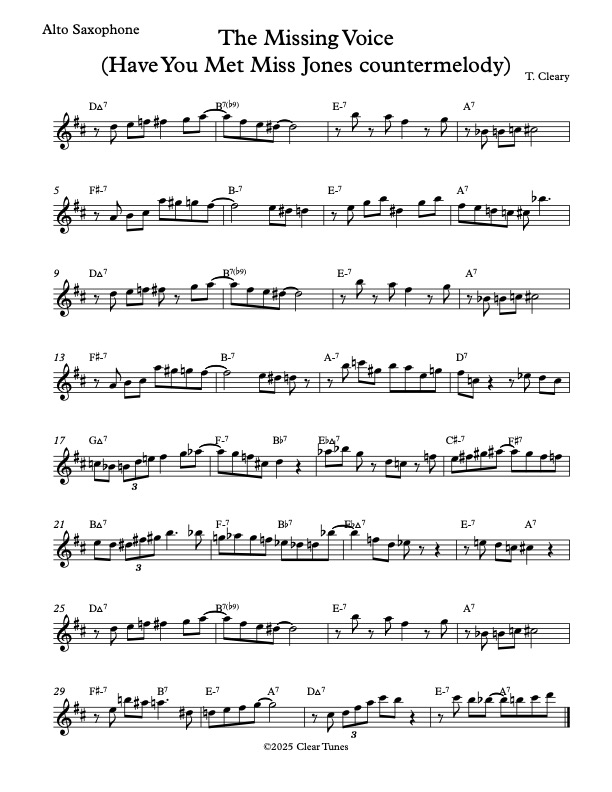

‘The Missing Voice’ is my original melody line on the changes to ‘Have You Met Miss Jones’ as they are shown in ‘All-Time Standards’ (Vol. 25 of the Aebersold book and playalong series). Here is a link to a rough recording I made of the tune using the iReal Pro record function. Charts of the tune are below this paragraph; please note that these include a revision to the last three notes which is more recent than the recording. Like my lines on the changes from other tunes used in Vermont All State Jazz Ensemble auditions, it includes licks borrowed from other sources (including Charlie Parker’s solo on ‘Now’s The Time’, Denzil Best’s ‘Move’, the old standard ‘Peg O’ My Heart’ and Ornette Coleman’s ‘The Blessing’) and it also works as a countermelody to the original melody. (As I’ve mentioned in past posts, I learned about the concept of a contrafact which is also an allusive countermelody from Benny Harris’s tunes Ornithology, Crazeology and Reets and I.) Please scroll below the charts for some background on the harmony and history of the tune, including links to some selected jazz versions.

Lorenz Hart’s lyrics for ‘Have You Met Miss Jones’ describe a man being introduced to a woman by a third person (‘Have you met Miss Jones / someone said as we shook hands’.) The speaker introduces himself to the woman in an odd way, by mentioning his apparent preoccupation with pushing boundaries: ‘Then I said Miss Jones / you’re a girl who understands / I’m a man who must be free’. There are a number of versions of the song by female jazz singers, including Ella Fitzgerald and Anita O’Day who reverse the gender roles by changing ‘Miss Jones’ to the knightly ‘Sir Jones’ and give a proto-feminist inflection to the line ‘I’m a girl who must be free’ (or ‘a gal who must be free’ in O’Day’s version). The link in the last sentence is to O’Day’s 1958 version from ‘Anita O’Day At Mister Kelly’s’, in which her solo takes after Ella Ftizgerald with the use of quotes from public melodic language (‘Rain, Rain Go Away’, “The Irish Washerwoman’, ‘Shave And A Haircut’). Here is a transcription, by my wife and UVM’s jazz voice teacher Amber deLaurentis, of O’Day’s solo from the version on her 1960 album ‘Anita O’Day and Billy May Swing Rodgers And Hart’.

Although in this version O’Day keeps her paraphrase of the original bridge from the Mister Kelly’s solo, she otherwise seems to largely refrain from obvious quotation. She does end her bridge with piece of lesser-known jazz melodic code, a four-note gesture (D-D-Bb-C) very similar to the one that Stan Getz uses (Db-D-Bb-C) at the end of the bridge during the head statement of his 1953 version (discussed below). Getz’s more chromatic version of the lick, which also appears later in O’Day’s version, appears at the end of at least two other bridges: in Billy Strayhorn’s ‘Satin Doll’ (where it is sung with the lyrics ‘switch-a-rooney’) and in Alston and Tolbert’s ‘Hit That Jive Jack’ as sung by the Nat King Cole Trio, where it’s sung to the lyrics ‘da-di-ah-da’.

The bridge of ‘Miss Jones’ modulates through a series of keys which, like the bridge of ‘All The Things You Are’, is a challenge to any improviser. It seems that this is what has drawn many generations of jazz players to continue improvising on the tune’s changes. During the bridge, the speaker describes his reaction to meeting Miss Jones in a way that breaks romantic attraction down to a series of physical and mental sensations: (‘And all at once I lost my breath / and all at once was scared to death / and all at once I owned the earth and sky.’) It is typical of Rodgers and Hart’s gift for coordinating music and lyrics that this list of three symptoms, which move from mild physical distress to cosmic delusion, is accompanied by a modulation through three keys, Bb major, Gb major and D major, which are increasingly distant from the opening key of F major. (For another example of ingenious coordination of music and lyrics involving a similar progression, see the verse to the Rodgers and Hart tune ‘Glad To Be Unhappy’. One fine vocal version is this 1987 rendition by Carmen McRae.)

This bridge is sometimes mentioned as a possible inspiration for the chord progression of John Coltrane’s ‘Giant Steps’. Indeed, if one takes the chords from the first five bars of the bridge and removes the minor seventh chords – i.e. the Abm7 and Em7 chords – the remaining chords are the iconic first five chords of ‘Giant Steps’, just down a half step from the original key. (This less chord-laden progression is the way the bridge appears in the original sheet music and in versions by swing era players such as the one by Art Tatum and Ben Webster; the minor seventh chords were added by bop-influenced jazz players in versions such as the ones discussed below.)

In keeping with the song’s indirect approach to storytelling, the lyrics to the last eight bars imply that the speaker and Miss Jones strike up an ongoing relationship (‘we’ll keep on meeting till we die / Miss Jones and I’). As the song opens with a verse including a line that cryptically references marriage (‘the nearest moment that we marry is too late’), it seems that the speaker could mean he and Miss Jones get married, but there is room for multiple interpretations. (In the musical for which Rodgers and Hart originally wrote the song, I’d Rather Be Right, the couple referenced in the song do eventually get married, but that outcome is still uncertain at the point in the plot when the song is sung.)

The title of ‘The Missing Voice’ alludes to the fact that although we hear in the original lyrics from the protagonist and the unnamed introducer, Miss Jones herself never speaks. My melodic line, in keeping with bop tradition, is more active and chromatic than the original melody from which it borrows its chord progression. I imagine the lyrics to ‘The Missing Voice’ might be a more verbose counterpoint to the original melody’s long notes, something like Ethel Merman’s counterpoint to Donald O’Connor’s melody in Irving Berlin’s You’re Just In Love, or the bride’s anxious chatter in response to the clueless groom’s long notes in Stephen Sondheim’s Not Getting Married.

Stan Getz’s version of Have You Met Miss Jones from 1953 is one of the earlier versions to feature a medium swing tempo. This version also features Bob Brookmeyer on valve trombone and John Williams on piano (not the film composer, although he did spend time as a jazz player as well.) It is worth noting that this version was recorded in 1953, the same year as Tatum and Webster’s version. With the way that jazz history is often summarized as a progression of cleanly separated eras, it can be easy to miss that while the stylistic differences between swing era players like Tatum and bop-influenced players Getz originated in different eras, they were sometimes practiced concurrently as well.

Pianist Ellis Marsalis recorded the tune on his 1992 album Heart of Gold. During the first A section of his second chorus of solo on this version, Marsalis quotes the same fragment of ‘The British Grenadiers’ as Ella Fitzgerald uses in her 1947 ‘Lady Be Good’ solo. He also quotes Tiny Bradshaw’s ‘Jersey Bounce’ in the second A section of this chorus, Bud Powell’s solo on ‘Un Poco Loco’ in the last A section, and Mercer Ellington’s ‘Things Ain’t What They Used To Be’ in the third chorus. In his trading fours with drummer Billy HIggins on this version, Ray Brown quotes Billy Strayhorn’s ‘Rain Check’. (I discuss Ella’s ‘Lady Be Good’ solo in my post Ellavolution and ‘Rain Check’ in my post Emulate, Assimilate, Innovate Part 3.)

I like the Ellis Marsalis version a lot, it has nice voicings and I thought his solo was really good. I also like Anita O’Day’s version because she did interesting things with the rhythm of the melody and hers is different than other versions I’ve heard.

In the Stan Getz version, it feels like the melody gets muddied in all the other parts layered together. I didn’t exactly care for the sound of this version.