In a recent rehearsal of one of my student jazz ensembles, I asked a routine question of a student who hadn’t improvised yet: would they like to try taking an improvised solo by trading with one of the other players in the group? While the most common answers to this question are yes or no, this talented, articulate student answered in a way I hadn’t heard before: ‘I’m not sure,’ they said, ‘because I’m afraid I might run out of ideas’. This answer made me aware of how easy it might be for an improvised jazz solo to sound to the uninitiated like a non-stop flow of unique ideas with no repetition, and how easy it might be for these listeners to miss the places where great improvisers repeat their own ideas, adding ingenious innovations that transform their repeats into motivic development.

To illustrate the concept that great art can include repetition, this post will discuss Leonard Bernstein’s imagining of how a Shakespeare sonnet and a movement of Mozart symphony, both models of brevity, might have begun with longer first drafts. We will then move on to look at how T.S. Eliot’s poem Ash Wednesday and Charlie Parker’s solo on his tune Billie’s Bounce include both ‘first drafts’ and ‘revisions’ of short phrases. Both of these pieces use repetition as a way to move a story forward. As artist Peter Schmidt and composer/producer Brian Eno say in their Oblique Strategies, ‘repetition is a form of change’. While I think it is likely that Eno may have written this aphorism while thinking of the repetition in the world music he studies and incorporates into his own music, in which variation can be challenging to detect, this thought can apply in a different way to jazz improvisation. In a poem or a jazz solo, repetition with enough variation can become part of a narrative.

In his 1973 Harvard lecture on Musical Syntax, Leonard Bernstein quotes the opening line from a Shakespeare sonnet (‘Tired with all these, for restful death I cry’). He demonstrates how it can be elaborated into a longer, more prosaic version: ‘I am tired of life, so many aspects of life, that I would like to die – in fact, I cry for death – because death is restful, and would bring me release from all of life’s woes and injustices’. This is an example of the linguistic concept of ‘deep structure’. By comparison with Bernstein’s extended version of Shakespeare’s line, we can the line Shakespeare wrote (‘tired with all these, for restful death I cry’) as a poetic reduction which achieves more concentrated meaning through omitting additional explanation. Although the first line of this sonnet is a model of brevity, avoiding the kind of repetition shown in Bernstein’s imagined prosaic first draft, the poem itself includes significant repetition, although of a more abstract kind. The fourth through the sixth lines all follow the same sentence structure (adjective-noun-adverb-verb): ‘And purest faith unhappily forsworn / And gilded honour shamefully misplac’d, / And maiden virtue rudely strumpeted /And right perfection wrongfully disgrac’d.’

Bernstein goes on to explain how the opening of the first movement from Mozart’s Symphony no. 40 in G minor can be understood in a similar way. After a having the Boston Symphony play the first twenty measures of the movement as Mozart wrote them, Bernstein sets out to ‘invent or discover a deep structure out of which that marvelous surface structure [Mozart’s original version] has been generated’. Bernstein explains how Mozart’s opening eight bar phrase is a model of symmetry and starts to imagine a version of the piece where the introduction and the music that follows the first phrase mirror that symmetry. Bernstein then has the group play his own ‘deep structure’ version of the opening, which is more ‘prosaic’, symmetrical, and repetitious. Bernstein uses this example to demonstrate that part of Mozart’s genius is not just the strength of his ideas but how he deleted repetition that a lesser composer might have included. When the BSO plays Mozart’s original version in its entirety at the end of the lecture, the listener who has heard the ‘deep structure version’ can now hear the crafty concision of Mozart’s writing. Even though the original version avoids what Bernstein calls the ‘schoolboy repeats’ of his ‘deep structure’ version, one can see from how often Mozart revisits Eb-D-D motive that more moderate amd skillful repetition is still a prominent feature of the original.

While Bernstein imagines longer first drafts that Shakespeare and Mozart might have revised, T.S. Eliot’s poem ‘Ash Wednesday’ offers the reader a glimpse of the poet revising his own poem. The poem begins with three versions of the same line, each with a different length and a different meaning: ‘Because I do not hope to turn again / Because I do not hope/ Because I do not hope to turn.’ The opening ten-syllable line is condensed to the six-syllable second line, which is then expanded to the eight-syllable third line. In addition to these back-to-back alternates, Eliot continues creating variations on these lines throughout the poem. The second stanza has two variations on the third line (‘Because I do not hope to turn.’), separated by two intervening lines: ‘Because I do not hope to know’ and ‘Because I know I shall not know’. Later there are two other variations on the first line: ‘Because I cannot hope to turn again’ in the third stanza and ‘Because I do not hope to turn again’ in the fourth (I added italics to emphasize the altered words.) By writing his revision process into the poem, Eliot makes the constant journey back and forth between prosaic deep structure and poetic concision part of the story he tells.

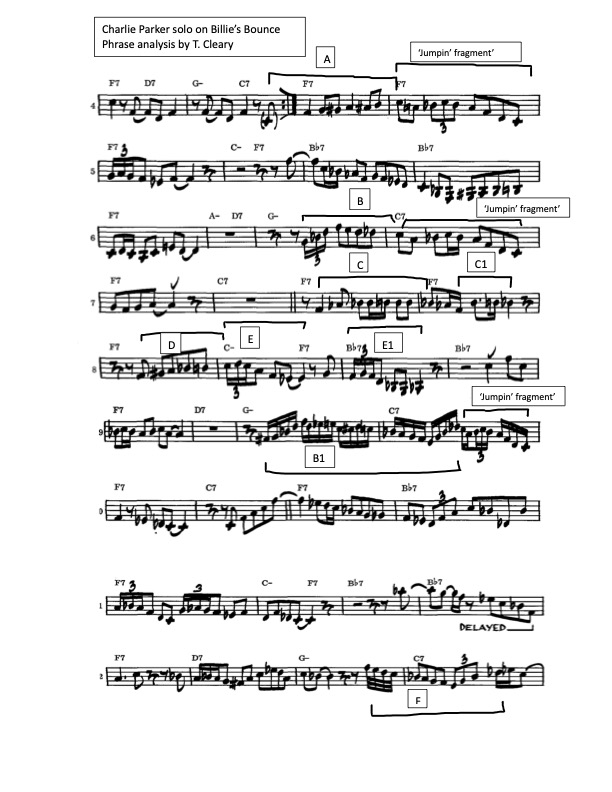

Charlie Parker goes through a similar process in his solo on ‘Billie’s Bounce’. (In the analysis that follows, please refer to the transcription below where I’ve labeled phrases alphabetically.) The kind of live revision that Eliot uses to open Ash Wednesday can be heard in Parker’s second chorus of solo: it begins with an eight-note pattern (C) which is followed by a four-note pattern (C1) that is a condensed version of the eight-note pattern. (Parker removes four notes between C and C1, the same number of syllables that Eliot removes between his first two lines.) This is followed by a six-note pattern (D) which is a condensed version of a seven-note lick that opens the solo (A). Like Eliot, Parker also revisits phrases to expand them. The six note lick in the fourth bar of the second chorus (E) is followed by a seven note lick (E1) that transposes and expands the preceding lick. The second chorus ends with a fusillade of sixteenth notes over the ii-V progression (the pattern marked B1 plus ‘The Jumpin’ fragment’) that is an expansion of the eighth note lick at the end of the first chorus over the same progression (the pattern marked B in the third system plus The Jumpin’ fragment).

In part two of this post, we will look at Erena Terakubo’s solo on the Jackie McLean blues ‘Bird Lives’ to see how a modern player can creatively incorporate Parker’s melodic phrases into their own vocabulary and adopt the musical syntax he uses to organize those phrases in an improvised solo.

©2025 Tom Cleary