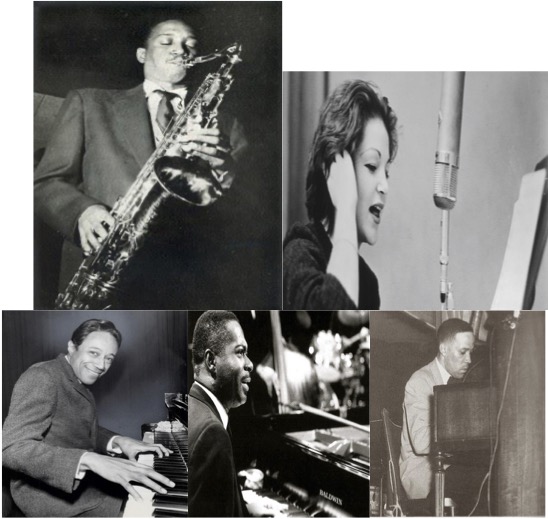

pictures clockwise from upper left: Wardell Gray, Annie Ross, Bobby Tucker, Hansel and Gretel, Wynton Kelly, Horace Silver

After you read this post, including the section using Freytag’s Pyramid to analyze ‘Twisted’, I encourage you to add a comment in the comment section analyzing the Horace Silver, Wynton Kelly or Bobby Tucker solos, or another improvised solo of your choice, in terms of how the solo either follows the rising action/climax/falling action structure, or reorders those stages somehow, adds other stages, or follows a different narrative structure through its melodic line and musical choices.

When I listen to an improvised solo, particularly a solo that follows a statement of a melody and uses the same chord changes as that melody, or improvise such a solo myself, I sometimes find it helpful to begin by asking, ‘why do they (or I) need to improvise?’ In other words, what is the strategy in this performance for spontaneously creating something different from the melody? In the case of a tune like ‘Blues By Five’, discussed in an earlier blog post, the simplicity of the melody gives a soloist one goal right away: to improvise something somewhat more elaborate and less repetitive than the head. After I’ve heard someone improvise once through the progression (or listened to myself doing the same), an important next question is ‘why take a second chorus?’ What would I as a player (or a soloist I’m listening to) like to have happen in a second chorus of solo that didn’t happen in the first chorus? One can also ask as a listener or a player how a third chorus will contrast with the second, and so on.

A good exercise to practice which can help develop one’s own answers to these questions is to learn a three-chorus blues solo by a great jazz player. Among the many values of this exercise are that one can incorporate phrases from the solo into one’s own vocabulary, and one can use the storytelling structure of that solo to inform an improvised solo. (See below for more on how storytelling structure can be found and created in both verbal stories and improvised jazz solos.) Playing a transcribed and/or improvised three-chorus solo on the twelve bar blues form is also an important exercise for aspiring improvisers as it allows them to create a performance where the amount of either previously or currently improvised material in the solo is either equal to or greater than the amount of composed material in the head (depending on how many times the head is repeated.) It is an unwritten but important guideline that jazz performers need to be able to give this kind of performance.

The following examples show a number of ways to create a continually evolving melodic ‘story’ in a three chorus solo on the ‘jazz blues’ progression. As the solos I discuss below demonstrate, among the ways soloists can create contrast within a three chorus solo are by gradually increasing their use of the higher range of their instrument, by introducing new thematic material in each chorus (in two of the four solos discussed below, this is done through the use of melodic quotation), and by using contrasting playing techniques, such as single note melodic lines and double notes of various intervals.

‘Twisted’ is a composition by tenor saxophonist Wardell Gray, who recorded his original version in 1949 with a distinctive three-chorus solo. In Gray’s original version, his solo was followed by a two chorus piano solo by Al Haig (which quotes Bud Powell’s Buzzy solo, discussed in an earlier post), a one chorus bass solo and another chorus of tenor before a return to the head. ‘Twisted’ began its journey toward becoming a vocal jazz standard when vocalist Annie Ross recorded a version with her own lyrics. In this version, Ross sings the head and the solo in Gray’s original key of Bb, followed by only one chorus of organ comping, which makes Gray’s solo as sung by Ross the sole focus of the performance. Ross also recorded a version with the trio Lambert, Hendricks and Ross, in which the key was changed to C and which her partners in the trio, Jon Hendricks and Dave Lambert, added distracting interjections.

Following Ross’ success with the song, it was also covered by following generations of singers with widely varying interpretations. Two versions were recorded in 1973: Bette Midler (with her then-music director Barry Manilow on piano) made it an overheated theater piece, and Joni Mitchell (with Cheech and Chong doing the interjections) made it a feminist statement, dialing up the coolness in Ross’s female patient responding to a fatalistic male psychologist. Although Mitchell is more faithful than Midler to Gray’s melody line, a version by jazz singer Jane Monheit in 2000, with a stellar band led by Kenny Barron on piano, is more swinging and more faithful to Gray’s original melody line than either Midler or Mitchell. The three versions together make ‘Twisted’ perhaps the best-known three chorus solo on the ‘jazz blues’ progression. My own personal encounter with the tune occurred in the late 1980s/early 1990s, when I was introduced to it by Archie Shepp as a student in his improvisation class. As filmmaker Abraham Ravett relates, Wardell Gray’s style on the saxophone had a significant influence on Shepp’s playing. I also played ‘Twisted’ on some of the first gigs I had accompanying jazz singers.

An important element in Gray’s solo on ‘Twisted’ are sizeable quotes from composed tunes and improvised solos by Charlie Parker that appeared in the years closely preceding Gray’s recording, as well as a quote from a pop song which Parker himself had quoted. The quotes make sense given that Gray played with Parker in the period preceding ‘Twisted’; he appears on the 1947 Los Angeles studio session that produced Parker’s classic tune ‘Relaxin’ at Camarillo’. The skillful way Gray’s Parker quotes are integrated into a melodic whole in ‘Twisted’ show that during the time he played with Parker, he was studying Parker’s melodic vocabulary in considerable detail. Please click on the tiny superscript ‘1’ at the end of this sentence to see a footnote with more detail on the many places in ‘Twisted’ where Gray quotes Parker.1

Gray’s solo is anything but a random collection of Parker quotations. One of the ways he builds the solo is to use one of the highest notes in the solo’s tessitura, Bb5, with increasing frequency as the solo goes on. Gray uses this note once in the first chorus, four times in the second chorus, and six times in the third chorus. Gray also saves the solo’s highest note, C5, for the third chorus, which also contains the highest concentration of chromatic bop language. The first two choruses, although they quote Parker, are diatonic enough that they might pass as a Lester Young solo if they were played in his characteristic tone. The evolution of Gray’s melodic story, with its movement toward greater use of chromaticism and high notes, makes it possible for Ross’s lyrics to tell a verbal story that parallels the peaks and valleys of Gray’s musical story. (See below where I analyze these two stories by using a literary analysis tool and making an analogy to a different story with the same structure.)

Horace Silver’s three chorus solo on his 1955 blues Doodlin’ stays in a more limited range than Gray’s ‘Twisted’ solo, but Silver keeps his musical story moving by introducing new motives throughout the solo. Each chorus begins with a different two-bar riff, which always is varied in the third and fourth bars of the form rather than being repeated exactly. The fifth and sixth measures of Silver’s second chorus contain what sounds to me like a quote of Bud Powell’s ‘Wail’. The riff which gets developed the furthest is in the third chorus, where he plays essentially same the riff four times with variations on second, third and fourth times. In another blog post, I describe Silver’s quoting of another Bud Powell tune in his solo on ‘Silver’s Serenade’. Lambert, Hendricks and Ross also recorded a vocal version of ‘Doodlin’ which added lyrics to the composed melody and Silver’s solo. Once again, an evolving melodic story, this time built on evolving motives that stay in a more restricted range than that of ‘Twisted’, inspire an evolving lyrical story, this time about a restaurant patron who is also a compulsive cartoonist.

Wynton Kelly’s solo on Johnny Griffin’s 1956 recording of his blues Nice And Easy includes more use of left hand comping than Silver’s solo. Appropriately enough for an album titled ‘Introducing Johnny Griffin’, Griffin introduces himself with a dense, busy solo in which he builds great energy but gives himself little time to breathe. By contrast, Kelly, who had recorded his first album as a leader five years prior and had also appeared on many recordings as sideman, gives his solo a relaxed opening in which right hand phrases are framed by left hand chords. Where Griffin is ‘double timing’ or playing 16th notes by the fifth and sixth measures of his opening quotes, Kelly waits until the eighth bar of his first chorus to drop in one brief double-timed phrase.

One way Kelly creates contrast between his choruses is to vary the amount of double timing he uses in each chorus; he uses a half-measure (two beats) of double timing in the first chorus, three measures of double timing in the second chorus, and two measures of double timing in the last chorus. Another kind of contrast between the choruses is Kelly’s choices of playing techniques; while he improvises a single-note melodic line in his right hand for most of the first chorus, he opens the second chorus with double notes in the right hand where he elaborates a moving line with the lower voice beneath repeated notes in the top voice.

I first became aware of Bobby Tucker through his exquisite duet with Billie Holiday on ‘I Thought About You’. Tucker seems to have been one of those players like Ellis Larkins whose excellence as an accompanist led them to be overlooked by jazz listeners and historians in favor of pianists like Oscar Peterson who, despite being excellent accompanists, were known best for their work as a soloist and bandleader. ‘Sweetie‘, from Tucker’s only trio album, Too Tough, recorded in 1959, is the only instrumental recordings discussed here which, like Ross’ original ‘Twisted’ and the Lambert, Hendricks and Ross ‘Doodlin’, features a single three-chorus solo as the centerpiece of the performance. While Tucker’s solo may not be as technically accomplished as Gray’s or Kelly’s, it does follow the arc of Gray’s solo in visiting the higher end of the solo’s tessitura more and more frequently as the solo goes on. It also contrasts a more blues-based approach in the first and third choruses with a more ‘making the changes’ bebop approach in the second chorus.

The chord progression of ‘Sweetie’ is a variation on the progression commonly known as ‘Bird Blues’ because it appeared in a number of Parker’s compositions, the best known being Blues for Alice. In place of the changes Parker uses in bar 7 of Blues for Alice (Am-D7), which becomes the second bar in a three-measure chain of descending half-step ii-V progressions, in bar 7 of ‘Sweetie’ Tucker uses an Ab major sixth chord, which creates a fourth complete major ii-V-I progression within the form (along with the ii-V-I progressions in D minor, Bb major and F major.)

The structure of a performance where a three-chorus solo is framed by a head in and out, such as Sweetie or the Ross’s versions of Twisted, can be compared to Freytag’s Pyramid, a tool developed in the early 20th century by novelist and critic Gustav Freytag for analyzing story structure. Particularly in plots of Shakespeare plays such as Romeo and Juliet and short stories like Hansel and Gretel, Freytag finds a five-part structure. I hear both Gray’s melodic line and Ross’s lyrics in ‘Twisted’ following the pyramid structure

– exposition – an opening section of a story in which the essential situation is introduced that will lead to the action of the story. In Hansel and Gretel, this is the section where we meet two young children who live with a father who loves them and an abusive stepmother who wants to find a way to leave them stranded in the forest so they won’t be able to return. In ‘Twisted’, this is the ‘head in’, where Gray’s opening melody is introduced along with the chord progression that will form the basis of the solo, and Ross’s lyrics introduce her conflicts with her analyst.

– rising action – a section where tension and/or complexity begins to build. In Hansel and Gretel, this is the part of the story where the two children follow the father and stepmother into the forest, but secretly leave a trail of breadcrumbs in hopes it will help them return. Although the breadcrumbs are eaten by birds, they find a gingerbread house in the woods which initially looks enticing but turns out to be inhabited by an evil witch. In ‘Twisted’, this is Gray’s first chorus of solo where he quotes Parker’s literally rising solo opening, and where Ross begins to look back on her childhood and offer her own analysis of it.

– climax – a section where the rising action leads to a culminating event of some kind. In Hansel and Gretel, this is the scene where Gretel pushes the witch into the oven that the witch had planned to use to cook Hansel. In the story, this grisly action allows Hansel and Gretel to escape the house, taking the witch’s collections of ‘pearls and precious stones’ with them. In a jazz performance, this is where the soloist reaches the peak of the rising action in the solo, which can be a process of rising in pitch, but can also be a peak of another kind; a peak of melodic density, through the use of shorter note values, or a change of playing technique, for example from single note playing to chordal playing on a chord instrument (as in Red Garland’s solo on Traneing In), or a change from solitary, monologue-style playing to a more conversational approach, either between a pianist’s two hands (as in Wynton Kelly’s solo on Four On Six), or between two ranges of a player’s instrument or between two different instruments (as in the second half of Clark Terry’s solo on Blues for Smedley – I discuss the first half in my post Summer Comping Trip), or between two players (as in Sonny Rollins’ solo on Tenor Madness.) The climax of the story in Ross’s lyrics is in the second chorus when she drinks ‘a fifth of vodka one night’, which leads her to develop an original idea and contradict her psychologist. The climax of Gray’s solo occurs later, at the beginning of the third chorus, when he unleashes the solo’s longest string of recurring high notes (he plays Bb4 six times in the course of three bars.)

– falling action – a section where, following the turning point of the climax, the fate of threatened characters is reversed, and/or questions may be answered, and healing may begin. In Hansel and Gretel, this is the children’s journey home, where they cross a body of water that initially seems impassable with the assistance of a duck. In Gray’s solo, this is the end of his third chorus, where he descends through the series of four Parker quotes described above to the Bb3 where the solo began, and this is the place where Ross’s lyrics describe the theory inspired by her childhood precociousness: that double decker buses are unsafe ‘because they had no driver on the top’.

– denouement / resolution – a section where the story comes of a place of fulfillment, ties up loose ends, and we may find out something about the ultimate fate of some characters. In Hansel and Gretel, this is where the children return home, find their father still alive having survived the evil stepmother’s death, and live happily ever after. In ‘Twisted’, this is the return to the head (or ‘head out’), where Gray returns to the composed melody with which he began, and Ross’ lyrics relate how she turns his analysis back on him (‘my analyst told me that I was right out of my head / but I said dear Doctor, I think that it’s you instead’) and concludes that what he sees as her neurosis, she sees as a superpower (‘instead of one head, I got two / and you know two heads are better than one’).

Ross’s lyrics have more than one kind of feminist resonance. They tell the story of a woman debating a male psychologist during psychoanalysis, a field that was still male-dominated in 1970, nearly two decades after Ross first recorded her lyrics to ‘Twisted’. In Ross’s lyrics, a woman’s experience in analysis becomes a journey of self-discovery when she takes control of her own narrative. It’s also notable that while Ross disagrees with her analyst’s diagnosis of her, he does act as a catalyst, because Ross does not dispense with the analyst during the song but rather makes her declaration of self-discovery during her conversation with him (‘but I said dear Doctor / I think that it’s you instead / ’cause I have got a thing that’s unique and new’…)

In the realm of jazz, Ross’ lyrics have also made it possible for many singers who might not have the opportunity otherwise to perform an extended improvisation. Because improvising is a pursuit that singers, and particularly female singers, have largely been excluded or discouraged from through most of jazz history, for many singers ‘Twisted’ may be the first (or even only) improvised solo that they perform. Ella Fitzgerald’s many adventures in extended improvisation, beginning with ‘Lady Be Good’ and ‘How High The Moon’ and continuing for the rest of her long career, are notable exceptions to this unwritten restriction, and have inspired many other great female improvisers. One example is Sarah Vaughan’s version of ‘How High’ from the album At Mister Kelly’s which directly references Fitzgerald. While a singer who is performing ‘Twisted’ is not improvising themselves, they are performing a transcription of a great improvised solo, a time-honored exercise in developing improvisational skill going back at least as far as Louis Armstrong’s solo on ‘Dippermouth Blues’. (In an earlier post, I discussed how Armstrong’s solo on ‘Dippermouth’ incorporated a solo by his employer and idol Joe ‘King’ Oliver.) While ‘Twisted’ has most often been sung by female vocalists, it can also be performed convincingly by singers of other genders, as a terrific version by tenor Thomas Owens demonstrates.

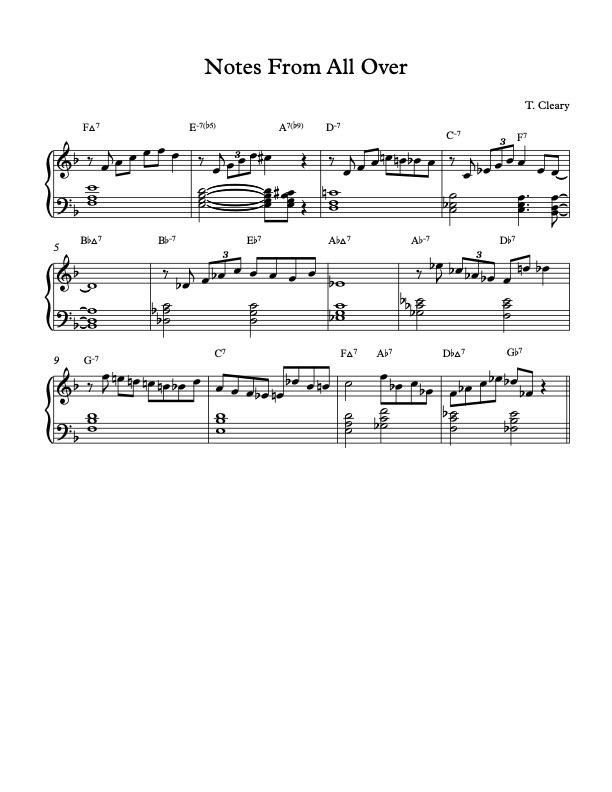

The chord progression of my tune ‘Notes From All Over‘ (please click on the title to see a keyboard video of the piece) is based on Tucker’s variation on the ‘Bird Blues’ progression. The title, which alludes to a recurring piece of marginalia in the New Yorker magazine, refers to the melody being borrowed from multiple sources, including the tune ‘I Can’t Get Started’, Elmo Hope’s ‘Later For You’, ‘I Thought About You’, Thelonious Monk’s ‘Round Midnight’, Miles Davis’s ‘Donna Lee’, Bud Powell’s ‘Strictly Confidential’, Clifford Brown’s solo on ‘Pent Up House’, and Horace Silver’s ‘The Jody Grind’. A number of these phrases appear in the Glossary of Melodic Patterns based on Root Position Chords (GoMPabRoPSevCho) introduced in the post with my tune Broken Heart For Sale. In these borrowings I’m using a technique which is used intermittently in Gray’s ‘Twisted’ solo, and almost constantly in Ella Fitzgerald’s solo on ‘Saint Louis Blues’ from ‘Ella in Rome: The Birthday Concert’, which I would call ‘allusive melody’. I follow this head with a three-chorus solo in which I attempt to demonstrate some of the concepts I’ve discussed in this post.

- Gray opens his solo by quoting the opening phrase from Parker’s solos on ‘Now’s The Time’ and ‘Billie’s Bounce‘, both recorded at the same session in 1945. This is the phrase that Ross sings on the lyrics ‘they say as a child I appeared a little bit wild’.

He opens his second chorus with a quote from the 1944 Bing Crosby song ‘Swinging On A Star‘ (from the film ‘Going My Way’). This is the phrase Ross sings with the lyrics ‘they say little children are supposed to sleep tight’. (Ross’s choice to make children the subject of her lyric here suggests she’s aware the source of Gray’s quote, as ‘Swinging On A Star’ is a song sung by Bing Crosby as Father O’Malley with his parish children’s choir in the film.) An excerpt from a live Parker solo on a Japanese website devoted to his quotes (albeit after Gray’s time with Parker) shows that this tune was also in Parker’s improvisational vocabulary.

In the ninth and tenth bars of this chorus (which Ross sings with the lyrics ‘do you think I was crazy?/ I may have been only three..’), Gray uses an altered quote from m. 15-16 of Miles Davis’s ‘Donna Lee’ (often credited to Parker), first recorded in May 1947. The connection to ‘Donna Lee’ makes this passage in ‘Twisted’ part of a chain of influence with four closely related links. The measures of ‘Donna Lee’ that Gray quotes show Davis making a slightly altered quote from a passage in Fats Navarro’s January 1947 solo on ‘Ice Freezes Red’. (Davis quotes from a number of other places in this solo as well, enough that Navarro’s solo could be called the template for Davis’ line.) In this passage, Navarro is in turn quoting the main motive from Fats Waller’s 1929 song ‘Honeysuckle Rose’. (As I hope to show in a future post, this was a melodic shape frequently reinvented by bop players.) Gray’s quote of ‘Donna Lee’ inserts space into Davis’s original lick. Navarro and Gray both use a reversal of the third and fourth notes of the ‘Honeysuckle Rose’ motive that appears in the second bar of Parker’s ‘Cool Blues’ (recorded shortly before ‘Donna Lee’ in February 1947). (The Parker discography at jazzdisco.com shows Parker performed ‘Cool Blues’ with Navarro in 1950 and Gray in 1951. Although both these dates are after the recording of ‘Ice Freezes Red’ and ‘Twisted’, it is possible that Navarro and Gray played it with Parker before these dates. The seventh bar of the head to ‘Twisted’ (where Ross sings ‘I knew all along’) could be also described as a pared-down quote of the first half of the ‘Cool Blues’ riff.

After opening the third chorus with the longest series of high concert B flats in the solo (five in the course of two measures) and following that up with the solo’s highest note in the eighth bar of the chorus, Gray closes the third chorus with what could be described as four Parker quotes or allusions in the course of four measures. Measure 9 (where Ross’ lyrics are ‘soldiers let them laugh at me’, misprinted as ‘soldiers used to laugh at me’ in some charts) can be heard as a paraphrase of the eight-note lick from bar 9 of Parker’s ‘Billie’s Bounce’ solo. Measure 10 begins with the variant of the four-note ‘Honeysuckle Rose’ motive found in measure two of ‘Cool Blues’. Measure 11 begins with the first four notes and the accompanying melodic rhythm from measure one of ‘Cool Blues’. The phrase that begins on the ‘and’ of 1 in m. 12 (‘there was no driver on the top’) is notated in the Sher fake book chart as a note-for-note quote of the first seven notes from Parker’s ‘Scrapple From The Apple’, and it is sung this way by Monheit, who makes it sound very natural. In Gray’s original solo, the opening note is more ghosted, i.e. played sotto voce in the interest of swing feel, and the fourth to last note is a concert Db rather than a C. The interval Ross sings on ‘there was’ in this phrase is closer a whole step rather than a half step; still, in both cases, the reference back to Parker’s motive is clear to my ear.

Gray was one of a number of jazz composers who anthologized Parker’s phrases in their melodic lines. He was preceded by Benny Harris, whose tune ‘Ornithology’ (often attributed solely to Parker, but which I argue in another post is more likely Harris’s composition) was recorded by Parker in 1946. He was followed by composers including Charles Mingus (‘Reincarnation of a Lovebird’), Freddie Hubbard (‘Birdlike’) and Steve Davis (‘Bird Lives’). In the way the strength of his melodic ideas inspires improvisers and composers to quote and innovate on them, Parker is something like a Shakespeare of jazz. Although there is an ongoing debate about exactly how many words and phrases Shakespeare contributed to the English language, a recent mention in The Writer’s Almanac credits him with inventing more than 3.000 words, and there are many partial lists like this one by Google Arts & Culture of phrases he is credited with originating. There are many similar lists of Parker’s phrases, including the website charlieparkerlicks.com that will transpose the lick for you through a sequence of your choice. A more exhaustive list is in the recent book and app Pathways to Parker, which catalogs more than 2,000 patterns (although some of the ‘patterns’ are only one or two notes). . ↩︎

this post copyright 2024 Thomas G. Cleary

Following a busy and complex solo from Johnny Griffin, Kelly Wynton’s solo in “Nice and Easy beautifully contrasts it with a smooth and lyrical display of the 12-bar blues. In the first chorus of his solo, he establishes a bluesy and soulful feel. Rather than displaying complex technical motifs, Kelly chooses a more simplistic approach that floats on the groove for the listener to digest easily. Kelly goes into the second chorus by using the higher range of the piano and emphasizes building the melodic line from the first chorus. While developing and exploring his themes, he begins to introduce his strong sense of swing, effortlessly riding the groove and vibe of “Nice and Easy”. He increases the use of double-timed phrases, adding to the rising action of his solo. In his last chorus, Kelly changes from using lots of double-timed phrases to using lots of repeating phrases, this helps the solo have a sense of conclusion and resolution to the story Kelly created. While not following a strict narrative structure by not having a traditional climax, Kelly will introduce a motif, develop it, and then bring this motif to a resolution. Missing this climax does not lessen the impact of Wynton Kelly’s solo, but creates a rich and engaging musical story within the context of “Nice and Easy”.

Joni Mitchell’s rendition of Twisted is indeed traditional as you mention here, but I did find the magic in it. Her vocal timbre differs greatly from the way she may sing Big Yellow Taxi for example. It is light, energetic, and leaves a lot of potential space for her to elevate the dynamics in the Head Out, which she does up until the slide on “one” before the fill that closes out the piece.

As a vocalist, not only do I find this timbre more suited to Gray’s composition, but I think it is a huge breathsaver for such fast runs at 140bpm. The way she jumps seamlessly into her falsetto, especially when she sings “…but I was swinging” and “…didn’t know what to dooo” which sets her version apart from those with baritone vocalists. She uses a slight vibrato that comes naturally with the swing and suits the upbeat nature of the tune. She is very much in tune with the walking bass beneath her in the head out, and moves in mostly parallel motion with that line, or the bass moves parallel with her…Whichever came first!

The most distinct observation I made while listening to “Twisted” was the way Mitchell interpreted how desperately these lyrics need to be said. Some jazz singers may take their time if a tune is about the journey and not the destination, but not here. Throughout the entire tune, you can hear each and every one of her big, gulping breaths. It adds a lot of character to her rendition because they are very infrequent even for a skilled vocalist. She takes a big, audible breath in order to go on and on through the verse. It really drew me in never having heard the tune before…”What did your analyst tell you?”

https://youtu.be/olyFmfqXxKw?si=Hr9Fhg6q8uNhes8X

In Jane Monheit’s rendition of “Twisted”, the sax solo at 2:19 fairly closely follows the piano’s rhythm, a straightforward quarter note drive which the drums emulate as well. This rhythm makes for a great build up/rising action to measure five, when all instruments deviate from this “quarter note drive” and opt for a more “swingin’” feel that appears to be a falling action precursor to measures 12-16. In measure 16, Lewis Nash hits some successive eighth note triplets on the snare and cymbals as the sax (I believe it is Hank Crawford, the alto saxophonist) hits a sustained note, which signifies a climactic section in the solo. This is followed by a melodic descent near the end of measure 16 and a significant high note after Nash’s crash on the first note of measure 17. Measures 16-17 could be considered the climax of the solo, followed by a falling action in measures 18-24.

As described in the post, Johnny Griffin’s densely constructed solo contrasts Wynton Kelly’s more laid-back and relaxed approach to a solo, fitting for a song titled ‘Nice and Easy’. When listening to Kelly’s solo while looking at Freytag’s Pyramid, it’s clear that Kelly loosely tracks the same thematic arc. First, he introduces a simple blues-inspired phrase that resolves itself, leaving much more space than the previous soloist. Then he introduces a simple phrase that he repeats twice, building complexity with the end of the second repetition by straying from just a single note playing. After these phrases, the rising action starts to emerge with the introduction of a 16th note line that ends the first chorus, giving the listener a taste of the more complex, dynamic, and fast second chorus to come. When he starts the second chorus we hear a louder blues line in a higher range that is followed by multiple quick 16th-note/triplet lines, defining the second chorus but still using space which doesn’t signal a climax quite yet. The climax is introduced a couple bars into the third chorus where he stays in a higher register for quite a while with repeating rhythmic intensity in the right hand that is finally released as he plays a 16th note run signaling the falling action into a not-so-well-defined resolution. Although Kelly is not following the pyramid structure to a tee, the outline is still there which goes to show how important this sense of story-structured improvising is when creating melodic phrasing that’s roughly based on the melody itself.

The first chorus of Horaces Silvers starts with single note blues lines with sparse left hand accompaniment. In the second chorus the melody line is now double stops involving the left hand more equally. There are still response notes from the left hand. The Final chorus, all hands are usually playing together for a chord melody approach. On the turnaround he goes back to single note blues lines. This is nice contrast before he starts comping.

Hi Bruno, Thanks for this well-described synopsis of the solo. Your comment about the end of Silver’s solo contrasting with the comping that follows reminds me of how his soloing is often organically related to his comping. For example, he begins his solos on Song For My Father, Sister Sadie and Cape Verdean Blues by using the comping figure from the head and improvising new melodic phrases in response to them.

While Wynton Kelly’s solo in Nice And Easy (Remastered 2006/Rudy Van Gelder Edition) may not exactly follow Freytag’s Pyramid, I would argue that the solo works up to a climax between 2:47 and 2:54 in the recording. At the beginning of the solo, Kelly starts out with mostly single 1/8 notes in the right hand with minimal comping in the left hand. As the solo continues, Kelly begins to play two notes (in intervals of thirds) in the right hand and works his way up the piano octave wise. I think that the introduction of upper octave third intervals in the right hand at 2:17 could be considered the rising action as it hints at what Kelly expands upon more during the climax. During the climax, Kelly plays more of the thirds in the right hand in the upper octaves and repeats a rhythmic pattern twice in two different keys. Then, he works his way all the way back down (octave wise) to where he started the solo which I would consider the resolution.