The melody of Thelonious Monk’s blues Misterioso is based entirely on ascending major and minor sixths. For most of the tune, Monk maintains perpetual motion by building ascending sixths off ascending and descending three-note major and minor scales. The last phrase is a series of ascending sixths built off the notes of an ascending five-note F major scale. This two-level ascension, ending on the unstable 7th of the dominant I chord, has the sound of a question. Monk used Misterioso not only as a ‘head’ or theme to bookend melodic improvisation on its chord progression, but also as a ‘lick’ or motive in his improvised solos, including his solos on the original recording of Straight No Chaser (another of his blues compositions that focuses resolutely on a single melodic concept), a live 1963 version of Misterioso and his solo on Take 1 of Bags’ Groove from the Miles Davis album of the same name. Leave a comment in the comment section if you can find the timings in either of these Monk recordings where Monk quotes the melody of Misterioso in his improvised solo.

An example of taking Misterioso to the innovate level can be found in Fred Hersch’s solo on the tune from his recent duo version with Enrico Rava.

Other jazz standards with melodies that prominently feature the ascending major and minor sixth include Billy Strayhorn’s Take The A Train, which opens with ascending and descending major sixths in m. 1-2 that are quickly balanced with consecutive descending and ascending minor sixths in m. 6-7, and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ‘Surrey With The Fringe On Top’, which builds over its first six measures to an ascending major sixth. This can be clearly heard in the version by Sonny Rollins from the album Newk’s Time, in which he performs the tune as a duet with drummer Philly Joe Jones. The ascending sixths in both these tunes have a sense of optimism which is reflected in the lyrics. In Something To Live For, Walter Van de Leur quotes Strayhorn explaining that the tune’s lyrics – ‘You must take the A Train to get to Sugar Hill way up in Harlem’ – celebrate a subway line that had recently been constructed around the time of the tune’s composition. Although many vocal versions of ‘A Train’ substantially alter the melody, including those by Ellington singers Joya Sherill and Betty Roche, the version by Ella Fitzgerald with the Ellington Orchestra stays closest to the melody as published and instrumentally played (as usual and as with her versions of many tunes, Fitzgerald is dependably faithful to the composer’s intentions.) In Oscar Hammerstein’s lyrics to ‘Surrey’, a turn-of-the-century cowboy named Curly enthuses to a prospective date, Laurey, about a different mode of transportation: ‘Ducks and chicks and geese better hurry / when I take you out in the Surrey / When I take you out in the Surrey With The Fringe On Top’.

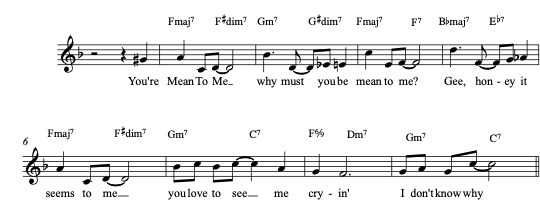

The disappointment felt by the speaker in the lyrics to the 1929 song ‘Mean To Me’ (‘Mean To Me / why must you be Mean To Me / gee, honey, it seems to me / you always leave me cryin’) is reflected in the repeated descending sixths of Fred E. Ahlert’s melody.

Ahlert’s descending sixths achieve the same effect as the signature descending tritone that punctuated the depressing punchlines of Rachel Dratch’s character Debbie Downer on Saturday Night Live. Ella Fitzgerald had an interesting history with ‘Mean To Me’ that seems to have begun in 1958 when she quoted an altered version of it as part of her solo on ‘St. Louis Blues’ from Ella in Rome: The Birthday Concert. The quotation appears in the ninth chorus of her solo, which begins with a quote from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ‘It Might As Well Be Spring’. In the ‘Mean To Me’ quotation Fitzgerald transposes the lower notes of Ahlert’s descending sixths up a diatonic third so that the descending sixths becomes descending fourths. Although it can be challenging to hear an echo of the original in Fitzgerald’s altered quote, Fitzgerald scholar Katchie Cartwright still identifies it as a Mean To Me quote in her article ” ‘Guess These People Wonder What I’m Singing’: Quotation and Reference In Ella’s Fitzgerald’s ‘St. Louis Blues’ “. To use Clark Terry’s term, Fitzgerald seems to have started her relationship with this tune in the ‘innovate’ stage.

One could say that Fitzgerald’s ‘assimilate’ stage with Mean To Me came during her iconic version of How High The Moon from the 1960 album Ella In Berlin. Fitzgerald’s 1960 solo reprises the three choruses of solo from her 1947 version, revises some of that material, and adds five more choruses as well as an extensive coda. One of the 1960 revisions is a phrase in the third chorus where she begins by quoting Duke Ellington’s Rockin’ In Rhythm as she did in the 1947 solo. In the earlier version this phrase stays well within the scope of four measures, but in the more athletic 1960 version, Fitzgerald continues this phrase past the fourth bar, ending with what is arguably a three-note quote of Mean To Me. Leave a comment in the comment section if you can identify the timing in the videos when either of these Mean To Me quotes appear (they are shortly after the timestamp to which the links lead).

One might say Fitzgerald reached the ’emulate’ stage with ‘Mean To Me’ when she made her first recorded version of the entire tune on Ella Swings Brightly With Nelson Riddle in 1961. On this version, she incorporates first the original form of the melody she briefly quotes in the 1960 How High The Moon, and shortly after, the alteration from her St. Louis Blues solo. While the musician’s axiom ‘fake it ’til you make it’ aptly describes Fitzgerald’s famous forgetting of the lyrics to Mack the Knife during her Berlin concert, which became one of her best-known and best-loved recordings, it would rarely if ever apply to her treatment of melodies, as she routinely learned melodies with great accuracy and based her variations on knowledge of the original, rather than improvising out of a need to fill in missing information. Her history with ‘Mean To Me’, on the other hand, might be summarized with a variation on that axiom: ‘quote it ’til you own it’.

Hi Prof. Cleary,

In the original recording of “Straight No Chaser” Monk quotes “Misterioso” at min 1:24-1:26.

In “Misterioso” Live from 1963 Monk quotes the melody at min 5:25-5:50.

Hello Prof. Cleary,

I find the usage of ascending and descending sixths across the pieces you mentioned interesting because they seem to have a very signature element about them that can really make a tune notable. I found the “Misterioso” quotes at 1:25-1:27 for “Straight No Chaser” and at 5:26-5:49 for the live 1963 version.

Hi Professor Cleary,

Another example of a song that prominently features the major and minor 6th is Fortunate Son by Creedence Clearwater Revival. The 6th interval can be heard in the song’s central guitar riff which first appears in the intro of the song. This riff features two ascending minor sixths followed by an ascending major sixth and finally an ascending perfect fifth, and this pattern is repeated many times throughout the song.