In 1947, the great jazz pianist and composer Bud Powell was sent to Creedmoor State Hospital, ‘one of the largest and most highly populated psychiatric facilities in New York State at the time’, writes Powell biographer Peter Pullman in Wail: The Life of Bud Powell. A story from that time indicates how challenging it is for any musician, and particularly one of Powell’s caliber, to be involuntarily confined without access to their instrument. Pullman writes that “a visit, which has been recounted in a number of printed sources, was supposed to have been made by [Powell’s friend and jazz pianist] Elmo Hope. The tale has Powell pointing to the wall above his hospital bed, where he had drawn some piano keys. ‘What do you think of this new tune that I’ve written?’ Powell supposedly asked, as his fingers struck the keys on the wall.”

Two years into his time at Creedmoor, on February 23, 1949, Powell was given a day pass to do his first recording session as a leader. Although Powell had had little access to a piano at Creedmoor, he had participated in a show performed at the institution by current inmates and community members called “The Rodeo Minstrel Revue of 1949”, an event for which Pullman writes that hospital administrators had ‘held up Powell’s release’. Pullman also deduces that Powell likely found a way to include some of his original tunes in the show, because when he arrived at the recording session he ‘came prepared with four original compositions…he had cleverly used his Minstrel Show rehearsal time to practice his repertoire and work on the improvisations.’ One of those original compositions was likely ‘Celia‘, dedicated to Powell’s daughter whose birth he was not able to attend, as she was born during his stay at Creedmoor. Pullman writes that ‘this hopeful, vernal melody had been composed during the previous year’s hellish incarceration.’ It seems likely, then, that ‘Celia’ may have been the tune that Powell silently played for Elmo Hope using the piano keys he drew on the wall of the institution.

The story of Powell drawing piano keys on the hospital wall and playing them is one of a number of accounts I’ve found of both professional and aspiring pianists drawing silent keyboards as a way of continuing to practice. A New Yorker article by Demetrius Cunningham describes his practicing on a homemade cardboard piano, which made it possible for him to become the accompanist for a prison choir. In a BBC profile, pianist Andrew Garrido tells of how practicing along with recordings on a paper piano got him through the first five grades of the Royal Academy of Music piano curriculum and began a career that eventually led him to study piano in a conservatory. In these times when the occasional need to quarantine is a fact of life, these stories remind us that musicians who find creative solutions through which they can continue practicing can both make the conditions they face a bit more bearable and move their musical progress in new directions.

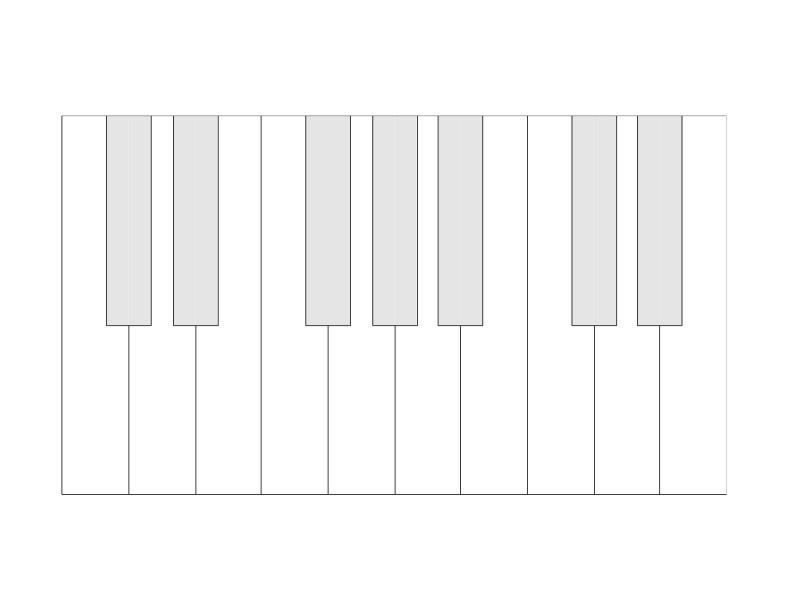

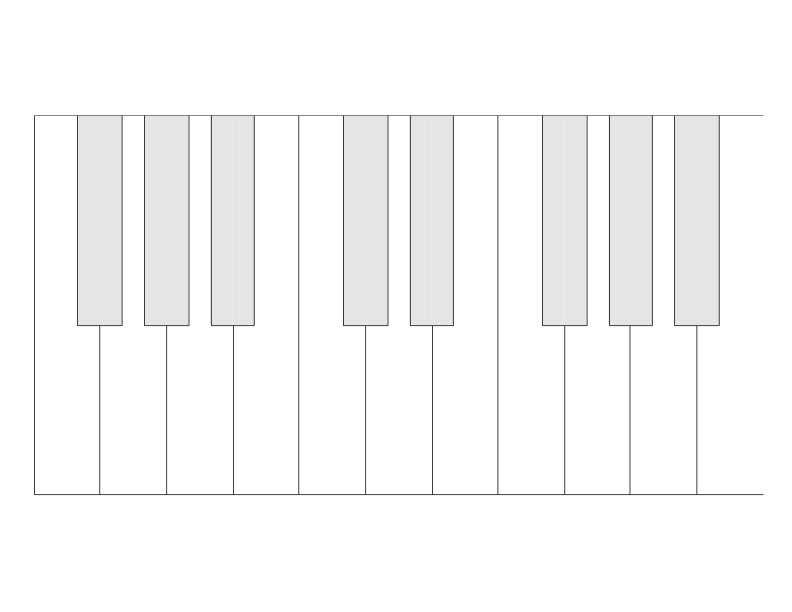

If you are quarantined without access to a piano or keyboard, but you have access to a printer, you could download and print out the two attached keyboard jpgs that can be found below. Fold over or cut off with scissors the left-hand 8 and 1/2 inch side of the jpg titled ‘Keys 2’ (the one with F on the left side) and attach it to the right-hand 8 and 1/2 inch side of Keys 1 (the jpg with C on the left side) with scotch tape if possible or masking tape on the upper and lower edges where the pages come together.

Another option is the Virtual Piano Keyboard at onlinepianist.com. On this keyboard, white keys C3 to E4 on the virtual keyboard correspond with the keys for letters Q,W,E,R,T,Y,U,I,O,P on the alphabetic keyboard. On the numeric keys, 2,3,5,6,7,9 and 0 correspond to the black keys for that range. The middle and lower rows of alphabetic keys correspond to black and white keys from F4 to Bb5. On Virtual Piano, the ‘sustain pedal’ (usually played with the right foot on an actual piano) is a button above the piano (next to buttons marked Letter Names and Keyboard Marks). The sustain pedal is automatically ‘on’ when the page loads, so you’ll need to click on this to turn it off (so it goes grey rather than white.) The sustain on Virtual Piano is an odd effect not really the same as the actual pedal. I recommend having Google metronome open in another window set to a slow tempo. If you turn on the Letter Names button on Virtual Piano, it will display letter names on the keys, which may be helpful. Navigating Virtual Piano via the QWERTY keyboard is quite different from navigating the piano keyboard, but it has enough similarities that it creates a useful virtual modeling of the keyboard. Here’s a video where I played one of the pieces from my beginning piano class on Virtual Piano.

Nice, I liked the anecdote about Powell. It’s amazing that he was able to compose entire pieces without an actual keyboard.

This reminded me a lot of when during the games Harmon from the Netflix show The Queens Gambit would visualize her games on the ceiling of the playing hall. Much like practicing piano I find myself being able to see my hands on the piano much like Beth Harmon can see chess.

Nice connection, Jonah! Here’s a link to a clip with some of the scenes where that happens:

https://youtu.be/b3uOClkoW2w?si=QzDlnRLTmgjPm8qi

I also thought of a scene called ‘Practice’ from the 1993 movie ‘Thirty two short films about Glenn Gould’ where pianist Glenn Gould, as played by Colm Feore, first describes the obstacles to practicing he encounters while on tour, as well as his dislike for some of the pianos he had to play in concert, after which he is shown mentally practicing the Allegretto from Beethoven’s ‘Tempest’ Sonata. The piano he hears in his mind sounds better than the ones he has to play!:

https://youtu.be/S_-HIQB1-qc?si=g68DO6v1MpPefRnl

In ‘Forty five seconds and a chair’, the Gould character is shown mentally practicing Bach’s two part invention in A minor:

https://youtu.be/3NzVEo27RBs?si=ieAO2SCvZqnpto5J

The fascinating scene ‘Truck Stop’ shows how Gould’s lifelong study of contrapuntal music influenced the way he heard human conversation and led him to create musical pieces where he layered multiple recordings of people speaking to create a kind of spoken-word parallel to musical counterpoint, where two independent melodic lines moving simultaneously create harmony:

https://youtu.be/UwIbqyihgg8?si=XhQ4I_-MQgN1nUjF