Recently I’ve been lucky to have connected with the great pianist and composer Bertha Hope. She has recorded three stunning albums as a leader, ‘In Search of Hope’ (1990) , ‘Elmo’s Fire’ (1991), and ‘Nothin’ But Love’ (1999). Her first husband was the legendary bop pianist Elmo Hope. Hope and his close friends Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell hung out and practiced so often together than they became known as ‘The Three Musketeers’, and while Hope is lesser known than Monk and Powell, his influence is continues to be heard in jazz today. Tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp dedicated a composition to him, and his music has been recorded by vocalist Roberta Gambarini as well as pianists Benny Green, Brad Mehldau and Tigran Hamasyan. As I mention in my blog post Musical Neighbors, I consider both Elmo and Bertha Hope to be part of the ‘Three Musketeers Collective’ along with Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk and Mary Lou Williams. Her second husband was the bassist Walter Booker, who plays bass on all of her albums; he died in 2006. Since then, Ms. Hope has continued to perform and compose, including a recent concert of Elmo Hope’s music at the Jazz Museum in Harlem.

I was also fortunate to have Bertha Hope work with my student jazz ensemble at UVM in an online coaching session this past spring. My group performed tunes by Ms. Hope including ‘Gone To See T’ (a tribute to Thelonious Monk), ‘Book’s Bok’ (which she mentioned includes her variation on the changes to Bobby Hebb’s ‘Sunny’, which I discuss in an earlier post) and Elmo Hope’s ‘De-Dah’. Here is a screen shot from the Q&A section of the workshop, taken while Bertha was in the process of answering a question by audience member Irene Choi, ‘What is jazz to you?’ As Irene remembers, Bertha’s answer began: ‘as Duke Ellington put it, ‘It Don’t Mean A Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing’. The picture captures some of the wonderful interaction in the workshop between the students’ inquisitiveness and Ms. Hope’s deep knowledge.

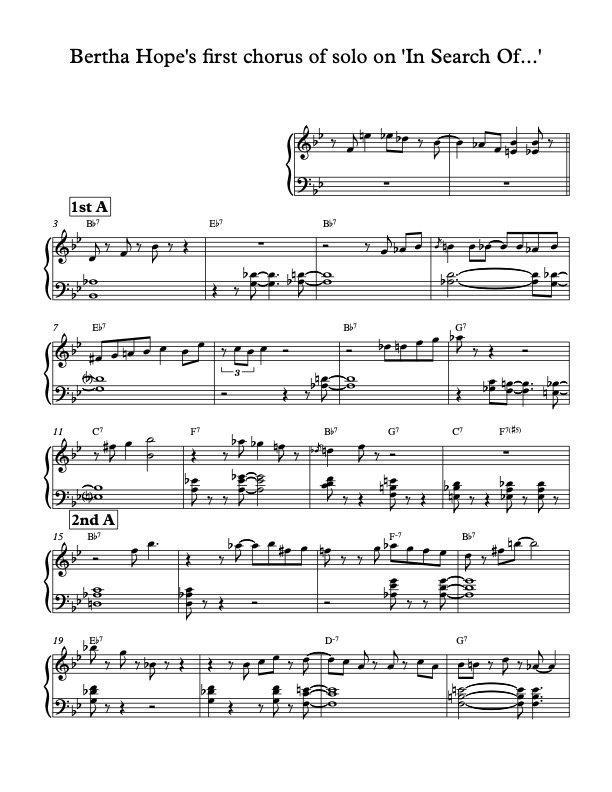

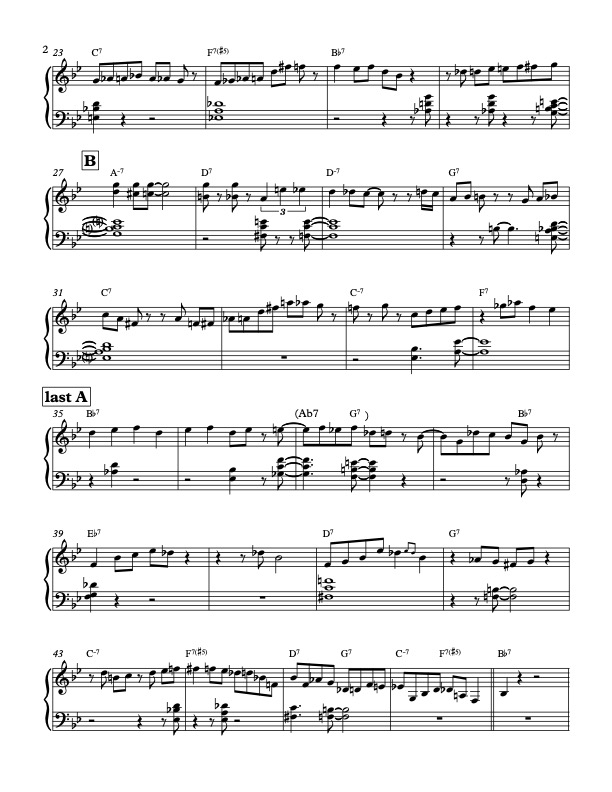

Before Ms. Hope worked with my combo, I transcribed her solo on the title tune from ‘In Search of Hope’, which she co-composed with Walter Booker. I find it to be a great example of what George Colligan terms ‘hand-to-hand conversation’. In an interview shortly before the workshop, I had the chance to ask Ms. Hope whether she thought carrying on a conversation between left-hand chordal comping and and right-hand melodic improvising. Her answers, transcribed below from our conversation, are an elegant demonstration in words of concepts that her solo demonstrates in music, including breathing, listening and taking time to shape phrases deliberately.

” [Pianist and educator] Ronnie Matthews said to me, ‘contrary to public belief, always let your right hand know what your left hand is doing’. You know the old saying ‘don’t let your left hand know what your right hand is doing’? [Perhaps the original source of this saying is the Gospel of Matthew Chapter 3, verses 6 and 5: ‘But when you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your alms may be in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you.’] Musically, that doesn’t work for the piano. You have to always let one hand inform the other, so that they’re engaged in a conversation. Sometimes there are blocked chords, you know, you play a chorus of locked hands, or a single line, and it’s kind of an internal conversation that you have with yourself, the two parts of the brain that are handling your fingers and all that information. And I think that’s what individualizes people’s playing. I don’t have any really hard and fast rules about it.”

I mentioned that a common challenge for developing and aspiring jazz pianists, particularly right-handed ones, is getting a conversation going between the left and right hands, because it is so easy for the right hand to take over.

Bertha continued, “And part of that is because they have so much to say! They’re so intense. You have to stop and think about breathing when you talk to people. While you’re listening, you’re breathing. Even inside of your own conversation, your own delivery, you have to take a breath. So breathing while you play, into your phrases, is a very important thing to try to get your students to manipulate while they’re learning how to improvise. Breathe! What is this next thing you want to say? Are you delivering run-on sentences that don’t go anywhere? Do you have something in mind about where you end and where you begin something else? Are you just so intense about keeping your hands on the keyboard that you play something that doesn’t have any real meaning, that doesn’t satisfy you enough so you keep going, keep going, keep going? So you have to stop and think about…just the way a singer has to stop and think about a meaningful breath so that the words have continuity. The instrumentalist has to think the same way.”