Many thanks to Professor Judith Tick, a music historian at Northeastern University, for providing the inspiration for this post. Most of the transcriptions shown here were commissioned as research assignments for her forthcoming biography of Ella Fitzgerald; the idea of a study of Fitzgerald’s improvising also came from her.

Note: This post includes many links to specific sections of recordings. To risk stating the obvious: after hearing each specific excerpt to which I have linked, it is crucial to go back and listen to the entire recording to hear the excerpt in context.

A common misperception of Ella Fitzgerald’s skill as an improviser is that she was essentially a gifted mimic who didn’t reach the artistic maturity of a Charlie Parker or a Roy Eldridge. ‘In mimicking virtuosity, she came to possess it’, wrote John McDonough in a commemorative Down Beat piece published three months after her death. Embedded in this quote is the widespread misunderstanding that Fitzgerald as an improviser was focused on mimicry as a means of displaying her own prodigious technique and so didn’t evolve to the level of melodic originality found in the improvising of great jazz players from the typical (and overwhelmingly male) pantheon. One of the main reasons for this misunderstanding is that Fitzgerald’s improvising has not been studied with anywhere near the same level of detail as, for example, the solos of Charlie Parker, which have been transcribed and re-transcribed by many generations of jazz players. Through transcribing many of Ella’s solos myself, collaborating with students on transcriptions of her solos, and studying the work of Fitzgerald scholars Katharine Cartwright and Justin Binek, I have found that rather than simply maintaining a knack for mimicry, Fitzgerald developed as a soloist over a long period of time through the three stages that trumpeter, educator, and Fitzgerald collaborator Clark Terry described as being crucial to the evolution of an improviser: ’emulate, assimilate, innovate’.

While Terry’s ordering of these three concepts suggests that they are consecutive steps where one stage leads to the next, Fitzgerald can sometimes be heard working on two of these stages at different points in the same solo. I have come up with definitions for each of Terry’s stages as they relate to Fitzgerald’s work as in improviser. In the ’emulate’ stage, in solos like ‘How High The Moon’ and the studio version of ‘Flying Home’, Fitzgerald is using borrowed melodic material in its original context, often in more extended excerpts. In the ‘assimilate’ stage, which can be heard in her versions of both ‘How High The Moon’ and ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ among others, she is using borrowed melodic phrases in a different music context than the one in which they originally appeared, stringing them together to create longer phrases of her own, and assimilating them into the solo by following them with her own melodic conclusions. Finally, in the ‘innovate’ stage, which becomes more prevalent in her solos from the late 1950s onward, she is performing a number of transformations on her melodic quotations, including singing them in inversion (upside down) (as in the trading with Stan Getz shown below). Other examples of the ‘innovate stage’ induce making multiple uses of the same melodic idea within a single solo where the lick is transposed to different keys and/or ‘chopped’ into different lengths (an example of the last two processes can be heard in her use of ‘The Irish Washewoman in her 1960 ‘How High The Moon’ solo which I discuss and link to in this post), and making repeated uses of the same lick with different rhythmic placements or followed by different material each time.

The iconic and dazzling scat solos on Fitzgerald’s 1947 recordings of ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ and ‘How High The Moon’ became set pieces which she re-used with only minor changes in live performances during the following decade, including a number which are available as live recordings. As I will show, both of the 1947 solos contain examples of Ella working through the ’emulate’ and ‘assimilate’ stages. After about a decade of performing the set piece solos, she began in some cases to radically expand on them, as in her 1960 version of ‘How High’ from ‘Ella in Berlin’, and in others to completely replace them with new and more improvised solos, such as her 1957 version of ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ from Ella Fitzgerald at The Opera House. This last recording, the first of the versions of ‘Oh, Lady’ listed in J. Wilfred Johnson’s ‘Ella Fitzgerald: An Annotated Discography’ where Fitzgerald does not repeat the 1947 solo, contains examples of the ‘innovate’ stage. In the 1957 solo, as well as many solos from later in her career, and especially in her solo on ‘C Jam Blues’ from Jazz at The Santa Monica Civic 1972, Fitzgerald can be heard more and more inhabiting the ‘innovate’ stage, demonstrating increasing spontaneity as an improviser and increasing skill with responding to creative opportunities presented in the moment.

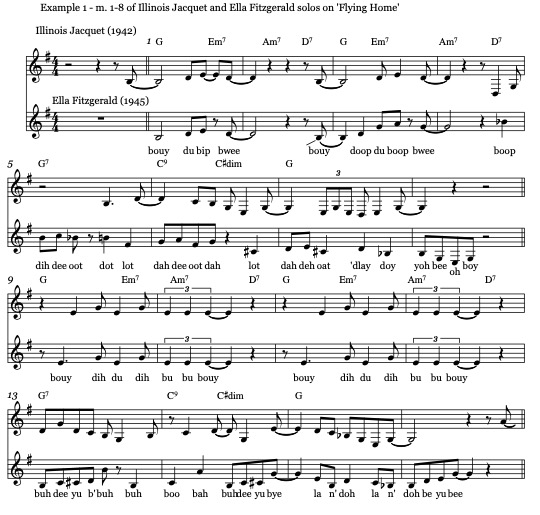

One of the earliest examples of Ella’s ’emulate’ stage can be heard in her 1945 re-creation of Illinois Jacquet’s 1942 ‘Flying Home’ solo. For most of the first chorus of this solo, she alternates between her own vocal interpretation of four bars from Jacquet’s solo and four bars of her own melodic ideas, essentially ‘trading fours’ with the immediate past.

Fitzgerald takes a similar approach in the first chorus of solo on her March 1947 recording of ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’. During this chorus she quotes in rapid succession the second strain of E.E. Bagley’s ‘National Emblem’ march (in the first A section of the tune), the opening of Rossini’s ‘William Tell Overture’ (in the second A) and the traditional folk tune ‘The British Grenadiers’ (in the last A section). In each case, she quotes four bars of her source material, followed by four bars of her own improvisation which creates a consequent phrase of her own to complement the borrowed antecedent phrase. (I discovered these quotes through studying Justin Binek’s excellent transcription of the 1947 ‘Lady Be Good’ solo in his paper ‘Ella Fitzgerald: syllabic choice in scat singing and her timbral syllabic development between 1944 and 1947.’)

A further development in her ’emulate’ stage can be heard in her December 1947 recording of ‘How High The Moon’ where her borrowings from the lesser-known trumpet player/composer Benny Harris are at one point more hidden and at another point more overt than her borrowings from Jacquet in ‘Flying Home’. Harris is not well known as a player, as he only briefly recorded as a sideman with Parker and Don Byas, and his solos on those sessions were rare and much shorter than those by the leaders. He is better known as the composer of a short list of tunes that have become bebop standards, including ‘Ornithology’, ‘Crazeology’, (a.k.a. ‘Bud’s Bubble’), ‘Reets and I’, and ‘Wahoo’. Although a number of published charts (such those in the Aebersold ‘All Bird’ book and the ‘Charlie Parker Omnibook’) credit Charlie Parker as the sole composer of ‘Ornithology’, a number of more recent sources (including the credits on a 2016 duo version by Brad Mehldau and Joshua Redman) identify Harris as a co-composer. (There is also an argument to be made, based on the chronology of Parker’s and Harris’s recordings, that Harris may have been the primary composer. For more on this, see my post on Ornithology.)

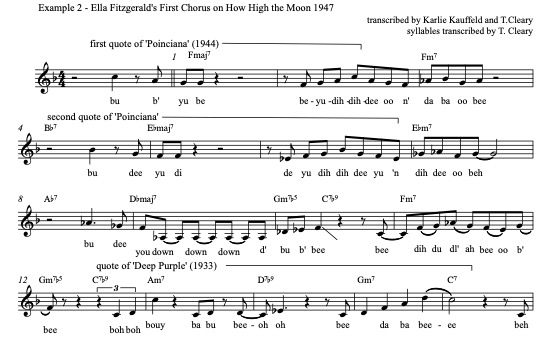

The first chorus of Fitzgerald’s 1947 solo on ‘How High’ (and her 1960 expansion of it on Ella in Berlin) includes a sign, clear and yet well embedded in the melodic line, that she was aware of Harris’s little-known work as an improviser. In m. 13-16 from the first chorus, she quotes the opening of Hoagy Carmichael’s ‘Deep Purple’, changing a few notes of the original but preserving the phrase’s overall shape.

It is very likely that she is borrowing here from Harris’ 1945 solo on ‘How High’ with Don Byas Quintet, where he uses the same fragment of the Carmichael tune at the same point in the form of ‘How High‘. In both solos she follows this with a more overt nod to Parker and Harris: a second chorus of solo which is a largely unaltered rendition of ‘Ornithology’. I consider both of these examples of the ’emulate’ stage, as she is using this material in its original context. Given the strong association the tune has with Parker, the quote reads as a tribute to him, but the more recent information about the tune’s authorship suggests that it is likely an instance of Fitzgerald borrowing from another borrower, Harris. After this initial extended use of ‘Ornithology’, Fitzgerald would go on to incorporate its opening motive as a piece of her melodic vocabulary, using it in the ’emulate’ stage in her 1957 ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ solo (where it is a repeated motive, as discussed later) and in her 1961 solo on ‘Perdido’ from Twelve Nights In Hollywood.

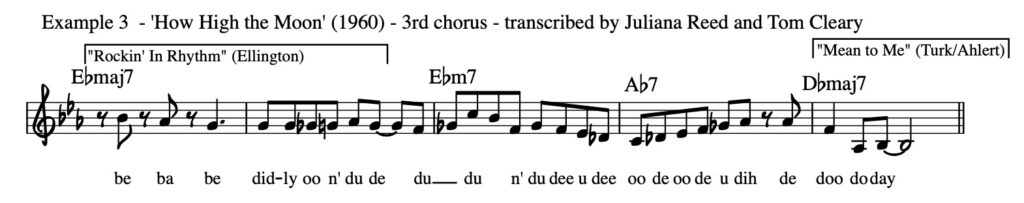

The ‘assimilate’ stage of Fitzgerald’s development as a soloist can be seen in sections of the 1947 and 1960 ‘How High’ solos and the 1947 ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ solo, where she incorporates back-to-back melodic quotations from multiple sources, as Harris frequently does in his solos on the Byas sessions. In these passages she is taking fragments from widely disparate melodic sources and assimilating them into a new harmonic context. A characteristic of these quotations is that while she typically follows them with a development of their melodic material or a phrase ending of her own, she usually does not repeat them or return to them later in the solo. The three borrowed phrases in the first chorus of the 1947 ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ solo mentioned earlier are examples of unrepeated quotes. The first choruses of the 1947 and 1960 ‘How High’ solos begin with a quotation from ‘Poinciana’ which is immediately transposed down a whole step to fit the ‘How High’ chord progression, but there are many more quotes that are used only once. These include, in both versions, the ‘Deep Purple’ quote in the first chorus and the quote from the opening of Ellington’s ‘Rockin’ In Rhythm’ in the third chorus.

In her 1960 version of ‘How High’, Fitzgerald expands the number of quotes used only once. While the third chorus still includes the quote from ‘Rockin’ in Rhythm’, in the 1960 version she concludes the phrase with a three-note quote of Turk and Ahlert’s ‘Mean to Me’.

‘Mean to Me’ appears in more than one Fitzgerald solo; her use of it in her ‘St. Louis Blues’ solo from two years earlier (from Ella in Rome: The Birthday Concert) reached the ‘innovate’ stage. Although her use of ‘Mean to Me’ in the ‘St. Louis Blues’ solo deftly alters the intervals and pitch direction of the original tune, Katharine Cartwright identifies it as a ‘Mean to Me’ quote in her transcription of the solo, a testament to Fitzgerald’s ability to transform a phrase and still give it an abstract but audible relationship to the original.

The six additional choruses that she adds in the 1960 version of ‘How High The Moon’ to the original three chorus solo from 1947 include quotes from the ‘Irish Washerwoman’ in the fifth chorus, the ‘Peanut Vendor’ quote in the sixth chorus, the ‘Stormy Weather’ quote in the seventh chorus, and the back-to-back quotes of ‘Did You Ever See A Dream Walking’, ‘A-Tisket, A-Tasket’, ‘Heat Wave’ and ‘The Grand Canyon Suite’ in the ninth chorus.

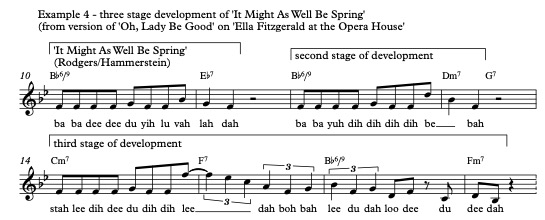

The examples I have found that illustrate Fitzgerald’s ‘innovate’ stage fall into three main categories. Earlier examples of the ‘innovate’ stage include solos in which she repeats a phrase three times back-to-back, adding motivic development on the second and third repetitions. The third iteration of the phrase is so altered that it becomes her own creation, a melodic idea whose connection to the phrase that inspired it would be untraceable if it didn’t appear immediately following the model phrase. This occurs in her 1948 solo on ‘Old Mother Hubbard’, which includes a three-stage development of the opening phrase from Ann Ronell’s ‘Willow Weep For Me’, and the first chorus of her 1957 ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ solo from At The Opera House, which features a development of the opening from ‘It Might As Well Be Spring’.

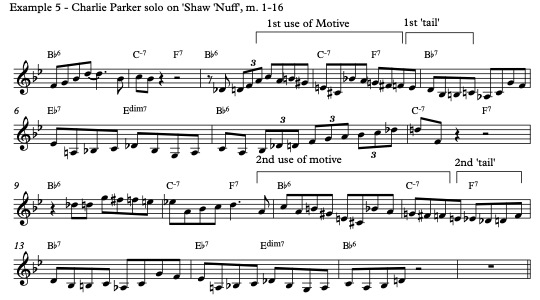

A second category of examples of the ‘innovate’ stage are situations where Fitzgerald develops a single motive at two different points in the same solo. This is a skill which Charlie Parker also exhibits in some of his most iconic solos. In his solo on ‘Shaw ‘Nuff’, Parker uses the same twelve-note motive twice in the space of sixteen measures, placing it on the upbeat to beat three in measure three the first time and on the upbeat to measure eleven the second time.

The five notes I have identified as the ‘first tail’ begin a four-measure phrase which is repeated (although with a shorter ending) at m. 13-16. Parker’s earlier placement of the motive in his second use of it necessitates the ‘second tail’, which becomes a connection to the repetition of m. 5-7. In m. 11-15, he adjusts the rhythmic placement of the motive introduced in m. 3-4. The earlier placement creates a space which he fills with the second tail before returning to the material from m. 5-6 in m. 13-14. I would argue that this kind of repetition and development of a single motive in separate sections of the form is one sign that a player is thinking about the solo from a more long-range, structural perspective.

Repetition of the same material in separate sections of the solo can also be heard in the 1957 solo on ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’. Other than a few references to the original, Ella’s solo on this version is a nearly complete departure from the 1947 version that she had been recreating in performances for a decade. Near the beginning of this solo, she sings the improvised lyrics: ‘I don’t know where I’m goin’ / but I’m goin’, I’m goin’…’, signaling her fellow musicians (and hip audience members) that she is in the midst of diverging from one of her most famous creations.

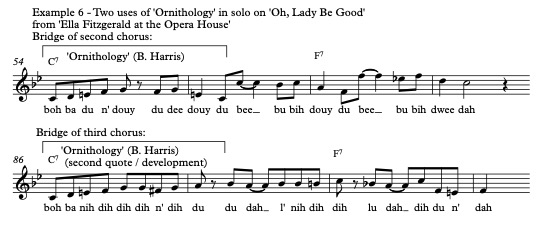

Fitzgerald finishes the bridge of the second chorus of this solo with a nine-note reference to ‘Ornithology’ that becomes a three-stage motivic development of its last five notes. She returns to this motive in the same section of the third chorus, finding a chromatic conclusion that contrasts the octave leaps with which she followed her first use of the phrase. This shows that in addition singing ‘Ornithology’ in its entirety for a number of years as part of her set piece solo on ‘How High’, she also used its opening motive as the basis of her own melodic developments.

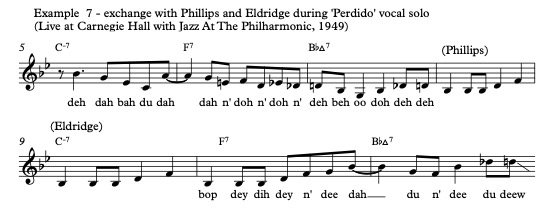

Another category of examples that illustrate the ‘innovate’ stage are situations in which she responds in mid-solo to melodic material improvised by other players between her phrases or, in some cases, ‘behind’ her phrases (i.e. concurrently with them). An early example of Ella’s ability to quickly react to melodic ideas encountered in mid-solo can be heard in her solo on Perdido from a 1949 live set with Jazz at the Philharmonic, a dazzling example of melodic grace under the pressure of a rowdy audience. During a two-bar break in her solo, a one-bar background line is played first by Flip Phillips and then by Roy Eldridge. In the following measure, Fitzgerald picks up the idea and expands it into a two-measure phrase. Here she is doing the same kind of expansion of a borrowed phrase that is heard throughout the ‘How High’ and ‘Lady Be Good’ solos that she performed so often, but doing it on the spur of the moment.

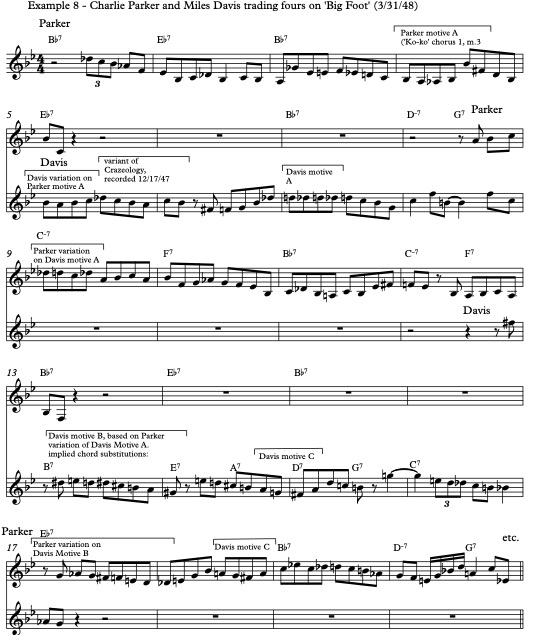

Another category of examples of the ‘innovate’ stage are performances where she trades two, four and sometimes eight bar phrases with other players. Fitzgerald often used these sections as opportunities to radically transform the ideas of other players and challenge her partners in musical conversation in ways that often showed her detailed knowledge of their instrument’s range and technique. Although instances of Charlie Parker ‘trading’ with other players are somewhat rare in his most iconic recordings, his trading with Miles Davis on ‘Big Foot’, a characteristic Parker blues line, shows this was a skill he also had evolved to a high level.

On the 1948 recording of ‘Big Foot’, Parker and Davis demonstrate highly evolved listening skills during a section of ‘trading fours’ that follows their individual solos. Each phrase in the trading is based on one and sometimes two ideas from the other player’s preceding four measures. Parker and Davis do not just emulate each other’s ideas but transform them in multiple ways, including subtly reshaping the melodic direction of the phrase and giving it a different rhythmic placement within the bar.

Near the end of his first four-measure phrase, Parker plays a six-note figure that he had played three years earlier near the opening of his iconic ‘Ko-Ko’ solo (I have marked this ‘Parker motive A’). ‘Ko-ko’ is based on the chord changes to ‘Cherokee’ and is in the same key (B flat major) as ‘Big Foot’. Davis begins his first four bars with a variant on the first four notes of Parker’s ‘Ko-ko’ phrase, followed by a minor-scale variant on ‘Crazeology‘, a tune he had recorded with Parker the previous year. In the third bar of his first phrase, Davis introduces a chromatic figure (‘Davis motive A’) which Parker then varies at the beginning of his next phrase. Davis begins his second phrase by playing the first four notes of Parker’s variation, transposed up a half step and moved one half beat later in the measure. Davis uses this as the opening of a line implying a series of chord substitutions involving dominant seventh chords moving around the circle of ascending fourths/descending fifths. Parker answers with his third phrase, a fourth-generation variant of ‘Davis Motive A’, by now refracted through three different variations he and Davis have made on it. In the second bar of his third phrase Parker re-uses what I call ‘Davis motive C’, a four-note connecting gesture. Parker repeats the notes of the motive, but moves it one beat earlier in the bar, a similar rhythmic shift to the one Davis made with Parker’s figure in his second four bars. A common theme through this trading section is bebop as a private or encoded language, with both players referencing melodic lines they had recorded in the recent past, as well as echoing each other but often using rhythmic shifts and transposition to make their source material less recognizable and put their own stamp on it.

Ella’s familiarity with Charlie Parker’s music is evident from the way that, after incorporating ‘Ornithology’ into the 1947 ‘How High’ solo (the ’emulate’ stage), she frequently incorporates smaller fragments from his melodic vocabulary into her solos (the ‘assimilate’ stage). In addition to the aforementioned ‘Ornithology’ quotes in the 1957 solo on ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ and the 1961 solo on ‘Perdido’, Fitzgerald quotes ‘Anthropology’ in her solo on ‘Flying Home’ from the 1949 Carnegie Hall Concert with Jazz At The Philharmonic (during which Parker can be heard playing fills behind her vocal) and at the end of a 1974 ‘C Jam Blues’ with a smaller group of JATP players that appears as ‘Conversation in Scat’ on YouTube. Just how closely Fitzgerald continued to study bebop melodic techniques and the level of mastery she attained in that style can be heard in her version of ‘C Jam Blues’ from the Jazz at the Santa Monica Civic 1972. This performance shows how her ability to spontaneously emulate, assimilate and innovate had continued to evolve since her improvising of the late 1940s and 50s, to the point where her exchanges with her musical interlocutors were on the level of the quasi-telepathy displayed by Parker and Davis on ‘Big Foot’.

Ella begins this performance with five choruses of solo on the C blues progression in which her trademark use of quotations is largely absent, other than a quote of the lesser known 1935 Gillespie/Parrish/Coots tune ‘Louisiana Fairytale’ in the second chorus and ‘Pop Goes The Weasel’ at the beginning of the third. For any listener who might have doubted it, this solo establishes her as a melodic creator with a level of originality on par with the imposing roster of soloists joining her on this tune, which includes trombonist Al Grey, tenor saxophonist Stan Getz, trumpeter Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison, tenor saxophonist Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis and trumpeter Roy Eldridge. Fitzgerald’s solo is followed with one by Al Grey, who displays prodigious technique and melodic vocabulary. Establishing a pattern that she will follow with the other soloists, Ella trades fours with Grey after his solo. Throughout this trading session, Ella sets a series of challenges for Grey in the execution of high notes, articulation of short notes, and even slide technique. Grey rises successfully to each challenge, including some phrases where his responses to Ella’s exhortations lead him to literally rise in pitch toward the limits of his instrument.

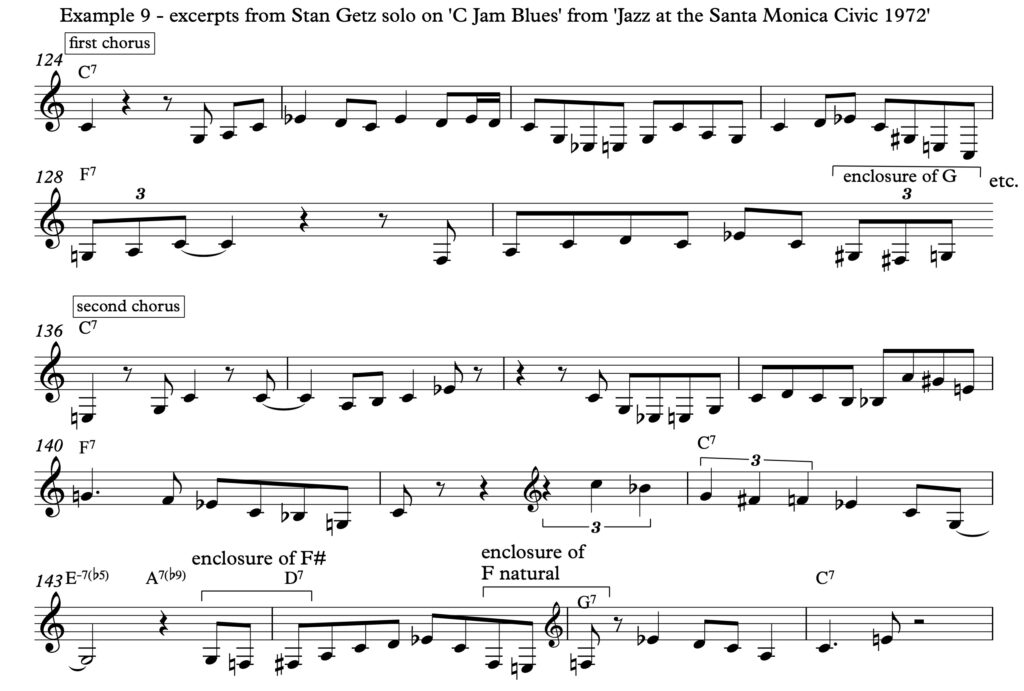

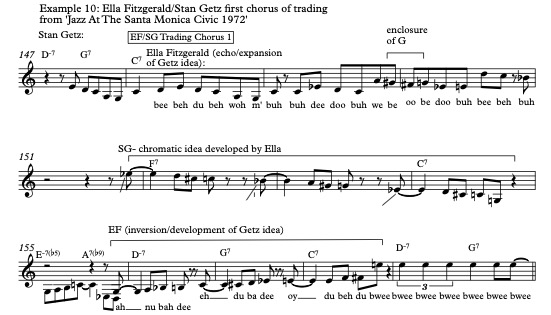

Following her trading with Grey, Fitzgerald melodically acknowledges him and introduces Stan Getz with the improvised lyrics ‘that was Al Grey wailin’ on the trombone…here comes Stan Getz’, interspersed with scat syllables. After Ella’s musical introduction there is a moment where she ’emulates’ a short Getz phrase and Getz ‘innovates’ by echoing her echo of his phrase but transposing it up to the C ‘blues scale’. Getz’ solo, which is largely a tribute to the swing-era tenor players who preceded him on the JATP stage, includes three instances of the common bebop device of enclosure, the chromatic ‘surrounding’ of a scale or chord tone with two chromatic upper and lower neighbor tones.

Throughout her trading with Getz that follows his solo, Fitzgerald signals her intent to move beyond emulating the ideas of other soloists and into developing and transforming those ideas, in other words, innovating. To adapt Clark Terry’s term, this might be called ‘innovate trading’. Fitzgerald begins the trading section with Getz at m. 148 by immediately echoing his closing phrase while adding an opening note to it (D). This is followed in the very next measure with a passage in which she uses the same notes as Getz’ first surrounding figure but moves it one half beat later in the measure – a rhythmic shift of the kind that Parker makes with the motive in ‘Shaw ‘Nuff’ and that Miles Davis makes with the Parker motive in ‘Big Foot’. Getz’s first phrase in the trading section is a four-bar phrase based on a four-note descending chromatic figure which he transposes down by a perfect fourth and then a fifth. The third time he states the four-note phrase, he adds a descending perfect fourth. Fitzgerald’s response to Getz’ chromatic phrase is to improvise an inverted (i.e., upside down) variation on it, complete with the concluding interval, now expanded to an ascending sixth.

Fitzgerald manages this complex maneuver with astonishing spontaneity, finishing by challenging Getz with a high E. The chromatic motive returns and is developed during Ella’s trading with Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison, climaxing in a phrase where she and Edison simultaneously play an expansion of the chromatic motive, leading to nearly a full chorus of Fitzgerald laughing.

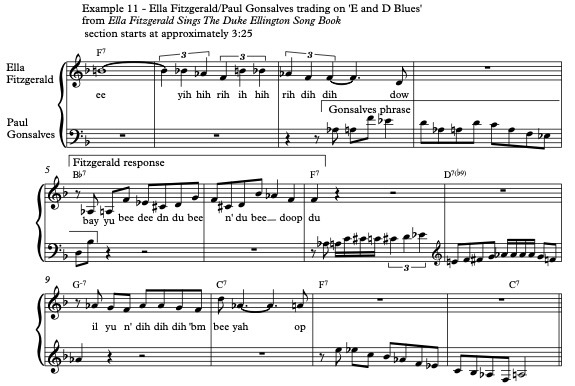

Another example of ‘innovate trading’ which also uses transposition but involves more motivic development can be found in Ella’s trading with Paul Gonsalves on ‘The E and D Blues’ from Ella Fitzgerald Sings The Duke Ellington Songbook. This is the last trading exchange of the tune, in which Ella begins her response to a Gonsalves phrase by echoing it and then performing a number of other transformations to it. Fitzgerald’s multi-layered motivic development of Gonsalves’ phrase is remarkable, considering that she is responding to a line that he began playing before she finished her previous phrase.

In the space of two measures, Fitzgerald moves Gonsalves’ phrase one beat earlier in the measure, echoes his first four notes, deletes his fifth note and moves the sixth, seventh and eighth notes up a perfect fourth, creating a kind of inversion of the phrase and forming a typical bebop enclosure of D4 that is not in Gonsalves’ more diatonic original. She ends her phrase by transposing his opening four-note motive up a perfect fourth.

‘Innovate trading’ could be contrasted with two other categories of phrases which Ella contributes to improvised conversations. I’ll define ’emulate trading’ as an echo of a preceding phrase by another improviser, often followed by material not directly related to the phrase being echoed. This can be heard elsewhere on Sings The Duke Ellington Songbook during her trading with Ben Webster on ‘Cottontail’ and on ‘E and D Blues’ in her trading with Johnny Hodges and Clark Terry that comes before the exchange with Gonsalves. There are also examples of what I would call ‘assimilate trading’, where Ella takes a small piece of a previous phrase, sometimes as few as two notes, and uses it to build a new phrase where her source material is less identifiable due to the economy with which she borrows. This can be heard during her trading with Tommy Flanagan on the version of ‘One Note Samba’ from the album ‘Montreux ’77’.

Ella’s evolution as a soloist demonstrates that ’emulate, assimilate, innovate’ are all stages through which great improvisers are constantly moving. The trading with Getz on ‘C Jam Blues’ from Jazz at the Santa Monica Civic, and on recordings from later in her career, show that rather than staying with established routines, Fitzgerald became increasingly daring, agile and innovative as a soloist in her later years. Along with the transformations that she works on material from other soloists and the long stretches of original melodic material that precede and follow these transformations, another sign of her increasing fearlessness and abandon is her choice of bebop tunes to quote. In versions of ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ from a Chicago TV performance in the 1970s and a live 1981 Edinburgh concert, she quotes Parker’s ‘Moose The Mooche’. More audacious is her quoting of ex-husband Ray Brown’s tune ‘Ray’s Idea’. While this tune was in her melodic vocabulary as early as 1947, when she quoted it in a Carnegie Hall version of ‘How High The Moon’ with Dizzy Gillespie that predates the studio version, she returned to it in her trading with Eddie Lockjaw Davis in the 1972 ‘C Jam Blues’ and in another filmed ‘C Jam Blues’ from the 1979 Montreux Jazz Festival with the Count Basie Orchestra (mislabeled as ‘A-Tisket, A-Tasket’.)

In the 1972 ‘C Jam’, her ‘Ray’s Idea’ quote sounds like a final twist on the chromatic motive introduced by Getz during the trading and transformed in the trading between Fitzgerald and Edison. In the 1979 ‘C Jam’, she effortlessly elides the first two bars of ‘Ray’s Idea’ with an improvised ascending scalar tail that she adds to the phrase. Both ‘Ray’s Idea’ and ‘Moose’ are less hospitable to vocal adaptation because of their complexity, chromaticism and wide tessitura. As compared to the fragment of ‘Ornithology’ she uses in the 1957 ‘Lady Be Good’, the ‘Moose The Mooche’ fragment covers the range of an eleventh and ‘Ray’s Idea’ covers an augmented eleventh. These tunes were even avoided by bop-oriented vocalists like Eddie Jefferson who recorded many Parker compositions. Kurt Elling, who within the current generation of jazz vocalists is one of the most agile at adapting complex instrumental tunes, recorded ‘Moose’ only recently, well into the third decade of his career. That challenging motives from these tunes became part of the regular vocabulary of Ella Fitzgerald’s improvisations in her later years is only one example of the many ways that, rather than resting on her substantial laurels, she was on a constant journey in search of new challenges and pathways to innovation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND DISCOGRAPHY

Binek, Justin Garrett. Ella Fitzgerald: syllabic choice in scat singing and her timbral syllabic development between 1944 and 1947.

Cartwright, Katharine. Guess These People Wonder What I’m Singing: Quotation and Reference in Ella Fitzgerald’s ‘St. Louis Blues’

Ellington, Duke. 1958. Ella Fitzgerald Sings The Duke Ellington Song Book. LP: Verve MG V-4008-2.

Fitzgerald, Ella. 1956. Lullabies of Birdland. LP: Decca DL 8149 (Includes 1947 studio versions of ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ and ‘How High The Moon’

Fitzgerald, Ella. 1959. Ella Fitzgerald at The Opera House. LP: Verve MG V-8264 (Includes 1957 Shrine Auditorium version of ‘Oh, Lady Be Good’.)

Fitzgerald, Ella. 1960. Ella In Berlin: Mack The Knife. LP: Verve MG V-4041 (includes 1960 ‘How High The Moon’)

Fitzgerald, Ella and Basie, Count. 1972. Jazz At The Santa Monica Civic 1972. LP: Pablo 2625 701 (includes ‘C Jam Blues’)

Fitzgerald, Ella. Ella in Rome: The Birthday Concert. LP: Verve 835 454

Gillespie, Dizzy. 1955. Groovin’ High Savoy MG 12020 (Includes ‘Shaw ‘Nuff’)

Johnson, J. Wilfred. 2001. Ella Fitzgerald: An Annotated Discography; Including a Complete Discography of Chick Webb. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: MacFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

McDonough, John. “Ella: A Voice We’ll Never Forget”. Down Beat: September 1996.

Parker, Charlie. 1990. Charlie Parker – Bird’s Eyes Vol. 1 Philology (It) 214 W 5 (Includes ‘Big Foot’.)

VIDEOS (YouTube)

‘Conversation In Scat’ – 1974 performance of ‘C Jam Blues’ – directed by Helmut Ros

‘Ella Fitzgerald & Count Basie – A Tisket A Tasket (Norman Granz Jazz In Montreux 1979) (actually a performance of C Jam Blues)- on Montreux Jazz Festival YouTube Channel

‘Ella Fitzgerald In Concert Edinburgh 1981’

‘Oh, Lady Be Good’ on Chicago TV station with Paul Smith Trio, Zoot Sims, and Roy Eldridge; probably 1983