On May 8, 1947, pianist Bud Powell made his only studio recording with Charlie Parker, at a time when the saxophonist’s fame as a soloist and bandleader had recently begun to rise. He had recorded with pianists including Dodo Marmarosa, Nat King Cole, Erroll Garner and Sadik Hakim, and had even used Dizzy Gillespie on piano at one point, but he had not yet done a recording session with Powell, who was becoming known as an erratic genius. As Peter Pullman notes in his biography Wail: The Life of Bud Powell, although Parker and Powell had worked together on and off since mid-1945, Powell did not show up for Parker’s first recording as a leader that same year, despite being the pianist in his working band, and had to be replaced by Hakim and Gillespie. Earlier that year, the pianist had missed his first opportunity to play with Parker in Cootie Williams’ band because Parker joined the band while Powell was on leave from it while being institutionalized in a series of psychiatric hospitals.

After the 1947 recording sessions, Parker and Powell would go on to play more live performances together where their odd-couple dynamic became increasingly clear on a musical level. As I mention in an earlier blog post, these performances, as heard on the albums One Night In Birdland and Jazz At Massey Hall, contain brilliant playing by both musicians, but also examples of how Powell’s idiosyncrasies as an accompanist threw Parker off his usual unshakeable balance. On both these recordings, Powell sometimes can be heard musically irritating Parker and in one case nearly derailing him with a confusing intro on ‘Ornithology’. Both Powell’s musical disruptions and Parker’s resistance to them are both ingenious, and the counterpoint between them is sometimes hilarious.

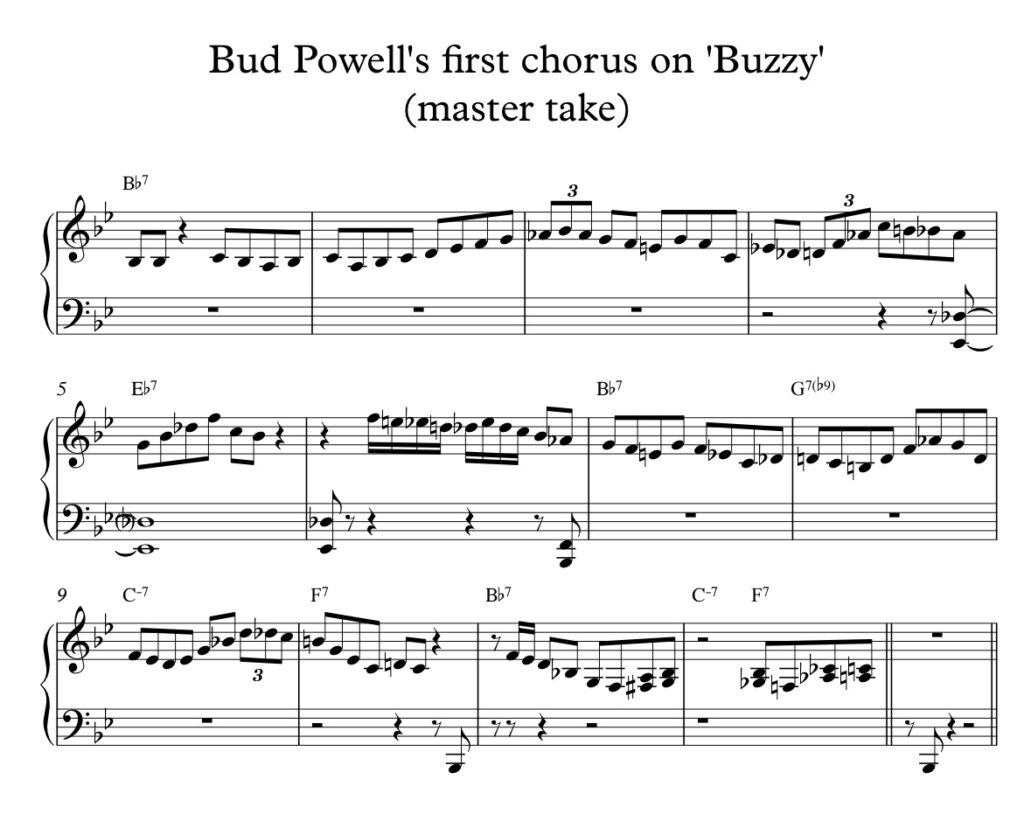

Pullman notes that at the May 1947 session, Powell is ‘not given much solo space on any of the takes’ – on what became the most famous recording from the session, Donna Lee, Powell is given only 16 bars to improvise – but that he ‘steals a chance to shine on “Buzzy“‘, one of the two Parker tunes from the session that use twelve-bar blues progressions. I would add that, despite what we know about the pressurized and possibly competitive atmosphere that makes it seem like Powell would need to ‘steal’ solo space in the recording, there are at least three places during the first twelve bars of Powell’s solo that show the deep connection he had with Davis and Parker through their shared melodic language.

In measure 5 of his solo from on the master take of Buzzy that was released as a single the same year, Powell deftly quotes a phrase from m. 3-4 of ‘Donna Lee’, the tune recorded at the beginning of the session. ‘Donna Lee’ is often attributed to Parker but is now credited in many accounts to Miles Davis (including in Davis’ 1989 autobiography, where he tells Quincy Troupe: ‘I wrote a tune for the album called “Donna Lee,” which was the first tune of mine that was ever recorded.’) It’s astonishing to consider that the recording session may have been the first time that Powell heard ‘Donna Lee’, and so it’s possible that this may be an example of Powell assimilating a new phrase into his melodic vocabulary at lightning speed.

Powell closes the first chorus of his ‘Buzzy’ solo with two uses of a figure that he may well have learned from Parker’s iconic ‘Koko’ solo. It first appears on beat four of m. 9, starting with a chromatic descent from D5 to B4. B4 then becomes the first note of a C major-minor seventh chord arpeggio that Powell uses to navigate the progression from Cm7 to F7. This is an innovation on the way Parker originally used the lick, which was to as a decoration of a major sixth chord arpeggio. Powell includes the lick in its original context as well before the end of the chorus, descending on the first three beats of m. 11 from F4 to F3, embellishing a Bb major 6th arpeggio on the way (although with diatonic scale steps rather than the chromatic movement seen in m. 9.)

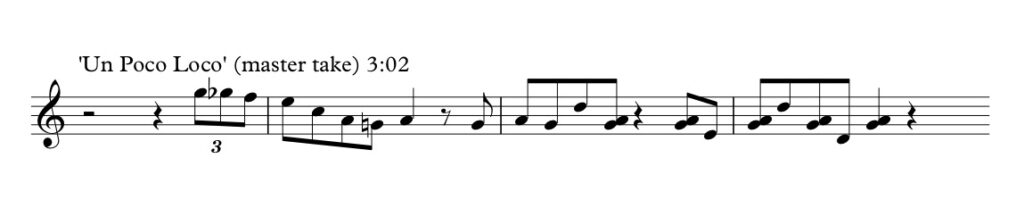

Powell would use a version of this lick that combined the chromatic beginning with a diatonic ending at the end of his iconic solo on Un Poco Loco four years later in May of 1951.

One possible origin story (or, one might say, creation myth) for this lick can be found in Parker’s iconic ‘Koko’ solo, recorded in 1945, released in 1946 and based on the chord changes to the jazz standard ‘Cherokee’. (I wrote about the history of this progression’s use in an earlier post, Tonight These Chords Belong To Me.) The influence this solo had on Parker’s contemporaries is suggested in an essay by music librarian Ed Komara published on on the Library of Congress website in 2003, when ‘Koko’ was added to the Library’s added National Recording Registry. Komara calls ‘Koko’ ‘Parker’s signature jazz piece’ and ‘ and ‘a call for musical revolution’. In the first chorus of his ‘Koko’ solo, six bars from the end of the bridge, Parker plays the lick that Powell was to use two years later in the same key at the end of his ‘Buzzy’ solo. The lick (which I’ll call ‘the Bird/Bud Koko lick’) can be seen in measure 75-76 of Remi Bolduc’s transcription of the solo, which Bolduc shows in a video that pairs his transcription with the audio of the ‘Koko’ recording (the lick and the relevant part of the transcription occurs just before 1:00 in the video). The ‘Bird/Bud Koko lick’ figures prominently in two solos on the ‘Cherokee’ progression that Powell recorded following his session with Parker, his 1949 trio version with Ray Brown and Max Roach from The Genius of Bud Powell (which, like ‘Koko’, opens with a dubious jazz impression of Native American drumming) and his 1957 trio version of ‘Koko’ from the fascinating and posthumously released ‘Bud Plays Bird’. (This album also includes Powell revisiting ‘Buzzy’ with his trio.) If you can find the timing for Powell’s use of the ‘Bird/Bud Koko lick’ in either of these recordings, I invite you to leave a comment in the comment section.

In July of 1951, in the same recording studio where Powell recorded Un Poco Loco two months earlier, a young Wynton Kelly did the first of two recording sessions that would become his first album as a leader, Piano Interpretations. In a 1963 interview where he gave a quick rundown of his recordings as a leader, Kelly referred to this album as ‘one I made in 1950 [sic] when I was 19 that doesn’t even count’, but it actually shows the beginnings of what would make Kelly a unique, pivotal and sought-after accompanist and soloist in mid-twentieth-century jazz. Kelly also pays tribute to Bud Powell in the interview, saying: “I respect Bud as one of the main figures in starting modern jazz piano.” In his version of Cherokee, Kelly begins his solo with a phrase very similar to the closing move from Powell’s ‘Buzzy’ solo. (The release date of ‘Buzzy’ makes it possible Kelly might have heard it before recording his version of ‘Cherokee’.) On his second use of the lick at 1:09, Kelly plays a chromatic version of Powell’s phrase (F-E-Eb-D-Bb-G) and adds his own tail (G-Gb-F-Eb). Kelly continues to return to the idea throughout the solo, never reproducing it exactly but working with shorter variants of it, playing it higher registers than Powell did, but in the same key.

While Kelly is working with many Bud Powell-inspired phrases in the right hand, his left hand alternates between compound-tenth voicings typical of Powell’s playing and the higher rootless voicings that would become a trademark of his sound in his work with Miles Davis. In comparison to the nearly non-stop right-hand monologue that Powell carried on in his solo on Serenade to A Square, which uses the Cherokee chord progression and which Kelly may have also heard, Kelly’s solo is distinctive and ground-breaking for its use of what George Colligan calls ‘hand to hand conversation’ to create space within his solo. Through taking a more conversational approach initiated by his left hand, Kelly introduces the crucial element of space, allowing the listener to hear Powell’s language in a new way – as one half of a conversation rather than a monologue.

It is a sign of how indispensable Kelly became as a sideman, as well as perhaps a clue about his personality, that he did not record another album as a leader (other than a session co-led with Lee Morgan) until the album Piano seven years later. In the interim, he recorded with a ‘who’s who’ of jazz soloists, most prominently Sonny Rollins, Abbey Lincoln, Benny Golson, Dinah Washington and Dizzy Gillespie. On Piano, Kelly returned to his personalized version of the Bud Powell lick to open his solo on the tune ‘Action’. This time, he adds to his chromatic tail with a mordant (D-Db-D) leading down to the root.

The recording of Buzzy was likely an awkward situation for Bud Powell; whatever the reason Powell had missed Parker’s first session, it was the first time Parker got to test out his erratic bandmate in the isolated environment of the recording studio. In a similar way, the recording of Miles Davis’ now classic Kind of Blue in March and April of 1959 may have been awkward for Wynton Kelly. Davis had hired Kelly in 1958, prior to the recording of Kind of Blue, and continued to use Kelly in live concerts through the early 1960s, as well as on the album Someday My Prince Will Come. As Ashley Kahn writes, when Kind of Blue was recorded, ‘despite having hired Wynton Kelly to take over the piano spot[in his band]…Davis called [Bill] Evans and set up studio time at Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio.’ In Miles: The Autobiography, Davis writes that ‘ Wynton joined us just before I was going into the studio to make Kind of Blue, but I had already planned that album around the piano playing of Bill Evans, who had agreed to play on it with us.’

A more magnanimous bandleader might have have been motivated to bring Kelly in on one tune of the album at least partly to appease hurt feelings. Davis, however, was famously single-minded and unsentimental in his musical decisions. According to Cannonball Adderley, he fired pianist Red Garland, with whom he recorded five of his most influential albums, and hired Kelly when he happened to be in the audience at a gig for which Garland was late. So it is more likely that his reasons for having Kelly on ‘Freddie Freeloader’ were purely musical. The form and style of the tune – straight-ahead jazz blues – is one that Evans avoided throughout his solo career, and one at which Kelly excelled and which he chose often on his solo records. Davis was quoted as saying, ‘Wynton Kelly is the only pianist who could make that tune get off the ground.’

In the second chorus of his Freddie Freeloader solo, Kelly finds yet another variation on the lick that had started out as an echo of Bud Powell’s phrase. In this permutation, he gives the phrase a different ‘head’, replacing the opening triplet with a three-note ascent (Bb-Db-D). He also alters the ‘tail’ he had added to Powell’s lick through the use of a phrase common in Charlie Parker’s solos, identified as the ‘four lick’ by Barry Harris (F-Eb-C-Db-D natural.) This alteration of both ends of the phrase is one reason I would say the Freddie Freeloader solo marks the ‘innovation’ stage in Kelly’s use of Powell’s lick; another way that Kelly innovates is in the way that he begins the lick on a ‘weak’ beat (beat two). In all his other uses of the lick, Kelly makes the main accent of the phrase fall on a strong beat. Moving the lick to beat two, as well as compressing it into sixteenth notes, allows Kelly to fit the lick into a ‘hand to hand conversation’ phrase where the strong beat is occupied by the left hand ‘chord question’.

In my view, it is not a coincidence that the last solo in this chronological sequence is also the one in which Kelly employs the ‘hand to hand conversation’ strategy most clearly. In a future blog post, I will discuss how Kelly went on to develop the conversational strategy in his improvising as a problem-solving technique for tunes where composers including John Coltrane and Wayne Shorter presented him with the challenge of improvising on unfamiliar chord progressions.

(I used the Bud Powell Discography and Wynton Kelly Discography at jazzdisco.org as references for this post.)